How Native American Communities Are Addressing Climate Change

34:19 minutes

This story is part of Degrees Of Change, a series that explores the problem of climate change and how we as a planet are adapting to it. Tell us how you or your community are responding to climate change here.

This story is part of Degrees Of Change, a series that explores the problem of climate change and how we as a planet are adapting to it. Tell us how you or your community are responding to climate change here.

Indigenous peoples are one of the most vulnerable communities when it comes to the effects of climate change. This is due to a mix of cultural, economic, policy and historical factors. Some Native American tribal governments and councils have put together their own climate risk assessment plans. Native American communities are very diverse—and the challenges and adaptations are just as varied. Professor Kyle Whyte, a tribal member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, says that many of the species and food resources that are affected by climate change are also important cultural pieces, which are integral to the identity and cohesion of tribes. Explore the interactive map of Indigenous people’s resilience action plans below.

“We’re salmon people… That’s how we survive.” — Ryan Reed, Karuk And Yurok Tribe

Some of these plans are incorporating tribal knowledge with management strategies. Ryan Reed, Spring Salmon Ceremonial Priest of the Karuk People, Hoopa Valley tribal member and descendant and Yurok tribe descendant describes the changes he’s observed to salmon in his community. He tells SciFri before Friday’s interview:

“We’re salmon people. That’s our main staple. That’s how we survive. Salmon’s our relation. Growing up, my dad was a traditional dip net fisherman. I grew up at the fishery doing these traditional things that not very many people still say they can do or they have in their culture. And we caught up to 100 fish a day when I was younger.

I remember as a kid seeing all these fish coming in and out and seeing all these hardworking young men and men packing these fish out to give to elders, give to the rest of the community because that’s our only fishery. We only have one fishery that is legally given to us.

Within the last five years, we’ve probably caught maybe a hundred. That’s a direct observation that I’ve had personally, where a lack of fish are coming in. That’s just the frontline of everyday life. I don’t have to look into any science book to understand what is exactly going on around me.”

Located in the Pacific Northwest, the Karuk’s climate adaptation plan addresses managing the landscape with traditional burning practices. Previously, this practice had been outlawed by federal and state authorities. The Karuk are now working with the Forest Service allowing the tribe to burn and manage nearly 6,000 acres of their land.

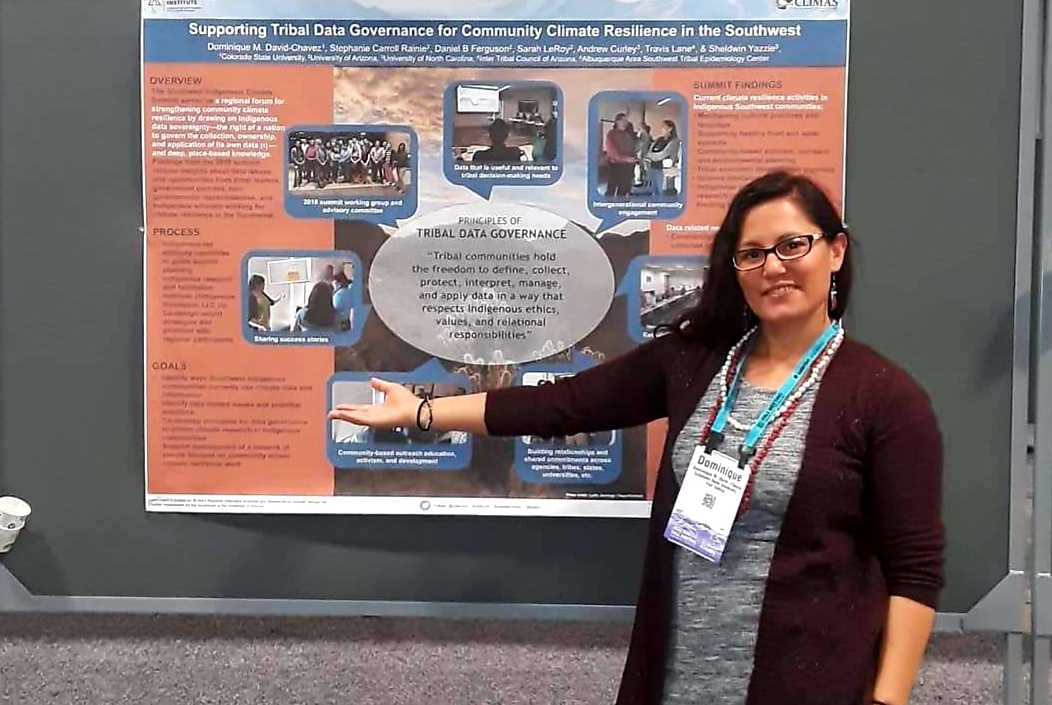

“It’s important to recognize that our communities have been adapting to climate for a long time.” — Dominique M. David-Chavez, The Caribbean Arawak Taíno

Dominique M. David-Chavez, a research scientist and descendant of the Caribbean Arawak Taíno, talks about the architecture and planting practices of Caribbean Indigenous communities used in scientific observation and innovation. Before Friday’s broadcast she says:

“Our Indigenous architectural practices really reflected where to orient your home, what direction in terms of wind, and what types of materials to gather, what type of year to gather those materials, to the point where people were observing that some of the structures that had used Indigenous architectural techniques were stronger withstanding the hurricane force winds, such as in Dominica, and I heard this on other island and Caribbean land-based communities as well.

We saw something similar in terms of planting practices—in terms of what food, what crops—were really resilient when they were experiencing extreme drought, extreme precipitation, hurricane force winds. I think it’s important to recognize that our communities have been adapting to climate for a long time—that we have sciences and technologies that reflect that, and that it’s so important that we value them, and continue learning about them and passing them down to this next generation.”

In Southeast Alaska, the Tlingit and Haida tribe is experiencing die offs of culturally significant trees due to low snowfall and paralytic shellfish poisoning of unknown origin. Raymond Paddock, environmental coordinator and member of the tribe, is working with community members to put together a climate plan to help monitor and mitigate these changes.

However, not every tribe has a climate plan—a lack of resources and tribal recognition can all be factors. James Rattling Leaf of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe is working on creating geospatial tools that would allow tribes to have better data and assessments, and eventually lead to more funding for climate plans and projects. As the Tribal Engagement Leader for the North Central Climate Adaptation Science Center, he also works with Great Plains tribes that are facing water issues—including drought, flooding and pollution.

Rattling Leaf says that the increased use of these practices are a reflection of entering the “decade of traditional knowledge.”

“I’m finding the interest is [in] traditional knowledge, how have Indigenous people dealt with a changing world and a changing environment,” Rattling Leaf tells SciFri over the phone. “Then you add resilience into that—how do we build resilience using our traditional knowledge.”

Transcripts have been edited for clarity and length.

*Editor’s Note 2/11/2020: On Feb. 7, 2020, the title for Ryan Reed was incorrectly stated on this page and during the live broadcast. We have updated the text with his correct affiliation. We regret the error.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Kyle Whyte is a tribal member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation. He’s also a professor and Timnick Chair of Philosophy and Community Sustainability at Michigan State University in East Lansing, Michigan.

Ryan Reed is a tribal member of the Karuk and Yurok Tribe, and a sophomore undergrad student in Environmental Science at the University of Oregon in Eugene, Oregon.

James Rattling Leaf is a tribal member of the Rosebud Sioux, and Tribal Engagement Leader for the Great Plains Water Alliance. He’s based at the North Central Climate Adaptation Science Center at the University of Colorado, Boulder in Boulder, Colorado.

IRA FLATOW: This is “Science Friday.” I’m Ira Flatow. Continuing with our Degrees of Change series, some of the communities most vulnerable to impacts of climate change are Indigenous people for historical economic, political, and cultural reasons.

This fall at the Society for Advancement of Chicanos, Hispanics, and Native Americans in Science, SciFri producer Christie Taylor talk to Hilda Heine, the President of the Marshall Islands.

HILDA HEINE: We depend on the land. Many of the activities that are part of our culture, they do emanate from our activities on the land. And so without that, the culture is going to be lost.

Everyone in the Marshall Islands has a connection to a piece of land in the Marshall Islands. That’s their home. And so without that, it’s like, what are we? We don’t have a home to come to.

IRA FLATOW: She was talking about– Hilda Heine, President of the Marshall Islands talking about a recently declared climate crisis due to rising sea levels. And that is threatening to wipe out a lot of nations with low sea levels, a lot of island nations. And in this episode of degrees of change, we’re focusing on the effects of climate change on the Indigenous people here in the United States.

Native American communities are very diverse, and so are the climate issues they’re facing and their plans for environmental changes. Tribes are putting together their own climate plans and risk assessments. The good news is that they have many years of experience dealing with nature.

So how do tribal knowledge– how does tribal knowledge play a part in the plans? We’re going to take a look at what is happening in a couple of Native American communities. So let me please introduce my guest.

Kyle Whyte is a professor and Tim Nick chair of philosophy and community sustainability at Michigan State University in East Lansing. He’s a tribal member of the Citizens Potawatomi Nation. Welcome to “Science Friday.”

KYLE WHYTE: Nice to chat with you, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: Pottawatomie– sorry for getting that wrong. Ryan Reed is an undergrad student, environmental studies at the University of Oregon in Eugene. He’s a cultural practitioner of the Karuk tribe, a spring salmon ceremonial priest of the Hoopa tribe and Hoopa tribal member and Uruk descendant. Welcome to “Science Friday.”

RYAN REED: Thanks for having me.

IRA FLATOW: And we want to know from you our listeners. Are you a tribal member? Tell us what climate issues and adaptations your community is facing.

Give us a call. Our number– 844-724-8255. That’s 844-SCI-TALK. Or you can tweet us @scifri.

Well, let me begin with you, Kyle. You said that for Native American communities, climate change and adaptation is not a new issue. What do you mean by that?

KYLE WHYTE: Well, if you took a class in college that featured Native American history and our oldest traditions of political philosophy, one thing you’d find out is that going back to time immemorial, going back many generations, we designed our societies specifically to be adaptive to a constantly changing environment around us.

IRA FLATOW: And so you are always ready for some sort of climate change?

KYLE WHYTE: We do our best to be, but you know, the idea of having to be ready and thinking about both seasonal change but also, you know, change across different eras– so like, climate change was a core part of our ceremonies, our cultures, our political life. And so we’re always thinking about what does it mean to adapt. What does it mean to be resilient? What does it mean to adjust to change in the best ways possible for everybody?

IRA FLATOW: So tell me why Indigenous and Native American communities are especially vulnerable.

KYLE WHYTE: Well, one of the key reasons is that often times, due to decisions that were made against us, our communities are situated in small locations, in reservations, in jurisdictions that aren’t very big. And so we don’t have a lot of room to move around.

And so a change like coastal erosion or a change in water temperature, we don’t have a lot of options to adapt in such small territories. And this is not how our ancestors lived. They lived in large regions where they were constantly moving. And so colonialism as we experienced by the US shrunk our territories and imposed boundaries on us that are not very good from the standpoint of being adaptive.

IRA FLATOW: Tell me what you mean by that.

KYLE WHYTE: Well, for example, if your ancestors were living in an area that was the size of three or four states in the United States but now you live in an area that is a fraction of that size, even a fraction of just one of those states, then that means that you really can only relate to plants and animals and insects and to ecosystems within that very small area. And so what if the habitats in that area are ones that change and the plants or the animals that you care about are ones you can only relate to if you move off that reservation and engage with them in another location? But if the law says that you don’t have the same rights to harvest or celebrate those plants and animals off reservation, then you can’t be able to continue those traditions and practices.

IRA FLATOW: So how long– so you’re saying then you have to adapt to something new. And how long– and what does that mean?

KYLE WHYTE: Well, you know, it means actually having to negotiate some extremely challenging political issues– for example, tribes that are having to consider resettlement due to coastal erosion. They’re having to realize that they might need to move to a new location and that they have to go through a nightmare of bureaucratic obstacles at the county level, the state level, the federal level. Whereas, a long time ago, their ancestors who were able to move throughout those regions would have been able to situate themselves with much, much more ease.

IRA FLATOW: There are native communities putting together their own climate adaptation plans using traditional knowledge systems. How do you put these plans together, Kyle?

KYLE WHYTE: So I’ve worked with a number of tribes on their climate change adaptation plans and just on their environmental planning in general. And it’s a community process. One of the things that Indigenous people are taking leadership in is the idea that if you’re going to have a plan for how a community is going to prepare for climate change, it has to be a plan in which all generations, from children to elders, are involved at the grassroots level.

It has to be one that motivates people based on the idea that our traditional practices matter to us. And we have a longstanding history of being people who were very acutely aware of how to respond to climate change and to seasonal change, and that the climate change plans also have to be political. Our tribal councils and our intertribal organizations have to endorse them and have to take them to Washington, have to take them to other political centers of power so that we can have the adaptive capacity that we need.

IRA FLATOW: That’s interesting. Ryan Reed, the Karuk tribe is in the Pacific Northwest. What environmental changes have you observed where you live and describe where you live and what’s going on there.

RYAN REED: Yeah. So, well, our ancestral territory is northern California like right at the border. Actually, a little bit of our ancestral territory cedes into Oregon. And so I guess like just growing up and, you know, firsthand experiences, salmon is our main staple of food.

You know, that’s what feeds our people. That’s what connects us to the relationship of salmon into our culture. And just the small period or time I’ve been on this earth, we have had tremendous population drops in salmon.

You know, it went from as a child catching up to 100 fish a day, and now we’re catching up to less than single digits in one year. And so that’s probably one of the biggest changes I’ve seen as a first-hand experience in addition to catastrophic, high intensity wildfire. And I think those are just the two things that are like really penetrating our culture and really creating a big disparity within our social being.

IRA FLATOW: So you, the Karuk, have adopted a very detailed climate plan, I understand. And you mentioned these wildfires. They involve prescribed burns, do they?

RYAN REED: Yeah, so fire is a special tool. It’s a giver and taker of life for us. And so we used fire before contact, before colonialism started to hit our people, as a tool to adapt to the climate change because climate change is something that’s new. It’s not just a one single process event. And so we use fire as a tool to really battle those climate change and different weather patterns that occurred over geological time. And so prescribed burn fire today has been really significant and to really decolonizing and revitalizing our culture and our resources around us that we need to survive.

IRA FLATOW: Our number 844-724-8255. We’re asking you to call in and talk about it. Let’s go to Justin in Baja, California. Hi, Justin.

JUSTIN: Hey. How’s it going? [INAUDIBLE].

IRA FLATOW: Hi there. Go ahead.

JUSTIN: Yeah, so my tribe, the Cocopah, we’re in the Sonoran Desert in Baja California and Sonora. And then there’s also a community up in Summerton, Arizona. And we’re facing a variety of climate challenges from the drying up of the river changing our fishing, our traditional fishing at El Mayor being forced more and more into the ocean. The river doesn’t reach the ocean anymore. We’re having hurricanes and things like that happening with the warmer waters that we don’t normally experience and high intensity wildfires wiping out our cottonwoods and our salt feeders. And so all of these along with the fact that we’re a river and ocean tribe, the rise of sea level is all a big concern for us.

IRA FLATOW: Do you have an adaptation plan, Justin, in place in your tribe?

JUSTIN: It’s something that we’re working on. Because we’re a binational tribe, the folks that– we’re down here in Mexico. We’re talking about things like what happens if the sea level rises, how can we move. Of course, the Mexican government makes that a little bit more challenging, and the fact that the United States border is there also makes disaster response and planning across the border more challenging.

IRA FLATOW: That’s great. Thank you for calling in. Kyle, not all tribes have climate plans. Our caller said they were trying to develop one. Why do they not have them yet?

KYLE WHYTE: Well, I first wanted to note that in the National Climate Assessment that came out last year, there is a tribal chapter that shows almost 800 different tribally-led climate change initiatives. So on the one hand, there’s many tribes that have been doing this and taking leadership on this. But on the other hand, a lot of us are working really hard to find ways for every tribe to be able to plan for climate change.

But one of the key challenges is that a lot of Indigenous people, a lot of tribal nations, we’re really trying to rebuild our governments, and we’re trying to create capacities to have those climate change plans. And so a lot of times, the funding that would support a climate change plan either isn’t available or it’s not enough. Or it’s not sufficiently sensitive to the types of employment situations that many tribes face.

IRA FLATOW: Ryan, you are all working with the Forestry Service on the plan. How does that work?

RYAN REED: You know, it’s a very difficult process just considering our historical background and our historical relationship with the Forest Service. It’s very violent and very dehumanizing. You know, we were bounded to not set our cultural fires on our landscape.

And we actually had a $5 scalp bounty on our backs for that. And so to really revitalize that relationship and good terms, it’s been a long process. But I think now that we have this climate change adaptation plan, it really gives us some support and really leverage to really significantly show that we know what we’re talking about in a Western science context, which is very significant in today’s day and age.

IRA FLATOW: I’m Ira Flatow. This is “”Science Friday” from WNYC Studios. Let me ask both of you.

Individual tribes are working on their own climate action plans, and they’re working with scientists who have a Western view of science. What kinds of conversations or actions would you want to see to protect tribal knowledge in this process? Kyle?

KYLE WHYTE: One of the key conversations that needs to happen is that our traditional knowledge has a lot of elements that are private to it, that are intimate to our communities. But it also says certain things about the land and our relationships to the land that can oftentimes be exploited by others who might not know certain things about where certain fish are or where certain plants are. And so scientists really need to approach their relationship with us not from the standpoint of how can they get as much out of us, but rather, how can they cooperate so that both parties achieve their goals?

IRA FLATOW: And Ryan, what do you say to that?

RYAN REED: Yeah, I really like that point that he made. In a way, it’s not really our duty to do so, you know? We should have that mutual respect from Western science, to really have that acknowledgment of our sacredness in our culture. But also, in addition to that, I think just having tribal members or tribal people of that land who grew up in that land and knows the ins and outs of that land to be there on the front lines helping restore and rebuild our environment.

IRA FLATOW: You know, I remember we do we did a story recently about the sensitivity of scientists wanting to build a telescope on the top of Hawaiian mountain that was sacred to native Hawaiian tribes. And they went through a long conversation. And finally, I think the government conceded that the native Hawaiians had a point to be made over there. Do you sort of see this as a different battle sort of in the same spotlight here of trying to make scientists aware of what your cultural sensitivities are?

KYLE WHYTE: Well, I’ve trained many hundreds of climate scientists in best practices of how to work with tribes, and one thing I’ve emphasized is that even though there are oftentimes compelling curiosities and questions that Western scientists are asking, sometimes there’s a tendency to forget that our stories as native people not only have those compelling empirical and scientific questions too, but also, we’re part of an extremely compelling story of rebuilding our nations and rebuilding our cultures and societies and achieving success and sustainability in the future. I think sometimes, scientists need to realize that that’s perhaps a greater goal to be part of. And that means they have to respect our interests, our needs, and what’s sacred and private to us.

IRA FLATOW: We heard from the president of the Marshall Islands early. There are many Indigenous communities globally facing similar issues and younger Indigenous activists. How does that make you feel, Ryan? Hopeful?

RYAN REED: Of course. You know, from what I’ve– my narrative has been building over and over, and I think the base of that is just starting with our youth. You know, they’re the next leaders of our generation.

And so to have them influenced by the [INAUDIBLE] being very aware of these issues that are occurring on their homeland and in places around them is very significant just because that sets us for the next generations. And that’s what a lot of culture is based on is the generations to follow. You know, that’s how we prepare. That’s why we do the things that we do is to really help the generations to follow.

IRA FLATOW: Well, it really looks like the younger generation is taking the lead in environmental consciousness and hopefully in your tribes as well. I want to thank both of you.

Kyle Whyte, professor and Tim Nick chair of philosophy and community sustainability, Michigan State University in East Lansing, a tribal member of the citizens Pottawatomie nation. Ryan Reed, undergrad student in environmental studies university of Oregon in Eugene, tribal member of the Hoopa Valley tribal member and part of the Karuk and Uruk tribes. Thank you both for taking time to be with us today.

RYAN REED: Appreciate.

KYLE WHYTE: Thank you.

IRA FLATOW: You’re welcome. We’re going to take a break, and we’re going to come back and talk more about climate change issues and adaptations in Native American communities. We’re going to go out to the Pacific Northwest a little bit and talk about what’s going on out there.

So stay with us. We’ll be right back after this break. This is “Science Friday.” I’m Ira Flatow.

Continuing our degrees of change series, talking this hour about climate change issues and adaptations in Native American communities. I want to bring on a guest who is looking at water issues in his tribal community. James Rattling Leaf is a tribal member of the Rosebud Sioux, tribal engagement leader at the North Central Climate Adaptation Science Center at the University of Colorado in Boulder. He’s joining us from Rapid City, South Dakota. Welcome to “Science Friday.”

JAMES RATTLING LEAF: Good afternoon, Ira. Let me begin by introducing myself in my Lakota language. [SPEAKING LAKOTA]

IRA FLATOW: Well, thank you for that. We’re approaching our 30th year on “Science Friday” and we’ve never had anyone introduce themselves in their native language. So it’s a good way to begin.

I want to just tell our listeners also is– are you a tribal member? We want to hear from you. Tell us what climate issues and adaptations your community is facing. Our number is 844-724-8255, 844-724-8255.

You can also tweet us @scifri, and we do have some phone calls coming in. James, you’re a member of the, as I say, the Rosebud Sioux. Describe the community for us please.

JAMES RATTLING LEAF: Yes, Ira. We’re in the North Central Great Plains and South Central South Dakota. And my tribe, the Rosebud Sioux tribe, is also part of a greater alliance called the Oceti Sakowin, or also known as the Great Sioux Nation.

And so we’re in the Great Plains, grasslands, primarily an agricultural tribe, a lot of grazing and farming and those sort of sectors. You know, we face extreme events in this part of the country in terms of weather and climate patterns. But we’re still here. We’re also called a Buffalo people, the Tatanka or Buffalo people. And so we have a long history, a long memory of the land here in this part of the country.

IRA FLATOW: You’re part of the Great Plains Water Alliance, which includes several different tribes tell us what the climate issue changes are that you’re facing. What challenges are there?

JAMES RATTLING LEAF: Well, certainly to talk about current realities for us is we just went through a series of spring floods this past year. And the current outlook is we’re going to have those floods again. And so as I mentioned, extreme event seems to be the future for us here. And so flooding and the impacts of flooding have really impacted two tribes in particular– the Rosebud as well as a Pine Ridge Sioux tribe.

And so tribes now have to deal with cleanup, have to deal with infrastructure issues in terms of delivering clean water to the communities. And so it’s a tremendous challenge to our tribes here. And so obviously, they’re seeking resources and funding to address those issues. But certainly, we’ve got a long ways to go.

IRA FLATOW: When you say you’re seeking resources and funding, who do you try to get them from? The federal government, or whom?

JAMES RATTLING LEAF: Yes, Ira. As you know, American Indian tribes have a unique federal issue with the government. And so we do those through treaties– 1851 and 1863. And in those treaties, they are the supreme law of the land.

And so we have this relationship with the federal government. And in that relationship, we work with the fellow government to do programs, to do projects, to help support infrastructure– in particular, water. So we have one of the largest world water systems in the world in our part of the country–

IRA FLATOW: Wow.

JAMES RATTLING LEAF: –called [INAUDIBLE]. And so that delivers clean water from the Missouri River as well as the Ogallala Aquifer. And so that took a tremendous amount of funding from the federal government to do that work. But also interesting to know that also, our non-tribal neighbors and counties in South Dakota also benefited from that water line.

So that project brought many entities together. And again, it was through federal funding that made those things happen. So we continue to advocate strongly for those agreements and those promises the federal government made to us when we ceded land way back in a day. So we continue to advocate strongly for our treaties, the implementation of treaties, those things like education, health care, and obviously water and those important aspects for nations, continue to do that today.

IRA FLATOW: And now I know the Great Plains also includes the Standing Rock tribe, where the Dakota Access Pipeline is. How does that action fit into all of this?

JAMES RATTLING LEAF: Well, thank you for sharing that. I know that was a global event. And really, I think, for the first time again, it brought awareness to the world about our issues from our part of our country.

And so we had a term. We had a rallying cry called mni wiconi. It means water is life.

And so the Standing Rock took the first action to make a stand, to make a declaration saying that these pipelines are harmful to the land, harmful to the water, harmful to our people. And so they took action. And they brought people together through prayer and ceremony that guided the people, guided the partners that came and supported the effort. So again, it was a tremendous global event to bring awareness to the issues that we still face as tribes. But also, I think it created a sense of energy, a visioning process, to think about where do we go from here and what are the things that we need to do to prepare for a changing climate but also all the other aspects of what it takes to manage our land and our resources.

IRA FLATOW: OK, I want to go to the phones. Let’s go to an elder from the Gila River Community. Hi. Welcome to “Science Friday.”

SPEAKER 1: Good gosh. Hello.

IRA FLATOW: Hey there. Go ahead.

SPEAKER 1: I am an elder in my 80s from Gila River Indian community in South Central Arizona. We’re midway between Phoenix and Tucson. And we are primarily– we live in the desert, but we originally were a farming agricultural community. And we lived off the Gila River.

In fact, our tribal name, [INAUDIBLE], is River People. We call ourselves river people because we lived and sustained for centuries off a complex system of irrigation canals under the city of Phoenix and the entire metropolitan area until our water was stolen from us by upstream non-Indian farmers. And it decimated our people and our agrarian and healthy way of life, almost extinguishing us until we fought for many, many years to get our water back.

And we won the largest water rights settlement in 2004. And since that time, our tribe has been on a path to rebuild our agricultural economy and to teach our people to return to the values of living off the land and growing our own food and living a healthy lifestyle. And unfortunately, climate change has contributed– now that we’ve got our downstream water back and we won it through the water rights settlement, we are affected by climate change by the decline in runoff from the thawing upstream.

But two things that your two first young people spoke to I would like to address as very good points– the first thing was adaptation. Yes, we have always adapted. That is the primary unique characteristic of Native American people.

And you can adapt within your reservation environment. But in our case and in most cases, the reservation lands that we were put on have limited resources. Ours had a river.

And when that was stolen, that stole our whole way of life. Now we were rebuilding, and our tribe is really in the forefront of rebuilding a way of life through conservation and using water sparingly. And education, of course, is the key. And one of the things that we have done is as a tribe is to integrate a conservation curriculum into our reservation schools. And one of the most notable things that has been by our tribal leaders is to develop the first ever long-term water plan for how to use the water that we have won through the courts and through the Congress, use it and conserve it.

IRA FLATOW: Well, thank you very–

SPEAKER 1: And part of that–

IRA FLATOW: Thank you very–

SPEAKER 1: I want to mention–

IRA FLATOW: OK, quickly.

SPEAKER 1: [INAUDIBLE] was partnership with the state of Arizona, city of Phoenix, to develop what is called the drought contingency plan, which is really a partnership between Arizona and Nevada and Colorado to preserve the water in the Colorado River. And our tribe has had the foresight to enter into partnerships with surrounding communities, non-Indian communities as well as Indian communities, and to promote education and awareness among our youth.

IRA FLATOW: I’m glad you dropped that last bit in. Thank you. Thank you for educating us on that. James, you know, it looks like Native Americans have a lot to teach white people about how to deal with this, with climate change.

JAMES RATTLING LEAF: Well, I just want to thank the caller and the input and her thoughts. I know– I’m somewhat aware of that work in Arizona and the importance of water adaptation planning and policy. I think in the discussion before, the role of traditional knowledge came up.

And that’s a term that UN is using now– traditional knowledge. And so I’ll use that today. I think it can be applied in many different ways.

I’ll share a little story. I was invited to Australia two months ago to be a part of the delegation of America with NASA, USGS, and NOAA to be part of something called the Global Earth Observations Meeting. And in that meeting, we had the first time ever an Indigenous effort, Indigenous focus, to look at bringing all Indigenous people together to talk about our issues.

And so I had a chance, an opportunity, to meet with other Indigenous people from all the continents. And we sat together around the table talking about what do we need to do. And one of the things that we emphasized, and I think this is reflective of traditional knowledge, is that we have a responsibility.

I think we as Indigenous understand that we have a responsibility to this earth. And through our life ways, through our ceremonies, and through our spirituality, we practice that every day. And we wanted the scientific community to know that.

The second part is that we understand that we need to do something called intergenerational knowledge transfer, that we need as older people and the elder that called in, we need to be the past at that knowledge on, that wisdom on, to our youth. That’s also important.

And finally, we also agreed that partnerships are important. And so we wanted to really consider and reflect deeply how science and technology can help us, work with us, and advance our people. And so we’re critically reflecting, taking a deeper dive into the role of science, technology, and how that can support our vision.

So that’s exciting because that tells me that Indigenous people around the world want to work together, and we’re developing a platform for that. So I appreciate the partners that brought us together. And we’re going to continue that work. And that global work is important because we can learn from each other in terms of how we apply traditional knowledge. And that’s the exciting part is technology could bring us together to do that.

IRA FLATOW: Interesting point. I’m Ira Flatow. This is “Science Friday” from WNYC Studios talking with James Rattling Leaf of the Rosebud Sioux. So what you’re saying is you are adapting– you are melding in your cultural history with NASA-like technology to come up with–

JAMES RATTLING LEAF: That’s right.

IRA FLATOW: –ideas.

JAMES RATTLING LEAF: Yeah, that’s right. I mean, I think–

IRA FLATOW: Tell us about the Native View plan that you’re working with.

JAMES RATTLING LEAF: If you look at it– so I’m greeting you from the Black Hills of South Dakota, the geographic center of North America. And it’s a sacred place to our people. And I’ve seen maps drawn by elders who looked at the Black Hills, and because of the significance of that.

And then you look at a satellite image from NASA, and you see how closely those geographic features represent. It’s amazing. And so we know through our oral history that we have this understanding, that we looked at the Earth from above.

I think elders that tell us that we need to connect spiritually and physically between the skies and the earth is wisdom. And that’s traditional knowledge. What happens above happens below.

What happens below happens above. Those kind of things, those kind of philosophy, those kind of wisdom, is what’s before us. And so NASA is very interested and other partners interested in these kind of discussions and dialogues.

So I can see, Ira. I can see in a future where we’ll have these dialogues where we bring our spiritual people together. We bring our NASA scientists together around the table have these deep discussions on what does it mean for the future.

IRA FLATOW: It’s great. That’s great. James, thank you so much for sharing this with us. It’s quite enlightening. James Rattling Leaf is a tribal member of the Rosebud Sioux, tribal engagement leader at the North Central Climate Adaptation Science Center, University of Colorado in Boulder. Thank you again for taking time to be with us today.

JAMES RATTLING LEAF: Well, thank you, Ira. And I guess, again, to your listeners, I encourage them to join us. Remember, the Lakota word means allies. And so we seek those allies that we work to advance our people, our nations, but also our country. So thank you very much, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: You’re welcome.

JAMES RATTLING LEAF: [SPEAKING LAKOTA]. Thank you all very much.

IRA FLATOW: And you can read more and listen to more interviews at our website at sciencefriday.com. You can add some more to our interviews with Hilde Heine, the president of the Marshall Islands, about what her country and community is doing in the face of climate change. It’s going to drop in the “Science Frida podcast next week.

So make sure you subscribe one last thing before we go– we’ve been exploring the Great Lakes with our book club this winter reading Dan Egan’s The Death and Life of the Great Lakes next week, we’re going to be wrapping it up. But in the meantime, producer Christie Taylor is here with a couple of reminders. Hi, Christie.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Hey, yeah. So as you mentioned, we have gone all over the place with the “Science Friday” book club to the Great Lakes and the eight states from New York to Minnesota that touch them. We’ve learned about the connection between invasive mussels and toxic algae blooms, why clear water can actually be bad, and how native fish and biodiversity can make an ecosystem more resilient to the forces of change.

IRA FLATOW: I love what we’re doing. What’s next? What are we having another– we’re having another chat next week, right?

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Right. Well, and you know, we’re going to take some of your memories. We want to hear your memories of the Great Lakes and how they’ve touched you.

And we are also going to bring it all together into a conversation, same bat time, same bat channel, with some science nerds. In the meantime, we want to hear your thoughts and comments on our SciFri VoxPop app. What did you learn? What are your questions about the future of the Great Lakes or water health as a whole?

We want to hear your voice memos. And then our New York listeners can come to the book club in person later this month. We’re having a roundtable about New York City waterways and how they’re being restored– good news if you’ve been depressed about invasive species lately– and bringing author Dan Egan in to grill him about what’s happened in the Great Lakes since he wrote his book. You can find all this and more on our website sciencefriday.com/bookclub.

IRA FLATOW: Looking forward to that, Christie.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Thank you.

IRA FLATOW: SciFri book club producer Christie Taylor.

Copyright © 2020 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Alexa Lim was a senior producer for Science Friday. Her favorite stories involve space, sound, and strange animal discoveries.

Lauren J. Young was Science Friday’s digital producer. When she’s not shelving books as a library assistant, she’s adding to her impressive Pez dispenser collection.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.