NASA Finally Opens Canister Containing Asteroid Sample

12:13 minutes

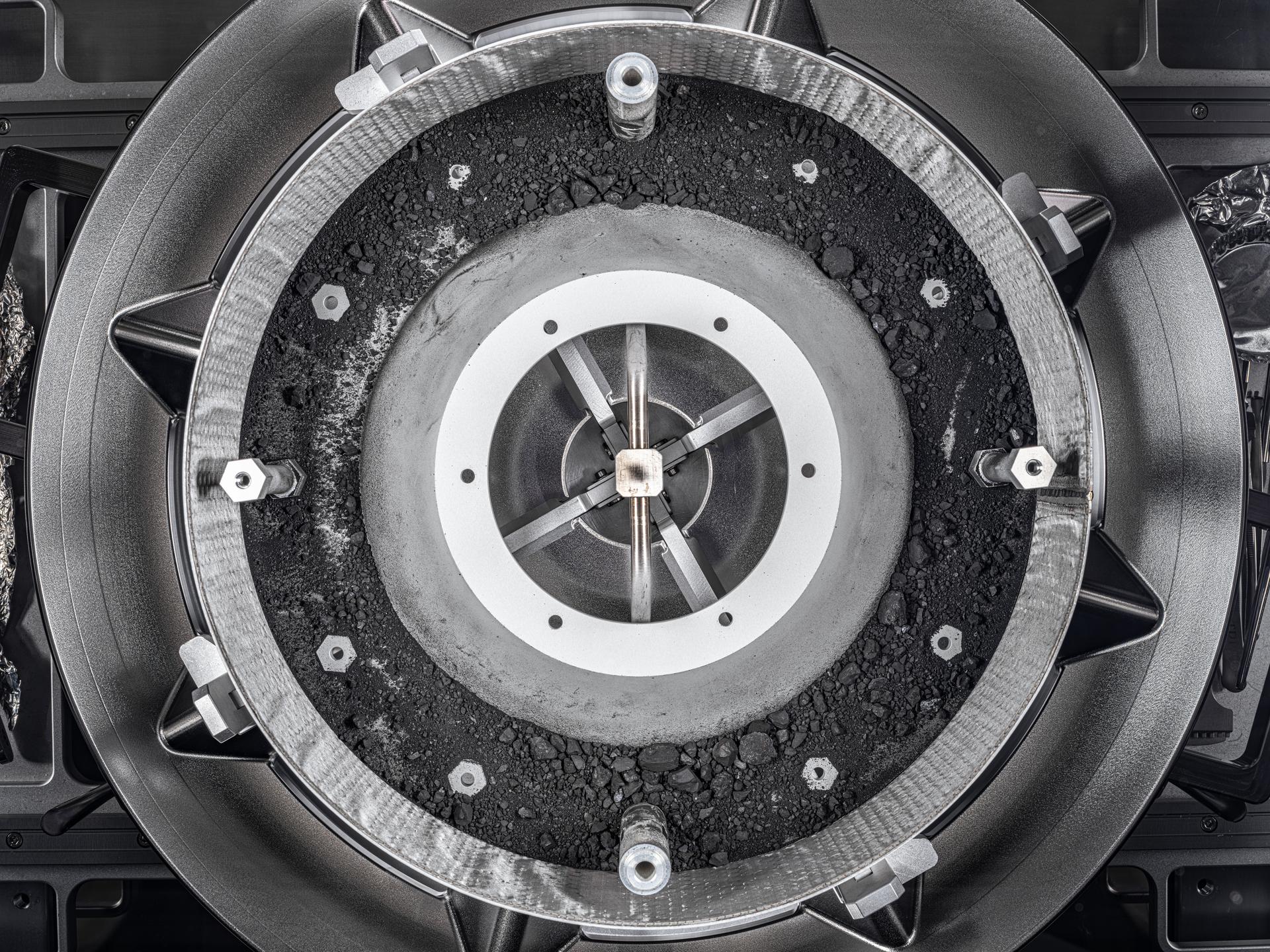

NASA’s OSIRIS-REx was the first U.S. mission to retrieve fragments of an asteroid, which arrived in September 2023. There was just one small issue: NASA technicians couldn’t open the capsule, which held space rocks from an asteroid called Bennu. NASA announced this week that they finally managed to open the capsule on January 10. Engineers designed new tools to remove the final two of 35 fasteners, which would not budge.

Guest host Arielle Duhaime-Ross talks with Maggie Koerth, science writer and editorial lead for Carbon Plan, about the asteroid capsule and other top science news of the week, including chimpanzees catching human colds, advances toward a cure for autoimmune disorders and honeybee crimes.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Maggie Koerth is a science journalist and a climate editor at CNN, based in Minneapolis.

ARIELLE DUHAIME-ROSS: This is Science Friday. I’m Arielle Duhaime-Ross.

You might know me from my work on the podcasts, A Show About Animals or Vice News Reports. I’m really excited to be filling in for Ira Flatow this week.

Later in the hour, we’ll look at the quote, unquote, mysterious dog illness making rounds across the country. Plus, inside the effort to make children’s television more accessible to deaf kids with an animated series in American Sign Language.

But first, NASA has announced the Mars helicopter Ingenuity has taken its last flight. The little helicopter first arrived on Mars in 2021, along with the Perseverance Rover, and since then has taken 72 flights– way longer than the planned 30-day mission, scoping out craters and riverbeds for signs of water on Mars’ surface.

But during a recent flight, the Rover lost communication with the helicopter as it was landing. And once communication was restored, images from the helicopter revealed rotor blade damage, meaning it’s now grounded permanently.

And now a bit more space news. This is an update from NASA’s OSIRIS-REx. Mission. It was the first US spacecraft to bring back fragments of an asteroid. The pieces arrived late last year, which is very cool. One small issue, though. NASA’s technicians couldn’t get the capsule open, you know, the very important one that holds the space rocks. But now they’ve done it.

Joining me to talk about that and other top science news of the week is my guest. Maggie Koerth is a science writer and editorial lead for Carbon Plan, based in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Maggie, thanks for joining us.

MAGGIE KOERTH: Yeah, thanks for having me back.

ARIELLE DUHAIME-ROSS: So, Maggie, please tell me, why couldn’t NASA open this capsule? And how did they finally break it open?

MAGGIE KOERTH: Well, think about this as one of those times you just really wanted a pickle and, for the life of you, you couldn’t get the lid off the jar. But in this case, the jar is a capsule sent back to Earth from space and the pickles are 4.5-billion-year-old rocks from the dawn of time.

ARIELLE DUHAIME-ROSS: Mmm, sounds tasty.

MAGGIE KOERTH: Ironically, that’s also how old some pickles in my fridge are.

The deal with this is that there were 35 fasteners that locked this thing closed. And when they went to open it up, two of them just wouldn’t open. So to get inside, the engineers at NASA actually had to design and build their own bespoke tools from scratch.

ARIELLE DUHAIME-ROSS: Wow. All right.

MAGGIE KOERTH: Yeah, they spent the last few months reinventing a can opener. And now they got into it. And they really think these things are worth the trouble, though, because we are talking about rocks that have a lot to teach us about the earliest days of our solar system. And there is a possibility that they might even contain some of the biological precursors of life that can teach us about how life evolved on planet Earth.

ARIELLE DUHAIME-ROSS: Right. So now I really have a sense for why they worked so hard to get in there. But what’s next for the OSIRIS-REx spacecraft?

MAGGIE KOERTH: Well, OSIRIS never came back down out of space. It just shot this little capsule off from orbit and then it was sent off on another mission. So after dropping this capsule from Bennu, this asteroid that it got these rocks from, the spacecraft was then steered off. And it’s headed towards a 2029 rendezvous with Apophis, which is a massive asteroid that is going to pass close enough to Earth that it could even be visible with the naked eye.

ARIELLE DUHAIME-ROSS: Forgive me for this. We’ll be keeping an eye on that.

[LAUGHTER]

OK. So back down to Earth for a story about humans giving chimpanzees colds. We often think about it the other way around, right, animals giving humans diseases. But what’s relatively mild for us can actually be pretty deadly for a chimp, right? So tell me what’s going on here, Maggie.

MAGGIE KOERTH: Well, basically, it’s that zoonosis risks work both ways. Things that are really mild and don’t bother animals can transmit over to us and become deadly, and that happens in vice versa, too. So for example, a minor human respiratory infection, just something you’d call a cold and take with you into the office, ended up killing 12% of the Ugandan chimpanzee community back in 2017.

Rachel Nuwer had a really fascinating piece in Nature last week, where she was looking at these reverse zoonoses, the threats that they pose, and what scientists are doing to save animals that are at risk. There are international guidelines, even, for how tourists are supposed to interact with chimpanzees and gorillas in the wild.

So for example, we are supposed to stay 7 meters away from the great apes. And we’re supposed to wear masks.

ARIELLE DUHAIME-ROSS: Both of those things sound familiar.

MAGGIE KOERTH: Yep, that does sound real, real familiar. It’s been really, really hard to get tourists and workers in these national parks to actually do the social distancing and the masking. And a 2020 study of tourist groups even found that nearly everyone included in the research had violated the distance guidelines.

ARIELLE DUHAIME-ROSS: Wow.

MAGGIE KOERTH: So there is just this challenging tangle of incentives that are happening. The animals need the national parks and the tourism that funds those parks in order to be protected. And the tourists want to be able to get up close and personal with these animals to want to go to the parks. And so you have these spaces where protecting the animals sometimes ends up feeling like you have to put them at risk in order to keep them protected. It’s very messy and it’s not a simple thing to solve.

One of the things, though, when I was reading this article that really stood out to me was the fact that there are some solutions that are really simple and also really frustrating. Most of the guides, it turns out, don’t have sick days built into their jobs. So even if they feel lousy, they have to come in to work. And simply giving them paid time off could actually end up protecting the creatures that they’re trying to take tourists to see.

ARIELLE DUHAIME-ROSS: Right. So what I’m hearing is that we need universal paid sick time once again.

MAGGIE KOERTH: Once again, yes. Yep, it all just kind of comes right back around, doesn’t it?

ARIELLE DUHAIME-ROSS: Yeah. Our next story is sort of the reverse. It’s one of those stories about how animals transmit diseases to humans. A new study traces the origins of multiple sclerosis to a genetic mutation that popped up thousands of years ago to protect humans against animal diseases. Tell me more.

MAGGIE KOERTH: Yeah. So this is really super interesting. It’s a study of DNA from 34,000-year-old human bones and comparing them to modern DNA and looking for how things have changed over time. And what the researchers were finding is that the genes linked to MS trace back to these nomadic people called the Yamnaya, who populated much of Northern Europe during the Bronze Age.

Now, the Yamnaya were herders and they lived with their goats and their sheep. And generally, this was a time period where more humans were living closer together and having more contact with farm animals. And what you were getting was a lot more diseases.

And for these people, genes that made a highly responsive immune system were really helpful. But now you get their descendants, in an era of modern sanitation, and those same defenses seem to have turned on us. This study really helps explain why Northern Europeans, these descendants of the Yamnaya, have the world’s highest prevalence for MS. It’s actually double that of even Southern Europe.

ARIELLE DUHAIME-ROSS: OK. Well, this comes at an interesting time, right, because MS has been in the news a lot more recently. There’s a new treatment approach for these types of diseases that actually seems to be pretty promising, and I’ve been hearing about it. Can you tell me how it works?

MAGGIE KOERTH: Yeah. So Cassandra Willyard has a story in Nature this week that’s looking at the hunt for treatments and possibly even cures. And they could affect MS, a lot of other autoimmune diseases.

So her story is looking at three teams of scientists, who are working on different versions of the same kind of similar idea, basically, taking the antigens that the immune system is attacking and using them as a exposure therapy. Basically, you’re convincing your malfunctioning immune system that this particular thing it’s being exposed to isn’t actually a danger and that the immune cells trained to hunt it can go ahead and just deactivate.

ARIELLE DUHAIME-ROSS: So is this sort of like allergy shots?

MAGGIE KOERTH: Kind of a little bit, yeah. So this is not a totally new concept. In the past, there have been attempts at it, but they’ve gotten mediocre results. And these new techniques, they’re still in really early stages, but they seem a lot more promising.

There’s three different things that Willyard profiled in her article. and they’re all really different from each other so I’m not going to try to explain each of them in detail. But what they all share is this ability to deal with the fact that a disease like MS isn’t just a reaction to one antigen. So depending on disease progression, there could be lots and lots of things that get the immune system worked up. And it was really hard to figure out how to train the body to tolerate all of them when you don’t even know what all of them are.

So these new techniques, each have found a different path to multi-antigen tolerance. So it’s like using one car to convince your dog that he doesn’t have to bark at any cars.

ARIELLE DUHAIME-ROSS: So how far along is this research? Has it actually been tested in humans yet?

MAGGIE KOERTH: Some of these techniques haven’t been tested on humans yet. One of them has been through a small safety trial and is starting to recruit for efficacy trials. But it seems like we’re at a point now where we could see the possibility of a solution to a problem that’s thousands of years in the making.

ARIELLE DUHAIME-ROSS: Let’s move on to a story that, well, has been generating a lot of buzz. It turns out that honeybees are pollen thieves. Who knew these little guys were so lacking in human morals, such criminals?

MAGGIE KOERTH: I know. It’s a hard world out there on the mean streets of the flower garden. This is behavior that has been documented in several places in the US. But for the first time, researchers have now documented international honeybee theft rings. They filmed honeybees stealing from bumblebees in Italy.

ARIELLE DUHAIME-ROSS: Oh.

MAGGIE KOERTH: And I don’t like to blame the victim, but the bumblebees make it easy. They carry this pollen attached to their little furry bodies. And they just aren’t very aggressive– particularly the males. They don’t fight back. They don’t try to stop what’s happening.

So as part of the study, the researchers followed bee behavior over three years at three different sites. And at two of the three, the honeybees were law-abiding members of society. It was just that one spot, where, year after year, it was like the insect equivalent of a dark alley.

So they were trying to figure out what made things different. And what they came up with is it’s probably the food options. At the theft site, the primary honeybee food flower was this thing called a woolly thistle. And the bees had really been struggling to get the pollen off of that particular plant. So the scientists’ hypothesis is that, when food is hard to come by, but potential theft victims are also plentiful, that is when honeybees turn to a life of crime.

ARIELLE DUHAIME-ROSS: Well, now we know. That’s all we’ve got for now. Thank you, Maggie, for being here.

MAGGIE KOERTH: Thank you so much for having me.

ARIELLE DUHAIME-ROSS: Maggie Koerth is the editorial lead for Carbon Plan and a science writer, based in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Copyright © 2023 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Shoshannah Buxbaum is a producer for Science Friday. She’s particularly drawn to stories about health, psychology, and the environment. She’s a proud New Jersey native and will happily share her opinions on why the state is deserving of a little more love.

Arielle Duhaime-Ross is freelance science journalist, artist, podcast, and TV host based in Portland, OR.