NASA Is Making Some Big Promises. But Can It Deliver?

6:50 minutes

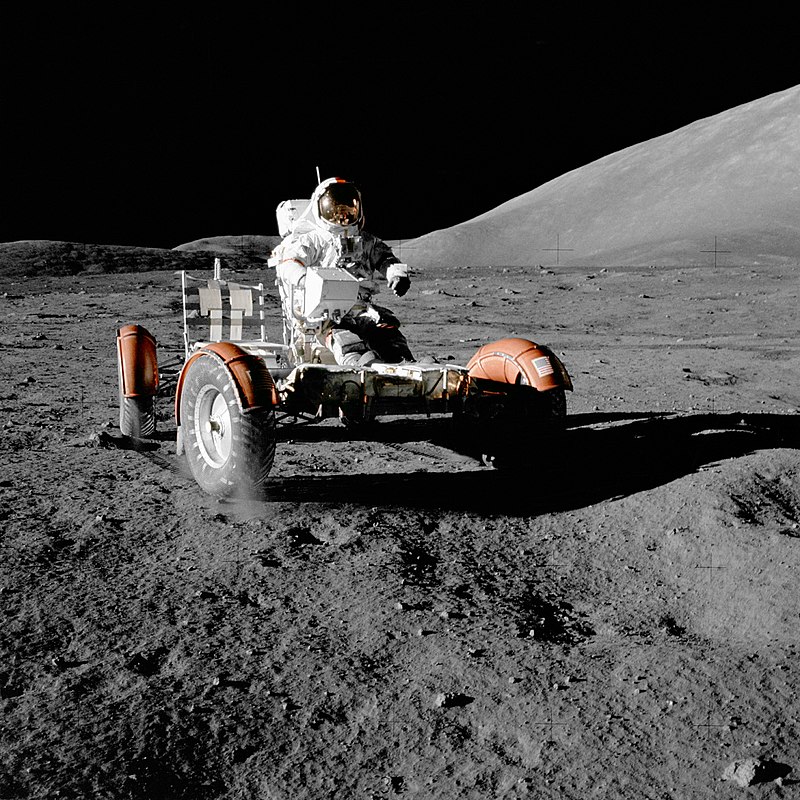

For those of us looking forward to one day returning to the moon, experts have said it could be possible by the year 2028, less than 10 years from now. But this week, the Trump Administration condensed that timeline even further—Vice President Mike Pence directed NASA to put astronauts on the moon within the next five years, using “any means necessary.”

But it’s hard to see how NASA will meet this new timeline, given delays with developing its Space Launch System, and a proposed budget that doesn’t offer much more in the way of funding for the space program. Ryan Mandelbaum joins Ira to discuss how it will take more than just words to get humans back to the moon. Plus, how NASA’s all-female space walk was felled by the wrong spacesuits, and other science stories from the week.

Editor’s note: Upon further review, this article was updated on March 29, 2019 to rephrase the sentence around an all-female spacewalk. The original sentence misrepresented the issue. We regret the error.

Ryan Mandelbaum is a science writer and birder based in Brooklyn, New York.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. Later in the hour, a conundrum facing astronomers trying to measure the expansion of the universe. But first, for those of us looking forward to one day returning to the moon, experts have said it could be possible by the year 2028, less than 10 years from now.

But this week, the Trump administration condensed that timeline even further. Vice President Mike Pence directed NASA to put American astronauts on the moon within the next five years using, quote, any means necessary. But how realistic is that?

Here to tell us what we can glean from this announcement, as well as other short subjects in science, is Ryan Mandelbaum, science writer with Gizmodo. Always good to see you, Ryan.

RYAN MANDELBAUM: Hey, always great to be here, Ira. How’s everything going?

IRA FLATOW: Fine. Let’s talk about this. The Trump administration says it wants to get to the moon in five years. Is this possible, or is it wishful thinking?

RYAN MANDELBAUM: Well, I guess anything is possible with enough money, Ira. And I think that was the question that a lot of the people I spoke to had when they heard this was, OK, well, the Apollo mission was really expensive. Are you going to give us the money to send people to moon in time? I don’t know.

IRA FLATOW: [INAUDIBLE] my question. What would happen? What would have to happen? Would Congress have to suddenly say, hey, here’s a pile of money to do this?

RYAN MANDELBAUM: Yeah. I mean, well, so as you said, the current estimates are 2028. They want it by 2024. And I think it’s just this weird sort of dissonance for me. Because NASA is working on the SLS, this big rocket. They’ve been pushing these timelines.

And they’ve just delayed– in this, the new Trump budget has actually delayed part of the SLS. And actually, Brian Stein then said at this meeting that they would need that part in order to get astronauts to the moon. Well, Pence’s sort of the retort is that he wants private industry to do it. Whatever it takes, get us to the moon.

IRA FLATOW: That’s what whatever it takes means. It could be Elon Musk who gets [INAUDIBLE].

RYAN MANDELBAUM: Sure. And then I think part of that, it’s in the context of saying, he’s sort of declaring that we’re in a new space race against China and Russia. Which, OK–

IRA FLATOW: Well, we need– that’s what got us to the moon in the first place was a space race. Maybe we need a new space race.

RYAN MANDELBAUM: Maybe. You can’t see me rolling my eyes on the radio, but. [LAUGHTER]

IRA FLATOW: Oh. Speaking of all talk and no follow-through, NASA– and we had [INAUDIBLE] on the show talking about this– had to cancel the all-female spacewalk that was set to happen today, right? Because of sort of a wardrobe malfunction?

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. What happened was that NASA had announced earlier this month that Ann McClain and Christina Koch would be spacewalking together on the ISS. And that would be the first all-female spacewalk. And then what happened was that [INAUDIBLE] schedule due to these sizing issues had to be rescheduled for the sizing issues in the space suit. Because the upper portion of the suit was a little too big on McClain when she wore it on last Friday. So now, Koch is going to do it.

But now, the issue is, well, why haven’t we had an all-female spacewalk already? Like, that’s the thing that I think has been bugging me and a lot of people online is they’re saying, oh, it’s going to happen eventually. It’s not our fault. It’s a wardrobe thing. But OK–

IRA FLATOW: Well, if you have women on the space station, why are there not enough space suits for the women to wear if they have to go outside?

RYAN MANDELBAUM: Well, and I thought, well, why not already have had somebody? Why not have had another woman who could have just gone out there, right? I mean, there’s all sorts of ways you can think about it.

IRA FLATOW: But it didn’t happen.

RYAN MANDELBAUM: Did not happen. Maybe next time.

IRA FLATOW: Real soon now. Next, scientists who’ve been trying to hunt down where all the antimatter in the universe went think they’re finally on the right track.

RYAN MANDELBAUM: So you know that there’s a lot more matter than antimatter in the universe.

IRA FLATOW: That’s why we’re all here.

RYAN MANDELBAUM: That’s why we’re here. And scientists aren’t completely sure why. So what they’re doing is looking for places were the laws of physics are different between matter and antimatter. Because matter and antimatter look actually pretty much the same except for a small couple of differences.

And they’ve actually, the Large Hadron Collider scientists at the experiment LHCB found a new never-before-seen example of matter and antimatter seemingly behaving different in their collider. This is something that was first discovered in 1964. It was the 1980 Nobel Prize in physics. But now, they found yet another example of this laws of physics being different. And it’s textbook-making stuff.

IRA FLATOW: What do you mean? How different– where might the antimatter be? Does it predict where it might be found, or to make it, or–

RYAN MANDELBAUM: It predicts– they observed differences essentially in decay rates between particles and their antiparticle pairs. And it’s not enough to account for all the missing antimatter in the universe. That’s going to take more research, more physics, more theories. But for now, they’ve got another important source. And these are still important signposts for getting us there.

IRA FLATOW: Maybe the antimatter is hiding out with the dark energy somewhere [INAUDIBLE]. Next, there’s another measles outbreak that erupted in New York state. And this time, county officials have taken an extraordinary step to contain it.

RYAN MANDELBAUM: That’s right. County officials have announced a ban on unvaccinated minors in public places for 30 days or until they get the MR vaccine. So once it expires, it’s not happening anymore. It won’t be actively tracked by police, but it could be retroactively enforced.

IRA FLATOW: So they have to go out, and if they see somebody, they have to think that this is– how do you enforce that, I guess is what I’m getting at?

RYAN MANDELBAUM: I think you just say, if in two years or something– or after it’s over– you see that somebody’s child went out during this time, then I guess they’re arrested. But I mean, the infectious disease experts– this is not punishment. It’s to stop transmission and protect the vulnerable from this disease. I, mean we really are suffering this measles outbreak right now.

IRA FLATOW: Finally, it seems like we’ve got our next candidate for the Jurassic World Series. This is the largest T-rex ever discovered.

RYAN MANDELBAUM: That’s right. Scotty is the T-rex’s name. And it was actually first discovered in Saskatchewan in 1991. But it’s taken over a decade to both get it out of the ground and process the bones and get everything ready to actually study it. And Scotty is big.

IRA FLATOW: As Johnny Carson would say, how big is it?

RYAN MANDELBAUM: An estimated 19,555 pounds. So I think it’s important to note that he’s not physically– he’s more massive by estimates than the other dinosaurs, T-rexes that we have, not necessarily longer though. So what this basically does is, it just increases the upper limit of how big a T-rex could be. So in the next Jurassic Park, you can make the T-rex even bigger.

IRA FLATOW: Any special features of this T-rex?

RYAN MANDELBAUM: In fact, it looked like he lived a– well, we don’t know the gender. But it looks like it lived a pretty tough life. It had broken ribs, an infected jaw, and bite marks on its tail according to the paper.

IRA FLATOW: Well, if you’re the king of the jungle, everybody wants a part of you.

RYAN MANDELBAUM: That’s right.

[LAUGHTER]

IRA FLATOW: All right, Ryan. Thanks. That’s great.

RYAN MANDELBAUM: All right. Thanks so much, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: Ryan Mandelbaum, science writer with Gizmodo.

Copyright © 2019 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Katie Feather is a former SciFri producer and the proud mother of two cats, Charleigh and Sadie.