NASA Gets Its Moment In The Sun (Finally)

7:08 minutes

Even NASA has a bucket list. This summer the space agency plans to send a spacecraft into the sun’s atmosphere, a goal NASA scientists have had since the agency was first founded. What makes the mission possible now? A new heat shield that can withstand 2,600 degrees of heat on its exterior, while keeping sensitive scientific instruments at room temperature. Sarah Kaplan, science writer for the Washington Post, describes what happened when she saw the new heat shield in person. Plus, new evidence of human remains discovered outside of Africa continues to reveal more about when and why our ancestors first left the continent. And the Doomsday clock strikes two minutes until midnight!

Sarah Kaplan is a science reporter at the Washington Post in Washington D.C..

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. I Aim at the Stars was a 1960 film about Dr. Wernher von Braun, a former member of the Nazi party, who would make NASA’s dream of putting a man on the moon possible.

Well, NASA now actually is aiming at a star– our star– the sun. This summer, they’ll be launching a spacecraft toward the sun to conduct tests in its atmosphere, something they’ve never done before because– as Icarus found out– it gets a little hot out there. Here to tell us more about NASA’s moment in the sun as well as other short subjects in science is Sarah Kaplan, science writer for The Washington Post. Sarah, welcome to Science Friday.

SARAH KAPLAN: Hey, good to be here.

IRA FLATOW: So NASA gets to check mission to the sun off its bucket list soon, is that right?

SARAH KAPLAN: Yeah, this is actually something the agency has wanted to do since the ’50s, like basically since it was founded. And it wasn’t possible because, as you mentioned, it gets really hot up there. But now, because of advances in science and also advances in technology, they’ve finally managed to build a spacecraft that’s capable of withstanding this really intense heat. And so we’re headed this summer.

IRA FLATOW: Hmm– did you actually get to see the shield on the spacecraft?

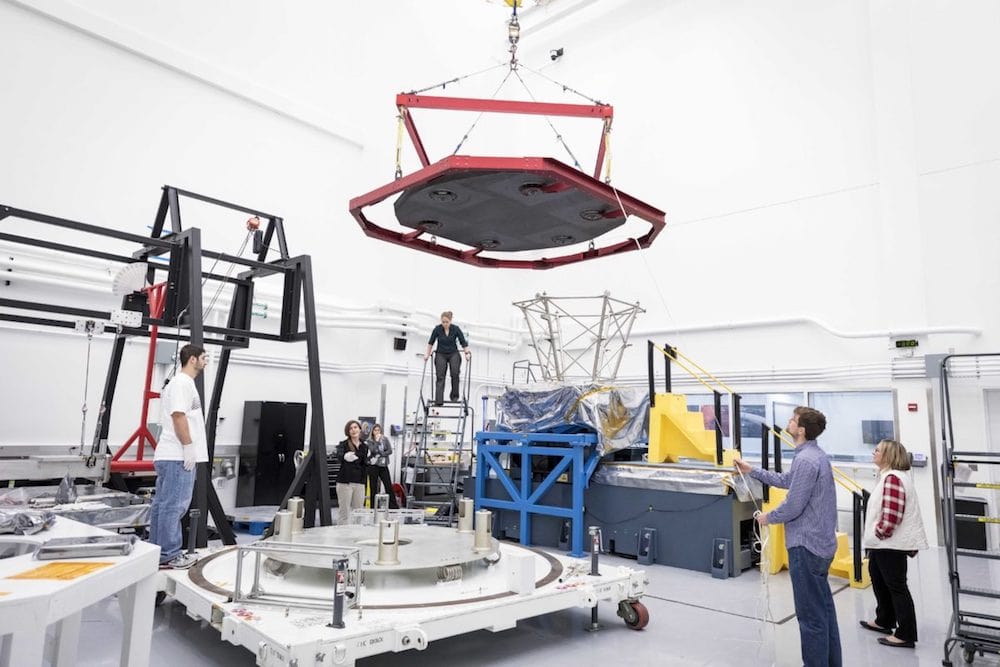

SARAH KAPLAN: Yeah, so the spacecraft is right now being tested and put together at Goddard Space Flight Center. And I got to go into the clean room, where they were putting it all together right before it went into a thermal testing chamber. So it’s this like big–

IRA FLATOW: Hmm.

SARAH KAPLAN: –empty warehouse space. And you have to be really careful when you go in that you don’t accidentally contaminate the spacecraft.

IRA FLATOW: So you didn’t contaminate it at all?

SARAH KAPLAN: This is where I confess that I actually sneezed while I was in the clean room, so hopefully I sneezed away–

[LAUGHTER]

SARAH KAPLAN: –from the spacecraft. Hopefully, none of my mucus is going to cause a problem for this mission that’s 60 years in the making.

IRA FLATOW: I think the solar radiation will sterilize all that away.

[LAUGHTER]

SARAH KAPLAN: Yeah, hopefully.

IRA FLATOW: Tell us what kind of tests they’re going to be doing in the sun’s atmosphere.

SARAH KAPLAN: So even though the sun is right there– it’s this like huge thing in our sky– it’s actually a pretty mysterious place. And there are two kind of big questions that NASA wants to answer. The first is something called the solar wind, which is the stream of charged particles that goes at supersonic speeds– so faster than the speed of sound– comes blasting out of the sun, and it goes all the way to the edge of our solar system. And we don’t really understand how it gets sped up so fast or where it’s coming from, so that’s one question that they’re trying to answer. And then the other is the atmosphere of the sun is actually hotter than the surface of the sun by about 300 times hotter–

IRA FLATOW: Wow.

SARAH KAPLAN: –which is like if you went up into the stratosphere and you were suddenly boiling– like it doesn’t make any sense. And so that’s another really big mystery that NASA is going to be trying to solve.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah well, that’s kind of interesting. All right– up next, scientists have discovered– new this week– the oldest human remains outside of Africa, and there were tools nearby. Tell us about that.

SARAH KAPLAN: Yeah, so this is this jaw bone from a human- homo sapiens– that was discovered in this cave in Israel. And the earliest known human remains before this were about 100,000, maybe 120,000 years old outside Africa, which is where our species originated. But these ones are 177,00 to as old as 194,000 years old, so like 50,000 years older. And that’s a big surprise because we just didn’t think that homo sapiens were so adventurous that early in our history.

And they’ve also got these cool tools nearby that they’re a very special processing technique, called Levallois, which means that you have to– it’s like where the way a sculptor sees the sculpture inside a stone before he starts carving– you have to be able to see the point that you want to make in a given piece of rock before you start chipping it away to make the tool that you want. And that requires sophisticated intellect–

IRA FLATOW: Right.

SARAH KAPLAN: –because you have to be able to see into the future. So that indicates that these guys were pretty smart.

IRA FLATOW: Wow, but does that mean we’re pushing back the timeline for when humans migrated out of Africa?

SARAH KAPLAN: Not necessarily. I mean it means that we’re adventuring out of Africa earlier, but those adventures might not have lasted very long. If you look at the DNA of modern people from Asia and Europe and the Americas, our genetics trace back to about 60,000 to 70,000 years ago. And so that was the final migration–

IRA FLATOW: Yeah.

SARAH KAPLAN: –that allowed humans to push out of Africa and colonize the world. So most of our evolution and development probably still happened–

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, yeah.

SARAH KAPLAN: –in the African continent.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s move on to our next story– because it’s hard to believe it’s been two decades since Dolly the sheep– but now Chinese researchers have cloned a pair of macaque monkeys.

SARAH KAPLAN: Mm-hmm. So instead of Dolly the sheep, you’ve got Zhong Zhong and Hua Hua– two cute little monkeys that were cloned using this. New technique– or it’s the same technique as Dolly the sheep– where basically you take a nucleus from the individual you want to clone– and that has all of its genetic material in it– and then you plug it into an egg cell–

IRA FLATOW: Right.

SARAH KAPLAN: –and that will develop into an embryo.

IRA FLATOW: I remember when we covered Dolly the sheep on Science Friday. It was such– wow, wow– cutting edge news. Now, it’s sort of like– ho-hum– they did a couple of macaques. What else are they going to do tomorrow.

SARAH KAPLAN: Yeah, I mean we’ve done it for a few species. And actually this technique has been used just for medical research on some human cells. So it is– it’s people have been working on it for a while. And the only reason it took so long with these monkeys is that there’s a lot of epigenetic factors in development that you have to consider. So for each individual species, you have to know exactly the right treatment for the embryo to get it to develop into a little, tiny monkey.

IRA FLATOW: And no one is saying this is leading to human cloning at this point.

SARAH KAPLAN: No– no– I mean the objective for this is more for medical research and basic research. We are a long way off, if ever, from human clones.

IRA FLATOW: Well, we’ll have to keep checking in about the health of those two, because it’s a long run to see how will they actually do.

SARAH KAPLAN: Yeah, but Dolly wasn’t too bad, so hopefully they will fare well too.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. And, finally, it’s a new year, which means the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists has moved the doomsday clock closer to midnight.

SARAH KAPLAN: Yeah–

[LAUGHTER]

SARAH KAPLAN: –I mean–

IRA FLATOW: It’s not a good thing is it?

SARAH KAPLAN: –every year they– no, if you needed some existential dread going into the weekend–

[LAUGHTER]

SARAH KAPLAN: –here it is. Because of developments in nuclear weapons and also humanity have continued inaction on climate change, the Bulletin has decided that we are now 30 seconds closer to midnight than we were last year. And this is actually the closest we have ever been since the height of the Cold War, since 1953. So the situation is pretty dire.

IRA FLATOW: I’m pulling out my Fallout Shelter manual and my Duck and Cover old videos.

SARAH KAPLAN: Yeah, stock up on canned goods.

[LAUGHTER]

IRA FLATOW: Sarah Kaplan, science writer for The Washington Post, thank you for taking time to be with us today. Have a good weekend.

SARAH KAPLAN: Yeah, thank you.

IRA FLATOW: Your welcome.

Copyright © 2018 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Katie Feather is a former SciFri producer and the proud mother of two cats, Charleigh and Sadie.