Speaking Multiple Languages Changes The Way You Think

17:16 minutes

Have you ever wondered how the language you speak shapes your understanding of the world around you? And if you speak two or more languages, how might that change the way you process information? Is your brain always thinking in multiple languages or are you toggling back and forth?

In many parts of the world, multilingualism is the norm. And in the United States, the number of people who speak a language other than English has doubled in the past two decades, from just about 11% to about 22%.

Dr. Viorica Marian has spent her career studying multilingual and bilingual people to better understand how their brains process information differently than their monolingual counterparts.

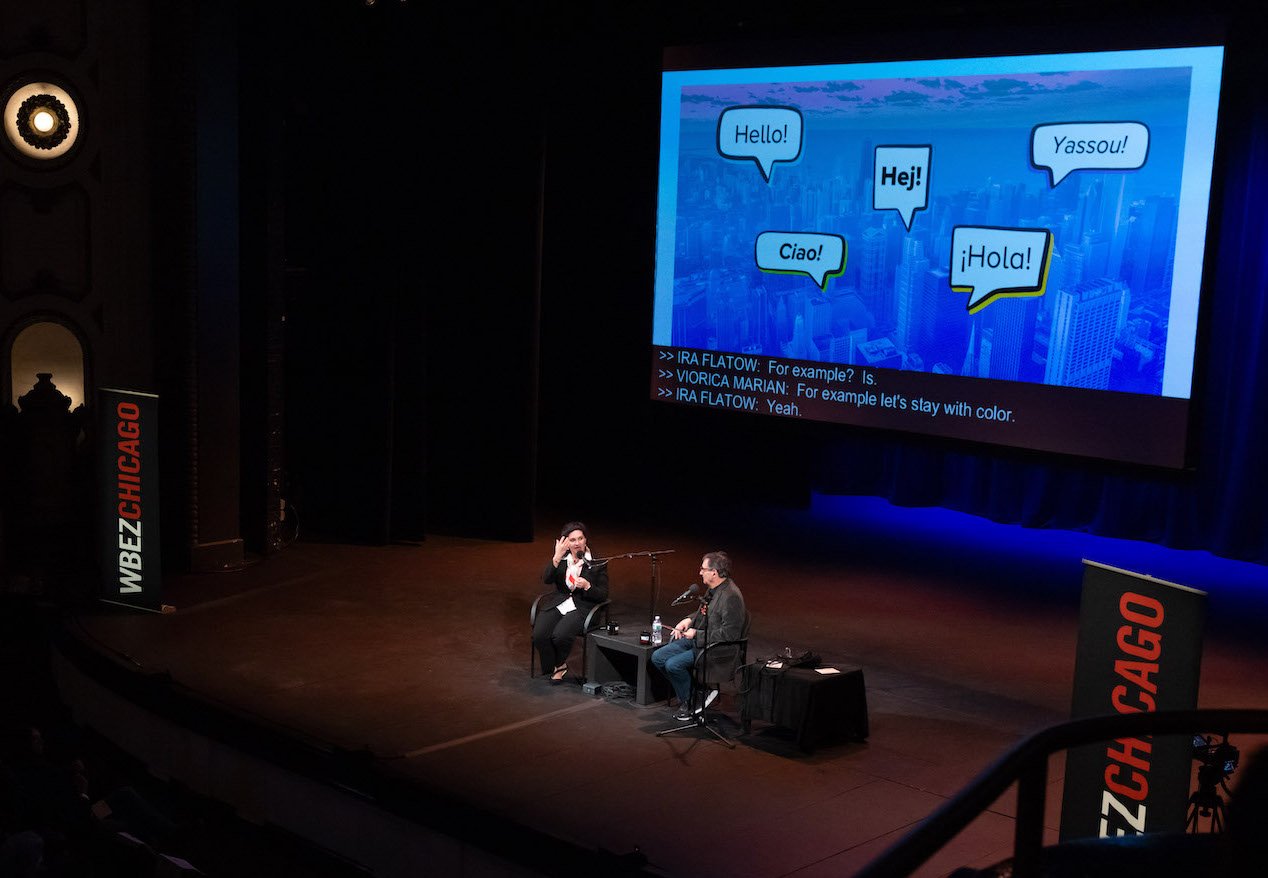

Ira talks with Dr. Viorica Marian, professor of communication sciences and disorders and psychology at Northwestern University, and author of the book The Power of Language: How the Codes We Use to Think, Speak, and Live Transform our Minds in front of a live audience at the Studebaker Theater in Chicago, Illinois, presented with WBEZ and Mindworks.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow.

This hour, we’re listening back to some fascinating conversations about social connection that we had a few weeks ago in front of a live audience at Chicago’s Studebaker Theater.

Have you ever wondered how the language you speak shapes your understanding of the world around you? I mean, what if you speak two languages or more? How might that change how you process information? Is your brain always thinking in multiple languages, or are you toggling back and forth?

Yeah. Well, contrary to what we experience in the US, in many places in the world, multilingualism is the norm. And even here in the US, the number of people who speak a language other than English has doubled in the past two decades, from just about 11% to 22%.

My next guest has spent her career studying multilingual and bilingual people to better understand how their brains process information differently than their monolingual counterparts. Dr. Viorica Marian is a professor of communication sciences and disorders and psychology at Northwestern University, based in Evanston, Illinois, and author of the recently published book, The Power of Language: How the Codes We Use to Think, Speak, and Live Transform Our Minds. Here’s our conversation.

Dr. Marian, let’s talk about multiple languages. Did you get interested in that because you are multilingual? How did you get interested in studying this?

VIORICA MARIAN: That was certainly part of it. I grew up in Eastern Europe. We spoke Romanian at home with my family. And then, outside the home, Russian was the official language everywhere in the territory of the former Soviet Union. And then I studied English in school and then French in college.

And this is actually very typical for many people in Europe– and not just in Europe. In fact, the majority of the world population– more than half of the world’s population– is bilingual or multilingual.

It is very common for people all over the world, on every continent, to grow up with two or more languages from early childhood and then learn additional languages later in life. But then, when I would go to a library or a bookstore, or in my coursework in college, most research– most science that I read– centered on people who only spoke one language.

So it very early became clear to me that by leaving out this huge segment of the population, we are getting not only an incomplete, but also an inaccurate, understanding of how language works, how the mind works, of human nature and humanity’s potential more broadly. This is what brought me to studying the interaction between language and mind, with a particular focus on people who speak multiple languages.

IRA FLATOW: And here in the United States, we speak mostly one language. So we’re in the minority of countries in the world because we’re just speaking one language.

VIORICA MARIAN: That’s true. But the numbers– the demographics– are changing. So as you mentioned, a little over 1/5 of American households speak a language other than English at home. And the proportion of people who are studying another language, especially now with all the apps that are available, is increasing.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s look at the statistics of people who speak more than one language. How is your brain processing language differently from people who speak only one language? Are you constantly switching back and forth between languages?

VIORICA MARIAN: Oh, that’s a really good question. Because we used to think that we’re switching back and forth between the two languages. In fact, people think that, when you use a language, you turn it on, you are done with it, you switch it off, switch the other one on, and switch between the two languages. But now we know that that’s not the case; that people who two or more languages keep all of them active in their mind to some extent.

And we see an image here. So for example, if you speak English and you read just three letters, P-O-T, your mind immediately activates multiple meanings of this word. Perhaps it’s the utensil you cook with or a pot that you plant or some of this– or maybe some other plants you’ve had familiarity with.

[LAUGHTER]

But if you speak Russian, that’s how you spell the word “mouth.” And that’s also how you pronounce the word “sweat.” And then, if you speak Romanian, that’s how you say, “I can” or “we can.” So in English, you activate the meaning– these four meanings, for example, or perhaps more– and then, from there, other related word forms and word meanings are activated. But if you speak two or three languages, this activation spreads across multiple languages simultaneously.

So you can think about it, if you were to throw a pebble in the water, you see these waves around. The further out you go, the bigger the circle becomes. And the closer to the pebble you are, the stronger the activation. So in people who speak two or more languages, all these languages are being activated.

IRA FLATOW: So as we’re thinking in parallel. It’s like parallel processing.

VIORICA MARIAN: That’s right. Our brain is this parallel processing superorganism that processes information in parallel at all times. So in people who speak multiple languages, there is a lot more interactivity and activation happening all the time.

IRA FLATOW: That is cool. That is really cool. I know you developed this clever way of determining if a bilingual, or multilinguals, are processing two languages at once using an eye tracking device.

VIORICA MARIAN: Yes. So we use multiple methods in the lab. We use eye tracking, EEG, fMRI. But with eye tracking specifically, we track people’s eye movements as they perform different tasks. So you may be sitting in front of a desk and you may be asked to pick up a marker, for example. If you speak English, and we ask you to pick up a marker, you will also make eye movements to marbles because marker and marbles sound similar.

So this shows us that, in your mind, both words are being processed and co-activated. But if you speak Russian, in addition to marbles, you will actually make eye movements to a stamp because the Russian word for “stamp” is [RUSSIAN]. That’s exactly what we do. We have people wear this eye cap– this eye tracker on a cap– and we record the eye movements as they do all sorts of tasks.

And by measuring their eye movements, we make inferences about their mental processes.

IRA FLATOW: There’s this very sort of seductive idea that multiple languages allows you to see the world in a different perspective. Is that true?

VIORICA MARIAN: Yeah. So there is some evidence for that. We think that there is this objective reality that we live in. But in essence, the reality that I live in is different from the reality that you live in or others live in because our perception of reality is shaped by our previous experience. And language– linguistic experience– is one of those experiences that shapes how we perceive the world.

So I’ll give you an example. The rainbow, we all think, if we speak English, that it has this set number of colors. But in reality, the rainbow doesn’t have these specific colors that we all draw when we are children. There is an infinite number of colors– the entire color spectrum– that’s present in the rainbow. Each color are switching one pixel at a time into another color.

So there’s an infinite number of colors. But the languages that we speak impose these boundaries– these color boundaries– on how we think about the rainbow. And people who have other words for color, in languages where there are more or fewer languages for colors, think about the rainbow differently.

IRA FLATOW: And not only that, but I noticed, in trying to learn other languages, inanimate objects have different genders to them. Some are male, some are female. Does that also influence?

VIORICA MARIAN: Oh, that’s a good question, too. So for those who only speak English, in English, all inanimate objects are referred to as “it.” But in many other languages, an inanimate object like a cup or a bottle is referred to as either she or he. And it sounds like a strange thing, but speakers of Romance Languages– French, Spanish, Italian, Portuguese, Romanian, for example– they very easily, from an early age, just learn what’s a he and what’s a she. And other languages may have more– like Russian has an “it,” a neutral gender.

And it turns out that grammatical gender influences how people represent mentally those objects. So in experiments done by Lera Boroditsky at Stanford and UC-San Diego, she asked Spanish-German bilinguals, or people who spoke Spanish and people who spoke German, to describe bridges or keys. And depending on the grammatical gender of the object and the language that you spoke, you described them very differently.

So if “key” was masculine in your native language, you tended to describe it as jagged and metal and sturdy and useful. And then, if it was feminine, you tended to describe it as delicate, small– just really mentally representing things differently.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday, from WNYC Studios. You’re listening to a conversation I had on stage in Chicago with Dr. Viorica Marian about the power of language.

You write in your book that, in older adults, being multilingual actually delays Alzheimer’s. There’s evidence for that. And you’re saying four to six years.

VIORICA MARIAN: Yes. This is one of the most exciting findings, I think, with real-world implications that comes from studying people who speak two or more languages. It turns out that constantly using two or more languages has this protective advantage against some of the cognitive declines that often accompany aging and that always accompany dementia.

So if you speak two or more languages, you are likely to show symptoms of dementia four to six years later than people who speak only one language. You have formed these connections between words, meanings, memories, life experiences that allow you to compensate functionally for the anatomical deterioration that your brain experiences. So for those of you who are past school age, it’s never too late, and it might actually be fun, to learn another language.

IRA FLATOW: All right. Speaking of fun, I have some of your questions here. And let’s see– OK, here, Aggo writes, I realize when I speak English, I am more proactive than when I speak Japanese. When my wife speaks Spanish, she is more social and chatty than when she speaks in English.

Tell me about that.

VIORICA MARIAN: That’s consistent with what people are finding in research studies. As I was saying before, the language that we speak brings to the forefront different aspects of our personalities and different cultural norms. So what is appropriate in the Japanese culture versus what’s appropriate in the American culture is going to be activated and influenced by the languages we speak.

One of my colleagues, who is a Japanese-English bilingual as well, says that she actually bows when she speaks on the phone when she speaks in Japanese, versus when she speaks in English because her language just activates the social norms. So the experiences that this person is describing is consistent with findings on personality tests. In fact, bilinguals score differently depending on the language they’re taking them in.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s go to Jeff S. Does Jeff want to take a chance and ask a question, which is a good one?

JEFF: I had a question about unspoken languages like computer languages. If someone is fluent in other languages that they don’t speak, could you also get some of the same benefits of bilingualism or multilingualism– for example, stalling dementia onset?

IRA FLATOW: Could you learning computer languages?

VIORICA MARIAN: Yeah. So it seems that you can see some of the executive function consequences with artificial languages. We don’t know yet about dementia and Alzheimer’s, but executive function differences, yes. So other symbolic systems that rely on math– like computer languages– do also change the way our brain works.

IRA FLATOW: Why do kids pick up multiple languages so much faster than adults?

VIORICA MARIAN: Yeah. So when we are born, we can hear and distinguish between the sounds of all of the world’s languages. Just like with the rainbow, remember I was saying there’s an infinite number of colors. There is an infinite number of sounds that we could perceive when we are first born. We are sort of citizens of the world.

But by our first birthday, our brains get tuned in to the sounds of our own language and we become citizens of one country or one language– or perhaps more than one language. And in babies who are exposed to more than one language, this perceptual window is open for a little bit longer.

There are multiple reasons why children learn languages easier. There is constant linguistic input for them. Their brains are also still developing. They are much more plastic.

So it’s not just language. There are other things that our brains just pick up easier when they are younger and plastic. But we actually now know that you can learn another language and you can learn it to fluency at any age.

We used to think that there is this critical age period, after which you cannot learn another language to fluency. That’s actually not the case. So your brain can learn another language at any age.

And it may be more difficult because you’re doing so many more things in your daily life. You’re not just having– I mean, if you lived the life of a child and someone took care of you and spoke with you in this, “hi, baby,” contoured speech you would learn differently than if you were thinking about a million other things that you have on your mind.

IRA FLATOW: Last question from Rebecca. How does multilingualism support the brain’s capacity to form emotion concepts and express emotions? Is there a connection or does it influence it?

VIORICA MARIAN: Yeah. So this goes back to how much of our thought and emotion and our life experiences are tied to language. And quite a bit actually. So that’s why when you are in therapy or when you’re growing up, you’re often told to label your emotion. Sometimes labeling your emotion helps you process it.

Languages vary in the kind of words that they have for emotion. So people express emotion and report feeling differently depending on the labels that they have for emotion. So yes, emotions are tied to language and can help us process our experiences different. By labeling them, we understand or we process our feelings differently.

Like I mentioned before, there is now research on psychotherapy with bilinguals also showing that you can distance yourself from feelings by switching to a different language than the language in which a traumatic experience happened, or you can experience closeness differently in your interpersonal relationships. People report feeling differently when they’re being told “I love you” in their native language versus in their non-native language.

So language has this very powerful effect in how we connect with others. If we spoke a certain language with our family, we may associate it with warmth– or the opposite. It depends on the kind of experiences we’ve had, yeah.

IRA FLATOW: That’s terrific, Viorica. We’ve run out of time. Thank you for taking time to be with us today.

[APPLAUSE]

Dr. Viorica Marian, professor of communication sciences and disorders and psychology at Northwestern University and director of the Bilingualism and Psycholinguistics Research Group, based in Evanston, Illinois. Thank you for coming down.

[APPLAUSE]

That event was in collaboration with WBEZ and Mindworks. And if you want to know more, yes, go to sciencefriday.com/events.

Copyright © 2023 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

John Dankosky works with the radio team to create our weekly show, and is helping to build our State of Science Reporting Network. He’s also been a long-time guest host on Science Friday. He and his wife have three cats, thousands of bees, and a yoga studio in the sleepy Northwest hills of Connecticut.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.

Shoshannah Buxbaum is a producer for Science Friday. She’s particularly drawn to stories about health, psychology, and the environment. She’s a proud New Jersey native and will happily share her opinions on why the state is deserving of a little more love.