Rewriting Sharks’ Big, Bad Reputation… For Kids

16:56 minutes

It’s that time of year when sharks are on our minds. Summer is filled with Shark Week content, viral reports of attacks, and shrieks on the beach when someone spots a fin in the water… from a dolphin.

It’s that time of year when sharks are on our minds. Summer is filled with Shark Week content, viral reports of attacks, and shrieks on the beach when someone spots a fin in the water… from a dolphin.

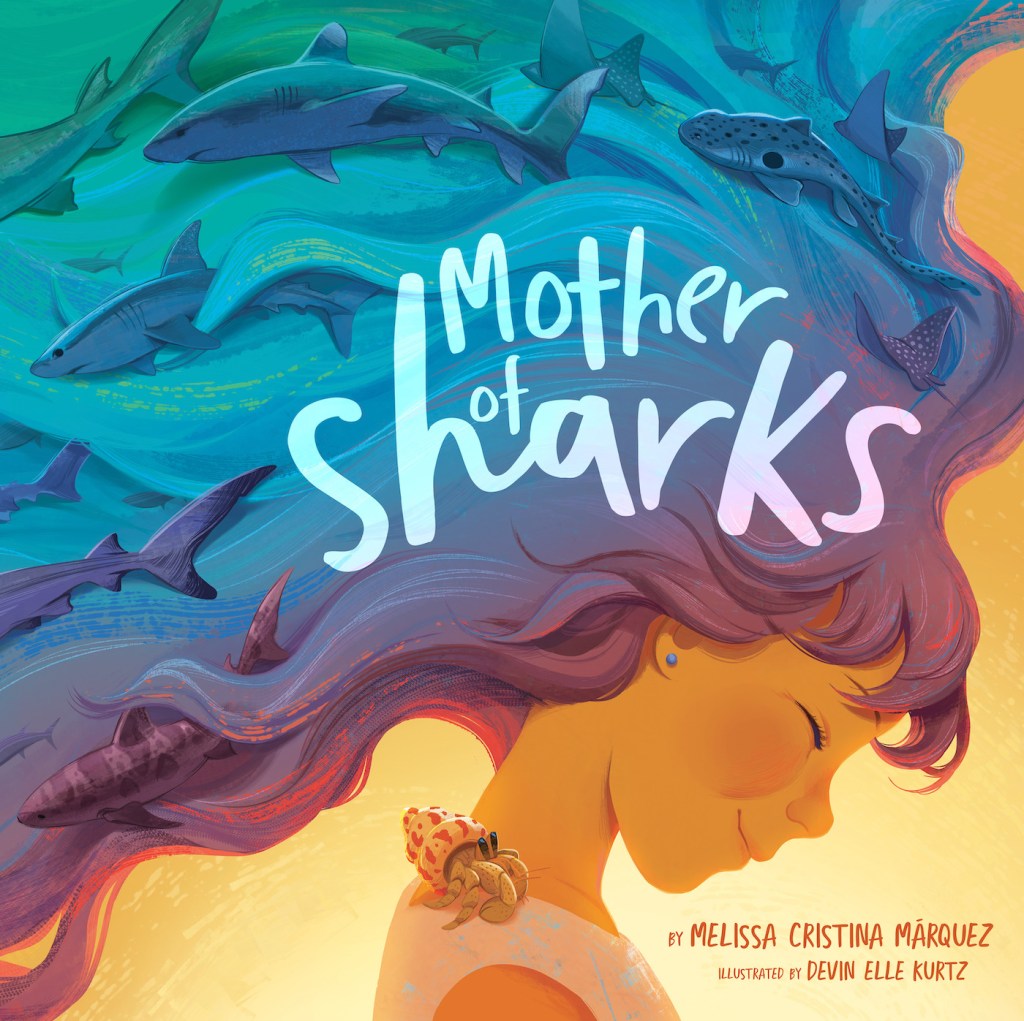

But sharks don’t deserve this bad reputation. They are beautiful, fascinating, and—more than anything—the Earth needs them. A new children’s book called Mother of Sharks by Melissa Cristina Márquez, aims to teach kids exactly that.

Ira talks with Márquez, a shark scientist and wildlife educator, about the book, shark conservation, and why she loves sharks so much.

Where To Get “Mother of Sharks”

Where To Get “Mother of Sharks”Want to read Mother of Sharks along with us? Click the link below to get it for yourself or a young ocean-lover in your life.

SPEAKER: It’s that time of the year, when sharks are on our minds. Summertime is filled with shark news, viral reports of attacks, shrieks on the beach when someone supposedly spots a shark in the water when it was really a dolphin or a seal or the Loch Monster. But sharks don’t deserve this bad reputation that we’ve assigned them. They are beautiful and fascinating and more than anything, we need them. A new children’s book called Mother of Sharks, aims to teach kids exactly that.

Joining me is the author of this book and mother of sharks herself, Melissa Cristina Márquez, shark scientist and wildlife educator based in Perth, Australia. Welcome to Science Friday.

MELISSA CRISTINA MARQUEZ: Thanks so much for having me. Absolute pleasure. Long time listener, so it’s really cool to be on the other end of it now.

SPEAKER: Well tell us, how did you get the nickname, mother of sharks?

MELISSA CRISTINA MARQUEZ: So I, during my master’s degree, lived in New Zealand, and I was volunteering at a local aquarium there and became good friends with another one of the volunteers there. And he saw me kind of like cooing over and getting really excited over the sharks that we had in the tank, and he just gave me the nickname mother of sharks, very similar to, I’m assuming Mother of Dragons, from Game of Thrones, but I’ve never seen the show, so I wouldn’t know.

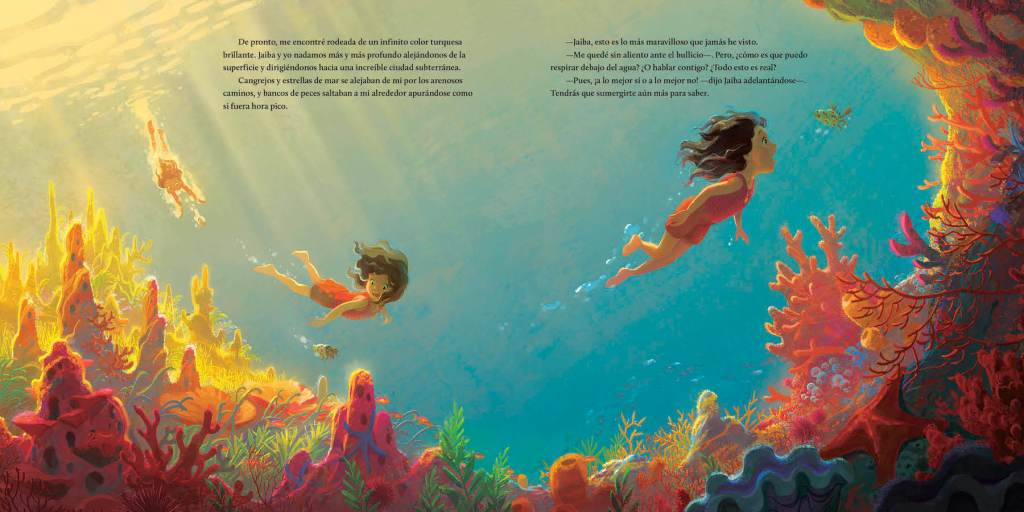

SPEAKER: It’s a big compliment, so I’ll let you know that. Let’s talk about your book instead. Your book tells the story of a little girl named Mellie, exploring the tidal pools of San Juan, Puerto Rico. Are you Mellie in this story?

MELISSA CRISTINA MARQUEZ: Yeah. So my nickname that my family, who speaks Spanish, calls me as Mellie, so little Mellie is myself.

SPEAKER: So how are you reflected in this book? Tell me the story behind that.

MELISSA CRISTINA MARQUEZ: So essentially, the book is about not just representation and diversity of sharks that you get to see in it, but also, representation of the people who study them. Growing up, I never saw a Latina marine biologist, let alone a Latina shark scientist, so even though I really wanted to be one, I never really saw myself being one because I never saw one like me.

And so the story shows this little Mellie perusing through the tidepools, as she used to do in San Juan, Puerto Rico. And she comes across a hermit crab that says, hey, do you want to go on an adventure? And Little Mellie is not one to say no to adventures, so off they went. And it was actually a time traveling adventure to the future to see what her future could be like and would end up being like.

And her, eventually– again, spoiler alert– becoming the mother of sharks. And so it really is a book about representation and showing kids that you can dream as big as you want and jump the shark, per se, and you have every right to dream as big as you want.

SPEAKER: So it’s really kind of an autobiography then.

MELISSA CRISTINA MARQUEZ: Yeah, sprinkled with a bit of fantasy in there. The book, outside of the time traveling hermit crab, is very, very true to what my life is, so that is how I got interested in the ocean was just going around the tidepools, figuring out what was there, and hermit crabs were the very first thing.

I remember begging my mom to take home in a bucket, Little Mellie was not an aquarist though, and many of those hermit crabs did not make it. Rest in peace. But they fostered a bunch of just curiosity about the ocean, and so it was really them who started my journey into the ocean and wanting to become a scientist that studied it.

SPEAKER: Interesting. So why did you pick on sharks to be interested in and not whales or dolphins or something else?

MELISSA CRISTINA MARQUEZ: Ah, those are too mainstream. No, the real reason is, so I moved from Mexico to the States later on and parents sat me in front of a TV. And because it was summer when we moved, I happened to be having just turned the channel to the Discovery Channel and ended up watching Shark Week.

And so Shark Week was the first thing that kind of hooked me on to sharks, because suddenly, I saw this giant great white shark breaching out of the water, so jumping out of the water, and I was hooked. Immediately, I was like, that’s it. That’s what I want to study. And that phase never went away.

SPEAKER: Well, that brings me to this question about Shark Week, because I think in watching Shark Week over the years, it makes people more fearful of sharks. And then you had the film, Jaws, that really shaped the way a lot of us think about sharks, the jaws-ification of how we view them, but what’s really scary is an ocean without sharks is one of your main points.

MELISSA CRISTINA MARQUEZ: Yeah, definitely. It’s one of those things that a lot of people don’t realize that there’s more to sharks than this sensationalized, terroristic image that they have. They are so important, not just to our oceans, but also, to our economies. They bring in millions of dollars into local economies when people travel go around the world to go see sharks and interact with them in some sort of way. Not to mention, they’re also really culturally important to a lot of communities around the world Australia is a great example of that.

Here, we’ve got many Aboriginal peoples and communities who, very strongly identify with sharks or have sharks as a creation story. And so the more you take away those predators, the more you start chipping away at all of these ways that sharks are important, not just to the ecosystem, but also, to people’s wallets and to the culture.

SPEAKER: Let’s talk a bit about how sharks are important to the ecosystem. Tell us what role they play?

MELISSA CRISTINA MARQUEZ: Sharks are a bit like– I like to think of them as the puppet masters in that they just rule everything. Now, there is this misconception that sharks are the top dog, per se, and not all of them are. There’s actually over 500 different species of sharks. I don’t think many people know that.

SPEAKER: Wow.

MELISSA CRISTINA MARQUEZ: Yeah, it’s pretty nuts, isn’t it? A lot of people, when you say shark, they’re like, oh, tiger shark, great white shark, hammerhead, bull shark. Is that about it? And I’m like, no, no. There is so, so many different species that not all of them have the same exact roles.

But for the most part, they play a crucial role in maintaining the health of our oceans, and their significance really extends beyond their intimidating reputation. Ecologically, economically, and culturally, they really contribute to the health of our marine and in some cases actually here in Australia too freshwater ecosystems as well, because there are some shark species that are only found in freshwater.

And so in regards to how they impact the ecosystem, they have a profound impact on food webs, regulating prey numbers, promoting biodiversity within ecosystems, and their feeding habits really shape the behavior, morphology, life history of prey species that results in significant changes in vegetation abundance and diversity. So removing predators like them can really disrupt the delicate balance of food webs, which then leads to alterations in abundance, diversity, diet, and even body condition of some of these marine species.

SPEAKER: Very interesting. So then how worried should we be now? Are sharks threatened to be put out of existence?

MELISSA CRISTINA MARQUEZ: Yeah, that’s a really good question. So a 2021 report showed that over the last 50 years, global shark and ray populations– because stingrays are actually relatives of sharks. Think of them kind of like as cousins. So global shark and ray populations, over the last 50 years, have fallen more than 70%.

And a new study that just came out earlier this year found that almost 2/3 of sharks and rays that live around the world, coral reefs are threatened with extinction. And that potentially, has dire knock off effects for the ecosystems and coastal communities that depend on sharks, essentially. So science says we are starting to reach that point of no return, but there are some encouraging signs that we’re seeing that conservation efforts are starting to work for some local shark populations, such as great whites and hammerheads. And that’s thanks to strong government bans, policies, and quotas.

So it’s not too late to reverse what’s happened, but the window to do so is really shrinking. We’re lucky that marine wildlife is quite remarkably resilient. There is the possibility for recovery. We just need to have urgent and widespread conservation interventions at this point.

SPEAKER: When you say conservation interventions, I know people who go out shark hunting. Is hunting the greatest threat, or are other things bigger threats?

MELISSA CRISTINA MARQUEZ: So overfishing is definitely the biggest threat that sharks and rays face in our oceans, overfishing and the bycatch, so when you’re capturing sharks instead of capturing what you actually want to capture like other species of fish or anything like that. And so those are the biggest threats that sharks face. It’s not so much just, say the recreational fishermen that you see down the street who is capturing sharks. He has an issue. I mean, it doesn’t help whatsoever, but it’s more of the big commercial fisheries.

So that’s why one of the biggest things that shark scientists say when it comes to helping sharks is not just educating yourself about them, but also, making sure that you have sustainable seafood choices, if you do eat seafood, because that’s the biggest way that you can help sharks.

SPEAKER: This season, I’ve seen lots of headlines like, tourist viciously attacked by a shark or shark attacks on the rise. Are they actually on the rise, or are we just hearing more about them?

MELISSA CRISTINA MARQUEZ: I mean, it doesn’t surprise me that we’re hearing more about shark attacks because we’re constantly glued to our phones. We’re constantly glued to our computers. And so these sorts of things will allow you to know about events across the world that otherwise, you wouldn’t have heard of before.

And so one shark bite interaction could be shared hundreds of thousands of times constantly on your feed, on any of the social media platforms, and it makes you seem like it’s constantly happening, but it is, statistically, a really, really rare event. And so I think part of it is the hype that comes from the media. At the end of the day, shark attacks, those are always going to be something that are sensationalized, and that sells, because it is such a attention-grabbing issue.

SPEAKER: They’ll always try to find reasons for it. And one that you hear a lot that is that with climate change, the waters are warming, bringing closer to shore a school of fish that sharks may feed on. Climate change may have nothing to do with it?

MELISSA CRISTINA MARQUEZ: Yeah. I mean, the problem is a lot of people want one simple answer as to why shark bites happen. There’s not going to be one single answer. Our oceans are so dynamic, there are so many things that are happening at once that would lead to this very rare event happening. And unfortunately, we don’t have all the answers.

And I understand that it’s very frustrating from a public stand point of being, like why can’t you tell us why this happens, but we are really just scraping the top of the barrel when it comes to understanding shark behavior and especially now that it is changing because our oceans are changing. Our ecosystems within those oceans are changing, which means the way animals, such as predators and prey move is changing, it’s like we’re almost starting back at zero in some ways.

So yeah, there’s no one single thing to point out like, ah, yes, this is why shark bites happen, it’s so individualistic for every single event that happens. But again, there’s so statistically rare, which also makes it hard to study because they are so rare.

SPEAKER: This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. So what do you tell beachgoers who are nervous about sharks in the water this summer?

MELISSA CRISTINA MARQUEZ: To be honest, probably, sharks are the least of your worries that you should have when you’re going to the beach. You have more of a risk of getting into a car accident on the way to the beach than you are of getting bit by a shark. But here in Australia, we have drones, we have shark spotters, we actually even have helicopters that do specific, almost like flybys to go over certain beaches during certain times to have a look out for sharks.

And that’s one of the best ways to coexist with these animals is having that proactive monitoring that happens, but of course, that takes time and that takes money and resources. But if you’re really, really nervous, I mean, the number one way to guarantee you’re not going to get bit by a shark is stay out of the water.

SPEAKER: Yeah, speaking of going to the beach or being around sharks, I know that you dive with sharks. What’s that like? Set the scene for me.

MELISSA CRISTINA MARQUEZ: Oh, it’s incredible. I’ve been really lucky to have gone diving with many different species of sharks, both in and out of cages. And every single time is as magical as the last. For me, it almost feels like the first time every single time I do see one, even for the species that I’ve seen hundreds of times now.

It’s just magical to share a space with an animal that is over 450 million years old. I mean, sharks have been around since even before the trees. And so getting to share the ocean with them, getting to see how curious they are in their own environment and just every time I’ve gone diving with sharks, less and less do I see this hyped-up version of what the media and movies and horror stories say that sharks are.

And instead, I see a really intelligent, curious, graceful animal. And it makes me wish that everybody had the opportunity to go diving with these animals because I think they’d see them a little bit different if they got the chance to actually be in the same space as them.

SPEAKER: Yeah, do you have a favorite shark you like to dive with?

MELISSA CRISTINA MARQUEZ: I do. Tiger sharks.

SPEAKER: Why?

MELISSA CRISTINA MARQUEZ: It’s going to sound completely counterintuitive. They don’t personal space. If you are starting diving with sharks, maybe don’t go with the tiger shark just right off the bat because they do not personal space, whatsoever. But I love them because they’re just very charismatic, they’re very curious, and just, they’re gorgeous. I mean, they’re known as tiger sharks because they’ve got these bright stripes on the side of their body that acts as incredible camouflage against the ocean, which you wouldn’t think it would, but it does.

And again, just having them come up close to your face really is just something else.

SPEAKER: That’s cool. I can’t let you go without asking, what’s your weirdest, wildest, coolest, shark fun fact?

MELISSA CRISTINA MARQUEZ: I already gave my fun fact away of the over 500 different species of sharks, but I’ll give you an even cooler one. There are some species of sharks that can live over 300 years, some scientists even guesstimate over 500 years.

SPEAKER: No.

MELISSA CRISTINA MARQUEZ: Yeah. Greenland sharks.

SPEAKER: Greenland sharks. Do they live near Greenland?

MELISSA CRISTINA MARQUEZ: They do. They do live in the cold–

SPEAKER: In that cold water up there?

MELISSA CRISTINA MARQUEZ: They do live in the colder parts. However, there was one, I think, last year that, for some reason, was spotted off of Belize. So maybe they got a bit sick and tired of the cold and decided to come down to the Caribbean.

SPEAKER: On vacation?

MELISSA CRISTINA MARQUEZ: Yeah, on vacation.

SPEAKER: Well, Melissa, I want to thank you. Fascinating stuff. Thank you for taking time to be with us today. A terrific book.

MELISSA CRISTINA MARQUEZ: Thank you so much for having me. I really appreciate it.

SPEAKER: Melissa Cristina Márquez, shark scientist and wildlife educator based in Perth, Australia. Before we go, if you’re looking for more books about epic creatures, join the SciFri Book Club for our August pick. We’re reading John Scalzi’s The Kaiju Preservation Society. It’s a sci-fi story about a mysterious organization set on an alternative universe Earth.

It features Godzilla-like giants. Yes, it’s a great summer read, and you can find out everything you need to know, including how to enter to win a free book all on our website, sciencefriday.com/bookclub. That’s sciencefriday.com/bookclub.

Copyright © 2023 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Rasha Aridi is a producer for Science Friday and the inaugural Outrider/Burroughs Wellcome Fund Fellow. She loves stories about weird critters, science adventures, and the intersection of science and history.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.