A Monterey Bay Aquarium Scientist Gives Fun Facts About Cephalopods

16:36 minutes

It’s the most wonderful time of the year! No, not the holidays—it’s Cephalopod Week, and SciFri uses any excuse to celebrate the mysterious squid, the charismatic octopus and the cute cuttlefish.

If anyone matches SciFri’s enthusiasm for marine invertebrates, it’s the folks at the Monterey Bay Aquarium. Guest host Sophie Bushwick talks to Christina Biggs, senior aquarist at the Monterey Bay Aquarium in Monterey, California. Biggs spills behind-the-scenes details about everything from raising cephalopods from eggs to how their dietary preferences can resemble those of picky toddlers.

“She’ll come right over to grab food,” Biggs says of one of the aquarium’s Giant Pacific Octopuses. “And on Sardine Sundays, she just tosses it right over her head and just waits for something better.”

Can’t Get Enough Of Cephalopod Week? It’s still not too late to cephalo-brate!

Listen to the latest episode of SciFri’s Science Diction podcast, where host Johanna Mayer is quizzed by SciFri staff cephalopod enthusiasts about the origins and stories behind names of our favorite marine dwellers.

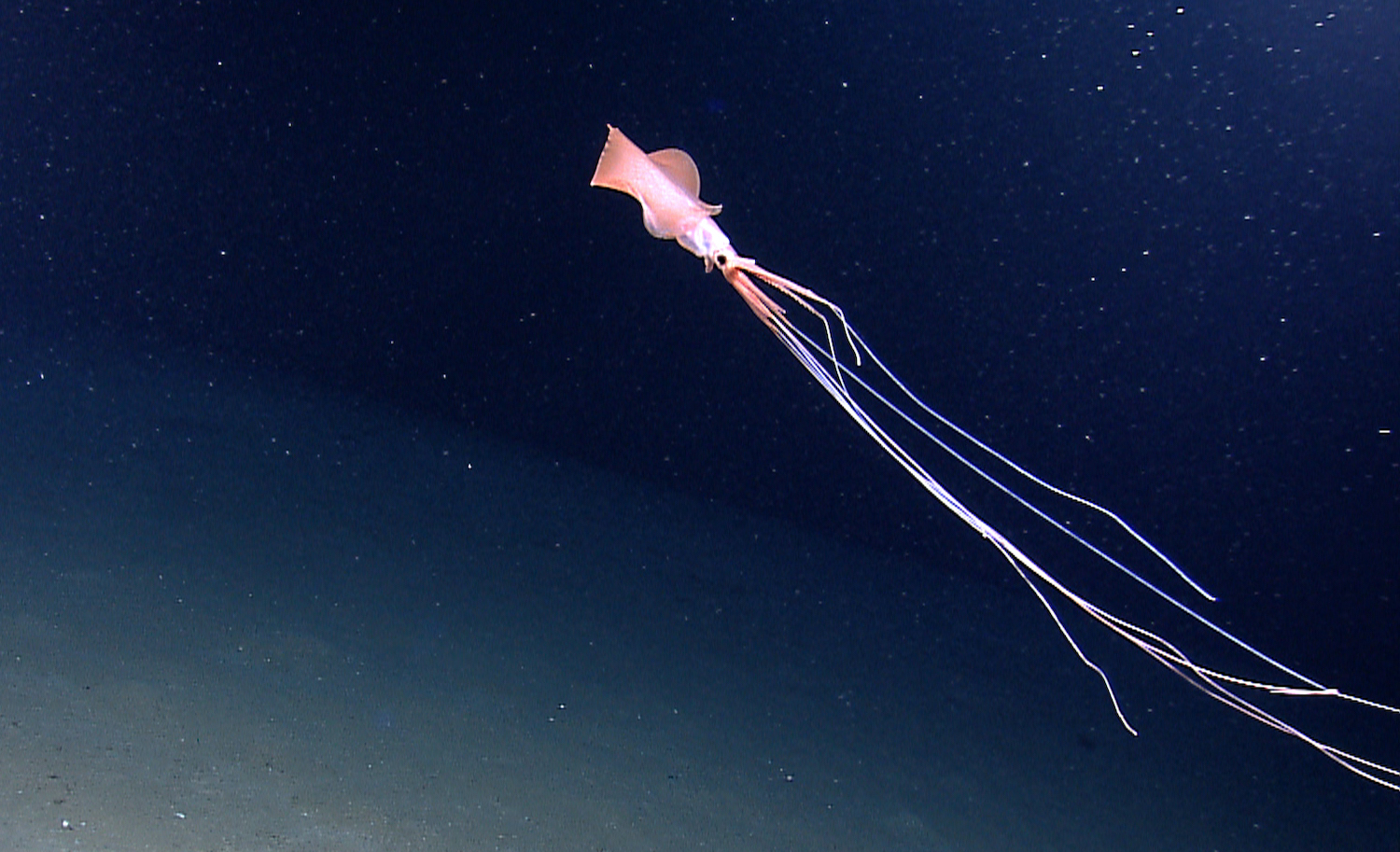

Have you heard of the bigfin squid? Its elbowed, spindly appendages have long stunned the public. But scientists say there is more to this deep sea dweller than its ghostly appearance. In the latest SciFri Rewind, where we dive into our archives, we revisit a 2001 interview with cephalopod curator Mike Vecchione when he first told us about this “mystery squid” in the deep.

From the dazzling camouflage of the flamboyant cuttlefish to the squishy dumbo octopus, watch our fun cephalopod-themed videos on TikTok!

@scifriThey almost called this species “adorabilis” ##octopus ##cephalopodweek ##mbari ##deepsea ##science ##wow ##cute ##adorable ##squishy♬ I shall call him squishy – chl0e

This year, we had a wave of online events! We had our minds blown with cephalopod facts during our special cephalopod edition of SciFri Trivia Night. And we gathered with some of the squiddiest humans and experts we know for a spectacular Cephalopod Movie Night. Watch (or re-watch!) our Movie Night below, and mark your calendars for our next weekly SciFri Trivia!

With every donation of $8 (for every day of Cephalopod Week), you can sponsor a different illustrated cephalopod. The cephalopod badge along with your first name and city will be a part of our Sea of Support!

Christina Biggs is senior aquarist at Monterey Bay Aquarium in Monterey, California.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: This is Science Friday. I’m Sophie Bushwick. It’s the most wonderful time of the year. Forget the holidays. It’s Cephalopod Week. It’s the time where we celebrate our favorite invertebrate sea dwellers like squid, octopuses, and cuttlefish to name a few.

It’s hard to find a group of people who care more for a wide range of cephalopods than the folks at the Monterey Bay Aquarium in California, so we’re going to go behind the scenes of one of the world’s most beloved aquariums to learn more about these wonderful creatures. Joining me today is my guest, Christina Biggs, senior aquarist at the Monterey Bay Aquarium in Monterey, California. Welcome to Science Friday.

CHRISTINA BIGGS: Hi, Sophie. Thanks so much for having us during Cephalopod Week. It’s Cephalopod Week for us every week here at the Monterey Bay Aquarium. We’re really glad to join you.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: Awesome. And just to note that this segment was recorded in front of a live Zoom audience. To learn more about attending a future live recording, visit sciencefriday.com/events. Cristina, let’s start with the basics. How many cephalopods do you have at the aquarium?

CHRISTINA BIGGS: Currently, we have 10 species of cephalopods. We have anywhere usually from eight to up to 20, depending on how many exhibits we have open, the time of year, and those types of things. But right now, we have 10 and about seven to eight that we’re actually culturing here behind the scenes.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: And are all the cephalopods on display? Or are there some that are behind the scenes?

CHRISTINA BIGGS: We have a lot. I would say only about 10% of the cephalopod that we have here in the building are on display at any given time. We do a lot of culturing here, so we’re raising up babies continually. As you know, cephalopods are very short lived. A lot of them, span is about six months to, GPO, the very big ones, the octopuses, will live maybe three to five years. But a lot of the squids live about a year. So we have a constant culture going so that we have animals that we’re able to offer to the public.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: And can you explain what exactly you mean by the term culturing?

CHRISTINA BIGGS: Sure. In the very beginning, this exhibit has been open for, I think, about eight years now. So in the beginning, we received wild-caught eggs. There are fishermen who often pull them up accidentally, and they’ll offer them to us. And so we receive eggs from the wild.

And then over the years, we’ve developed techniques– I think we’re one of the only aquariums in the world that has figured out how to culture some of these animals. So we take the eggs. We figure out what they need to stay healthy until the embryos inside grow up. And then we hatch them out.

And when they hatch, then you have to try to figure out what to feed them. And so we have a lot of different food options here. And as they grow up, then they have differing habitat needs, so we have to figure out how to grow with them as they grow and change our techniques.

Like I said, their diets change over time. And then, hopefully, if they’re comfortable enough, they’ll decide mate here in the aquarium. And we can take those eggs, and they’ll start the whole process all over again. SOPHIE BUSHWICK: And we’ve got a lot of listener questions now about cephalopod intelligence. Abril has a question about human versus cephalopod brains. Go ahead.

ABRIL: Hi, I’m Abril. I was wondering, compared to humans, what makes an octopus brain different from a human brain?

CHRISTINA BIGGS: Yeah, octopus brains are very different. I’ve heard some people describe them as alien brains. So you know how humans have one big giant brain that’s kind of connected to their spinal cord that goes out to all their nerves? Well, octopuses actually have– their network goes all the way throughout their bodies.

So they have– basically, they say they have eight brains. They have one brain for each one of their arms, and those brains connect independently of the other ones. So each arm can be doing something different.

And actually, all of those suckers– you know how their arms are lined with suckers? All of those suckers can also be acting independently, so everything can move differently from the other part of the body, which is why they’re able to do such amazing– you’ve seen all these amazing things, where they can squeeze through things and the texture changes and the color changes. All of those things are done with this sort of diffused neural net that they have.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: That’s incredible. I’m imagining if all of my fingers had a different brain controlling them. But to move from brains to stomachs really quickly, what do you feed all of these cephalopods? And do they all eat the same things?

CHRISTINA BIGGS: That’s a really good question. So we have a whole host of both live foods and frozen foods. When our hatchlings catch, we have to start out with live food. Cephalopods don’t recognize things that aren’t alive. Like the salmon we eat on our plates, that wouldn’t look like food to them.

So we train them over time. Because they’re so intelligent, we can get them to work with us on the diet because maintaining these live foods are also very difficult. It’s like keeping a whole nother set of animals in the aquarium. So we feed them everything from [INAUDIBLE] shrimp, to grass shrimp, to live fish, and then we transition them to frozen things, almost the same things– frozen [INAUDIBLE] frozen shrimp, and then we’ll move on to various fishes.

A lot of the octopus will eat clams. They eat clams in the wild. You’ll see that they have those really tough beaks that drill into things, so that is a good form of enrichment for them. So we’ll offer them live clams, live oysters. We have both fresh and frozen crabs that they eat. That’s another thing that they have to work really hard to cut apart. And they also like the hunt. They’re great hunters. So those are some of the foods we feed here.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: Have you noticed if any might have– any individual might have like a favorite food? Or do you think that they’re just sort of whatever they get they like?

CHRISTINA BIGGS: Oh, no. They definitely have preferences. There are some– that GPO I’m working with right now, the Giant Pacific Octopus, definitely does not like the fish that I feed. We have sardines here. And she’ll come over. I have her train to come over to what we call a station.

And she’ll come over to grab that food. And on Saturday and Sunday, she just tosses it right over her head and just waits for something better. So yeah, they definitely have preferences.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: And listener Robin has a question about finding cephalopods for the aquarium. Go ahead, Robin.

ROBIN: Hey, so I know that you all talked earlier about cultivating cephalopods on the aquarium. But what do you do to ensure that the cephalopods that come in from the wild are ethically sourced?

CHRISTINA BIGGS: That’s a really good question. So we have vendors that have been vetted by our veterinary staff here and the ethics committee and relationships that we’ve developed. We often travel to meet these people and to see what their setups look like. And definitely, it’s one of our top priorities. We certainly follow all of the AZA recommendations on ethical animal treatments. They’re long-term relationships.

But like I said, right now, our cultures here have been established for about eight years. And so we just do this groundbreaking work, where we raise them from egg here and don’t have to take from the wild.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: And we also have a couple of questions about the cool abilities that cephalopods have. So let’s start with listener Kimberly, who has a question about camouflage. Go ahead, Kimberly.

KIMBERLY: We were wondering– we have a whole classroom full of students. And we were wondering– this right there.

AUDIENCE: How can you identify or know when an octopus is camouflaged or not?

KIMBERLY: Since they’re color blind. Aren’t they color blind?

CHRISTINA BIGGS: They are color blind. So I think that’s two questions. One, how do we find them? Well, in the wild, one of the ways that we can find them, if they are camouflaged, is they tend to live in a den, and they make themselves a home where they settle into. And outside of that den, they will pile up sort of the scraps of their food, and we call that a midden.

And so if you’re scuba diving in the wild and you want to find an octopus, a good thing to do is to kind of look in dark, craggy, cave-like places and look for that pile of clam shells, or crab shells, or fish bones, things that they would discard. And that’s a good way to find a camouflaged octopus in the wild.

So because they’re colorblind, how does that work? How do they camouflage? They have a set of cells underneath their skin, pigmented cells, called chromatophores. And they use those chromatophores. They can squeeze pigment in and out in a fraction of a second, and that is what changes their colors.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: And can an octopus know that another octopus is using camouflage? Or are they fooled just as easily as other animals are?

CHRISTINA BIGGS: That’s a good question. I actually don’t know that. I would assume– I mean, some of the several of us are cannibalistic, so they’ll eat others of their own species. So probably the same techniques they use to escape from other predators is what they would use if they encountered another octopus. But I don’t know if we know that.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: So one of the coolest escape techniques is probably ink, and we have a question from an anonymous listener, how do octopuses make ink?

CHRISTINA BIGGS: They have a gland inside their body. It’s an ink sac, and just like you make blood or any type of bodily fluid that you have, a chemical reaction in the body that’s produced by their ink sac gland.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: And the aquarium was closed for a while because of COVID. How did taking care of the cephalopods change when no visitors were there to see them?

CHRISTINA BIGGS: It really didn’t change. We’re essential workers. We came in 365 days as we do every year to provide just the best possible care we can for these animals. I would say just, anecdotally, the octopuses definitely miss having the public to entertain them during the day. So we spent a lot more time offering them enrichment and giving them interesting things to look at and do since they didn’t have that public interaction that they usually get.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: Speaking of entertainment, listener Clara has a question about keeping cephalopods entertained. Go ahead, Clara.

CLARA: Hello. What sort of enrichment do you do for your cephalopods at Monterey Bay Aquarium?

CHRISTINA BIGGS: That’s a great question. We have a lot of things that we do. So we offer them things. I’m sure you’ve seen the videos of octopuses who you can screw them into a bottle and they will work to get themselves out and unscrew bottles. We make puzzle toys out of things like acrylic and plumbing hardware.

We buy dog toys. This is a KONG toy, the kind of thing that you stuffed with treats for your dog. We’ll put food and enrichment items in here for them. We use common things like plastic Easter eggs, puzzle balls. We do things like we have our beautiful kelp forest exhibit on the other side of the building, which they have to regularly trim.

And so we’ll take things like those algaes and throw them in, and they love to interact and play with the algae. Obviously, human interaction– we make skin contact with them every day. They have those amazing chemical receptors in their suckers, and so they can differentiate between humans that come to their exhibits.

We offer them– like I said, we offer them some live food so they have hunting opportunities. There’s just a lot of different things we do. Typically, we do a training session every day with our octopuses. It helps us do things like weigh them, or take them for veterinary care, or make sure that we’re getting them their proper diet. So it’s constant sources of enrichment here.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: And we have a couple questions about eggs. First up is Carrie. Go ahead, Carrie.

CARRIE: Hi, this is Carrie. I was just wondering what the eggs looked like. Are they big or small?

CHRISTINA BIGGS: Yeah, we have all of our eggs– we have four different species here. The first eggs we have here, these are our local market squid eggs. These were collected just off our back deck here, and–

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: Just for the people who can’t see, these look like almost long tubes. is each tube an egg?

CHRISTINA BIGGS: So each tube for these guys, there’s probably about 100 eggs. I like to call them– they’re like fat peapods. They’re long cases, and within that are probably about 100 embryos. Squid, they’re probably about the size of half a grain of rice when they hatch, so a lot of them become food for other animals. And so there have to be thousands upon thousands of them released into the ocean to have a couple that make it into the next generation that’s going to breed and reproduce.

And these animals are really neat. They are pelagic squid, meaning they live their entire lives out in the open ocean. And they make dramatic migrations every night, up and down, in the water column. So they live deeply during the day, and then, at night, they come up to feed on the small plankton that rise each evening.

So these little guys our Pyjama Squid. You’ve seen them. They’re striped. So they tend to lay their eggs underneath rocks and shells. And these are each– as you’re asking, Sophie, these are individuals. So each one of these is just one baby Pyjama squid.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: They’re little white balls. That’s what they look like.

CHRISTINA BIGGS: Yeah, probably no bigger than the size of a pea. And then, if we move down one more, we have these are common cuttlefish eggs. These eggs are black. They’re like about the size of a grape, and their eggs are pigmented with ink. So the female cuttlefish, when she lays the eggs and puts the casing on, she injects into those egg casings. And that’s because she needs to camouflage these really well so that they’re not eaten by predators.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: Just a reminder that I’m Sophie Bushwick, and this is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. We’re celebrating Cephalopod Week with Christina Biggs from the Monterey Bay Aquarium. We also have another question from Greg. Greg, go ahead.

GREG: Hi, my name is Greg. And we were wondering, how do you know what type of cephalopod you get if they’re just eggs when you receive them?

CHRISTINA BIGGS: Oh, that’s a really good question, Greg. So if it’s an egg that we’ve seen before– because we work with so very many of these cephalopods, if it’s an egg that we’ve seen before, we can compare it to pictures we have of other eggs. That’s one way to do it.

Sometimes you just have to wait until they hatch and just see what it is. If they come in– like I said, fishermen sometimes pull things up, and you’re right. You may not know what they are. I would say, based on the knowledge that we have, we can usually make a pretty good guess.

If they’re these long ones that look like peapods, we know that they’re going to be squid. If they’re sort of the round ball ones, we know they’re going to be cuttlefish. And octopuses, octopuses guard their own eggs. And so if we find octopus eggs, it’s going to be with a mother octopus, and she’s going to be taking care of them, and fanning them, and cleaning them, just until they hatch. And then they go on their own way. But that’s how we would know. We would see which kind of octopus those eggs would be with.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: Tricia has a question about the life of an aquarist.

TRICIA: My question was that, since you work so closely with them from birth and your role is their care and enrichment, is it hard not to get attached to them?

CHRISTINA BIGGS: That’s a good question. Definitely, the Giant Pacific Octopus, the one that stays with us the longest, they’re here usually three to five years. Those, definitely, I would say we do become attached to. Some people jokingly ask us, do we name these animals? And I’m like, well, we have probably 400-plus squid on site at any one time, so it’d be impossible to name them.

But some of the bigger octopuses we definitely have a house names for. And yeah, you do. The intelligence of a three-year-old, it’s kind of like my dog is probably the intelligence of a three-year-old, so I compare them. It is like having an animal in your life that you take care of. So yeah, obviously, we care about all the animals. Yeah, definitely.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: That’s all the time we have for now. I’d like to thank my guest, Christina Biggs, senior aquarist at the Monterey Bay Aquarium in Monterey, California. Thank you so much for joining us.

CHRISTINA BIGGS: Oh, thank you, Sophie, for having us. We really love that you guys raise the awareness of these amazing animals that we have the privilege of working with every day. Thanks again for having us.

Copyright © 2022 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Kathleen Davis is a producer and fill-in host at Science Friday, which means she spends her weeks researching, writing, editing, and sometimes talking into a microphone. She’s always eager to talk about freshwater lakes and Coney Island diners.

Sophie Bushwick is senior news editor at New Scientist in New York, New York. Previously, she was a senior editor at Popular Science and technology editor at Scientific American.