Curiosity Rover Discovers Pure Sulfur On Mars

12:11 minutes

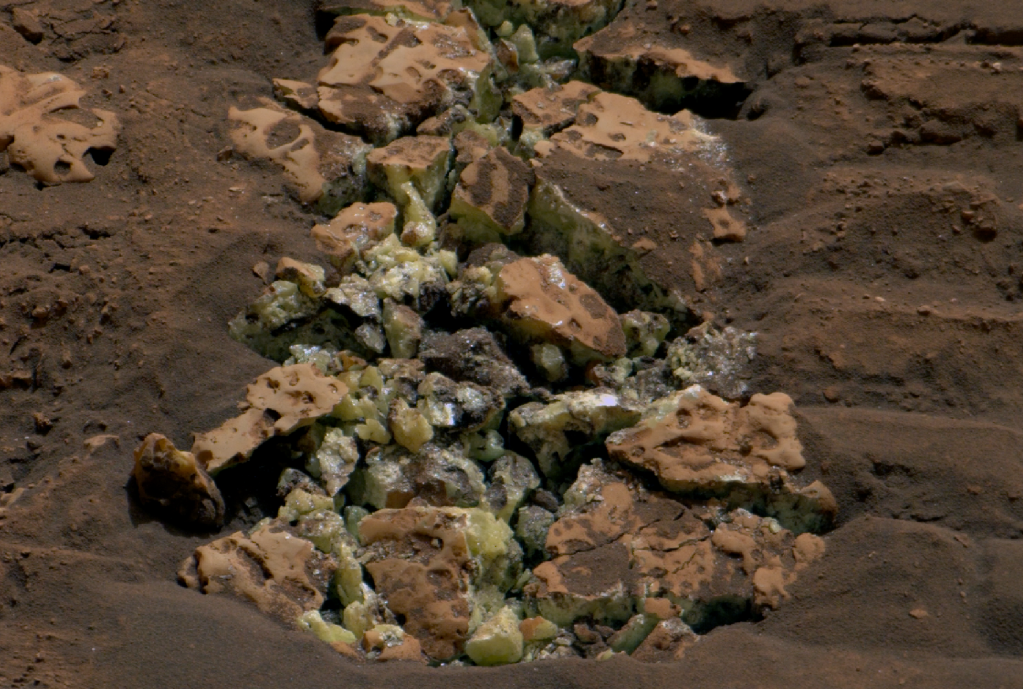

NASA’s Mars Curiosity rover ran over a rock, which cracked open to reveal pure sulfur crystals. This was the first time pure sulfur has been discovered on the planet. The rover found many other similar rocks nearby, raising questions about the geologic history of the location.

Ira talks with Alex Hager, who covers water in the West for KUNC, about Martian sulfur rocks and other top science stories of the week, including melting glaciers increasing the length of the day, life rebounding at Lake Powell, a rare whale and new research on how psilocybin rewires the brain.

Alex Hager is KUNC’s Water in the West reporter and is based in Fort Collins, Colorado.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow, coming to you today from KUNC in Greeley, Colorado. And this hour, we’re featuring research from Colorado-based scientists, including what we can learn about love from rodents– I’m talking about voles– and how a tiny mite is wreaking havoc on honeybee colonies.

But first, this week, there was an unexpected hydrothermal explosion at Yellowstone National Park. That’s a few miles Northwest of Old Faithful geyser in the Biscuit Basin Thermal area. Joining me now to give us the latest on that explosion, plus other top science stories of the week, is Alex Hager, who covers water in the West for KUNC. He’s based in Fort Collins. Welcome back to Science Friday.

ALEX HAGER: Thanks for having me again, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: So what’s going on here with that explosion?

ALEX HAGER: Oh, man. It was really dramatic. If you watch a video of it, it’s this giant plume of steam and rock shooting into the sky and people running away on the boardwalk there. And fortunately, nobody was injured. But it is this really spectacular reminder of just how much heat and force sits under the surface at Yellowstone.

IRA FLATOW: And do we have any idea what caused it?

ALEX HAGER: Well, scientists say the explosion was probably caused by water heating up from some of that underground geothermal activity, and then hitting a clog in that natural plumbing system beneath the surface. And when all that water turns to steam, it’s building a ton of pressure. It needs somewhere to go.

But when it hits that clog, boom. And so in the grand scheme of things, this could have been worse. Thousands of years ago, Yellowstone was seeing similar explosions that made craters more than a mile wide.

IRA FLATOW: Really?

ALEX HAGER: Yeah.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. Because it sits on the top of a dormant volcano.

ALEX HAGER: That’s right. It sits on this big dormant volcano, which that kind of underground activity played a role in heating up the water. But scientists say that, fortunately, it does not seem there have been any big shifts that will be bringing lava spewing from the surface any time soon.

IRA FLATOW: Good to hear that. Now there’s another big surprise. But we’re going to get that one in space from NASA’s Curiosity Mars Rover, which discovered pure sulfur literally by accident on the red planet, right?

ALEX HAGER: Yeah, that’s right. Since late last year, the Curiosity Rover has been rolling around this part of the planet that’s full of salty minerals called sulfates. Scientists think they were left behind by streams and ponds that evaporated billions of years ago. So this week, the Rover was rolling around looking for something interesting, and it rolled right over a rock that broke open. And inside there were these bright yellow crystals of pure sulfur, which have never been seen before on Mars.

IRA FLATOW: Must have surprised scientists just a bit, huh?

ALEX HAGER: It definitely did. It raises a ton of big questions for scientists. Even though they don’t know exactly what it means, there’s one researcher working on the Curiosity Rover who said that finding a whole field of pure sulfur is like, quote, “finding an oasis in the desert.” He said it shouldn’t be there. So now we have to explain it.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. That is really interesting. Back on Earth here, most of us are very familiar with how climate change is melting glaciers and polar ice sheets. But new research shows that this is also making our days slightly longer. How does this work?

ALEX HAGER: Well, the planet is getting hotter. And as a result, a lot of that ice stored at our planet’s poles is melting. So instead of solid water, we have liquid water that can move away from the poles and toward the equator. So we’re kind of shifting the Earth’s center of gravity a little bit. That means the Earth is going to move differently– so much so that it is making the day longer.

IRA FLATOW: How much?

ALEX HAGER: So far, it’s a pretty tiny change. The day’s only getting a little more than a millisecond longer each year. But that is faster than it was before we started to see this 21st century era of climate change.

IRA FLATOW: Does it mean anything important? I mean, it’s nice little factoid. But does it have any ramifications or implications?

ALEX HAGER: To me, this just shows that there are huge, irreparable, wide-reaching problems that are going to keep happening if we don’t hit the brakes on climate change– not just with living things, but with the planet itself. And if climate change gets worse, we keep putting a lot of emissions into the atmosphere, the rate at which the day is getting longer could double.

IRA FLATOW: And could that change how we keep track of time, for example?

ALEX HAGER: Yeah, that’s right. So far, we have been using the rotation of the Earth to calibrate our instruments and timing measurements, and that could be thrown a little out of whack.

IRA FLATOW: For us, it’s really nothing but a couple of milliseconds for timing.

ALEX HAGER: Seriously.

IRA FLATOW: For stuff that travel near the speed of light, that’s a long time. All right, our next story that you brought us is also about climate change. We’ve talked on this show about how Lake Powell is shrinking. But you actually went out on a reporting trip in Glen Canyon to see some of the scientists who were studying the effects of the lake drying up. Tell us what you found, what they’re studying.

ALEX HAGER: Yeah, that’s right. I was just down there last week, actually, baking under the triple-digit desert summer heat. This is what I’m really excited to talk about. Because in a weird way, it’s kind of a positive outcome of climate change.

IRA FLATOW: Really?

ALEX HAGER: Yeah. Lake Powell, it’s the nation’s second largest reservoir, and the levels of water stored in there are dropping. Basically, climate change means less water is flowing in, and people have not been able to rein in their demand.

So we’ve got this supply-demand imbalance. The level of water is going down. That is not great for our ability to have enough water for taps and irrigated farm fields.

IRA FLATOW: Right.

ALEX HAGER: But what it is good for is the plants and animals that live in Glen Canyon– that lived there before the area was put under water.

IRA FLATOW: Oh, so they’re coming back to life again because there’s not that much water to kill them.

ALEX HAGER: Ira, nature is healing. I went to go see it happen in action. I went out with these scientists– Seth Arens and Katie Woodward. They’re doing this research with a nonprofit group called the Glen Canyon Institute, and they’re surveying which plants are coming back.

And they’re finding out that it’s a lot of native plants. They’re going canyon by canyon, taking measurements, and seeing that a lot of plants that were there decades ago in areas that have been under water for decades, are able to take root again. And it’s bringing back these thriving ecosystems.

Even though you’re in the middle of the desert, they’ve got these little creeks running through canyons. They’re full of life. They smell like growth. You can see little frogs jumping around.

IRA FLATOW: Oh, no kidding?

ALEX HAGER: Birds chirping.

IRA FLATOW: You saw all this stuff?

ALEX HAGER: I saw it all with my own two eyes.

IRA FLATOW: And it was surprising to you to be there and see this stuff. Did you get any impression that maybe with the rainfalls that we’re having and the increase in water, that maybe there will be a reversal in the dropping down levels of the lake and bring it back to normal levels the way they used to be?

ALEX HAGER: There has been a little bit of a reversal. But in the grand scheme of things, it’s relatively small. So Lake Powell gets most of its water from melting snow in the Rocky Mountains. In fact, 60% of the water in Lake Powell started as snow right here in the state of Colorado.

IRA FLATOW: Right.

ALEX HAGER: And we had a relatively strong year last year. But at the end of the day, we are in deep. We’re over more than two decades of megadrought, and it is going to take more than one snow a year to turn that around. It’s going to take serious reductions to demand from the cities and farms that use its water.

IRA FLATOW: This next one is a whale of a story– I always have to get that in there– specifically about the spade-toothed whale, which locals found washed up on a beach in New Zealand. I saw pictures of this. Tell us why this is such an extraordinary discovery?

ALEX HAGER: Well, the spade-toothed whale is an incredibly rare species. Just to visualize, it looks a little bit more like probably what you would imagine when you visualize a dolphin than when you think of a whale. It’s about 15-feet long. It’s a type of beaked whale, and they live super deep in the ocean.

We know almost nothing about them. This particular species, the spade-toothed whale, has never been seen alive. Since the 1800s, we’ve only seen hints of this animal six times.

IRA FLATOW: Really?

ALEX HAGER: Little bone fragments, or degraded pieces of a whale’s corpse that were past the point of being able to be studied by scientists.

IRA FLATOW: But this was not a live whale, right?

ALEX HAGER: This was not a live whale, but it was very intact.

IRA FLATOW: And so they got the whole whale that they’ve never seen before. Wow.

ALEX HAGER: Yeah.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. All right, so what’s next for the whale? Obviously, scientists are going to take it apart, or look at it?

ALEX HAGER: Yeah, they’re keeping it in a fridge right now and taking DNA samples, and they sound really excited. One researcher said spade-toothed whales are one of the most poorly known large mammal species of modern times.

IRA FLATOW: What a find. A lot of stories about exciting scientists this week, and stuff we’re finding. And here’s a new study. A new study in the Journal Nature about psilocybin, and it looks at how the drug rewires our brain. Tell us, what did they find?

ALEX HAGER: Yeah, this is a new study in the Journal Nature that shows just how magic mushrooms work on your brain. So we’re talking about psilocybin. That’s the substance in mushrooms that makes you hallucinate.

So scientists did brain scans before, during and after people took a dose, and they found that psilocybin entirely resets some of the neurons in your brain for a short period of time– sometimes a long period of time. And these are the pathways that allow you to have a sense of time and self. And one of the researchers at the Harvard School of Medicine said the changes were so massive that the brains of some of the test subjects resembled the brain of a different person entirely.

IRA FLATOW: No kidding?

ALEX HAGER: Yeah.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. That is amazing. And I imagine this could help researchers better understand how to harness the drug for therapeutic means, right?

ALEX HAGER: That’s right. This opens the door even further for psilocybin use in medicine. It’s been getting a lot of traction as something that could be potentially helpful in therapy for mental health conditions like depression, or post-traumatic stress disorder. So this gives health experts a little more context on how exactly psilocybin impacts the brain and paves the way for more use of magic mushrooms in medicinal use.

IRA FLATOW: We always have to warn our listeners that this is just basic research, and you can’t go out and just ask your doctor for a psilocybin treatment yet.

ALEX HAGER: Yeah, don’t try everything you hear on the radio at home.

IRA FLATOW: All right, speaking of mind bending, our last story is about battery bending. And scientists have created soft, super stretchy jelly batteries?

ALEX HAGER: That’s right. It’s from a team at the University of Cambridge in the UK. And they created these squishy, bendable batteries that were actually inspired by electric eels.

So they can conduct electricity while still being squishable and bendable. And they can be stretched to 10 times their original length without breaking, and then return to their original size. That is thanks to a material called hydrogel, which is more than 60% water.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. Well, I guess if they’re bendable, you could put them on places where batteries need to be bent, right– like clothing, something like that?

ALEX HAGER: That’s right.

IRA FLATOW: Wearables?

ALEX HAGER: That’s right. Yeah, wearable technologies are one of the potential uses for these jelly batteries. But scientists think this could go even further.

These batteries that are soft and tough at the same time, they could someday be implanted in the body. It kind of has some properties of human tissue. So it could be implanted in the brain to help deliver drugs, or treat conditions like epilepsy.

IRA FLATOW: How far off are the jelly batteries from us using them? This is obviously basic, basic, basic research, and we’re not going to see the jelly batteries for quite a while, I imagine.

ALEX HAGER: This seems like it’s in the early stages. I don’t exactly know how far off it is, but it does seem like a promising opening of the door to new batteries that could be used inside your body.

IRA FLATOW: Alex, always good to have you on. Thanks for taking time to be with us today.

ALEX HAGER: Thanks for having me.

IRA FLATOW: Alex Hager, who covers water in the West for KUNC. He’s based in Fort Collins, Colorado.

Copyright © 2024 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Shoshannah Buxbaum is a producer for Science Friday. She’s particularly drawn to stories about health, psychology, and the environment. She’s a proud New Jersey native and will happily share her opinions on why the state is deserving of a little more love.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.