In Wisconsin, Mannequins Help Teach People How To Spot Ticks

5:44 minutes

This article is part of The State of Science, a series featuring science stories from public radio stations across the United States. This story, by Lina Tran, was originally published by WUWM.

Nationwide, Wisconsin is a hot spot for Lyme disease. And cases are rising, as climate change and development alter how humans interact with the ticks that transmit this disease. In Wisconsin, cases reported annually have more than doubled in the last two decades.

With tick season underway, tick checks are one of the most important ways you can prevent infection. I recently visited the Midwest Center of Excellence for Vector-borne Disease, which is housed at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where researchers are using a new tool to teach people how to do tick checks — mannequins.

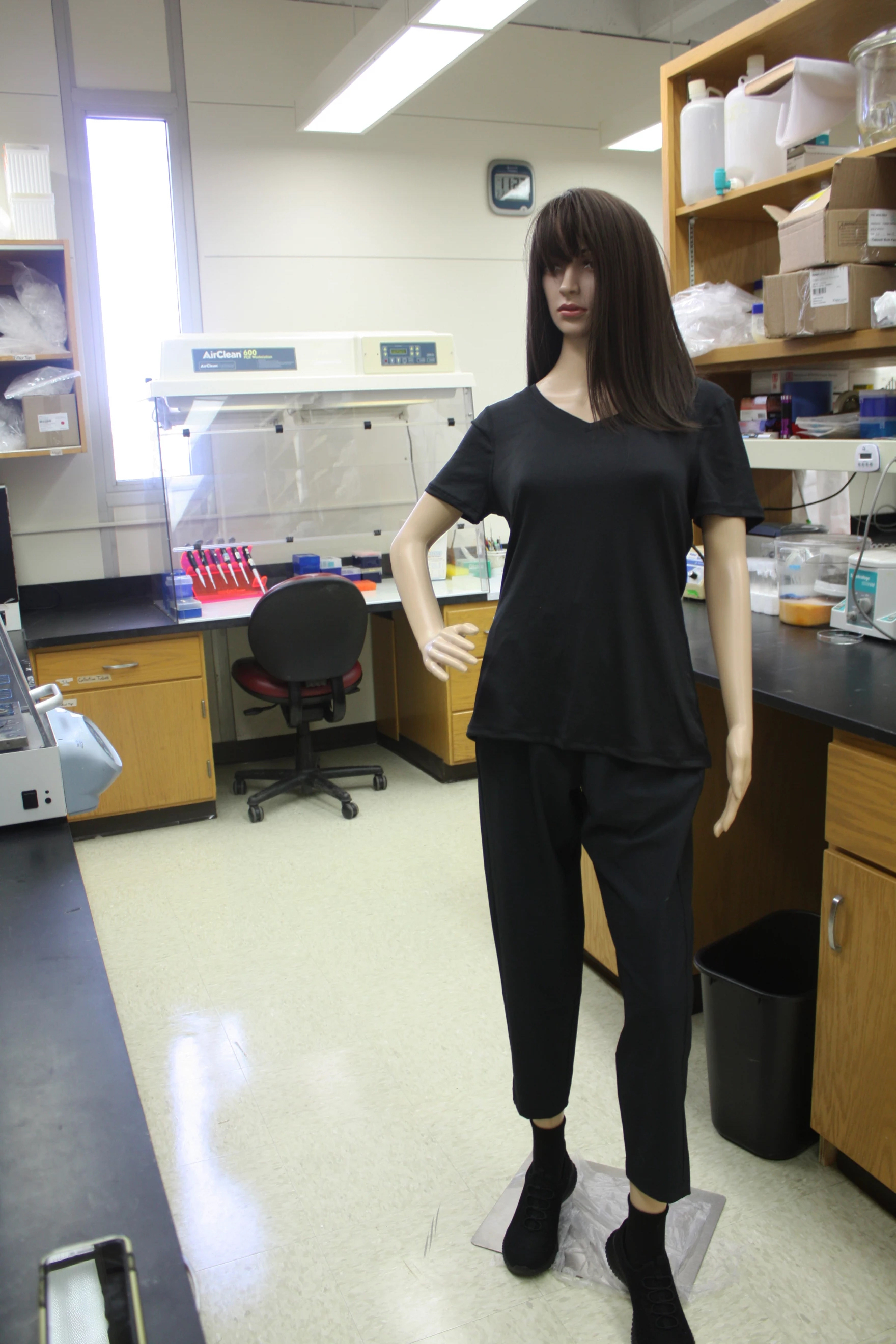

Their names are Vanessa and Valerie. Both are tall brunettes. Both dressed in sportswear. And both are covered in dead blacklegged ticks, also known as deer ticks, the species that carries Lyme.

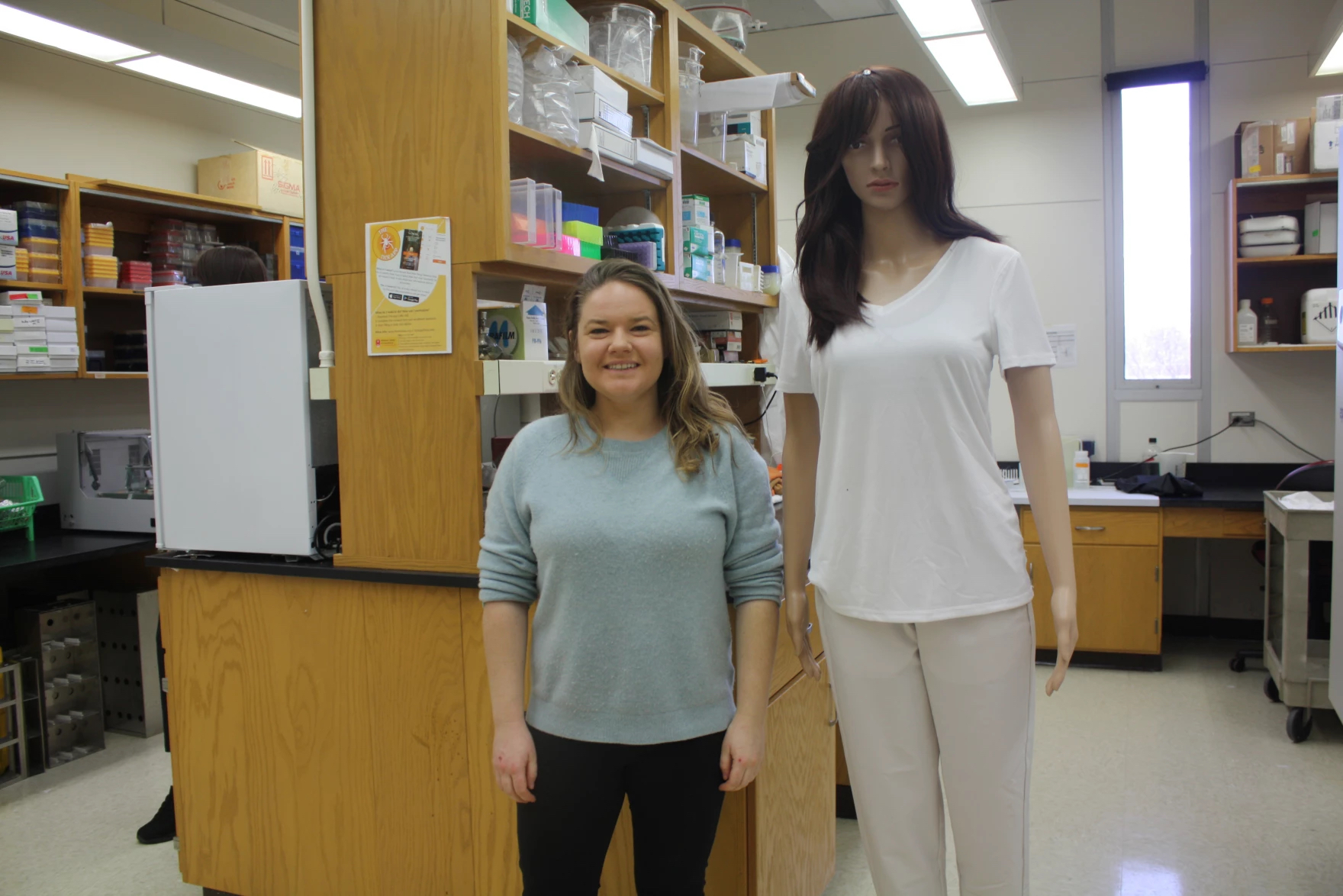

Tela Zembsch is a research specialist at the lab, where scientists are studying ways to control ticks and prevent infection. The lab found the mannequins on Facebook Marketplace, she says. At first, Vanessa was supposed to stand in for a human, in a study on how ticks attach themselves to people. But soon they realized she could be a useful educational tool.

Now, they have a whole family of mannequins.

“We’ve got child mannequins, we’ve got teenagers, we’ve even got pre-teen mannequins,” Zembsch says. “That way, the event that we take it to, it’s set up for who’s going to be looking at the mannequins.”

Ticks are notoriously tough to spot. In 2018, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention tweeted a photo of a poppy seed muffin, explaining five ticks were camouflaged among the seeds and challenging viewers to identify them all. The internet was grossed out; the tweet went viral. Later, the CDC tweeted an apology, saying they didn’t mean to “tick” people off.

Ticks can be the size of a poppy seed. Can you spot all 5 ticks in this photo? Learn how to prevent tick bites. https://t.co/ATtrY7YFoS pic.twitter.com/gBm4tw2qmf

— CDC (@CDCgov) May 4, 2018

But here’s the thing. You’re not very likely to run into ticks on a muffin. So when you’re teaching the public how to spot the tiny arachnids, wouldn’t it be better to show them what ticks look like on a person?

Enter the mannequins. That “was the idea — how to get it in a context people are going to see,” Zembsch says. “They’re not gonna see it in an image, they’re not gonna see it under a microscope lens. They’re probably going to run into a tick on themselves.”

I got an opportunity to test out my own tick-spotting skills.

“Pretend this is your friend,” Zembsch instructs. “She’s just gone hiking and she’s asked you to check her for ticks.”

The two mannequins are nearly identical. Except Vanessa is wearing all-black, from her t-shirt and joggers to her tennis shoes. She also has classic bangs. Valerie keeps her hair in a side part, and she’s dressed in white. Wearing light-colored clothing is an important part of tick prevention; ticks are much harder to detect on dark clothes.

Adult ticks are the biggest and easiest to see. It’s the baby nymphs that you really need to hunt for. Sometimes, it was hard to distinguish a tiny tick from a stray piece of fluff.

Ticks don’t carry the bacteria that causes Lyme on their own. They have to draw blood from wildlife hosts, like deer or mice, first. The bacteria spreads when an infected tick bites another animal — like a human.

When a tick bites you, they can hang on for days. As they feed, they’ll swell, coming close to tripling in size. That’s why it’s important to do a tick check soon after you spend time outdoors. If you find and remove ticks right away, there’s less time for bacteria to spread.

After spending a few minutes with Vanessa, Zembsch walks me over to Valerie, who’s wearing the same outfit as her twin, but in white.

“This was another experiment we did,” Zembsch says. “We wanted to see how black clothing and white clothing would affect [tick checks]. So she’s got the exact same ticks applied to her in the same spots.”

Zembsch says my performance on the test pretty much mirrors what they’ve learned from the demos at public events. People are better at finding ticks on white clothes than black. They’re also better at spotting them on the upper body than the lower body. And, people are much better at catching adult ticks than the young, tiny nymphs.

Zembsch points to one that’s the size of a sesame seed, which I missed on the black pair of tennis shoes. But they’re easy to see on the white shoes.

The researchers are using these results to come up with recommendations for more successful tick checks.

Before she goes on a hike or spends time outdoors, Zembsch tucks her pants into her socks and her shirt into her pants, minimizing skin exposure. She also uses insect repellents like DEET or picaridin.

The best tick checks are thorough and methodical. The CDC recommends paying extra attention under the arms, in and around the ears, inside the belly button, around the hairline, behind the knees, between the legs and around the waist.

“When I’m done with my hike, I start at my feet and I work my way up,” Zembsch says. “I will check every crevice.”

Zembsch recommends asking a friend or family member to check your back. When she’s finished her body check, she also tosses her clothes in the dryer and takes a shower.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Lina Tran is a reporter with WUWM Public Radio in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

ANNIE MINOFF: This is Science Friday. I’m Annie Minoff. Now it’s time to check in on the state of science.

SPEAKER 1: This is–

SPEAKER 2: For WWNO–

SPEAKER 3: St. Louis Public Radio–

SPEAKER 4: Iowa Public Radio news.

ANNIE MINOFF: Local science stories of national significance. So stop me if you’ve heard this one before. Two leggy brunettes walk into a science lab– well, not walk exactly. Vanessa and Valerie are mannequins and their job is to teach us humans how to check for ticks. Ticks, of course, are a well-known summer nuisance in many parts of the country, but climate change is extending their season. Joining me today to talk about this is my guest, Lina Tran, reporter for WUWM, Milwaukee’s NPR. Welcome to Science Friday.

LINA TRAN: Thanks for having me.

ANNIE MINOFF: Of course. So I understand you took a trip to this lab where these two mannequins, Vanessa and Valerie, have become a pretty important educational tool. So explain how mannequins can help us learn to spot ticks.

LINA TRAN: Yeah, OK, so it all starts a few years ago. You might be familiar with this viral tweet from the CDC. They shared this photo of a poppy seed muffin that just went viral and made everyone go crazy.

ANNIE MINOFF: I remember, Lina. I will never forget, but continue.

LINA TRAN: It had five ticks that were camouflaged among the seeds. And the idea was to show people how small ticks can be and just be like, hey, be vigilant. But it’s pretty unlikely that you’re going to run into ticks on a muffin.

ANNIE MINOFF: Yes, thank goodness.

LINA TRAN: Yeah. So I met these researchers at the Midwest Center of Excellence for Vector-Borne Disease. It’s this lab at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. And they’re trying to figure out better ways to teach people how to do tick checks, which are a really important part of preventing tick-borne disease. So they were like, wouldn’t it be better to show people what ticks look like on a person? That’s the idea behind the mannequins. They show you what ticks look like in context and train your eye. So that’s how I met Valerie and Vanessa, two very nice brunette lady mannequins. The scientists glued 16 dead ticks to them and they challenged me to find them all. And, honestly, it was eye-opening. It was not an easy task.

ANNIE MINOFF: How did you do?

LINA TRAN: They said that my results were pretty much on par with the average. So people, on average, were finding seven out of the 16 mannequin ticks.

ANNIE MINOFF: OK, so I hate ticks, just really not a fan, and a big reason is that they are just so hard to spot. They are so tiny. So what did these researchers tell you about how to find these guys more effectively?

LINA TRAN: They are so hard to spot. When I was looking for them, I kept second guessing myself. Is this a piece of fluff or is it an actual tick? So the researchers have been taking the mannequins around to events and they got some information on how you can boost your tick check success rate.

So one thing they learned is dress for success. The researchers had Valerie in all white and Vanessa was in all black. And people are much better at finding ticks on lighter clothes. I actually realized that I have the same black pants as Vanessa. They’re from Target.

ANNIE MINOFF: No way.

LINA TRAN: Yeah, this experience made me want to go back and get the white ones. People are also better at spotting them on their upper body than the lower body, so you should pay special attention to your legs. And then one of the researchers at the lab told me that she tucks her pants into her socks and her shirt into her pants when she’s out, which limits access to your skin.

And then when it’s time for the tick check, be systematic. I was a little chaotic. I was like, ooh, I’m going to look at the armpit and now the knees. But you really should start at the feet and then work your way up.

ANNIE MINOFF: So I used to think of ticks as pretty much exclusively a summer problem, but it feels like I’m finding them all the time now. Is that my imagination or has the tick season actually gotten longer?

LINA TRAN: Ugh, it’s not your imagination. Climate change is causing tick season to start earlier and last longer. Like this year, Wisconsin actually had its warmest winter on record and the state department of health services got their first tick ID request in February, usually people start sending those in late March or early April, so that was a lot earlier.

A doctor here in Milwaukee told me that we need to rethink tick season. So instead of thinking about ticks at a certain time of year, we need to think about them at a certain temperature, which is about 40 degrees. So basically experts told me the rule of thumb is when it’s nice enough that you want to go out, so do the ticks.

ANNIE MINOFF: Great. Great news, Lina. So if you are unlucky enough to find one of these little guys attached to you, what is the best way to remove them?

LINA TRAN: So you want to get some clean tweezers and remove them as soon as possible. You pull the tick up with steady, even pressure. And Tela Zembsch is a research specialist at this lab that I went to. She told me it’s important to get as close as possible to your skin when you’re pulling it. Here’s why.

TELA ZEMBSCH: But you really want to make sure that you don’t do is grab the tick by its body. Because if you do that, you’ll essentially cause them to regurgitate what’s in their stomach into you and that could potentially have pathogens.

ANNIE MINOFF: Lovely, lovely.

LINA TRAN: It’s so disgusting. I’m so sorry. So, yeah, once it’s taken care of, you should keep an eye on it. The CDC says that if you get a rash or a fever within a few weeks of removing a tick, you should see your doctor.

ANNIE MINOFF: All right, wise words. That is all the time we have for now. But I would like to thank my guest, Lina Tran, reporter for WUWM, Milwaukee’s NPR. Thanks for joining us.

LINA TRAN: Thanks for having me.

Copyright © 2024 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Kathleen Davis is a producer and fill-in host at Science Friday, which means she spends her weeks researching, writing, editing, and sometimes talking into a microphone. She’s always eager to talk about freshwater lakes and Coney Island diners.

Annie Minoff is a producer for The Journal from Gimlet Media and the Wall Street Journal, and a former co-host and producer of Undiscovered. She also plays the banjo.