The Maine Lobster Industry Is Entangled With Endangered Whales

4:31 minutes

This segment is part of The State of Science, a series featuring science stories from public radio stations across the United States. A version of this story originally appeared on Maine Public, which is part of the New England News Collaborative: eight public media companies coming together to tell the story of a changing region, with support from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

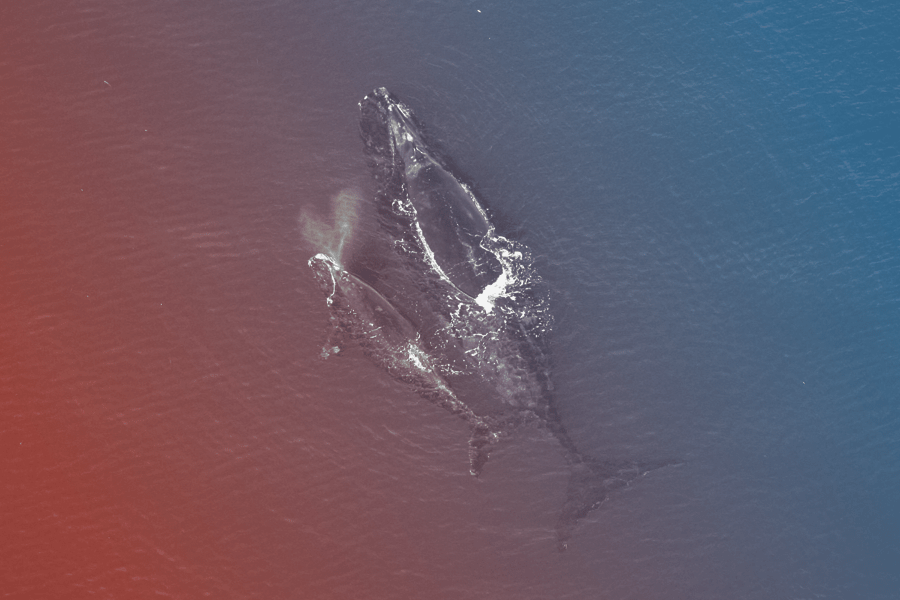

The endangered North Atlantic right whale population took a big hit last year with a record number of animals killed by fishing gear entanglements and ship strikes. Now, an ongoing debate over threats posed by Maine’s lobster industry is gaining new urgency as scientists estimate these whales could become extinct in just 20 years.

Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution scientist Mark Baumgartner says that to help the whales survive, the rope Maine lobstermen use to mark their traps with buoys and haul up their catch must be modified or even eliminated. And it’s not just for the whales’ sake.

“I feel the industry is in jeopardy,” Baumgartner says.

Baumgartner was in Maine this month for a Lobstermen’s Association meeting to detail the whales’ plight. If the lobster industry doesn’t respond effectively, he says, the federal government will step in. “As the population continues to decline and pressure is put on the government to do something about it, then they’re going to turn to closures, because that’s all they’ll have,” he says. And that could mean barring traps in the same waterways the lobster fishermen count on for their livelihoods.

There were about 450 North Atlantic right whales estimated to be alive in 2016. Only five calves were born last year, while there were 17 deaths caused by rope and gear entanglement or ship strikes. Baumgartner says with no new births and another death already this year, the trend line is tipping toward the whale’s effective extinction within 20 years.

“I feel the [lobster] industry is in jeopardy.”

But, his warnings are getting a somewhat frosty reception from Maine lobstermen, who feel they’re being singled out for a problem that crosses state and even national boundaries.

“There was a lot of deaths on the right whales this year, but none in the Gulf of Maine,” says Bob Williams, who has been hauling traps off Stonington, Maine, for more than 60 years.

[Because we know you’ve always wondered what would happen if you threw a frisbee on Mars.]

None of the dead whales were found near Maine’s coast. But three were found off Cape Cod, which is part of the Gulf of Maine—where Baumgartner uses passive recording devices to help track their movements.

Parts of Massachusetts’ already diminished lobster fishery in recent years has been closed during the height of the right whales’ migration.

Williams, the lobsterman from Maine, says the industry here has stepped up, too, adopting expensive gear required by regulators. Now scientists are proposing new modifications, such as weaker ropes or even rope-less technology that relies on radio signals to locate traps. But Williams says those are likely unworkable off Maine.

“Because we have heavy tides and all that, and the farther east you go down towards eastern Maine, [there are] extreme tides down there,” he says. Lobster trappers need to use ropes there, but the whales get tangled in ropes and lobster buoys, slowing them down and forcing them to burn more calories just to swim.

Many fingers in Maine are pointing the blame at Canada.

“Canada needs to step up,” says Patrick Kelliher, commissioner of Maine’s Department of Marine Resources.

He says that while the Gulf of Maine is a known part of the whales’ territory, their paths lie mostly far off Maine’s coast. Meanwhile, Canada’s Gulf of St. Lawrence has suddenly become a killing ground. “With what’s going on in the Gulf of St. Lawrence right now with the Canadian crab fishery, that’s where most of that gear is. If you looked at the diameter of that rope, that’s not Maine fishing gear,” he says. Maine’s lobster gear is lighter and thinner than the gear designed to catch snow crab.

In fact, most of the whales found dead last year did turn up in Canada’s Gulf of St. Lawrence, rather than U.S. waters.

[Peeling an egg for breakfast? Let’s crack the code on easy-to-peel, hard-boiled eggs.]

The whales could be ranging more widely, following the ebb and flow of their traditional food sources, or looking for new ones. Their staple is a tiny crustacean called Calanus finmarchicus, whose abundance changes with the currents and the climate.

Erin Meyer-Gutbrod, a marine scientist at the University of California, Santa Barbara, says migration appears to be changing. “The reason whales died last year is because they were utilizing relatively new habitats, where there’s no protective legislation in place,” she says.

“They’re facing waters that aren’t protected by vessel speed reductions, fishing gear regulations, seasonal fishery closures. They don’t have any of those protections because we didn’t realize they were going to be there,” she says.

Earlier this year, the Canadian government did impose new requirements that would be familiar to U.S. lobstermen, like strictures on floating rope and mandatory reporting of lost gear. And late last month, Canada Department of Fisheries and Oceans biologist Matthew Harding floated a new idea to skeptical fishermen in New Brunswick’s growing snow crab industry.

He told a CBC reporter that the government could shut down a large swathe of the fishery when whales might be present, or it could take more dynamic action. “Which would be smaller, temporary closures that could be more mobile and more tailored and specific to certain areas,” Harding says.

“[Whales are] facing waters that aren’t protected by vessel speed reductions, fishing gear regulations, seasonal fishery closures. They don’t have any of those protections because we didn’t realize they were going to be there.”

Similar strategies are being explored in the U.S. But there may not be much time. Last month the New England-based Conservation Law Foundation (CLF) filed a federal lawsuit against the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration for violating the Endangered Species Act.

CLF says the federal government is failing to regulate Maine’s lobster fishery in a way that protects the whale from extinction. CLF Lawyer Emily Green says it’s a vital issue for the organization’s members.

“The majesty of this incredible species that they’ve been able to experience—those are moments these people really treasure,” she says. “They would experience it as a personal loss, if they knew that was something they could never experience again because in their lifetime their own government had failed to protect the preservation of the species.”

Stakeholders in both countries are working to prop up the struggling species without sinking the lobster and crab industries. But the question now is whether legal action could hasten new fishery closures, and whether that would do enough to save the whales.

Fred Bever is a reporter at the New England News Collaborative and Maine Public Radio News in Portland, Maine.

IRA FLATOW: And now it’s time to check in on the state of science.

SPEAKER 1: This is [? KERA. ?]

SPEAKER 2: For WWNO–

SPEAKER 3: St. Louis Public Radio.

SPEAKER 4: Iowa Public Radio News.

IRA FLATOW: Local science stories of national importance– the North Atlantic right whale is endangered. Scientists estimate a population of about 450 individuals. No new calves were born this year, and last year, 17 right whales were killed by boat strikes or fishing gear entanglement.

In the state of Maine, one of the states in the whales’ range, this has set off a big debate inside one of its iconic industries, lobster fishing, and what role lobster traps might play in these deaths. Fred Bever is here to tell us that story. He’s a reporter with Maine Public Radio News and the New England News Collaborative. Fred, welcome to Science Friday.

FRED BEVER: Hi, John.

IRA FLATOW: So first of all, how does the lobster industry play a part in the troubles of the right whales, and how big of a problem is it right now?

FRED BEVER: Well, so lobster traps go in the water. The lobstermen keep track of them from buoys that are tied to them by ropes that go down to the bottom. Sometimes one trap is linked to another by rope. And all off the coast of Maine, you see these buoys floating around, and under every one is a rope.

For a right whale, which is as big as a school bus when it’s fully mature– and a fully mature school bus, a big one, can weigh 50 tons– it’s a maze. Now, the whales tend to stay farther offshore than inshore. And that’s a big part of the question right now. How many of these lobster trap ropes and buoys are actually where the whales travel?

But there is strong evidence of entanglements by fishing gear. It’s hard to say what fishing gear, but some scientists estimate from photographic evidence that as much as 85% of those surviving right whales– as you mentioned, there are only 450 left– as many as 85% of them have either been entangled or are entangled. And those ropes, they can cut to the bone. They can cut flesh. They can slow the whales down, make it harder for them to get around, to feed, to get the nutrition they need, and eventually starve. So the stakes are high.

IRA FLATOW: What are the current regulations in Maine on the lobster industry to try and protect the whales?

FRED BEVER: Well, most of the regulation of the lobster industry that takes place in Maine is about protecting the lobster and the lobster stock and making sure that it’s healthy and not overfished. It’s the federal government, really, that’s doing the regulation on the whales, and that regulation goes from southern Florida to the Canadian border, which the whales range all across there. So the feds back in, I think, around 2010, said, OK, lobstermen, the rope that you use to tie one trap to another– the ground lines, they’re called– they used to be made out of rope that sort of floated. And it would arc into the water. Well, that’s a potential hazard for the whales.

So they said, you got to sink that rope. OK, you have to use rope that sinks and doesn’t float up into the water column. More recently, they’ve required new marking requirements on the ropes to try to help them identify if they find an entangled whaled who’s hurt or dead, maybe help them to find out where it’s from. Rope degrades over time, so it’s a difficult task.

They’ve also forced boats to slow down when they’re in whale migration lanes, and boats that are fishing more in those whale lanes, they’re making them put more traps on a single vertical rope to a single buoy, again, trying to reduce the amount of rope that’s in the water. By some estimates since 2010, about 25,000 miles of rope, of floating rope, have come out of the water. There’s that much less out there.

IRA FLATOW: Well, I just have to cut in, Fred, because you just have about 30 seconds. I assume that the lobster industry is pretty worried about this.

FRED BEVER: Yes, the lobster industry is worried about it. There’s some skepticism that the whales really are interacting. There’s more research going on around that. Meantime, environmentalists are bringing a federal lawsuit under the Endangered Species Act trying to get the federal government to act and act quickly and to impose new regulations, maybe even ropeless means of tracking your traps.

IRA FLATOW: Well, we’ll be following that, both the right whale and the lobster industry. Fred Bever with Maine Public Radio News and the New England News Collaborative, thanks so much, Fred.

FRED BEVER: Thank you, John.

Copyright © 2018 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Alexa Lim was a senior producer for Science Friday. Her favorite stories involve space, sound, and strange animal discoveries.