An Oregon Lithium Deposit Could Help Power Clean Energy Tech

8:15 minutes

This article is part of The State of Science, a series featuring science stories from public radio stations across the United States. This story, by Bradley W. Parks, was originally published on Oregon Public Broadcasting.

This article is part of The State of Science, a series featuring science stories from public radio stations across the United States. This story, by Bradley W. Parks, was originally published on Oregon Public Broadcasting.

President Joe Biden and U.S. lawmakers are ramping up their efforts to mine, manufacture and process more battery materials at home — and that’s drawn praise from the company exploring a large lithium deposit in southeast Oregon.

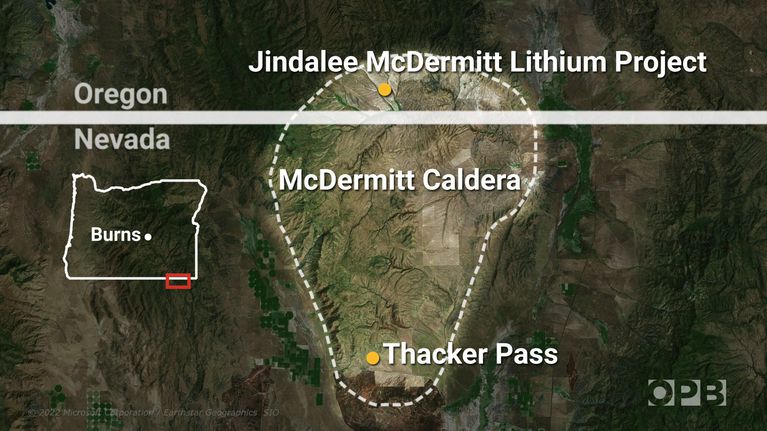

Jindalee Resources Limited, the Australian company with lithium claims at a Bureau of Land Management site in Oregon’s Malheur County, says the growing push for U.S. critical minerals production is a positive sign.

“You’ve seen bipartisan support for the development of critical minerals projects growing,” said Lindsay Dudfield, Jindalee’s executive director. “Jindalee is advancing a critical minerals project, and so we’re very encouraged by these developments.”

The Intercept reported Thursday that Biden is preparing to invoke the Defense Production Act to expedite production of batteries for electric vehicles, consumer electronics and renewable energy storage.

The Defense Production Act was recently used to increase supply and hasten delivery of COVID-19 vaccines. Lawmakers in recent weeks have urged the president to use his authority under the law to do the same for batteries.

“The time is now to grow, support, and encourage investment in the domestic production of graphite, manganese, cobalt, lithium, nickel, and other critical minerals to ensure we support our national security, and to fulfill our need for lithium-ion batteries — both for consumers and for the Department of Defense,” wrote Sens. Lisa Murkowski, R-Alaska; Joe Manchin,D-W.Va.; Jim Risch, R-Idaho; and Bill Cassidy, R-La., in a letter to the president last week.

The Biden administration published a report last June that found the American battery supply chain to be extremely vulnerable as demand for batteries increases. For decades, the U.S. has relied on foreign imports of minerals needed to make those batteries, especially lithium.

While the U.S. has large lithium reserves, it only produces about 1% of the world’s supply. Demand for lithium and other materials is expected to skyrocket as the U.S. seeks to transition away from fossil fuels, according to the International Energy Agency.

The Biden administration’s report says lithium could be a good candidate for new domestic mining and extraction, which would reduce American dependence on foreign sources like Russia and China.

But as the rush for critical minerals like lithium speeds up in the U.S., environmental groups, Native American tribes and others have urged caution, especially when it comes to new mining. The extractive industry remains enormously destructive to frontline communities as well as land, water and wildlife.

John Hadder, director of the mining watchdog group Great Basin Resource Watch, said it’s important not to ignore the effects of mining because the end use of the materials — in this case, batteries — is popular.

“These mine projects are very damaging,” he said. “And so we must approach them judiciously and not in a rushed fashion. In our view, the fewer mines that we develop, the better.”

Hadder added that the desire to extract more lithium and other materials in the U.S. is based on soaring demand projections that may never materialize. He said policy changes and more robust battery recycling would likely reduce the need for extracting new materials.

Biden has said he can only get behind new mining if companies adhere to rigorous environmental and labor regulations.

“Environmental protections are paramount,” Biden said at a White House event to address the American mineral supply in February. “We have to ensure that these resources actually benefit folks in the communities where they live, not just shareholders.”

Biden also announced at that event the formation of a working group to make changes to the General Mining Law of 1872, which still governs mining and speculation on public lands.

The Jindalee project west of the Oregon-Nevada border town of McDermitt is still in the exploration phase, and no mine has been proposed.

The company is in the midst of a drilling program to determine how much lithium is deposited at the project site and whether it is economically viable. Jindalee says the deposit could eventually support a mine, but Dudfield estimates a mining proposal is years away at the earliest.

“We’re a long way from mining, I have to stress that,” Dudfield said. “There’s a lot of work to be done, and we may never get to the position where we are able to mine the project.”

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Bradley Parks is an environment reporter at Oregon Public Broadcasting in Bend, Oregon.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. And now it’s time to check in on the state of science.

[OVERLAPPING VOICES] This is KERA– for WWO– St. Louis Public Radio– Iowa Public Radio news–

IRA FLATOW: Local science stories of national significance– Southeast Oregon is home to a large lithium deposit. Lithium is the lightest metal on the periodic table. Since its highly reactive, it’s used in batteries for electric vehicles and renewable energy storage.

Interest in Oregon’s lithium deposit is likely to grow. This week, President Biden invoked the Defense Production Act to ramp up the mineral supply chain at home. This is an effort to stop relying on countries like Russia and China for vital green energy minerals.

How could this play out in Oregon? Joining me today to help us break it down is Bradley Parks, Environment Reporter for Oregon Public Broadcasting based in Bend, Oregon. Welcome to Science Friday.

BRADLEY PARKS: Hello, Ira. Thanks for having me.

IRA FLATOW: Quite welcome. So can you give us an idea of just how big this lithium deposit is?

BRADLEY PARKS: Sure, so it’s kind of complicated. But the initial estimates from the company put it at around 1.4 billion tons of material. That’s the estimated mineral resource is what they call it. And that would create about 10.1 million tons of lithium carbonate equivalent.

Like I said, it’s kind of complicated how much lithium that actually is. But those are the numbers that we have.

IRA FLATOW: But that translates to a lot of batteries, right?

BRADLEY PARKS: Right, exactly.

IRA FLATOW: And tell us about the ecosystem where this deposit sits.

BRADLEY PARKS: Sure, so this is part of what’s known as the sagebrush sea. It’s a big swath of land that runs across the American West. And it’s home to creatures like sage-grouse, golden eagles. Lahontan cutthroat trout are important in the waterways there, pronghorn, some of the fastest land mammals in North America.

And that ecosystem has declined by as much as half in the past century. So it’s kind of a vital resource. And this particular location is part of what’s known as a sagebrush focal area. So it’s a label that the federal government used to designate the best of the best sagebrush habitat left.

IRA FLATOW: So I would imagine in this extraction project there has been pushback against mining lithium at this site.

BRADLEY PARKS: Right. So the biggest threats to the sagebrush sea are habitat fragmentation. And that’s what’s gradually whittled it away over time. And people are still worried about that now.

IRA FLATOW: Now, I understand that an Australian company has claims to the lithium on this land. So what kind of work is being done there now?

BRADLEY PARKS: Right, so they’re in the exploration phase, so basically looking to see exactly how much lithium is out there. That estimate is exactly what it sounds like. It’s just an estimate.

And so what they’re doing is they’re in the midst of a multi-year drilling campaign to sort of see exactly how much is out there. And by increasing confidence in their estimate, they’re able to attract investors and make money for themselves. And so that process takes many, many years or many rounds of permitting and regulatory review that are involved.

And so I spoke with the executive director of Jindalee Resources, the Australian company, Lindsay Dudfield. And he said that there are still years between now and potentially mining this project.

LINDSAY DUDFIELD: There’s a lot of work to be done. And we may never get to the position where we are able to mine the project.

IRA FLATOW: So as you say, this is not going to be happening any time soon. Any sense of a ballpark timeline?

BRADLEY PARKS: Right, so with all of the drilling that still has to be done for the exploration as well as like pre-feasibility studies on a mine, environmental impact, National Environmental Policy Act review, they estimate still five years away from even having a mining pitch to be reviewed.

So still quite a while, but it’s also worth noting that political support at the federal level is ramping up. And that’s good news for people who are in the critical minerals business.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, because as I mentioned earlier, the Defense Production Act will bolster the manufacturing of items including electric car batteries. And of course, that would have an impact on the lithium in Oregon I would expect.

BRADLEY PARKS: Exactly, and not just in Oregon, but in other places that we know that lithium exists in the United States, particularly in Nevada, the Carolinas as well, anywhere that has a lithium deposit. If we know it’s there, we can only mine lithium where we know it exists. And so those communities are going to be the ones faced with this debate.

IRA FLATOW: And I imagine, as you mentioned before, they’ll have to be balancing the impact on the environment with the process of mining the ore.

BRADLEY PARKS: Exactly, so there are a number of things to take into consideration. Thea Riofrancos is an Associate Professor at Providence College, and is an expert on lithium extraction, and has studied it in Latin America where mining is much bigger industry than in the United States. And she had this to say.

THEA RIOFRANCOS: We’re looking at a very invasive economic sector that is among the most environmentally disruptive in the world. And we should be thinking about what an energy transition would look like that attempted to reduce how much resource is needed to come out of the ground, with the knowledge that some do for sure.

But can we try to avoid as much new mining as possible? And what would that look like?

BRADLEY PARKS: So there’s this acknowledgment that we do need some lithium to make batteries for electric cars and to store renewable energy sources like wind and solar. But lithium itself is a non-renewable resource. We only have what we have.

And so I guess opponents to this are focused on how can we achieve the same goals of energy storage, and powering electric vehicles, and consumer electronics like that, through things like recycling and focusing our electrification on larger sectors like transit.

But while the political pressure is sort of ramping up with the Defense Production Act, that process is moving pretty fast. But the process of actually exploring and mining deposits like this still takes a long time, like we mentioned earlier.

And so now is the time to have those conversations about whether we want to dig this up and sacrifice the land that sits on top of it. We have to have those conversations while the material is still in the ground.

IRA FLATOW: This had to be on the radar screen in the past at some time. Do you feel that this has moved to the front burner with all the political issues that are going on now that made it more urgent?

BRADLEY PARKS: Yeah, there’s sort of been a slow build up to this rush for critical minerals in the United States. So the US produces around 1% of the global supply of lithium. But there have been a number of factors that have played into getting where we are today.

So there was the trade war with China. China is obviously big in the refinery and production of battery materials. And so that trade war sort of primed us for where we are now. Announcements by companies like General Motors and other automakers who say we’re going all electric, those are not empty claims.

And they require a lot of materials, not just lithium, but cobalt, and nickel, and copper, and other things that are used in batteries. That’s another element of this. And then the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Russia is a critical minerals powerhouse. And Ukraine also has large lithium deposits.

So the war in Ukraine has also had its effect on the global supply of critical minerals. What that means for frontline communities is if you have lithium, there’s about to be a process playing out to possibly pull that out of the ground. And like I said before, now is the time to have the conversation while it’s still in there.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, good perspective on this, Bradley. Thank you for taking time to be with us today.

BRADLEY PARKS: Thank you, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: Bradley Parks, Environment Reporter for Oregon Public Broadcasting based in Bend, Oregon.

Copyright © 2022 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Kathleen Davis is a producer and fill-in host at Science Friday, which means she spends her weeks researching, writing, editing, and sometimes talking into a microphone. She’s always eager to talk about freshwater lakes and Coney Island diners.

John Dankosky works with the radio team to create our weekly show, and is helping to build our State of Science Reporting Network. He’s also been a long-time guest host on Science Friday. He and his wife have three cats, thousands of bees, and a yoga studio in the sleepy Northwest hills of Connecticut.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.