New Jersey’s Lenape Nation Fights Ford’s Toxic Legacy

10:24 minutes

This article is part of The State of Science, a series featuring science stories from public radio stations across the United States. This story, by Michael Sol Warren and Andrew S. Lewis, as a part of the podcast Hazard NJ, was originally published by NJ Spotlight News.

The Turtle Clan of the Ramapough Lenape Nation has lived in the wooded hills around Ringwood for centuries, enduring the impacts of European settlement and the building up of America.

But the toxic waste that now surrounds the Passaic County community is from an invasion of an entirely different kind.

And it wasn’t long before residents started getting sick.

When the federal government created the National Priorities List, better known as Superfund, in 1980, abandoned iron mines in Ringwood were among the first sites to be listed; they made the list in 1983. Between 1965 and 1974, the Ford Motor Company dumped hundreds of thousands of gallons of paint sludge, solvents and other waste into the mines scattered throughout the Turtle Clan’s homeland.

By then, the southern portion of the site had been sold off by Ford to the Ringwood Solid Waste Management Authority, which went on dumping more waste onto and into the already toxic land. Arsenic and lead, benzene and 1,4-dioxane leached into groundwater. Kids played among slabs of hardened paint sludge. Adults scavenged the dump sites for copper and other valuable metals.

Valerie Gunn: ‘After that it was like everybody started getting cancer.’

Cancer and other severe health problems began to soar. One street — Van Dunk Lane — is known to locals as “Cancer Row” because every household on it has been touched by the disease in some way.

The trouble on Van Dunk Lane began in the late 1990s when 10-year-old Collin Milligan was diagnosed with Ewing sarcoma, a rare cancer that affects the bones and the soft tissue around them. According to Valerie Gunn, the boy’s aunt and a longtime Upper Ringwood resident, Milligan only lived for a year after his diagnosis.

“After that,” Gunn said. “It was like everybody started getting cancer.”

While there may no longer be a risk of more dumping, another threat looms over the Upper Ringwood community.

As global warming changes the climate worldwide, New Jersey is facing increasingly intense rainfall events, like last year’s Tropical Storm Ida, as well as periods of extreme heat and drought. Advocates, environmental experts and government officials are raising concerns that the pollution contained in the state’s Superfund sites like Ringwood could be released in ways they haven’t been before. With 114 sites on the Superfund list — the most in the U.S. — New Jersey stands to bear these new threats more than any other state.

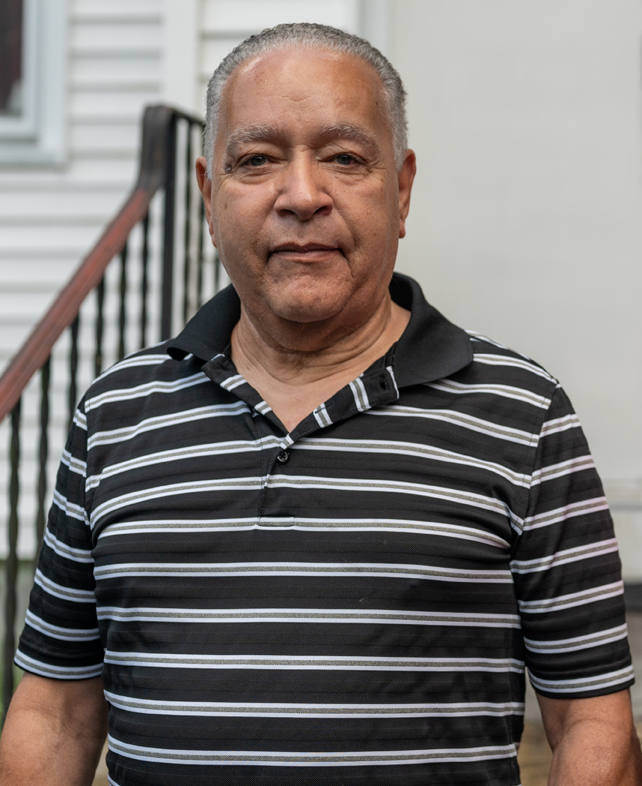

Wayne Mann, a fellow Ramapough Lenape Nation member, remembered Collin Milligan’s death as a wake-up call for the community that something was not right with the land.

“Collin was one of the main wills that gave me a reason to fight and fight hard, because he was just a little kid,” Mann said. “He woke me up fully.”

Mann, who has been diagnosed with cancer and suffers a variety of other ailments, was the named plaintiff in the case Mann v. Ford, in which roughly 600 Upper Ringwood residents sued Ford and other defendants in state court seeking to collect damages for the impact of the dumping. The case was settled out of court in 2009, with the residents splitting about $10 million. A HBO documentary about the case was released in 2011; dozens of community members died during the time it was being filmed.

“I dug my heels in and didn’t care about the price I paid,” Mann continued. “Because Collin already paid the ultimate price.”

Dennis DeFreese: ‘The boys used to tell me when they shot a deer, it would have these big bubbles and like tumors inside of it.’

Gunn and Mann’s neighbor and fellow Lenape Nation member, Dennis DeFreese said the illnesses extended beyond Upper Ringwood’s human community.

“The boys used to tell me when they shot a deer, it would have these big bubbles and like tumors inside of it,” DeFreese said. “Something’s radically wrong.”

After Ford removed 7,000 cubic yards of paint sludge and contaminated soil, along with 60 drums of more waste, the site was removed from the Superfund list in 1994. But when more toxic materials were discovered — and after an exposé by The Record spurred heavy political pressure — it was relisted in 2006. Of the 1,781 sites that have been toxic enough to be included in the Superfund program, the “Ringwood Mines/Landfill,” as it is officially called by the Environmental Protection Agency, is the only one that has been relisted.

Ford did not answer specific questions submitted by NJ Spotlight News, but in a statement said it is working cooperatively with regulators on the site’s cleanup.

“Ford Motor Company takes its environmental responsibility seriously and has shown through its actions a commitment to addressing the issues in Upper Ringwood that are related to Ford,” a Ford spokesperson said.

On Thursday, New Jersey officials announced a lawsuit demanding damages from Ford, not just to recoup the costs of cleaning the land, water and air around the dumping site but also for the harm its pollution caused the community.

New Jersey has recently begun to focus on the environmental and social damage done by industrial pollution in what are known as environmental justice communities, frequently poor and largely communities of color.

“Whenever you look at any kind of marginalized or underserved community, be it the Ramapough Nation or other Native American or marginalized communities, they are going to get hit the hardest,” said Judith Zelikoff, a professor in New York University’s Department of Environmental Medicine. Zelikoff has studied the health impacts of the Ringwood Superfund site on borough residents who live near it and on top of it — most of whom are Turtle Clan members.

“They experience cumulative environmental exposures including poor food, water, and air quality, which could exacerbate pre-existing health disparities associated with low socioeconomic status,” then-doctoral candidate Gabriella Meltzer wrote in a paper she co-authored with Zelikoff and colleagues at NYU in 2020.

Between December 2015 and October 2016, Meltzer, Zelikoff and a team of four NYU graduate students conducted a survey of 187 members of the Turtle Clan and non-Native Americans in Ringwood, half of whom were living on or near the Superfund site, in an effort to identify a pattern of chronic health issues.

Such a study had never been done before. The researchers identified elevated levels of asthma, allergies, arthritis, heart disease, and high blood pressure in people who had reported multiple exposures to the Superfund site. The levels increased when the survey was limited to Native American residents, who were found to be 13.84 times more likely to face exposure than non-Native Ringwood residents.

The authors pointed out that their findings were consistent with those in studies of other communities of color, particularly Native Americans. Over 400,000 Native Americans in the U.S., they added, live within three miles of a contaminated area or Superfund site.

In addition to Turtle Clan children and adults playing on and scavenging the dump site, many of them ended up living on top of it after Ford sold a portion of the land, which was then used to build affordable housing. “They’re already being hit on so many levels,” Zelikoff said. “Then you add a second stressor, which are climate change alterations like drought and excessively high heat, and you’re adding fuel to the fire.”

Larger and more persistent wildfires are proving to heighten health risks for communities everywhere, even if those wildfires are thousands of miles away. Last summer, skies throughout the Northeast became hazy from the more than 1 million acres of land that was burning on the West Coast and in Canada.

“A lot of that air pollution is particulate matter, which is associated with exacerbation of asthma and, in some cases, induction of new asthma,” said Zelikoff. “It’s also associated with lung cancer.”

While Turtle Clan members once had hoped to remain on their homeland in Upper Ringwood, the years of inadequate cleanup and elevated health problems have led to a slow draining of the community. Where there were once about 100 homes and 1,000 residents, there are now 50 homes inhabited by 300 people.

With little hope of seeing the land completely cleaned up — the EPA has sought to “remediate” still-contaminated land by covering it with solid or earthen caps, as well as remediating contaminated groundwater — the Turtle Clan’s chief, Vincent Mann, is now hoping that Ford and the EPA will pay for the relocation of the remaining residents in Upper Ringwood.

In May, Chief Mann and other representatives of the Turtle Clan met at the EPA office in Edison with Lisa Garcia, the regional administrator of EPA Region 2, and other EPA officials to talk through the relocation proposal. Officials from the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection and New Jersey Department of State, as well as U.S. Reps. Frank Pallone (D-6th) and Josh Gottheimer (D-5th), also attended.

Walter Mugdan: ‘Relocation is considered an extraordinary remedy.’

A presentation shared at the meeting lays out what the Ramapough delegation pitched: Chief Mann wants the residents of Upper Ringwood to be permanently relocated into 100 new homes, to be built on the nearby Tranquility Ridge county park. According to the presentation obtained by NJ Spotlight News, he expects this would cost at least $50 million. Additionally, a decision on the allocation of the Tranquility Ridge plot to the Turtle Clan would have to be made by both the Legislature and the DEP, because the land is preserved under the state’s Green Acres open space program.

Speaking with NJ Spotlight News days after meeting with the Ramapough delegation, Garcia said the EPA would at least reassess the remediation plans for the Ringwood Mines site, to reconsider if relocation is warranted.

“We had made the promise that we would go back and certainly look at their requests and work with the state and some of the elected officials to see what options there are,” Garcia said.

The Superfund law explicitly allows temporary or permanent relocation of people living on or near Superfund sites as part of cleanup plans. But the provision is rarely used, according to Walter Mugdan, the EPA’s deputy regional administrator for Region 2.

“Relocation is considered an extraordinary remedy,” Mugdan said. “And one that is considered to be appropriate when there’s an immediate threat to residents that can’t be addressed through other less intrusive means.”

But Chief Mann, speaking with NJ Spotlight News again Thursday, said even a commitment from EPA to reconsider the relocation option is a positive sign.

“I think that they see the light,” Chief Mann said. “That our legal team provided an incredible PowerPoint presentation that just spoke the truth. And I think that when those people … who were sitting there with us and felt the emotion of the testimony that was being given, that they also understood that. That they probably went back to understanding why they became involved in environmental justices.”

In the first attempt at remediation in the ’80s and ’90s, and in the second now underway, the EPA has not determined relocation has been needed in Upper Ringwood to protect public health.

Of the more than 1,700 sites nationwide that have been placed on the Superfund list, relocation happened in 33 of them, according to the EPA. Temporary relocation was used in two-thirds of those cases, like when families from well-off Essex County towns were displaced during the cleanup of the Glen Ridge Radium and Montclair/West Orange Radium sites.

Permanent relocation has been used just 11 times for Superfund sites. One of those was in Hoboken, at the Grand Street Mercury site, where an industrial building was being converted into luxury apartments before liquid mercury was found to be seeping through the floors.

“Literally liquid mercury was found when they were doing reconstruction. It was found in the walls, it was dripping down to the ceilings, it was in the closets falling onto people,” Mugdan of EPA’s Region 2 said. “So the county health department actually made the decision there, literally overnight, that people had to move out of the building.”

Chief Mann’s relocation plan faces an additional hurdle due to the lack of federal recognition for the tribe. In 1980, the Ramapough Lenape Nation was officially recognized by New Jersey, but the federal government never followed suit, despite the tribe’s petitioning. After its decades-long struggle for recognition, the Bureau of Indian Affairs decided in 1993 not to acknowledge the tribe, right around the time that the Ringwood Superfund site was delisted

The U.S. Department of the Interior, which oversees the Bureau of Indian Affairs, maintains a set of seven specific criteria that tribes must satisfy to be federally recognized, including that a tribe have proof of its continued existence and political authority over members from “historical times until the present,” and that it is descended from, essentially, a federally recognized tribe. The 1993 ruling by the Bureau of Indian Affairs determined that the Ramapough did not meet those criteria.

The Ramapough have protested the decision, arguing the federal government was influenced by the casino industry and its allies, especially then-Rep. Robert Torricelli (D-NJ) and former President Trump, who vocally opposed the Ramapough gaining the right to open a casino of their own. In 1993, Trump, a casino owner at the time, was called to testify before Congress at a hearing on Indian gambling.

“They don’t look like Indians to me, and they don’t look like Indians to Indians, and a lot of people are laughing at it,” Trump told the committee, referring to the Ramapough and other tribes in Connecticut, who descend from common ancestors.

Chief Vincent Mann: ‘If we had our federal recognition, we’d have the strength.’

The tribe appealed the 1993 rejection and was denied again in 1996.

Under the Superfund law, federally recognized tribes have a right to directly engage, government-to-government, on how cleanups are done. The Ramapough don’t have that right, rendering their influence on the Ringwood cleanup process — and any potential relocation — to just input at public hearings and through community advisory groups. A listening session like the one convened last month is an “informal, government-to-government consultation,” according to Garcia.

Both Garcia and Mugdan stressed that Upper Ringwood is considered by the EPA to be an environmental justice community, determined to be overburdened by pollution and underrepresented in government, and added that the Biden administration is focused on prioritizing such vulnerable people.

“If we had our federal recognition, we’d have the strength,” Chief Mann said in the interview with NJ Spotlight News last year. “By us not, it’s taking away from the citizens who live in the area that we’re responsible for.”

Even if the EPA reevaluates the site and deems relocation of Upper Ringwood residents necessary, the agency will need to build a strong legal case to support changing the already-decided cleanup plans, and to compel Ford and the Borough of Ringwood to pay for the relocation.

Ford did not answer a question about paying for a potential relocation. Scott Heck, the Ringwood borough manager, said he is aware of Chief Mann’s idea, but added that his attention is on the cleanup plans underway.

“It’s not on my radar at all,” Heck said of the relocation proposal. “Right now I’m focusing on making the community better and making the community safe. And if in fact that relocation is a discussion down the road, I think that we’ll address it at that time. But right now, my focus is on the neighborhood and the remediation and making sure it’s done correctly, and making sure it’s done quickly and safely for those folks.”

It’s not just government regulators and lawyers that Chief Mann needs to win over; some of the residents he’s hoping to move will also need to be convinced.

This is a close-knit community with deep ties to the land they live on going back generations. It’s the kind of history that can make someone balk at leaving, regardless of present circumstances.

“Well, I’m not going to lie to you. I love it here,” said Valerie Gunn, the lifelong Upper Ringwood resident. “I absolutely love it here. It’s just things have to be done right. Things have to be done better. As far as relocating, I don’t know how that’s going to go over.”

Gunn also said she feels a sort of comfort in dealing with the danger she knows, rather than uprooting her life to potentially face new problems she may not anticipate.

Angel Stefancik: ‘There’s not enough money, there’s not enough jewelry, there’s not enough whatever to make me get out of this place.’

“To me it’s like, even though we have our problems, it’s like a safer place for us to live,” Gunn said. “That’s my only reason.”

Wayne Mann, a distant relative of Chief Mann, no longer lives in Upper Ringwood. But some of his closest relatives still do, and he says he knows they intend to live out their lives there.

“There probably is people who may want to go,” Mann said. “But there’s people who are so tied, because of history, because of their families. And that would probably rather just pass on there like others did in the last couple hundred years.”

Count 22-year-old Angel Stefancik in that group. The young mother has spent her entire life in Upper Ringwood and is clear she does not want to go. Stefancik said a relocation would be like the Turtle Clan accepting defeat.

“There’s not enough money, there’s not enough jewelry, there’s not enough whatever to make me get out of this place. You’re giving them what they want. They want us to uproot and just go. That’s their whole sole purpose. Because once they get their hands on our land, guess what? It’s free game,” Stefancik said, referring to outside entities.

Dennis DeFreese: ‘Because it’s never going to get better. I hate to say that. But you know in your heart.’

“I feel like this whole ordeal with us moving is wrong. If you want your indigenized land, stay here. You take it back,” Stefancik added. “You take your land back.”

But Dennis DeFreese, who lived much of his life in Upper Ringwood and now lives nearby, said he understands the appeal of leaving, and said he thinks others would be open to going too.

“Because it’s never going to get better,” DeFreese said. “I hate to say that. But you know in your heart.”

For his part, Chief Mann knows that not every Turtle Clan member in Upper Ringwood is ready to support relocating the community. This is the early stages of a very long process, he said, one that’s going to require a lot of discussion to sort out.

“There is a tremendous amount of thought process that has to be undertaken. There’s a tremendous amount of community involvement that has to take place,” Chief Mann said. “We really don’t have any clear answers to that, other than we’re pursuing this as one of the options to save our community, and to save our way of life.”

Whatever agreement the EPA, Ford, the borough and Chief Mann come to, if they come to one at all, it will not happen quickly. Meanwhile, Chief Mann and his wife have created the Munsee Three Sisters Farm, which sprawls across 40 acres in Sussex County and within the Turtle Clan’s historic range. The idea is to grow food for those still living in Upper Ringwood, who are fearful of raising fruits and vegetables from the soil beneath their feet.

“Even though we’re sitting here suffering and dying, we also are still doing the things that the federal government and state and the town’s local government can’t, or won’t, do,” Chief Mann said. “We took it upon ourselves to create this farm to help our people, because nobody else is.”

“Everything that’s taken place has played a part in stripping away the parts of our culture that we were able to retain by living where we live,” he said. “Now we’re at that time where, if we don’t stand up, we won’t be a part of those things that are for us, too.”

Editor’s Note: ‘Hazard NJ’ is an investigative podcast and multimedia project from NJ Spotlight News revealing the dangers climate change poses to the state’s Superfund sites and the health threats that poses to people. Subscribe to the podcast on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Amazon Music and more. Read stories and watch reports here.

Listen to the Hazard NJ podcast episode about this story: “Heart of Ringwood.”

Listen to the Hazard NJ podcast episode about this story: “Heart of Ringwood.”

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Jordan Gass-Pooré is creator and host of the Hazard NJ Podcast, in New York, New York.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. And now it’s time to check in on the state of science.

SPEAKER 1: This is KERA News.

SPEAKER 2: For WWNO–

SPEAKER 3: St. Louis Public Radio.

SPEAKER 4: Iowa Public Radio News.

IRA FLATOW: Local science stories of national significance. Superfund sites are the most polluted locations in the country. Actually, they’re abandoned industrial waste sites contaminated from hazardous materials. New Jersey has the most Superfund sites in the US. I’m talking a whopping 114.

A podcast from NJ Spotlight News, a division of New Jersey PBS, investigates what’s going on at those sites and how climate change is expected to impact the people who live nearby. Joining me now is my guest Jordan Gass-Pooré, creator and host of the Hazard NJ podcast, joining me from New York. Welcome to Science Friday.

JORDAN GASS-POORE: Thanks for having me, Ira. And yeah, joining from New York, not New Jersey, unfortunately. But I will be there tomorrow.

IRA FLATOW: OK. Let’s talk about what we’re focusing on today. Back to New Jersey, Ringwood, New Jersey, which I understand gets a whole episode of the Hazard NJ podcast. Tell me why. Tell me a bit about the history of Ringwood and the Indigenous people who live there.

JORDAN GASS-POORE: It does get a whole episode. It’s actually our longest episode so far. And that’s because of the decades-long struggle between an Indigenous group of people and Ford Motor Company. It’s this sort of David and Goliath struggle and has been one of the most fascinating episodes I’ve worked on so far with this show.

So one of the reasons Ringwood is so fascinating to me is it’s an abandoned mine, a former mining district. It was one of the first Superfund sites to be put on the National Priorities List. It is also the only Superfund site ever to be put back on the Superfund list.

IRA FLATOW: Wow.

JORDAN GASS-POORE: So it was put on it, taken off, said it was clean, and then put back on the list because, turns out, it was not clean.

IRA FLATOW: Wow, that’s some reputation to have.

JORDAN GASS-POORE: Exactly. Yes. And I mean, there’s a long history, like I said, with Ford Motor Company turning the mines– once the mines were abandoned, turning the mines into this toxic waste dump in the ’60s and ’70s. I mean, they polluted astronomically to this site. I mean, we’re still feeling the effects today, the people there in the borough of Ringwood. These toxins impact not only the land, but the groundwater in this community. And it continues to this day to threaten the health of the people that live nearby. And the people that live nearby are mainly members of a sect of the Ramapough Munsee Lenape Nation called the Turtle Clan.

IRA FLATOW: And then the Ford Motor Company came to town.

JORDAN GASS-POORE: Exactly. So when I mentioned Ford Motor Company, how they dumped a lot of toxins, we’re specifically talking here about thousands of tons of what is called paint sludge. And other ways, too. It came from the company’s assembly plant in a nearby town. So they dumped all this waste into the abandoned mines that are scattered throughout the Turtle Clan’s homeland.

IRA FLATOW: Wow, so it became a Superfund site when? Back in the ’80s?

JORDAN GASS-POORE: It did, yeah. So the Superfund program was established in 1980. And this site was officially put on the list in 1983. But in 1984 is when they started doing the cleanup work. And like I said, that cleanup work, as I’ll speak to later on in the episode, did not work out very well.

IRA FLATOW: You talked about how the paint sludge was left behind by Ford. Give us an idea of how toxic paint sludge is. What is it?

JORDAN GASS-POORE: Yeah. So toxic paint sludge came specifically from the Ford Motor Company’s plant, like I said, that was nearby. And when they were spraying the cars with the paint, there was residual, so the droplets that would collect on the ground and in the drains beneath the cars on the assembly line. So they would scoop up that residual sludge from the paint and take it off and dump it in the abandoned mines. So it’s a mixture of a lot of toxic chemicals, including lead and arsenic.

And one of the most, I think, fascinating things that I learned about paint sludge was it looks just like a normal rock when it hardens, that these toxins come together and it looks just like a normal rock. However, if you break it open, it smells like fingernail polish because of the acetone inside the rock. And sometimes, people have told us that sometimes when you crack it open, it’s still wet.

IRA FLATOW: Oh my goodness.

JORDAN GASS-POORE: Wayne Mann, he’s a Ramapough community leader who actually grew up in Upper Ringwood, and he also grew up playing with the paint sludge as a kid. He remembers playing with the paint sludge and not knowing exactly what it was.

WAYNE MANN: The one yard where they came, a kid was sitting, banging on something, playing with his trucks. But what he was banging on was a giant piece of sludge, lead. Another yard, kids were out swinging on a swing set. All around that yard and swing set was all protruding through the ground chunks of lead. It’s all Ford’s. But that was supposed to have been all cleaned up.

JORDAN GASS-POORE: So kids were playing amongst all this stuff, not realizing that it wasn’t just normal rocks. There are reports of people actually breaking open the rocks and using what was inside to paint their faces when they were playing games as kids.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. And then the EPA delists the site in 1994. But it’s really shoddy cleanup, right? You said it went in and then went out, went in, went out.

JORDAN GASS-POORE: Exactly. I mean, it only took Ford 11 years to clean up the site. And when you look at the history of the Superfund program, that is an extremely fast cleanup. Most sites take decades upon decades. Some sites aren’t even cleaned up to this day, obviously. So 11 years was nothing.

They cleaned it up very quickly, said, we’re done, and then the community members kept finding paint sludge. And people continued to get sick. And they put enough pressure on the EPA for them to come back and realize, yeah, maybe Ford didn’t clean it up very well, and we have to go back and spend more money and clean this site up. And cleanup still continues to this day.

IRA FLATOW: Amazing. So what have been the health effects in the community from all this paint sludge?

JORDAN GASS-POORE: Yeah, so many of the people that we spoke with, like I said, that– saying the contamination from the paint sludge has made them sick. I mean, there’s been cases of skin rashes. I mean, we’re not just talking about a skin rash that comes and goes, but severe skin rashes that stay for years and have long-term effects and scarring.

You have severe headaches, bleeding from the eyes, nose, and throat. But really, the kicker is various cancers. So I mentioned in the episode that so many people have cancer in this community that locals call a particular street, which is named Van Dunk Lane officially– they call it Cancer Row because nearly every household on Van Dunk Lane has been touched in some way by cancer.

IRA FLATOW: No kidding.

JORDAN GASS-POORE: However, I will mention here, too, that so far there has been no direct link between the diseases I mentioned and the paint sludge. So there’s been nothing scientifically proven that the paint sludge has caused any of these diseases.

IRA FLATOW: All right. So you have this cleanup site, and now we have climate change coming through, right?

JORDAN GASS-POORE: Yes.

IRA FLATOW: What could go wrong here?

JORDAN GASS-POORE: What could go wrong? A lot of things could go wrong. The most minor effect of it are sinkholes. And there have been reports of sinkholes literally appearing in people’s backyards. They go outside doing some work, go back inside to get a tool, come back out, and there is a sinkhole because the land sits above abandoned mine shafts.

And we don’t know exactly how many abandoned mine shafts are in this area. We don’t have maps that point us to these exact locations. So you got sinkholes. But that, like I said, is like the least of our concerns when we’re talking about climate change.

We have more prevalent and intense forest fires, which means that some of these dangerous toxins could be released in the air. We also have drought. That’s going to make these health problems worse.

You have rainstorms that are going to be more intense and more frequent. So when that heavy rainfall comes down, you have the water rushing through the old mines in the fault lines and cracks in the rock. If that happens, the water could flush contaminated groundwater into nearby streams and rivers. I mean, those bodies of water are already polluted. So you have a lot of climate impacts potentially happening in this area that’s already been hit hard with disease.

IRA FLATOW: And there was a class-action suit brought against the Ford Motor Company, right?

JORDAN GASS-POORE: There was, yes. HBO even made a documentary about the class-action lawsuit. Wayne Mann was the name of the plaintiff in the case, which is called Mann v. Ford– also the name of the HBO documentary. And in this case, let’s say roughly 600 of the residents in Upper Ringwood sued Ford Motor Company and other defendants, including the borough of Ringwood.

And what they were looking for were collecting damages for the impact of all of that paint sludge dumping, so property damage and personal injury. And they did, I would say– they had some success with this lawsuit. The Ringwood residents that sued, they got about $11 million in total. However, when you start breaking that $11 million down for the families involved, we’re looking at maybe each family member receiving about $8,000 each.

IRA FLATOW: Wow.

JORDAN GASS-POORE: So it’s not a lot of money.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. Yeah. Is the Ramapough tribe still asking for something else? Are they happy, or what would they like to happen?

JORDAN GASS-POORE: Yeah, so some folks would like to be completely removed, permanently removed from this land and moved to another location to start new. Other folks just want this site to be cleaned up once and for all and be able to stay on the land that they know and where they were raised. So there’s sort of a split in opinion for some folks that live on the land.

IRA FLATOW: So I imagine you’ll be following this story as it continues.

JORDAN GASS-POORE: Yes, and I imagine it will continue for a number of years. 2024 is the expected date for the second cleanup to be complete. So we’ll see.

IRA FLATOW: OK, and we’ll have you back to talk about it then, OK, Jordan?

JORDAN GASS-POORE: That would be great.

IRA FLATOW: Jordan Gass-Pooré, creator and host of the Hazard NJ podcast, joining me from New York City. And more episodes of the Hazard NJ podcast will come out this fall.

Copyright © 2022 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/.

Kathleen Davis is a producer and fill-in host at Science Friday, which means she spends her weeks researching, writing, editing, and sometimes talking into a microphone. She’s always eager to talk about freshwater lakes and Coney Island diners.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.