When Trapping Invasive Bugs Is Science Homework

4:54 minutes

The spotted lanternfly, an invasive species, was first introduced to the U.S. in Pennsylvania, around 2014. Since then, it has spread aggressively, and has now been spotted in 11 states. The bug is pretty—adult spotted lanternflies are about an inch long, and feature striking spotted forewings and a flashy red patch on the hindwings. But they are also very hungry, and pose a significant threat to agricultural crops, including grapevines.

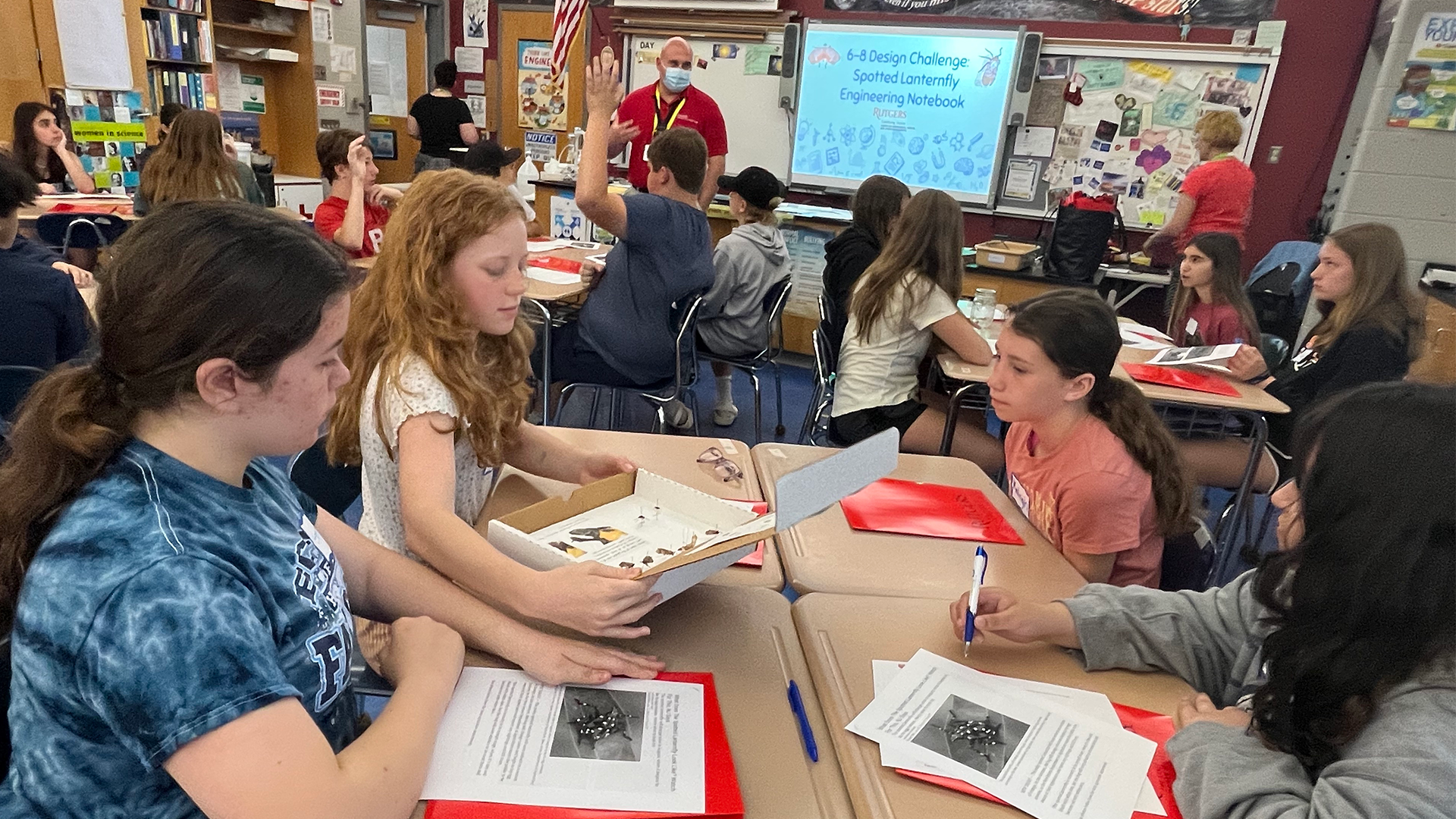

Many control efforts have focused on either stomping the insects on sight, or on spotting and destroying the egg masses that the lanternflies lay in the fall. However, researchers have been developing trapping techniques for the bugs as well. One, involving a sticky band looped around a tree, is effective—but can also snare other insects and even birds. Experts at the Penn State Extension have come up with a new style of circle trap for lanternflies, based upon an existing trap for pecan weevils. Now, STEM educators at Rutgers University are using that design as the starting point for an engineering design challenge, asking K-12 teachers and students to come up with improvements to the design.

The students are given basic information about the spotted lanternfly, its life stages, preferred foods and habitat, and its behavior. They’re then introduced to design principles and materials that they can use to prototype, build, and test traps. Dr. Brielle Kociolek, the iSTEM coordinator at the Rutgers University Center for Mathematics, Science, and Computer Education in Piscataway, New Jersey, joins Ira to talk about the program, and share some of the students’ innovations.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Briellle Kociolek is the iSTEM Coordinator in the Center for Mathematics, Science, and Computer Education at Rutgers University in Piscataway, New Jersey.

IRA FLATOW: More on invention now. We have talked about the efforts to halt the spread of the invasive spotted lanternfly, remember? It was accidentally introduced in Pennsylvania in 2014. It has now been found in 11 states.

It’s a pretty insect. The adults are about an inch long with a striking spotted pattern on the forewing and a bright patch of red on the hindwing. But it’s also very hungry and a threat to many important agricultural crops. We have been encouraged to stop on them to help slow the spread– really old tech.

You know what we really need? We need a good old bug trap. And that’s what science educators at Rutgers University in New Jersey have been doing, a project asking teachers and students to design, to invent traps for the spotted lanternfly. Joining me now to talk about that is Dr. Brielle Kociolek. She’s the iSTEM coordinator in the Rutgers University Center for Mathematics, Science, and Computer Education. Welcome to Science Friday.

BRIELLE KOCIOLEK: Thank you so much for having me. I’m looking forward to helping bring about innovation and invention to deal with this problem.

IRA FLATOW: Well, you’re very welcome. Now, to build a trap, what’s the guiding bits of information here? What do you need to know about the lanternfly biology or its behavior?

BRIELLE KOCIOLEK: Definitely looking at the life cycle. That’s kind of where we start with teachers and with students– and we’ve worked with K through 12 teachers and then K through 12 students– is talking about that life cycle and how, right now, we’re in August, and that’s when you’re going to find more of the fourth instar and the adult lanternflies. So if you’re building traps right now, you want to think about, OK, I have the adult bug that I’m trying to catch. They don’t fly. They more like hop, so thinking about how they get on and off of the trees, on and off the vineyards. Or if we’re building the traps more in April, May, June, which we’ve done as well, we’re looking at the really tiny first-stage instar. So that’s a big factor.

And then also thinking about what you’re going to put the trap on. So is it going to be on an apple tree? Is it going to be on a grape vine? Because those sizes are going to affect the type of trap as well.

IRA FLATOW: Right. It looks like the idea here is more encompassing than just building a trap. It seems to be all about the process of the design, right? Getting kids to think about how to design it.

BRIELLE KOCIOLEK: Absolutely. We use the engineering design process, so we’ve connected with the science standards, the engineering standards, NGSS. So we go through those steps of the ask and the research and planning and coming up with different prototypes and brainstorming. We also use– which is really neat– it’s a type of a morph chart, where it really gets them to think about the materials they’re using to build and then also what stage of the lifecycle and then, again, what type of tree you’re using, too.

IRA FLATOW: All right. Let’s talk then– drum roll, please– about the basic trap that you’ve come up with. How does it work?

BRIELLE KOCIOLEK: So we started with looking at Penn State University. Their extension created one, and we gave our students and our teachers a whole bunch of other materials for them to use. So we have netting. We have wire. We have recycled materials. We have string and yarn.

They actually get a chance to draw out and play with all the materials before they build. And we’ve had great conversations, like one teacher actually noticed that the lanternflies love to be on the metal ramps in Newark, where she teaches. So other teachers asked, hey, can we use foil on our traps to see if that heat or that absorption of heat on that metal will attract them more? And then a lot of the students also come up with ways for it to blend into the environment. So they’re taking some of the stuff from nature like bark and other materials to try to put on the track to have it blend in so it doesn’t stand out.

IRA FLATOW: So the trap is basically some mesh netting that wraps around a tree and then funnels the insects into a collection bag of some kind.

BRIELLE KOCIOLEK: Exactly. And then it will vary in sizes, again, depending on the tree. I will say, students struggle a little bit with understanding the size of the trees. So it’s helpful if you can get them outside to really observe the environment before they start building so that they can better understand the sizes that they need for the traps.

IRA FLATOW: That is very cool. They are very creative, and you should be commended for taking on the project, Brielle.

BRIELLE KOCIOLEK: Thank you. I’ve enjoyed it. We definitely love problem-based and engineering and design challenges.

IRA FLATOW: Brielle Kociolek is the iSTEM coordinator in the Rutgers University Center for Mathematics, Science, and Computer Education. Thank you for taking time to be with us today.

BRIELLE KOCIOLEK: Thank you so much.

IRA FLATOW: You’re welcome. And if folks want to build their own, we have pictures and information on building lanternfly traps all there up on our website, sciencefriday.com/bugtrap.

Copyright © 2022 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

As Science Friday’s director and senior producer, Charles Bergquist channels the chaos of a live production studio into something sounding like a radio program. Favorite topics include planetary sciences, chemistry, materials, and shiny things with blinking lights.

Sandy Roberts is Science Friday’s Education Program Manager, where she creates learning resources and experiences to advance STEM equity in all learning environments. Lately, she’s been playing with origami circuits and trying to perfect a gluten-free sourdough recipe.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.