This Soundscape Artist Has Been Listening To The Planet For Decades

17:03 minutes

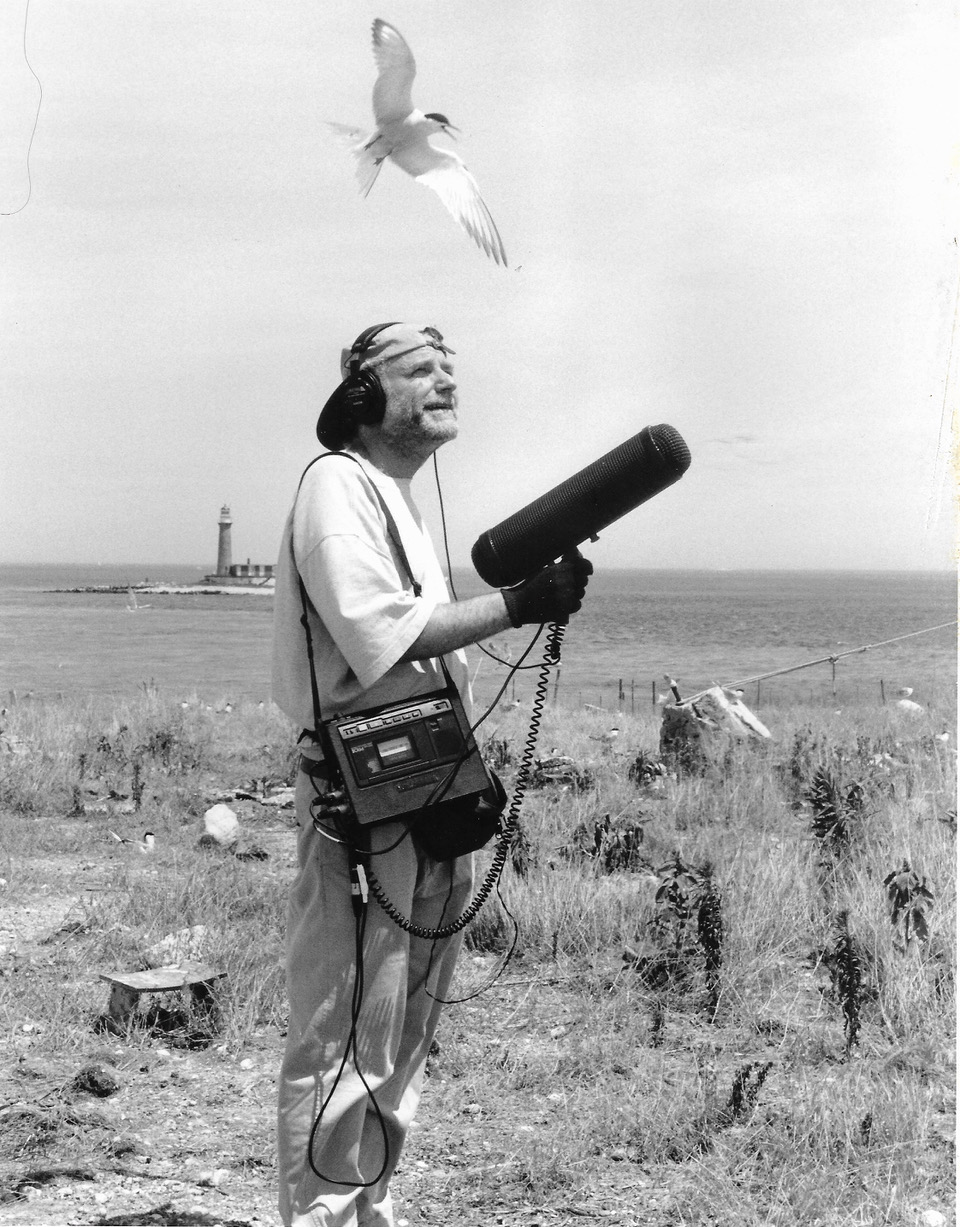

Jim Metzner is one of the pioneers of science radio—he’s been making field recordings and sharing them with audiences for more than 40 years. He hosted shows such as “Sounds of Science” in the 1980s, which later grew into “Pulse of the Planet,” a radio show about “the sound of life on Earth.”

Over the decades, Metzner has created an incredible time capsule of soundscapes, and now, his entire collection is going to the Library of Congress.

John Dankosky talks with Metzner about what he’s learned about the natural world from endless hours of recordings and what we can all learn from listening. Plus, they’ll discuss some of his favorite recordings. To hear the best audio quality, it might be a good idea to use headphones if you can.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Jim Metzner is an audio recordist and radio producer based in Kingston, New York.

JOHN DANKOSKY: This is Science Friday. I’m John Dankosky. I don’t know about you, but for years, the alarm clock in my bedroom woke me up with my local public radio station. And what voice did I hear very first thing in the morning?

JIM METZNER: Every summer, the McNeil River in Alaska is filled with spawning salmon. It’s an annual feast that bears in this region have come to rely on. I’m Jim Metzner, and this is the pulse of the planet.

JOHN DANKOSKY: And it wasn’t just Jim’s voice that eased me out of my sleep. It was the weird and wonderful sounds that he gathered from around our planet. Maybe your memory goes back even further to his show The Sounds of Science, where his guests included Koko the gorilla.

SPEAKER 1: She’s nice to be with. She’s got a sense of humor. She’s very warm and outgoing.

JIM METZNER: And she is a gorilla.

[GORILLA VOCALIZING]

I’m Jim Metzner, and these are the sounds of science.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Jim Metzner is one of the pioneers of science radio, making field recordings and sharing them with audiences for more than 40 years. And now, this time capsule of sound he’s created– his entire collection– is going to the Library of Congress. Today, we’re going to talk with Jim about what he’s learned about the natural world from endless hours of recordings and what we can all learn from listening. We’re going to hear some of his favorite recordings, too. So I don’t know– if you can listen along with headphones, now might be a good time to put them on. Jim Metzner, welcome back to Science Friday.

JIM METZNER: Hi, it’s a pleasure to be here. And I just wanted to tell you, to put a bookend on it, you might have wakened with my voice, but my voice puts my wife to sleep every night.

JOHN DANKOSKY: [LAUGHS]

Well, I certainly appreciated waking up to your voice all those mornings on Pulse of the Planet. Of all the ways that you can tell a story, Jim, why do you think sound helps us understand the world around us so well?

JIM METZNER: Ooh, boy. We could talk about that the whole day. It’s such a great question. How is it that sounds grab you? Where do they hit you?

They certainly hit me where I live. There’s a voice, but then there’s the sound of my mother’s voice. There’s the sound of something that I grew up with. It’s like a sound that came in and never left. Sounds are the touchstones to our emotional world, our emotional life. So that’s part of it.

They also seem to trickle down, as if there was some cave inside. The sounds trickle down and go to places where words don’t go. And they tell us things. You could be listening to somebody, and you can tell as much by the sound of their voice as what they are saying.

JOHN DANKOSKY: I want to actually play a sound here that I know really resonated with you. It’s the sound of a parrot and a girl laughing, Jim.

SPEAKER 2: [PORTUGUESE]

[LAUGHTER]

[PORTUGUESE]

[LAUGHTER]

PARROT: [PORTUGUESE]

SPEAKER 2: [PORTUGUESE]

[LAUGHTER]

[PORTUGUESE]

[PARROT SCREECHES]

[PORTUGUESE]

PARROT: [PORTUGUESE]

[LAUGHTER]

JOHN DANKOSKY: So of course, I can’t help but to laugh when I hear that. Tell us about that sound.

JIM METZNER: I still smile and laugh every time I hear it. This recording– so it took place in Brazil, in Bahia. I was in Bahia in the ’70s. I was in my 20s. And I stumbled upon this group of young women who were all clustered around another woman with a parrot.

And they’re talking back and forth, and it was a serendipitous moment. I waltzed in and recorded it. And what the parrot is saying– in Portuguese, of course– “I’m mad at you.” And the girl says, “You’re mad at me?” “Yeah, I’m mad at you.”

But it’s like– the glee of this moment. You know, I think I could play this anywhere in the world, and people would get it. There’s something in that sound that just cracks everybody up.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Yeah, and that’s– as you say, it sort of touches a place inside you that just hearing people talk isn’t going to do. The sound of people’s laughter is something that we have a physiological response to, Jim.

JIM METZNER: Yeah. Yeah. And I bet you, there’s something about the sound itself, sans video, that just does it. I don’t think a video would necessarily help. It’s the sounds that carry that emotion.

JOHN DANKOSKY: So let’s go back a little bit to the start of your series Pulse of the Planet. It’s this very popular series in which you’ve intertwined science and nature and culture in these really short, beautiful segments. They were on hundreds of public radio stations around the country. Do you have an idea of what the pulse of the planet is?

JIM METZNER: Is the pulse of the planet what we hear on the daily news every day? I hope not. Underneath sort of the tsunamis of the news, there’s something else going on. There’s the seasonal rhythms of nature. The whales are migrating, the cicadas are emerging, and so forth.

JOHN DANKOSKY: When you said that, the thing that resonated with me is I remember being in the rainforests in Costa Rica and feeling– I don’t know what to say. It’s a vibration coming from around you. And as you listen, you hear millions of insects and birds and other animals and people and motorbikes and the ocean waves, and they’re all coming together. And it feels like this vibration of the Earth. And if you think about– I mean, at least for me, the pulse is not a regular glub-dub, glub-dub that a human would have. But it’s this raw, amazing, vibration that’s coming from everywhere.

JIM METZNER: Yes, indeed. It’s many. It is diverse. It is varied. It’s ever changing. So if you were in the rainforest, you’d notice that there was a different sound at night than in the morning, of course. And you don’t have to go to the rainforest to hear that. Anyone in the country or, I dare say, the city as well– sounds morph and change moment to moment.

JOHN DANKOSKY: So take us through a day of field recording. Like, what is it like? When you go out with a microphone, what are you carrying? Does anybody come with you? Just give us a little day in the life, because I think our listeners would really love to know how you go and capture the sounds, especially of the natural world.

JIM METZNER: OK. I rarely use the word “capture.” I’ll tell you why in a moment. But it’s a great question. I’d remind listeners that right now, for the first time in human history, virtually every one of us is carrying a sound recording device in our pocket. And it makes a damn good recording.

And so go out today. Take a sound walk, and you record the sounds. Please, listeners, try it, whether you’re interviewing mom or grandpa or whoever or just the sounds of the neighborhood. Go on a journey of discovery.

But if I go out with a recorder, there’s no typical day. No typical day. And that’s the beauty of sound recording. And I tend to be a bit more inclusive. I don’t go out and say, I’m going to record a yellow-bellied sapsucker today or whatever. I mean, if it comes across my path, then great. But I usually, rarely– sometimes, however, I do go out and search for sounds. But more often than not, whatever comes my way is grist for the mill.

JOHN DANKOSKY: I want to play another sound that you sent along to us as one of your favorites. And this is a sound that is very rich and varied. It was recorded in Grampians National Park in Victoria, Australia. Let’s listen for a moment.

[BIRDS CHIRPING]

[WHIRRING]

[BIRDS CHIRPING]

Jim, what are we hearing there?

JIM METZNER: So there I was in Grampians National Park just west of Melbourne, a park that is run by Indigenous peoples. It was an extraordinary place. And one of the a great visuals– it had nothing really to do with the sound, but I’ll just tell you because it was just so out of the ordinary. I was surrounded by kangaroos. [LAUGHS]

They weren’t making any sounds, but there they were. And then, of course, there were this canopy of trees and this immense, textured panoply– I’m running out of adjectives to try to describe it because words only dance around what sounds do. They do so much better than words.

But I think the challenge for me, and maybe other listeners, too, is I see that, typically, honestly, I don’t know how to listen to the sounds of nature. I mean, it’s wondrous at moments. But if you’re going to sit down and listen to a Bach concerto or a little bit of Mozart, you could give yourself 10 minutes for that, easy. Longer maybe. But for sounds which are every bit as interesting and varied, we don’t typically have that kind of training and experience.

So I’m still learning how to listen to– and you can listen for species. Oh, that’s a lyrebird, for example. Or you could listen in another way to this orchestration.

JOHN DANKOSKY: That’s so interesting the way that you just put that, Jim, though, because by contrast, if you’re listening to a Bach keyboard piece, part of the context that’s important to you is you know that this man, some hundreds of years ago, wrote this piece, and it’s been adapted and adopted. And all the context of it is also what you’re listening to and for. But that sound that we just heard, we might not know what any of the birds are that we just heard. But the sound itself clearly is beautiful. It speaks to a natural environment that we can potentially imagine in our minds. And it’s just so evocative of something and hits us in a way that, even without context, I think people might think is just stunningly beautiful.

JIM METZNER: I think so, too. And just following your line of thought, you could say, unlike a Bach who only put a year, a mere 10 years into it, this is the result of a million years of evolution that we’re hearing right now. They’ve been working on it for a long time.

JOHN DANKOSKY: They’re finally starting to get good at it, huh?

[LAUGHTER]

I have to ask you, with all of these sounds that you’ve collected over all of these years– they’re now going to go into the Library of Congress. I mean, it’s the most basic question in the world, but how does that make you feel? That must be an amazing feeling to know that you’ve contributed so much and that people will be able to experience these sounds forever.

JIM METZNER: Yes. Recording is often a solo endeavor. You go into a booth. It’s a solo endeavor. You know that a lot of people are listening, but that’s sort of like an idea.

To know that these vibrations will be heard– that’s why I don’t use the word “capture.” These were incredible gifts to me. I was extraordinarily honored to receive these sounds, to be the one who was entrusted with them.

And so the imperative to share them. So how do you share them? That’s in part up to the library. To me, I’m writing a book about my adventures called Adventures of a Lifelong Listener.

So to answer your question, it’s like– I mean, every time you press the red button, it’s with the hope that something wonderful will happen. Sometimes it does. Sometimes it doesn’t. And then there’s that imperative, that human imperative, the wish to share these vibrations with other sentient beings because in the act of sharing, it’s like we’re all resonating again together with the environment, with the world around us.

So in the act of sharing and knowing that, for centuries, people will share in these vibrations, it’s a good feeling. But also, I feel like I’ve fulfilled my part of the bargain, that I was given this material and now I’ve done my best to share it in a way that hopefully will reach across the gap.

JOHN DANKOSKY: I’m John Dankosky, and this is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. I’m talking with Jim Metzner, the host of Pulse of the Planet, about all the many recordings that he’s made of our world. They’re all going to the Library of Congress.

I’d like to share one more sound that you brought us here. And I won’t even set this up first. Let’s just listen to this sound that you’ve sent along.

[HIGH-PITCHED VOCALIZATIONS]

SPEAKER 3: Right now, we’re covering them with blankets and sheets, one, to keep the sun off them and keep them moist, and also to, in some degree, help them control their body temperature. They can quickly overheat in a situation like this. So we’ll keep the water on to keep them cool. Or in some cases, if they go into shock, they could start getting cold. In that case, we’ll use other things and put more blankets on and try to keep them warm.

JOHN DANKOSKY: This is a good example, Jim, of something where if you give people just a little bit of information or no information at all, they can make up their own minds. Tell us where you recorded this sound.

JIM METZNER: I was in Cape Cod some years back, just driving around listening to the radio. And it was a call out to this ad hoc network of seat-of-your-pants animal rescuers, just vigilante rescuers, anybody within the sound of the voice of the announcer, to come because there was a whale– pilot whales were beaching at this particular location. I thought, well, I’m near there. I’m going to show up.

And I had my tape recorder with me. So they show up, and I’m with them. And they’re trying to rescue these whales who have beached themselves for no apparent reason, one of these odd quandaries that we’re still facing– why do whales beach? We really don’t know.

And so I joined them and saw that they were putting blankets on them to keep– just as this man was describing. And then they were trying to lift, getting blankets underneath them and stretchers that they were jury rigging, and taking them out and trying to get them out swimming again. And at a certain point, I just put down my microphone and joined in.

But for a moment, to hear the sounds, to be with them, and to look a whale in the eye from close up, which I’d never had that experience before, was extraordinary. And to think that you were helping– how could you not want to help them and feel for them and see that all of these people with the best of intentions were trying to do the best they could to help these fellow creatures?

JOHN DANKOSKY: Before I let you go, Jim, quickly, I’d love to hear about your American Soundscapes Project. It’s a crowdsourced project where people can submit their own special sounds. Can you tell us about it?

JIM METZNER: Thank you. Americansoundscapes.com. You can be among the first to check it out in its beta form. So if you go, you’ll see that there are some featured soundscapes from some professional sound recordists, some of the best sound recordists I know of. But the chance for anybody, using that sound recording device that you have in your pocketbook or back pocket, to go out, take that journey of discovery that we were speaking about earlier– go out and have your own journey that way and send it in.

It doesn’t have to be a whale rescue. It can be something as simple as the bells of the church in the town where you live, the sound that your grandfather makes whenever he picks up a heavy box, a word that only your family knows and is privy to, or whatever sounds that are in your home, your neighborhood, your environment, or in your cultural group that are significant, that are emblematic, that are significant. They can be sounds of nature or culture, but share them with us. This American Soundscape Project is an opportunity for us to share our sounds with each other.

JOHN DANKOSKY: That’s fantastic. Jim Metzner, thank you so much, and congratulations.

JIM METZNER: Thank you. Been a pleasure.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Jim Metzner is a field recordist and radio producer based in Kingston, New York. His entire collection of sounds is going to the Library of Congress. But you can’t listen to all of them there just yet, though. That much sound, it takes a while to upload.

Copyright © 2022 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tigt deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/.

Rasha Aridi is a producer for Science Friday and the inaugural Outrider/Burroughs Wellcome Fund Fellow. She loves stories about weird critters, science adventures, and the intersection of science and history.

Jason P. Dinh is Climate Editor at Atmos Magazine in Washington, DC. He previously was an NSF-funded intern at Science Friday.

John Dankosky works with the radio team to create our weekly show, and is helping to build our State of Science Reporting Network. He’s also been a long-time guest host on Science Friday. He and his wife have three cats, thousands of bees, and a yoga studio in the sleepy Northwest hills of Connecticut.