The James Webb Telescope Releases Its First Focused Image

12:12 minutes

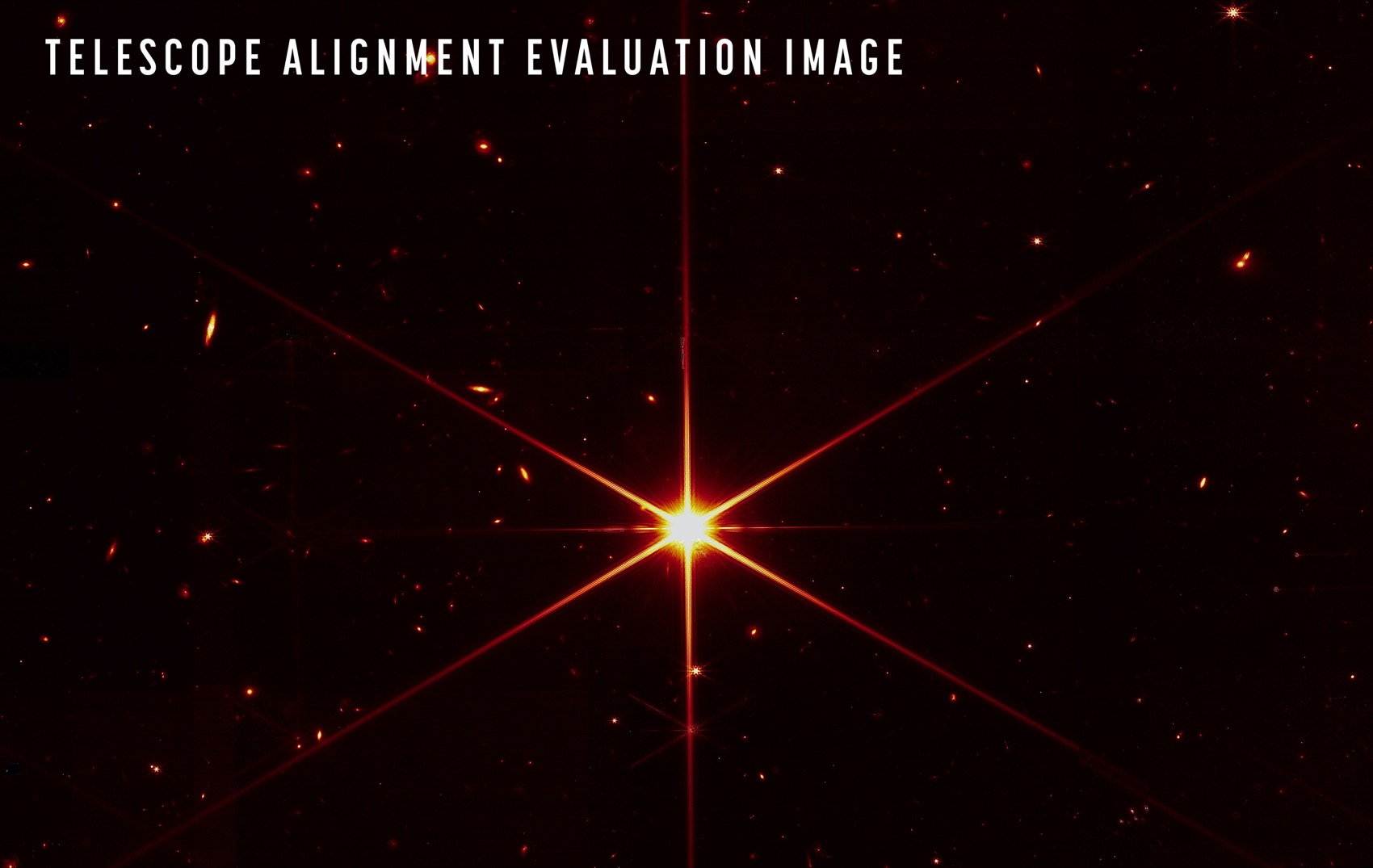

This week eager astronomers got an update on the progress of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), which launched last December. After a long period of tweaking and alignment, all 18 mirrors of the massive orbiting scope are now in focus.

In a briefing this week, Marshall Perrin, the Webb deputy telescope scientist, said that the team had achieved diffraction limited alignment of the telescope. “The images are focused as finely as the laws of physics allow,” he said. “This is as sharp an image as you can get from a telescope of this size.” Although actual scientific images from the scope are still months away, the initial test images had astronomers buzzing.

Rachel Feltman, executive editor at Popular Science, joins Ira to talk about the progress on JWST, and other stories from the week in science, including plans to launch a quantum entanglement experiment to the International Space Station, an update on the COVID-19 epidemic, and a new report looking at the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. They’ll also tackle the habits of spiders that hunt in packs, and the finding that a galloping gait may have started beneath the ocean’s waves.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Rachel Feltman is a freelance science communicator who hosts “The Weirdest Thing I Learned This Week” for Popular Science, where she served as Executive Editor until 2022. She’s also the host of Scientific American’s show “Science Quickly.” Her debut book Been There, Done That: A Rousing History of Sex is on sale now.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. Later in the hour, a look at upping your home energy efficiency, and some true wildlife crime. But first, this week, eager astronomers got an update on the progress of the James Webb Space Telescope. And boy, were they happy. After a long period of tweaking and alignment, all 18 mirrors of the massive orbiting scope are now brilliantly in focus. In a briefing this week, Marshall Perrin, the Webb Deputy Telescope Scientist, described the level of precision.

[AUDIO PLAYBACK]

– This is a process that we’ve prepared and practiced for years, and now we’ve had a chance to run that plan. And it’s just an absolute thrill to be able to say that everything worked. And we now have achieved what’s called diffraction-limited alignment of the telescope. The images are focused together as finely as the laws of physics allow. This is as sharp an image as you can get from a telescope of this size.

[END PLAYBACK]

IRA FLATOW: Here to talk about that and other stories from the week in science is Rachel Feltman, Executive Editor at Popular Science. Welcome back, Rachel.

RACHEL FELTMAN: Thanks so much for having me, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: You’re welcome. OK. So the Webb Telescope mirrors are all aligned and working well so far. A big step, right?

RACHEL FELTMAN: Yeah, this is huge. To have all of these mirrors aligned is quite a feat. It’s a multi-step process that they started back in January. Combined, they make a collection area that’s about six times as big as Hubble’s main mirror. But of course, making a space mirror that large that wasn’t too heavy and unwieldy to get into space was the reason that they engineered these super high-tech multifaceted mirrors. But then the challenge is to make them one perfectly smooth surface. And that required precision down to the nanoscale. So this is very cool.

IRA FLATOW: OK. So walk us through. How do you line up all those segments? What do you use in space there?

RACHEL FELTMAN: Previously, in some previous steps of this, those 18 mirrors were all individually pointed on this one star in the Milky Way, called HD 84406, a very poetic name. And previously, we were basically getting 18 mediocre images of this one star. And once the alignment was perfect, they combined to create one really, really, really awesome image of that star.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, it is a very pretty picture. And you can see it up on our website. And you can see other stuff in that photo as well.

RACHEL FELTMAN: Yeah, exactly. So obviously, the image of the star itself is beautiful– beautiful resolution. But what’s really cool is that you can see other galaxies behind it. And that is exactly– well, one of the many things that we’re excited about the JWST being able to do. It’s going to have that depth of field that’s going to allow it to look at some of the oldest galaxies in the universe.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. And so when is all this tinkering done? And when does it really go to work?

RACHEL FELTMAN: Yeah, exactly. So obviously, it’s very exciting to see any images at all from this telescope that we’ve been anticipating for so long. But these are, of course, still just part of the testing and calibration phase. And it’s going to be sometime during the summer that we actually see it starting its scientific mission. And hopefully, shortly after, we’ll start to see some beautiful images.

IRA FLATOW: Cool. OK. Let’s go on to other space news, some of my favorite kinds of stuff. And I’m talking about some spooky quantum world stuff. NASA’s going to launch a quantum entanglement experiment into space. Wow. Tell us about that.

RACHEL FELTMAN: Yeah. So it’s funny, because this is just like a little thing the size of a milk carton that’s going to launch to the ISS later this year and get kind of stuck outside one of the airlocks. It doesn’t look too exciting, but yes, it is a quantum experiment. And the idea is for this to be getting us one small step closer to being able to use quantum computing in such a way that we can have quantum sensors in space and quantum computers on Earth talking to each other instantaneously.

IRA FLATOW: It used to be called– or Einstein called it– spooky action at a distance, right, this entanglement?

RACHEL FELTMAN: Right. Yeah. So photons have this really interesting and spooky quality of, if they become entangled, they act as if they’re connected, no matter how far they’re physically drawn apart or what barriers lie between them. So in theory, if you create and maintain entangled particles like this, you could create a quantum network of computers or sensors, these nodes of entangled photons, that can share information over great distances, even across the vastness of space– theoretically, of course.

IRA FLATOW: Theoretically, of course. OK. Let’s go back to Earth for a minute, shall we, and some more sobering news. Because COVID isn’t going away any time soon, is it?

RACHEL FELTMAN: No, unfortunately not. The good news first is that US COVID metrics are very much improved from that high point of the Omicron spike a couple of months ago. Deaths are going down. Hospitalizations are going down. Cases are going down. But unfortunately, we may be jumping the gun a little bit on our lowering of funding and protection and protective action.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. Because we need to keep up research into this. Because it’s probably going to keep mutating.

RACHEL FELTMAN: Right, exactly. So a lot of European countries are seeing surges. And generally, throughout the pandemic, that’s been an indication that the US can expect another surge. And yes, COVID is still mutating. Recently, researchers confirmed that it does seem very likely that there is a so-called Deltacron mutation, meaning that they’re seeing strains of the virus that have some of the mutations we saw in Delta and some from Omicron.

Now, that doesn’t mean it will have the worst of both of those strains. It doesn’t mean that at all. And mutation is normal. But the reason for concern is that there’s a lack of funding. There’s a general sense that the US is just kind of done with the pandemic. And then we also have waning immunity. The most vulnerable folks got boosted mostly in the fall, which means their protection has dropped significantly since then. And we see mask and vaccine mandates dropping in places like New York City.

I was on the subway the other day, and suddenly, like, no one was wearing a mask. Which I don’t get.

IRA FLATOW: No.

RACHEL FELTMAN: Because it’s stinky on the subway. It’s a great place to wear a mask. And then, of course, kids under five are still not able to be vaccinated.

So while we are doing much better than we were a couple of months ago, we really have to stay vigilant, so that we can not slide back.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. We’re waiting for more funding to come through Congress.

You have a story for us about diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease.

RACHEL FELTMAN: Yeah. So this new report from the Alzheimer’s Association suggests that more than half of Americans may be mistaking what could be early signs of dementia for normal aging. They surveyed about 2,400 people on symptoms of what’s called mild cognitive impairment, or MCI. And that doesn’t necessarily progress to severe dementia. It only does in 10% to 15% of people. But it is a warning sign. And it’s generally a sign that something is wrong. It’s not actually a harmless side effect of aging, the way many Americans seem to think that it is.

IRA FLATOW: Hmm. So what’s the take-home message here? What should people do?

RACHEL FELTMAN: Yeah. So I mean, MCI is things like forgetting important info, losing the ability to make sound decisions, not being able to sense the passage of time, impaired visual perception. It’s the kind of stuff that people would be like, oh, I’m having a senior moment. And the thing is that lack of sleep, poor nutrition, and vitamin deficiencies can all cause MCI and are all treatable. So nobody should panic and think that having a little lapse of memory means they are certainly going to develop severe dementia. But you should be proactive and talk to your doctor about it.

Because the truth is, you probably can do something to regain that little lapse of cognitive power. Which is great. And if not, then you can catch that increasing dementia early, which means you can work with the doctor to find both behavioral and lifestyle, and perhaps even pharmaceutical, interventions that help you maintain your good quality of life and health for longer.

IRA FLATOW: Great. I’m glad we we’re talking about that.

Let’s move on to something a little bit lighter. You have a story– I’m not sure that people want to hear about it, because it involves spiders.

RACHEL FELTMAN: It does.

IRA FLATOW: Spiders. Not only spiders, but they’re hunting in packs. Tell us about that, please.

RACHEL FELTMAN: They are. Yeah. I personally was not aware before the study that there are social spiders. And I have to say that’s one animal I don’t really want to think about being social. But about 20 of the roughly 50,000 known spider species do live in colonies. And Anelosimus eximius actually can live in packs as big as 1,000, which I don’t love that.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. Whoa.

RACHEL FELTMAN: Yeah. And this South American spider, in those packs, they build connected webs. So they can span several feet collectively. And it was already suspected that they used the vibrations on those webs to coordinate hunting, because they do this kind of coordinated swarm that allows them to take down prey 15 times larger than each individual spider. Which, again, I don’t really love.

IRA FLATOW: Wow.

RACHEL FELTMAN: But scientists we’re really curious about how they do this. And it turns out they monitor not just the way the prey is moving, but also they monitor the vibrations in the web of each other’s movements. And they use that information to start and stop, so that they can all time their arrival at the prey, to be in sync. Because otherwise, a little spider is going to get eaten by this big bug they’re trying to kill.

IRA FLATOW: Right.

RACHEL FELTMAN: So frightening, but fascinating.

IRA FLATOW: And they’re in South America.

[LAUGHTER]

RACHEL FELTMAN: Yeah.

IRA FLATOW: OK. Finally, as we gallop toward the weekend, you have a story about how the gallop came to be.

RACHEL FELTMAN: Yeah. So most humans are familiar with the gallop by way of horses, but it’s a really fascinating movement. You know, when animals walk or trot, that’s a very evenly timed pattern, known as a symmetrical gait. And to travel more quickly, a lot of animals switch to asymmetrical gaits, like a gallop, where all four feet are hitting the ground at unevenly spaced intervals. There are even aquatic animals that use their fins to kind of do this, which is called crutching or punting.

So it was already pretty widely accepted that galloping must have evolved multiple times throughout the animal kingdom. But in this new study, researchers observed movements of hundreds of species. And they concluded that these asymmetrical gaits emerged probably first in ancient fish-like animals, before vertebrates, before anything crawled up onto land, or galloped up onto land, as the case may be.

So yeah, they now think that different groups of animals may have actually gained and then lost the ability to gallop. So that’s fascinating. We’re talking about a pre-vertebrate fish-like creature from 450 million years ago. And so the question is, why did some animals give up the ability to gallop? So scientists will be trying to answer that question next.

IRA FLATOW: Well, I’m still getting over fish galloping. So thank you, Rachel.

RACHEL FELTMAN: Thanks, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: Have a good weekend.

RACHEL FELTMAN: You, too.

IRA FLATOW: Rachel Feltman, Executive Editor at Popular Science.

Copyright © 2022 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

As Science Friday’s director and senior producer, Charles Bergquist channels the chaos of a live production studio into something sounding like a radio program. Favorite topics include planetary sciences, chemistry, materials, and shiny things with blinking lights.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.