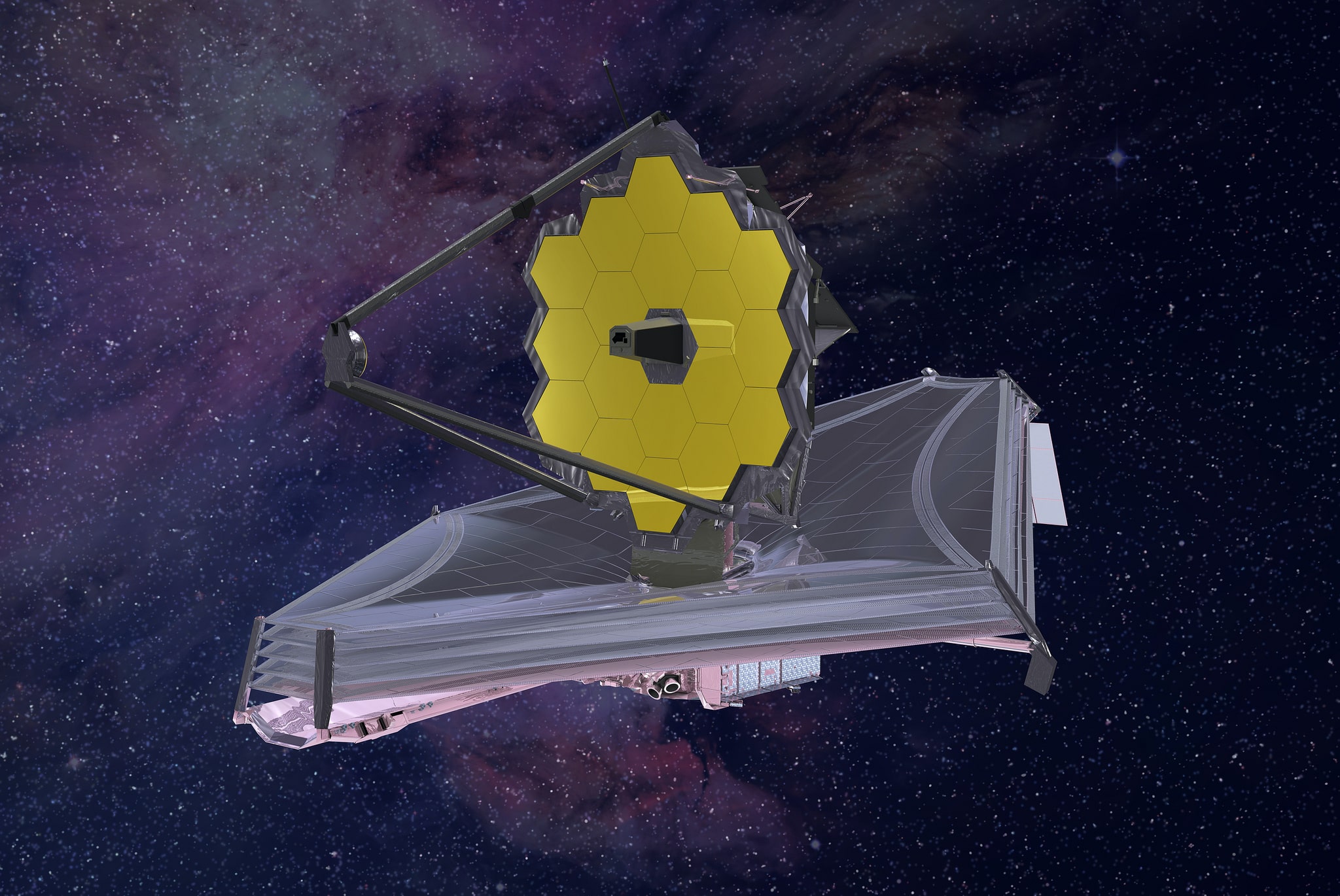

Webb Telescope Arrives To Its Final Home In Deep Space

6:07 minutes

After weeks of travel, the James Webb Space Telescope, or JWST, moved into its final orbit this week. Following a Christmas day launch, the spacecraft has spent a month in transit, deploying its solar array, unfolding its heat shield, and unpacking its hexagonal mirror segments. On Monday, the craft fired its engines to brake into a circular orbit around a point in space known as L2, where astronomers hope it will operate for at least 10 years.

Amber Straughn, an astrophysicist at the Goddard Space Flight Center and Deputy Project Scientist for James Webb Space Telescope Science Communications, joins guest host Miles O’Brien to talk about the telescope’s journey to L2. Straughn explains what will need to happen in the months ahead to fine-tune the mirrors and commission the science instruments on board before the telescope takes its first science images sometime this summer.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Amber Straughn is an astrophysicist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center and Deputy Project Scientist for James Webb Space Telescope Science Communications.

MILES O’BRIEN: For the rest of the hour, the James Webb Space Telescope– it arrived at its destination this week after launching Christmas Day. It was an eventful month for the team as the telescope went through a complicated origami-like unfolding. Joining me now for an update on how it all went and a look at how the mission will unfold from here is Dr. Amber Straughn. She’s an astrophysicist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, and serves as the deputy project scientist for the James Webb Space Telescope science communications. Welcome back to Science Friday, Amber.

AMBER STRAUGHN: Thank you. It’s great to be here. It’s been a pretty exciting month.

MILES O’BRIEN: To say the least. What a week. Congratulations on the arrival. A lot happened in the month since launch. Bring us up to date on what happened and how it happened.

AMBER STRAUGHN: So of course, we had a beautiful, spectacular, amazing– all the adjectives– Christmas morning launch. And the launch itself was super efficient. That means that we have a lot of fuel, actually– more fuel than we expected. So that was first part– we had an awesome launch. And then, of course, came these two weeks of intense, never done before deployments in space.

So that was a really sort of stressful couple of weeks for those of us working on the mission. But again, it’s all good news. The deployments went also almost perfectly. And then, of course, just earlier this week, on Monday, we had this final engine burn, which inserted JWST into its final orbit– it’s sort of home in space a million miles away. So wow– it’s been an eventful month.

MILES O’BRIEN: Walk us through all the things that could have gone sideways over the past month. There were a lot of– in space parlance– single-point failures to worry about right.

AMBER STRAUGHN: There were hundreds of single point failures. And that was really just necessary to build a telescope like this. It’s so huge, it had to be folded up to put into the rocket to launch it, and then that process of unfolding the telescope in space, and a lot of those hundreds of single-point failures, were involved in the unfolding of this giant tennis court-sized, five-layer sunshield. Again, everything went so well. It’s been fun to watch.

MILES O’BRIEN: And without that giant, tennis court-size sunshield, you’re pretty much out of business because on one side of it, it’s going to be over 200 degrees Fahrenheit. On the other side, almost getting close to absolute zero, which is really important if you’re looking for faint signatures of heat in the distant cosmos.

AMBER STRAUGHN: Yeah, the sunshield was absolutely critical for this mission. If the sunshield had not unfolded, we would not have had a telescope.

MILES O’BRIEN: I’m Miles O’Brien, and this is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. Let’s talk about the place in space where Webb is– Lagrange Point 2. Now this is a spot where the gravitational pull of the sun and the earth-moon system cancel each other out in a way that the Space Telescope orbits with the Earth all around the sun. Why is that an advantage? Why did you go that far out– almost a million miles?

AMBER STRAUGHN: So it turns out that this is a really good place to put spacecraft for the reason you’ve just described. We can put it out in that part of space, and because of the combined gravitational effects of the sun and the Earth, spacecraft will sort of stay there and travel along the orbit around the sun along with the Earth.

This is great for JWST because it’s really cold in that part of space, and we need the telescope to be very cold. Also, the telescope can stay in this sort of orbit around the L2 point with minimal fuel consumption, which is also very important. And also, it enables us to have constant, easy communication back to Earth. It’s always in a straight line from Earth. You can think of it as being straight up in the midnight sky.

MILES O’BRIEN: All right, let’s talk about this mirror, which is actually 18 mirrors that all have to line up with precision that is hard to grasp, actually.

AMBER STRAUGHN: Yeah, the next three months of this telescope’s commissioning process involves this process of aligning those 18 mirror segments. What we’ll do is take an image of a bright star, and the first image of that star– it’ll be 18 separate images. Perhaps even less– we don’t quite know what we’re going to see the first time. But the point is that we’re trying to get that star into the field of view of the telescope. And then, by tweaking each individual mirror segment, we’ll figure out which star image aligns up with each segment. And by that iterative process, over about three months, we’ll be able to focus this mirror into really a perfectly smoothly-shaped mirror to take these awesome images of the cosmos that we expect later this summer.

MILES O’BRIEN: OK, everybody wants to know– what’s the first target? What’s the first picture going to be?

AMBER STRAUGHN: The first images that we’ll take– the first science images, the pretty pictures so-to-speak– won’t be taken until the very end of this remaining five months of commissioning. There are a bunch of different targets that we– the possibility of taking, but I can’t tell you what they are.

MILES O’BRIEN: You’re being cagey with me Amber, come on.

AMBER STRAUGHN: I don’t even know what they are. There are not many people that know that know what those targets are.

MILES O’BRIEN: This is on a need-to-know basis. This is compartmentalized. Wow.

AMBER STRAUGHN: It’s going to be a big surprise. And I tell you what– it’s going to be worth the wait. I cannot wait to see these first images this telescope is going to deliver. It’s going to be awesome.

MILES O’BRIEN: Dr. Amber Straughn is an astrophysicist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, and she serves as the deputy project scientist for the James Webb Space Telescope science communications. Thanks for joining me.

AMBER STRAUGHN: Thank you for having me.

Copyright © 2022 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

As Science Friday’s director and senior producer, Charles Bergquist channels the chaos of a live production studio into something sounding like a radio program. Favorite topics include planetary sciences, chemistry, materials, and shiny things with blinking lights.

Miles O’Brien is a science correspondent for PBS NewsHour, a producer and director for the PBS science documentary series NOVA, and a correspondent for the PBS documentary series FRONTLINE and the National Science Foundation Science Nation series.