The Ivory-Billed Woodpecker Debate Keeps Pecking Away

11:58 minutes

Every so often, there’s a claim that the ivory-billed woodpecker is back from the dead. Pixelated videos go viral, blurry photos make the front page, and birders flock to the woods to get a glimpse of the ghost bird.

Last week, a controversial paper claimed there’s reason to believe that the lost bird lives. The authors say they have evidence, including video footage, that the bird still flies. The paper is ruffling feathers among the birding and research community.

A recent peer-reviewed paper included this video as evidence that the ivory-billed woodpecker is still alive. A small bird darts across the bottom of the frame from left to right.

This debate has been going on for decades, but the American Birding Association categorizes the bird as “probably or actually extinct,” and its last verified sighting was in 1944.

So is it any different this time? And what do we make of the claims that keep cropping up?

Guest host Flora Lichtman talks all things ivory-billed with Michael Retter, editor of the magazines North American Birds and Special Issues of Birding, from the American Birding Association.

For more, listen to Lichtman’s NPR segment about the bird from 2011.

Michael Retter is editor of the magazines North American Birds and Special Issues of Birding for the American Birding Association. He’s based in Fort Worth, Texas.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: This is Science Friday. I’m Charles Bergquist. I’m a producer here at SciFri.

FLORA LICHTMAN: And I’m Flora Lichtman, host and managing editor at Gimlet Media. And today we are filling in for Ira Flatow.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: Later in the hour, scientists are trying to crack the code of what causes chronic pain and how it’s processed in the brain. And they’ve made exciting progress.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Plus, finding solace in grief by looking to the stars. But first, bird drama. Is the ivory billed woodpecker alive? This giant woodpecker has been classified by the American birding association as probably or actually extinct. Its last verified sighting was in 1944. But last week, a controversial new paper claimed there’s reason for hope.

The authors say they have evidence the bird still flies, including a new video. And the paper is ruffling feathers because there have been claims like this in the past.

SPEAKER 1: The ivory Bill’s Resurrection is an amazing story.

SPEAKER 2: We just saw an ivory bill together, the first people in over 60 years.

SPEAKER 1: The ivory billed woodpecker was reportedly sighted in a Federal Wildlife Refuge.

SPEAKER 3: Our viewers sent in this video of an ivory billed woodpecker.

SPEAKER 2: That bird could be here–

FLORA LICHTMAN: Pixelated videos go viral. Blurry photos make the front page. And birders flock to the woods to get a glimpse of the ghost bird. And then nothing. Is it any different this time? Here with the lowdown is Michael Redder, editor of the magazines North American Birds and Special Issues of Birding from the American Birding Association. He’s based in Fort Worth, Texas. Michael, welcome to Science Friday.

MICHAEL REDDER: Hi, Flora. Thanks for having me.

FLORA LICHTMAN: OK, Michael, you’re a birder. You’ve got 3,000 bird species on your life list. You’ve written several books about birds. I want your hot take. Do you think the ivory billed woodpecker is alive?

MICHAEL REDDER: Unfortunately, I don’t think so, no.

FLORA LICHTMAN: All right, before we get into all that drama, I want to just hear a little bit about the bird. So tell me about the ivory billed woodpecker.

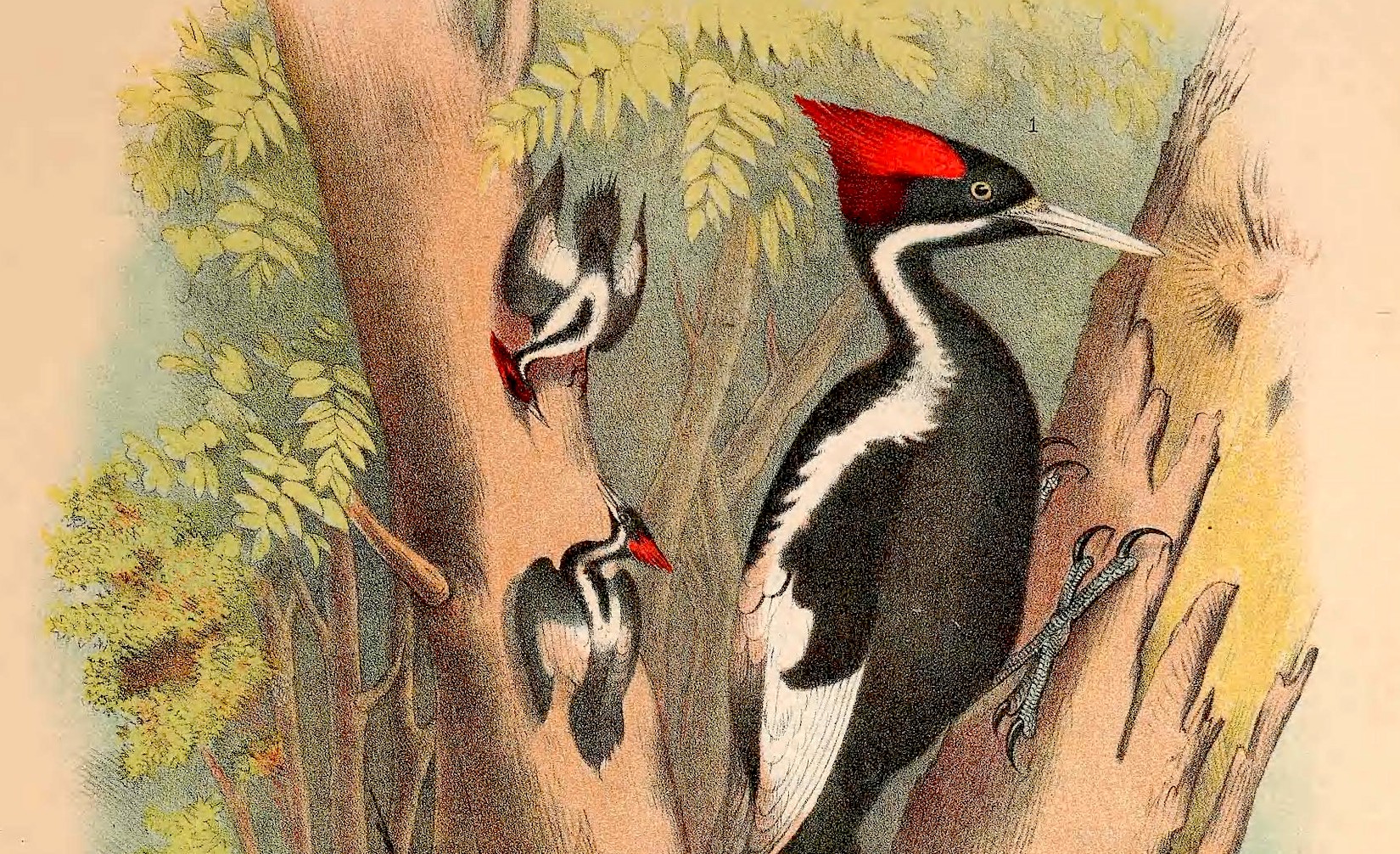

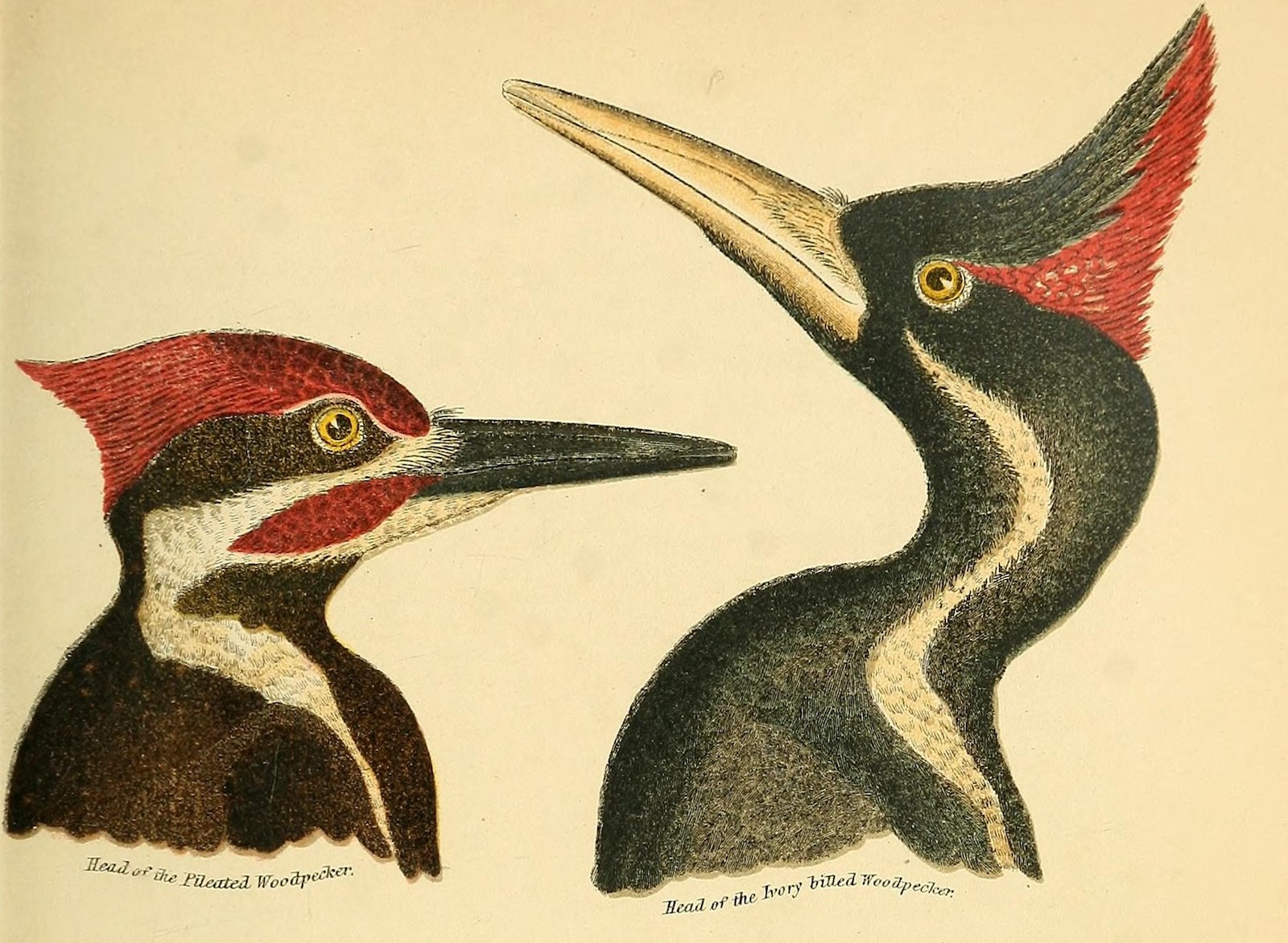

MICHAEL REDDER: OK, so it was the largest species of woodpecker that lived in North America, this large, mostly black bird with big white patches on the wing and a white stripe up the side of the neck. The male had a big red crest. And the female had a kind of cool Black crest that curled forwards. And they both had a big pale yellow bill and pale eye, very striking bird, very loud.

They banged on dead, empty trees so that it would echo across the land. And they also had loud calls, vocal calls that they would use. So very loud, conspicuous birds.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Can you give me your best impersonation?

MICHAEL REDDER: Oh, gosh, well the striking on the tree the double tap is characteristic of birds in that genus, which still exist in Latin America. So I’ve heard them, and it’s just a loud bang, bang on a tree. But they also have a vocal call that sound– if you’ve ever heard an orchestra warming up or a child learning to play the clarinet, there’s kind of this squeaky sound that a clarinet can make.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Delightful.

MICHAEL REDDER: And they sounded kind of like that.

FLORA LICHTMAN: So majestic.

MICHAEL REDDER: Yes.

FLORA LICHTMAN: And where did the bird live?

MICHAEL REDDER: So ivory billed woodpeckers were restricted to kind of bottomland, swampy forests in the Southeastern United States and also in Cuba.

FLORA LICHTMAN: OK. And what happened to the population?

MICHAEL REDDER: Well, people happened. People hunted them. Scientists collected them to put them in drawers in universities. And we cut down all the trees that they depended on to live.

FLORA LICHTMAN: So this new paper includes photos and videos from researchers that they say is evidence that the bird is alive. What do you see in those images?

MICHAEL REDDER: I see either things that are not identifiable, or I see the superficially similar pileated woodpecker.

FLORA LICHTMAN: What is the difference between the ivory billed and the pileated woodpecker?

MICHAEL REDDER: The pileated woodpecker is mostly black. And it has a white patch in the wing when it spreads the wing, kind of out towards the tip. And it has white under the wing when it flies. And it has a shorter, dark bill.

Ivory billed woodpecker, when it’s perched, when it’s not flying, when it’s hanging on the side of a tree has big white patches on top of the wing and white stripes that go up the back and up the side of the head. And it has the big, pale yellow almost white bill and a white eye. And the ivory billed woodpecker is also much larger.

FLORA LICHTMAN: What would compelling evidence look like to you?

MICHAEL REDDER: It would look like a decent photo or video. And those are so easy to get these days because everybody has a camera in their pocket. And this is not a bird that hides. It’s not only loud and conspicuous and flashy, but it lives in forests that don’t have leaves on them for half of the year.

Scientists are going into primary rainforest on two-week treks. And they’re finding tiny brown birds that hide and don’t like to come out. And they’re coming back with incredible photos and videos of these things. And it’s just it’s incredibly improbable that this big flashy bird that lives in the United States, that we somehow can’t get a good photo of it. It just defies reason to me.

FLORA LICHTMAN: The thing that strikes me is that this is a peer-reviewed paper, right? These are reputable ornithologists making these claims. What is happening?

MICHAEL REDDER: In general, I would say that most ornithologists are not experts on bird identification. They are experts in their very narrow particular field of study.

And to give you an instance, my husband is an expert on the genetics and genomics of a couple species of salmon. But if you put them in front of him on a table, he wouldn’t know what they were.

And in my experience, a lot of ornithologists, not all, are like that with birds. They might know how many eggs on average a house wren tends to lay in its nest. But if a female red-winged blackbird landed in front of them, they might not know what it was just because they haven’t studied that.

And there’s nothing wrong with that. But ornithologist doesn’t automatically mean bird identification expert.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Well, why do you think it got through peer review?

MICHAEL REDDER: I don’t know. I can’t tell you. But I would be surprised if there were many bird identification experts as the reviewers, if any.

FLORA LICHTMAN:

CHARLES BERGQUIST: When you saw this news, what was your reaction?

MICHAEL REDDER: Oh, OK, here we go again. And then I went on about my day and was hoping that I wouldn’t hear about it again.

[LAUGHTER]

FLORA LICHTMAN: I mean, and this has happened before, right? There have been other claims?

MICHAEL REDDER: Yes, it’s happened before, most spectacularly in 2005 when it was announced with the Department of the Interior. And then shortly thereafter there was a paper released, I want to say in the same journal, by David Sibley and some other authors that debunk the claims of the first paper.

FLORA LICHTMAN: The famous bird identification book author David Sibley?

MICHAEL REDDER: Right, right. And I don’t know if we’ll see that again. I mean, I think at this point, the people who are convinced it doesn’t exist, they don’t– in some ways, they don’t think it’s worth their time to rebut it because it’s been done, and it’s been done, and it’s been done.

And it’s almost becoming like Bigfoot or the Loch Ness Monster.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: Do you think there’s any harm in people keeping the hope?

MICHAEL REDDER: On like a personal, human level, perhaps not. I mean, I hope too. I really want this to be true. It would be so amazing both for those of us who would like to experience the bird but also the bird itself and its ecosystem because it played an important role in it.

But there is a harm to other ecosystems and other birds when we funnel money into the protection of a species that’s already extinct. Then we’re neglecting the protection of species that aren’t yet extinct because money is finite.

FLORA LICHTMAN: So even though many bird organizations say the ivory billed woodpecker is extinct, the US Fish and Wildlife Service lists the bird as Critically Endangered. And if that agency declares that the bird is extinct, which it’s expected to do, that would remove federal protections and funding. So I’ve heard that some folks are like, well, why not just– on the off chance the bird is alive, why take away hope? Because we don’t want to lose that protection and funding. What do you make of that?

MICHAEL REDDER: I think that removing protection for something that doesn’t exist isn’t very consequential. But if there’s one out there, yes, having protection for it would be helpful. But the funding is problematic.

Funding the protection of something that is extinct means that we’re not funding protection of things that aren’t yet extinct but will go extinct because we’re not funding them. But on the other hand, I mean, if the US government removes protection from ivory billed woodpecker and one appears, I have to believe that it would gain protection again in the blink of an eye.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: Is there another woodpecker that is facing extinction?

MICHAEL REDDER: Well, there’s a woodpecker right here in the United States in the Southeast called the red-cockaded woodpecker that is– I don’t remember if it’s still endangered, but it definitely needs our help because it depends on pine trees in the kind of natural ecological regimen, which is frequent fires and not cutting down dead and diseased trees because those are the trees that it uses to nest. So without our help, the red-cockaded woodpecker would be in some trouble.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Tell me about this woodpecker. Where does it live? What does it look like?

MICHAEL REDDER: It lives in the Southeastern United States in pine forests, in open pine forests. And it’s black and white, black and white bars. And the male has a tiny little red Patch on the head that is maybe just a couple of feathers and is extremely hard to see. That’s the cockade and the red cockaded woodpecker.

And it nests in colonies, which is weird for a woodpecker. So you might have 10 or 12 pairs in an area. And they only build their nests in the trees with– in the diseased trees that are oozing sap. And it’s thought that the sap that covers the trees helps protect them from predators trying to get into the nest.

FLORA LICHTMAN: This seems like something that people could put on their life list.

MICHAEL REDDER: Oh, absolutely.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: I would love to see one of those woodpeckers.

MICHAEL REDDER: Yeah. And for birders, one of the things that makes them maybe a little easier to find than they ought to be is that since they are rare and we are trying to manage and protect them, usually there are white rings spray painted around the trees that they have nests in.

So when you’re in their habitat and you see a tree with a white ring on it, there’s probably a red-cockaded woodpecker nest in it or nearby.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: I can’t let you go without asking you for your favorite woodpecker fun fact.

MICHAEL REDDER: They have incredibly long tongues that they roll up in a spiral kind of around their brains.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Come on.

MICHAEL REDDER: And surrounding that, their brain is encased in liquid. So that when they hit a tree with all that force, their brain is suspended and liquid and doesn’t get banged into their skull. So their heads are pretty remarkable.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Whoa. And the tongue is for grabbing whatever is in the hole that they just drilled?

MICHAEL REDDER: Yeah, that’s exactly right.

FLORA LICHTMAN: This is what I’m going to think about the next time I see a downy woodpecker at my feeder.

MICHAEL REDDER: That’s great.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Michael, thank you so much for joining me.

MICHAEL REDDER: It’s been my pleasure. Thank you for having me.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: Michael Redder, editor of the magazine’s North American Birds and Special Issues of Birding from the American Birding Association. He’s based in Fort Worth, Texas.

Copyright © 2023 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Rasha Aridi is a producer for Science Friday and the inaugural Outrider/Burroughs Wellcome Fund Fellow. She loves stories about weird critters, science adventures, and the intersection of science and history.

Flora Lichtman is a host of Science Friday. In a previous life, she lived on a research ship where apertivi were served on the top deck, hoisted there via pulley by the ship’s chef.