U.S., Russia, and Canada Continue Collaboration On Wild Salmon Survey

8:16 minutes

This article is part of The State of Science, a series featuring science stories from public radio stations across the United States. This story, by Eric Stone, was originally published on KRBD.

This article is part of The State of Science, a series featuring science stories from public radio stations across the United States. This story, by Eric Stone, was originally published on KRBD.

Tensions continue to simmer between Moscow and Washington in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

In many respects, the divide between East and West is deepening: Oil companies are canceling partnerships with Russian firms. State legislators are calling for the state’s sovereign wealth fund to dump Russian investments. President Joe Biden announced Tuesday the U.S. would close its airspace to Russian aircraft.

But the United States and Russia are continuing to work together on at least one issue: salmon.

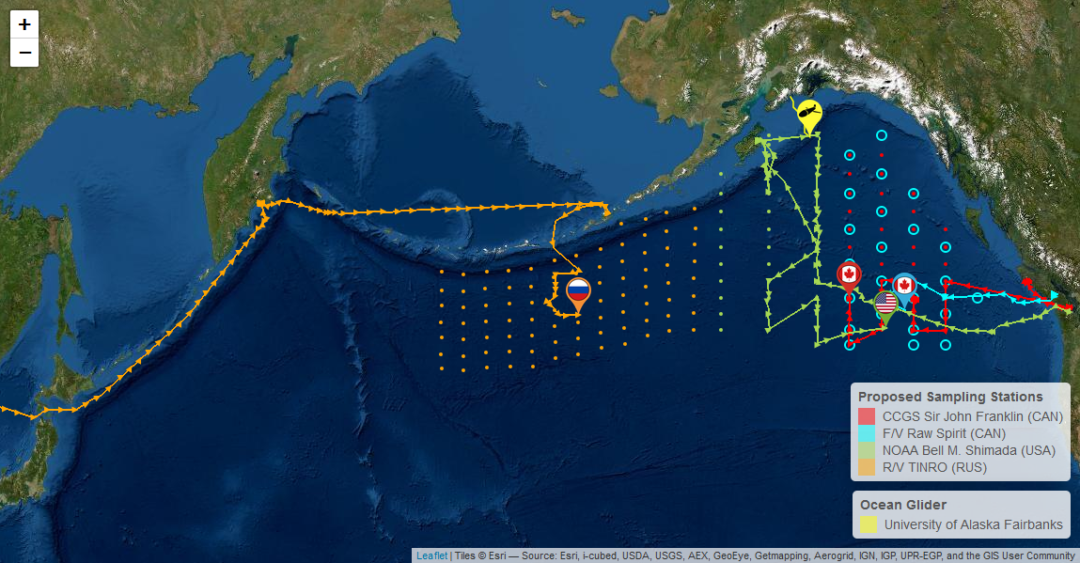

There’s a map scattered with orange, green, blue and red dots spanning most of the North Pacific above 46 degrees latitude.

On the map are three flags of Arctic nations: the U.S., Canada and the Russian Federation.

“This interaction between the countries in this is really something that has never happened to this scale before,” said Mark Saunders, the executive director of the five-country North Pacific Anadromous Fish Commission.

He’s talking about the 2022 Pan-Pacific Winter High Seas Expedition.

Vessels from both sides of the Pacific are braving gale-force winds and 13-foot seas as they crisscross the ocean from the edge of the Aleutian Chain to the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

All in the name of research on challenges to wild salmon runs that are important to people on all sides of the north Pacific Rim.

Last year, the chum salmon run on the Yukon River collapsed.

“This past summer, the Yukon River did not fish for food. Zero,” said Mike Williams Sr. He’s the chair of the Kuskokwim Inter-Tribal Fish Commission, an organization that manages and researches fisheries using a combination of traditional knowledge and Western scientific methods.

Never before had so few fish swum up the nearly 2,000-mile river. Regulators closed all fishing on the Yukon to preserve what little of the run remained.

Williams says in recent years, he’s watched runs on the Kuskokwim dwindle, too. In the past, he says fishing was relatively unrestricted: Residents would return to their fish camps shortly after the ice on the river broke up in the spring.

But in recent years, he says residents have had to wait until June — long after breakup — to start stockpiling the essential staple.

“We depend on the salmon to sustain us through the winter, and we’re very concerned about the returns of our salmon in all of the rivers in Western Alaska” Williams said in a phone interview Wednesday.

It’s not clear what was behind the collapse. The Inter-Tribal Commission — and the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, for that matter — spend most of their effort studying what happens in freshwater. But that’s just a small part of a salmon’s life.

“The salmon spawn in our headwaters, they go down to the ocean, and something happens in the ocean,” Williams said.

And it’s not just Western Alaska that’s struggled with salmon runs in recent years — in Southeast, Chinook runs from Haines to Ketchikan are listed as stocks of concern. Salmon fishing on the Unuk River has been banned outright for years.

Some, including Williams, say too many salmon in the Bering Sea and the North Pacific are pulled out of the ocean as bycatch from trawlers that scrape the seabed for sole and flounder. Others say fish from hatcheries all over the north Pacific Rim are outcompeting native fish. Some say climate change is affecting the food web — or a combination of all these factors.

But one thing is clear: something is happening to chum and Chinook salmon in the open ocean.

“We know that a lot of the poor survival for chum and other salmon is related to the marine environment,” Saunders, of the North Pacific Anadromous Fish Commission, said Tuesday from his home office on Vancouver Island.

There’s quite a bit known about how the ocean is changing, “but you need to know where the fish are and have actually had your hands on them, and understand how they’re interacting with the environment,” Saunders said.

“I think a lot of that is a large black box — in particular, this winter period we know very little about,” he added.

He says the goal of the survey — the largest ever conducted — is to shine some light in that black box.

Scientists are hoping to map out the distribution of salmon across the North Pacific using new DNA techniques developed over the past decade or so to understand where salmon interact with predators, prey and each other — not to mention a generally warmer, more acidic ocean.

“And the big question is, how is the changing North Pacific Ocean affecting our salmon? And improving our ability to understand how that change is going to impact people and fish and fisheries into the future,” he said.

That brings us back to the map.

Earlier this winter, ships from the U.S., Canada and Russia set sail for the North Pacific. Each is assigned its own area to sample: The U.S. and Canada are tackling areas in the Gulf of Alaska and west of British Columbia, and a vessel from Russia is surveying an immense swath of ocean spanning areas south of the Alaska Peninsula all the way out the Aleutian Chain southwest of Adak.

The Russian vessel’s survey work started late last month — it actually tied up in Dutch Harbor a day after Russian troops started their assault on Ukraine’s capital, Kyiv. Unalaska’s port director told KRBD the visit was tightly scrutinized by U.S. border agents.

Alaska’s chief salmon scientist, Bill Templin, says a few thoughts crossed his mind as he watched the invasion unfold.

“My first concerns were for the people of Ukraine,” Templin said by phone Wednesday. “But then when I walked into my office and I sat down, I was thinking, Oh, OK, so what does this mean?”

He says it’s not the first time international tensions have come up in his work with the five-country commission. He recalls Russian scientists including islands disputed with Japan on maps of salmon stocks — all in good fun, as he recalls it.

“The first two years, they got it past me, and the Japanese had to come over and correct me very politely,” he said.

But this is more tension than usual.

Saunders, the head of the anadromous fish commission, says an American scientist was scheduled to board the Russian vessel to allow it to survey within the 230-mile U.S exclusive economic zone.

That didn’t happen. And that means the Russian research vessel can’t work close to the Aleutian Chain, where some salmon are thought to spend the winter. Templin says that means salmon activity within that zone will remain a blank spot for now.

“It doesn’t ruin the results. It’s not a failure — but it is going to limit what we get,” he said. “And it’s taken years to get this winter coordinated, so it’s a little disappointing.”

But Templin says scientists from Japan, Canada, South Korea, Russia and the United States have always put their work first, and their political leaders’ policies second. And he says that’ll continue.

“The salmon all go to the same place. So they’re all grazing in the same field, so to speak. For all of us to work together to understand what’s happening out there, and the way it affects our nations, is — I think it’s a pretty huge deal,” he said. “And I’d hate to see it go away.”

So far, geopolitical tensions haven’t overshadowed the need for cooperation — at least, not when it comes to preserving wild salmon.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Eric Stone is the news director at KRBD in Ketchikan, Alaska.

IRA FLATOW: Now it’s time to check in on the state of science.

SPEAKER 2: This is KER–

SPEAKER 3: For WWNO–

SPEAKER 4: St. Louis Public Radio–

SPEAKER 5: Iowa Public Radio News–

IRA FLATOW: Local science stories of national significance. A little over a month ago, scientists from the US, Russia, Canada, Japan, and South Korea embarked on a collaborative scientific survey to track wild salmon in the North Pacific Ocean. Then Russia invaded Ukraine, setting in motion, as you can imagine, a substantially more tense political situation to navigate.

Yet despite the tension, scientists have opted to continue to collaborate in pursuit of understanding the recent fluctuations in the wild salmon population. Joining me now to talk about his reporting on the topic is Eric Stone, News director of KRBD, based in Ketchikan, Alaska. Eric, welcome to Science Friday.

ERIC STONE: Hi, thank you for having me.

IRA FLATOW: You’re welcome. Before we get into the details of this research project, let’s start with some basics of a salmon’s life cycle, OK? For those of us who might need a refresher, what is the salmon Run

ERIC STONE: OK, so salmon spend part of their lives in freshwater and part of their lives in saltwater. They’re what’s called an anadromous fish. And basically what happens is they hatch from eggs in these rivers, and then they swim out to sea after fattening up just a little bit.

And they spend a little while out there, generally two to five years, depending on the species, eating things like herring and squid and all kinds of stuff. And then towards the end of their lives, they swim back up the river to deposit eggs and fertilize the eggs and start the cycle over. And they can swim sometimes more than 2000 miles, in at least one river in Alaska.

IRA FLATOW: Wow.

ERIC STONE: And as they swim up the river, they don’t eat. It’s remarkable. And in Western Alaska, in particular, and you know frankly all over Alaska, the salmon are vital sources of food for Indigenous people. People catch them in nets and fish wheels. And people catch them with rods and reels, as well.

It’s an important cultural phenomenon. People construct these things called fish camps, where they go and gather their food source for the winter and catch all these salmon. And not to mention, commercial salmon fishing is a huge industry here in Alaska that employs lots of people. It also feeds people all over the United States and all over the world.

IRA FLATOW: And so there are lots of rivers in Alaska where the salmon are running, and maybe they fluctuate about the number of salmon that are migrating?

ERIC STONE: That’s right. Yeah, so the salmon runs on these various rivers, they fluctuate in weird ways, and we don’t totally know why. So I’ll give you a few examples. Pink salmon harvest here in southeast Alaska were among the lowest in decades in 2020, and then in 2021 pink salmon beat the forecast by a good bit.

IRA FLATOW: Wow.

ERIC STONE: King salmon stocks all over southeast Alaska are also in trouble. Like fishing for any salmon near the mouth of a major river here in Ketchikan has been banned outright for years. But it’s really in western Alaska where the salmon runs have been in crisis most recently.

So in 2020, the Yukon River chum salmon run faltered. Chum salmon as a species of salmon, one of the five pacific salmon species. And then in 2021, the run totally collapsed. There were so few fish that people were not allowed to fish, and that’s a large component of how people feed themselves. Authorities had to ban fishing up and down the river to preserve what little of the run remained. And it was a massive shock to people who depend on salmon, go to great lengths to replace it.

One resident told Olivia Ebertz of radio station KYUK in that area that he took his river-going skiff into the dangerous waves of the Bering Sea. But runs on the Kuskokwim River have also been faltering. Mike Williams Senior, of the Kuskokwim Inter-Tribal Fish Commission– it’s an organization that manages and researches salmon in the area– told me that he’s worried about runs all over the region.

MIKE WILLIAMS: We depend on the salmon to sustain us through the winter, and we’re very concerned about the returns of our salmon in all of the rivers in western Alaska.

ERIC STONE: And while the salmon run collapsed in that area on the Yukon River and is trending down on the Kuskokwim River, that same year in 2021, the sakai salmon run in Bristol Bay, which is a giant commercial fishery, that set a new record.

IRA FLATOW: That’s amazing. So what you want to know, and what the scientists want to know, is why this wild fluctuation is going on.

ERIC STONE: Yeah, that’s right. And the problem is, we don’t know. Most of the effort that’s gone into studying salmon has been focused on what happens in freshwater, you know where they reproduce.

IRA FLATOW: Right.

ERIC STONE: Scientists think that issues happen in the open ocean while they’re out fattening up. There has been some research, and there are a few theories. I’ll run through a couple of those. One is bycatch, the idea that salmon at sea are getting scooped up in the nets for sole and flounder or pollock, accidentally caught, more or less.

Another is that hatcheries– basically there are these facilities where salmon are raised from eggs into juvenile salmon, and they’re artificially enhancing wild populations. And one of the theories is that those artificially enhanced populations are out-competing wild salmon.

And then the third theory is that climate change is messing with the food web. That’s warmer ocean, more acidic. So we know the ocean is changing but not as much how the salmon are reacting to the condition. It’s kind of a big black box.

IRA FLATOW: What is the 2022 Pan-Pacific Winter High Seas Expedition? And how will it help test some of these theories?

ERIC STONE: So basically, it’s a giant effort to study what happens in the black box of the open ocean during the winter. So vessels from three of the five countries you said at the top, the US, Canada, and Russia, they’re out canvassing the North Pacific as we speak right now. They’re putting a net down to see what kind of salmon there are.

And the reason they’re doing it during the winter is that winter is an especially tough time for salmon. There’s not as much food, and this is where it’s hypothesized that most of them die. So this is a good time to figure out what’s going on with the population. So the idea is to give a better idea of how salmon are reacting with predators, with each other, with ocean conditions, kind of shine some light in that black box.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. Given the current political situation, is the survey going on as planned? Has there been any talk about not cooperating or eliminating Russia from this survey?

ERIC STONE: So I haven’t heard any talk about cutting Russia out. They’re doing a massive amount of work on this subject. And the survey is still going ahead. There have been some modifications. One an interesting thing is that one of the survey vessels from Russia, the one that’s covering an area that goes from about the middle of the Alaska Peninsula, so it’s kind of even with the west coast of Alaska, all the way out to the– almost the end of the Aleutian chain, they actually tied up in Dutch Harbor– that’s the Deadliest Catch port– a day after Russians invaded Ukraine and started their assault on Kyiv.

And now what happened is that a US-based scientist was not allowed to board. So what happens now is that Russians are not allowed to survey within the 230 mile exclusive economic zone of the United States, basically waters close to the United States. And that is going to have impacts on the results of the study. Doesn’t mean the mission is a failure, according to one of the scientists I talked to, but it means that salmon activity within that area near the Aleutian chain is going to remain a mystery for now.

So I spoke with Bill Templin. He’s Alaska’s chief salmon scientist. And he told me the five country commission has worked together in times of tension before. He said some Russian scientists actually included disputed islands in some salmon stock maps, and the Japanese had to politely ask him to change the maps. So he said that was all in good fun, but this is quite a bit more tension than usual. Even so, Templin told me that the salmon scientists are used to putting their work first and their political leaders policies second.

BILL TEMPLIN: The salmon all go to the same place. And so for all of us to work together to understand what’s happening out there and the way it affects our nations, I think it’s a pretty huge deal. And I’d hate to see it go away.

ERIC STONE: And you can actually track all of these vessels. There are four of them from the US, Canada, and Russia. They’re all on a map at yearofthesalmon.org.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. I think I’m going to do that. Thank you, Eric. Great report.

ERIC STONE: Oh, thank you very much for having me. It was really a pleasure to be on.

IRA FLATOW: Eric Stone, News Director of KRBD, based in Ketchikan, Alaska.

Copyright © 2022 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Kathleen Davis is a producer and fill-in host at Science Friday, which means she spends her weeks researching, writing, editing, and sometimes talking into a microphone. She’s always eager to talk about freshwater lakes and Coney Island diners.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.