InSight Settles In On Mars

7:19 minutes

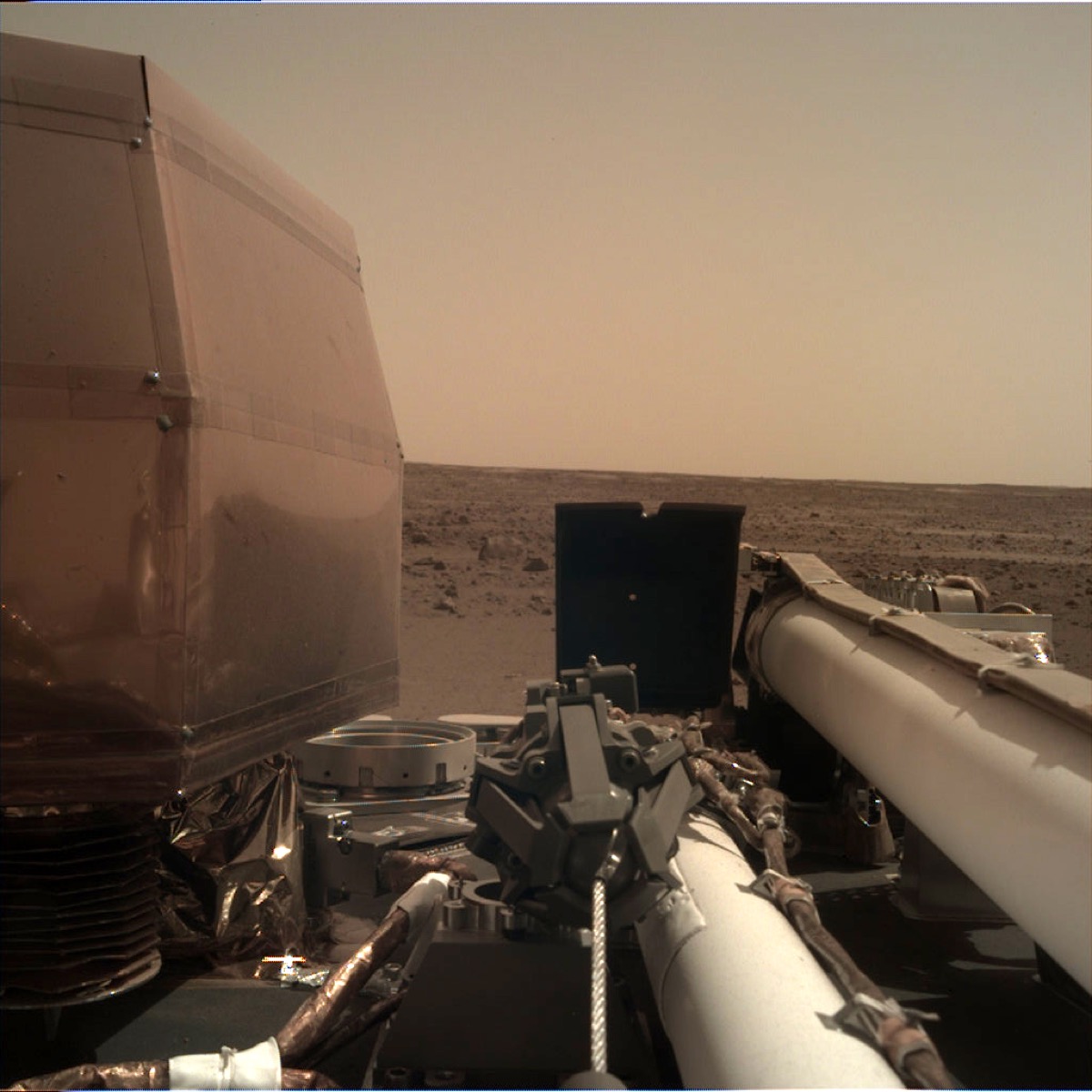

This Monday, Mars fans rejoiced as NASA’s lander Mars InSight successfully parachuted safely onto the large, flat plain of Elysium Planitia. In the days that followed, the lander successfully has deployed its solar panels and begun to unstow its robotic arm. InSight scientists will use images gathered by the lander to evaluate where to position its scientific instruments. The landing also marked the debut of two tiny experimental CubeSats named MarCO, which helped relay data during the landing process.

Maggie Koerth-Baker, senior science editor for FiveThirtyEight, joins Ira to talk Mars InSight and other stories from the week in science, including a court battle over frog habitat, what lies beneath Antarctica, and an ion-powered plane.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Maggie Koerth is a science journalist based in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. A bit later in the hour, we’ll take the temperature of the latest National Climate Assessment. But first, on Monday, Mars fans rejoiced as Mars InSight stuck the landing on a large flat plain near the Martian equator. And in the days that followed, all signs are good. The lander has deployed its solar panels, has begun to un-stow its robotic arm. And scientists are planning where to place their instruments. Joining me now to talk about that space feat and other short subjects in science is Maggie Koerth-Baker. She’s a senior science reporter for FiveThirtyEight. She joins me from the NPR MPR Studios. Welcome back, Maggie.

MAGGIE KOERTH-BAKER: Hi, thanks for having me.

IRA FLATOW: This is kind of– you know, what’s the mission of this lander?

MAGGIE KOERTH-BAKER: Well, so, InSight– which is a tortured acronym for Interior exploration using Seismic Investigations Geodesy and Heat Transport– is designed to study geologic activity, or lack thereof, beneath the Martian soil.

IRA FLATOW: So it’s going to dig down into the soil with probes?

MAGGIE KOERTH-BAKER: Yeah. So you know how Earth has these plates of crust that move slowly crashing into each other, forming/reforming continents over millions of years? Well, it turns out, that Mars apparently doesn’t have any of that. You know, the planet seems to have been tectonically active in its ancient past, but it isn’t anymore. And nobody really knows why. No one knows what happened. They know that there are earthquakes on Mars. And InSight is going to measure some of those. But those aren’t even caused by plate tectonics there. Instead, they’re caused by the crust cracking as the planet’s interior cools and shrinks. And we don’t even know if the planet’s core is still molten, or if it’s solidified.

IRA FLATOW: Well, that’s exciting to find out. The landing was marked by a couple of tiny satellites that went along for the ride.

MAGGIE KOERTH-BAKER: Yeah, these little briefcase-sized cube sets that launched the same time as InSight, and traveled kind of alongside of it so that when it was landing, they were able to be flying by Mars and sending information back to Earth.

IRA FLATOW: So it’s not like relying on a satellite that already was in orbit, you have instant new satellites.

MAGGIE KOERTH-BAKER: Yeah, yeah. They could have relied on a satellite that was already in orbit, but that one was about to go around to the far side of Mars just as they were coming in. And then it would have been hours before they found out any information about it.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, I hate it when that happens. All right, moving back to Earth, on Wednesday, the US Supreme Court instructed the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals to figure out a definition of the word habitat.

MAGGIE KOERTH-BAKER: Yeah, so, this is interesting because I love esoteric things like this. This is this really narrow ruling in a much bigger case that’s likely going to end up determining the fate of this dusky gopher frog that once lived all across the American South, but is now confined to a single pond in Mississippi.

And back in 2012, the US government came up with this plan to designate some land in Louisiana as gopher frog habitat, give the animal a place to recover its numbers, and kind of let it grow there. But the people that owned the land and who wanted to develop that land sued. And the catch here, and what the Supreme Court case is focused on, is what habitat really means. Because no dusky gopher frogs currently live in Louisiana. In some ways, this designated habitat area isn’t even ideal for them, and you’d have to do some alterations just to kind of make it a place they could move into.

But expanding their range is critical to their survival. So the land, can it be a critical habitat legally controllable by the Endangered Species Act, if it’s not already a habitat? And that’s what the Supreme Court wants the lower courts to figure out now.

IRA FLATOW: Is a habitat a habitat if you have to make it a habitat?

MAGGIE KOERTH-BAKER: Yeah.

[LAUGHING]

There’s a limerick in here somewhere, but I’m not sure that I’m authorized to say those on air.

IRA FLATOW: And you’re saying this could have a wider impact for other habitats around.

MAGGIE KOERTH-BAKER: Well, presumably, it could, yeah. Because if we have a very narrow definition of what a critical habitat can be, that’s going to affect other species as well.

IRA FLATOW: And you have another story out this week about something that’s deep in my heart because I visited Antarctica many centuries ago– what lies beneath Antarctica. Because when you’re up there, you see 14,000 foot peaks. There’s a real continent under there, but there’s a mile of ice– you know, in some places, two miles. And so we’re finding out more now what’s really beneath the ice.

MAGGIE KOERTH-BAKER: Yeah. And what’s beneath the ice is kind of cool. So, it’s really hard to study the actual geology of Antarctica because, as you say, it’s under this mile thick layer of ice. But last week, The New York Times reported that scientists had used data collected by a European satellite that crashed to Earth in the past couple of years to effectively peer through that ice by measuring variations in the gravitational field.

And what they found is the remnants of at least three ancient continents that had all been kind of smushed together. One of them has a lot in common geologically with Australia. There’s another one that’s similar to India, and a third that’s probably ancient sea floor. And all three of these were once part of the supercontinent, Gondwana, that broke apart 160 million years ago.

IRA FLATOW: Wow, that is cool.

MAGGIE KOERTH-BAKER: Yeah.

IRA FLATOW: It was all one, Pangea, and Gondwana, was all great stuff. Finally, news of a science fiction-sounding airplane. Tell us about that.

MAGGIE KOERTH-BAKER: Yeah. So scientists at MIT have flown a plane on Earth using a technology that everybody thought would only work in space. And this technology is called an ion thruster. And essentially, you know how when you’re in a swimming pool, you can kind of push off the wall and you go forward, it’s kind of the same sort of idea– that you’re pushing a charged particle out the back of the craft, and that motion in one direction pushes the ship in the other direction.

And this is really cool, because it’s silent, it has no moving parts. There’s no engine. And we already use this technology in some small ways in space exploration. There’s a few deep space probes that do it. It’s kind of used for, effectively, parking, nudging spacecraft into place. But last week marks the first time that it worked on Earth, which is really weird, because our atmosphere is thick enough that that force of those little ionized particles shouldn’t be enough to push much of anything forward.

IRA FLATOW: But this was like a toy-sized plane, right? It wasn’t a big airplane.

MAGGIE KOERTH-BAKER: Right, not a regular big airplane, something more similar to like what you would fly with your kid in a park or like drone, even. But it did travel 200 feet at about 11 miles an hour. And it worked partly because the scientists redesigned everything to be as light as humanly possible, but also because they designed this new kind of ion thrust system where they are generating particles at the front of the plane, and then those particles are getting sucked back towards negatively charged filaments at the back of the plane. And at the same time, those particles are all sort of crashing into air molecules as they go, and that generates a wind. And the wind is the thing that’s getting the the plane up.

IRA FLATOW: 200 feet, 11 miles an hour. Was it flown at Kitty Hawk? No.

[LAUGHING]

MAGGIE KOERTH-BAKER: It was flown in a gym, basically.

IRA FLATOW: A lot different. Thank you, Maggie.

MAGGIE KOERTH-BAKER: Yeah, thank you.

IRA FLATOW: Have a happy holiday, if we don’t talk to you. Maggie Koerth-Baker, senior science reporter at FiveThirtyEight.

Copyright © 2018 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

As Science Friday’s director and senior producer, Charles Bergquist channels the chaos of a live production studio into something sounding like a radio program. Favorite topics include planetary sciences, chemistry, materials, and shiny things with blinking lights.