Laugh And Learn With The Ig Nobel Prizes

34:27 minutes

This year, even though many people may be still hesitant to gather together for the holidays, a Science Friday holiday tradition lives on—our annual post-Thanksgiving broadcast of highlights from the Ig Nobel Prize ceremony, now in its 31st first annual year.

Marc Abrahams, editor of the Annals of Improbable Research and master of ceremonies for the prizes, joins Ira to present some of the highlights from this year’s awards—from research into the microbiology trapped in the gum on the sidewalk to a transportation prize for scientists who discovered the best way to safely transport a rhinoceros long distances. (Dangle it upside down under a helicopter.) Tune in to hear about research involving the kinetics of crowds, the communications of cats, thoughts about the evolutionary history of human beards, and more.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

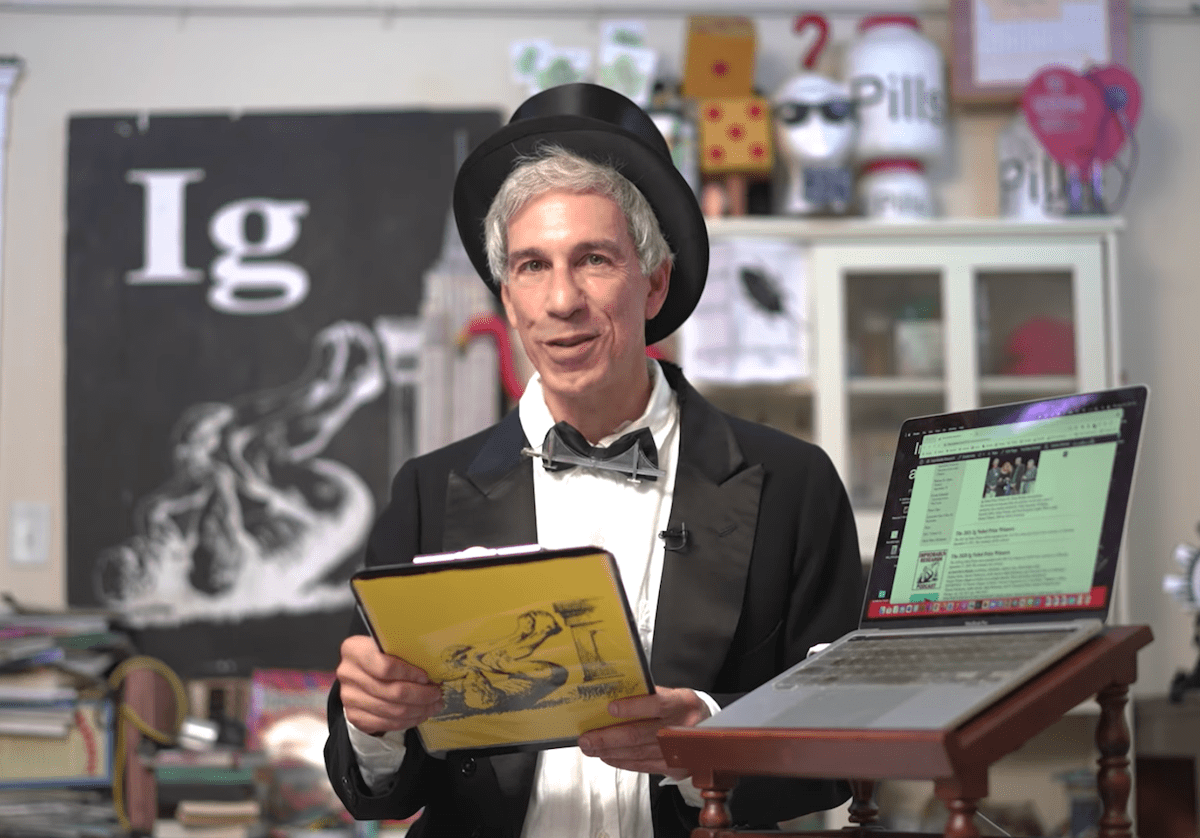

Marc Abrahams is the editor and co-founder of Annals of Improbable Research and the founder and master of ceremonies for the Ig Nobel Prize Ceremony in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. We know things are still difficult. Maybe you’re still wary of gathering together for the holidays the way you once did. And the Ig Nobel Prize ceremony is no exception. This is the award ceremony 31st first annual year. But for the second straight year, it’s been held online not in the storied halls of Harvard Sanders Theater.

But the tradition lives on, and so does our holiday tradition of post-Thanksgiving highlights from the ceremony. Here to help me navigate the awards is Marc Abrahams, Editor of the Annals of Improbable Research. And he’s the ringleader of the awards ceremony, the whole shebang. Welcome back, Marc.

MARC ABRAHAMS: Hi, Ira. It’s good to hear you again.

IRA FLATOW: You too. Congrats on 31 years. We’re celebrating our 30th, so we’ve been right along with you.

MARC ABRAHAMS: Yeah, congratulations to you. Let’s keep going, both of us.

IRA FLATOW: How have things changed over the decades? Any noticeable change?

MARC ABRAHAMS: Oh, my, how much time you got?

[LAUGHTER]

Yeah, I’ll mention a few things. One is the general way that the Ig Nobel Prize has been received. There was at that time, a really widespread fear, especially in the science community, of people who would attack scientists and attack science. And a lot of that fear in the United States was driven by something called the Golden Fleece Award. It was done by Senator Proxmire. So the thing that he would–

IRA FLATOW: I remember, that, yeah.

MARC ABRAHAMS: Yeah, he would announce a list of government-funded things that seemed foolish, that seemed silly, seemed wasteful. And some of those things really were foolish and wasteful, but some of them weren’t. Some of them were simply things that had titles that were extremely unfamiliar to people. And a lot of science, of course, is like that.

So every year, scientists cringed when Senator Proxmire got up and did that, for pretty good reason. When we started the Ig Nobel Prizes, a lot of times, when we talked to an American scientist, the first question out of their mouth was, is this like the Golden Fleece Awards? And we had to explain no.

That was part of the reason at the beginning at the very first year that I invited a bunch of very famous scientists who had Nobel prizes to be part of it. Part of the reason was we just thought it’d be fun and kind of absurd. The fact that we have always had famous scientists as part of it has been very helpful in that way, though, as a sign to everybody that, hey, these people would not be part of it if we were out to do damage.

IRA FLATOW: And a lot of this ceremony this year was essentially a big video call with those real Nobel laureates interacting with the Ig Nobel winners, right?

MARC ABRAHAMS: Oh, it was a big constellation of calls. We had to do a lot of logistics to make this thing work. We keep the prizes top secret until Ig Nobel Day, until the whole thing is webcast. And in order to keep things secret, of course, you need everybody involved to keep things secret.

The winners are spread around the world. And the Nobel laureates who are handing out the prizes are spread all over the place too. So we had a whole series of secret Zoom calls, some of them involving people on five or six different continents, and got all that stuff juggled together. And then in the end, mash it together, add some sugar, or the equivalent, and hey, we’ve got an Ig Nobel Prize ceremony.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. And you do it so well every year. And speaking of every year, what’s the actual award this year?

MARC ABRAHAMS: Like last year, we had the problem to overcome the– the heart of the ceremony, the magic moments are the 10 times when we announce a prize, and a Nobel Prize winner shakes the hand of the Ig Nobel Prize winner and physically hands them an Ig Nobel Prize. Well, the handshake was out because 10,000 miles is a long way to do that. But what we did last year and again this year was make a prize with a very special kind of design.

SPEAKER 1: Now, ladies and gentlemen, now I will show you the coveted Ig Nobel Prize. This year’s prize is a PDF. It’s a document that can be emailed and printed and then assembled to make a gear with human teeth.

MARC ABRAHAMS: Wow. A real gear?

SPEAKER 1: Yes, a real gear made of paper.

MARC ABRAHAMS: With real human teeth?

IRA FLATOW: Uh, well, no, it’s just pictures of human teeth printed on the paper.

MARC ABRAHAMS: And then when we had each presentation, I would announce the prize. And the Nobel laureate would say whatever they want to say, pick up the prize, hold it in front of the camera, and then shove it off to the side of the frame outside the video frame. And then you could see across the world the winner, or sometimes six or eight winners if it was a team, would reach out the side of their video frame and pull in the Ig Nobel Prize.

IRA FLATOW: That’s cool. I like that.

MARC ABRAHAMS: That’s kind of nice.

IRA FLATOW: Maybe an NFT is in your future for these documents.

MARC ABRAHAMS: Oh, my, just raised such a confusing idea. (LAUGHING) Let me think about it, though.

IRA FLATOW: I’ll let you think about it for a while. Maybe next year. OK. Let’s get into some of the awards. Everyone on the internet loves cats. So it’s fitting that you have a prize linked to cat communication, the Biology Prize. Tell us about that.

MARC ABRAHAMS: Yeah, it’s three scientists at Lund University in Sweden. They won this year’s Ig Nobel Biology Prize for analyzing variations in purring, chirping, chattering, trilling, twiddling, murmuring, meowing, moaning, squeaking, hissing, yowling, howling, growling, and other modes of cat-human communication.

SUSANNE SHOTZ: Thank you. I’m so honored to receive this price. As you may know, domestic cats have a large vocal repertoire. And they also vary their voices and their melodic patterns when they communicate using sounds. I became really interested in this variation. And I used the methods that I normally use to study human speech sounds– phonetic analysis– to describe the different catcall types and the variation within each type.

However, I couldn’t have done this without the help of my colleagues in my research project, Joost van de Weijer and Robert Eklund. All the wonderful people working in the Lund University Humanities Lab. And of course, I could never have done this without the help of these guys.

[MEOWING]

[YOWLING]

[HISSING]

[CHIRPING]

[PURRING]

So again, thank you so much.

MARC ABRAHAMS: During the ceremony, Susanne Schotz, who is the main researcher in this, demonstrated each of those means of communication, which was quite entrancing. And then we asked her if she could turn those instantly into a piece of music. We have musicians who are involved in the ceremony. And we had a trombonist, Julia Luneta, who was doing a little trombone fanfare when we presented the prize. So Julia Luneta on trombone and Professor Susanne Schotz acting as a cat did this first-time ever performance of a quick survey of all of the communication sounds that cats and humans use when they speak together.

[TROMBONE PLAYS]

[CAT CHIRPS]

[TROMBONE PLAYS]

[CAT CHIRPS]

[CAT YOWLS]

[TROMBONE PLAYS]

[CAT MEOWS]

[TROMBONE PLAYS]

SUSANNE SHOTZ: [TRILLS]

IRA FLATOW: In this show, we love the microbiome. And I understand this year the Ecology Prize is tied into that. Let’s hear about the Ecology Prize.

MARC ABRAHAMS: Ecology Prize went to a team in Spain who used genetic analysis to identify the different species of bacteria that live in wads of discarded chewing gum stuck onto pavements in various countries.

IRA FLATOW: They actually picked up the gum off the street and analyzed the microbiome?

MARC ABRAHAMS: Oh, they went further than that. They put the gum down. And then they picked it up again much, much later and analyzed over time what the population of bacteria looked like and how that population changed over time in each of those little wads of discarded chewing gum,

During the ceremony, Frances Arnold was the Nobel laureate who presented the prize to them. And as she was presenting it, she was herself chewing a big mother wad of chewing gum.

IRA FLATOW: Only fitting.

MARC ABRAHAMS: The winners also were, too.

FRANCES ARNOLD: I want to thank you– [BLOWS BUBBLE] for this very important contribution to mankind and to our deep knowledge of our built environment.

SPEAKER 1: Thank you.

SPEAKER 2: Thank you very much.

SPEAKER 1: Thank you.

SPEAKER 2: Thank you.

MARC ABRAHAMS: The team will now present its acceptance speech, which was pre-recorded.

[GUITAR PLAYS]

SPEAKER 2: (SINGING TO THE TUNE OF “ALL YOU NEED IS LOVE”) All the chewing gum.

All, the chewing gum. All, the chewing gum. All the chewing gum. All the chewing gum, gum, gum is on the street.

IRA FLATOW: How can you top that? Sometimes I understand that the prizes can be a bit political, like this year’s Economics Prize, obesity of a country’s politicians may be a good indicator of that country’s corruption.

SPEAKER 3: It’s great fun receiving this award. Let me just steal 55 seconds of your attention to tell you what this award is all about. So I downloaded pictures of politicians from internet. And I ran them through an artificial neural network.

This neural network was trained not only to recognize human faces, but also to estimate body mass index. I found that countries that are perceived as relatively corrupt have relatively high estimated body mass index of a median cabinet minister. Whereas countries that are perceived as less corrupt have slimmer politicians. In the follow-up work, I also found that there is intertemporal correlation between obesity of politicians and perceived corruption. So grand political corruption is literally visible from the faces of politicians.

IRA FLATOW: Lots of times on this show, we tell our listeners, don’t try this at home. But your next prize, the Medicine Prize, does not need that warning, I don’t think.

MARC ABRAHAMS: Well, it depends on who’s in your home at the time you’re doing this, I suppose.

[LAUGHTER]

The Medicine Prize went to a team based in Germany who demonstrated that sexual orgasms can be as effective as decongestant medicines at improving nasal breathing.

MARC ABRAHAMS: The prize will be presented by Nobel laureate Robert Lefkowitz.

ROBERT LEFKOWITCZ: Well, I’d like to offer my heartfelt congratulations to this outstanding team for this groundbreaking piece of work. I know how hard you’ve all worked on this project, and certainly this award is a fitting climax for all the work that you’ve done. As the famous soliloquy by Hamlet– I would quote those words– “a consummation devoutly to be wished.” So again, my hardiest congratulations as I present this Ig Nobel Prize to your team.

SPEAKER 4: On behalf of my entire team, I would like to thank you for this prize. We are very honored. Instead of preparing a long acceptance speech, we actually made a little video to explain our research and findings in a fun way. We hope you enjoy it Thank you again.

[VIDEO PLAYBACK]

– This is Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, and one of his best buddies, Wilhelm Fliess, a German physician. In 1897, they theorized on a connection between the nose and genitals, postulating genital spots located inside the nose. Fliess even performed surgery on Freud to prove this link.

– Ow! Ow!

– In the centuries since, the theory has been all but forgotten. In 2020, these guys, Chem and Ralph, picked up the idea. They found out that sexual intercourse with orgasm can improve nasal breathing to the same degree as the congestive nasal spray. So if you or your partner suffer from a block nose, there might be a natural solution with positive side effects. Give it a try. You’re Welcome.

[END PLAYBACK]

IRA FLATOW: Wow. Trying to think of the idea when that first came up to test that out.

MARC ABRAHAMS: Yeah. And also about the discussions that probably had to happen between the various people who were invited to become part of that research effort.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. Tough to top that prize. But let’s try with the always popular Peace Prize. Tell us about the Peace Prize.

MARC ABRAHAMS: When we awarded the Peace Prize this year, the winners didn’t realize which prize they were getting until that moment. And they were shocked and delighted. They thought maybe they were going to get the Biology Prize, or maybe they were going to get another prize.

But we thought this is a fitting Peace Prize. It’s a team in the United States who tested the hypothesis they came up with, the guess they came up with, that humans evolved beards to protect themselves from punches to the face.

MARC ABRAHAMS: The prize will be presented by Nobel laureate Eric Maskin.

ERIC MASKIN: This is it. You richly deserve it. And let me give it to you.

SPEAKER 5: We’re pleased. We’re honored to receive the Ig Nobel Peace Prize. Our question came from the observations that humans are unique among the great apes in having facial hair in males but not in females and that male beards cover some parts of the face that are most vulnerable when one is punched.

SPEAKER 6: We ultimately decided against testing our hypothesis by punching each other, both with and without beards. Instead we used a sheep fleece model to model the hair and an epoxy composite sheet to model the facial bones. We then used a device that drops a known weight, test the samples, and measure the energy required to fracture them both with and without a fleece coating.

SPEAKER 5: We found the total energy absorbed by the samples was 37% greater when the sample was covered with the fleece. This result is consistent with the hypothesis that humans are anatomically specialized for fighting with this There is no doubt that humans are the most empathetic and cooperative species on the planet. But given that reducing violence in the future is a goal that we all share, it is important to keep in mind that our anatomy reminds us that in certain circumstances, we can and sometimes do respond with aggression.

ERIC MASKIN: How want the world did you come to this research topic?

SPEAKER 6: So this– actually, this work came out of an argument I had with a colleague a decade or so ago. We were arguing about sperm whales at a meeting in the hall. And the conversation sort of got out of hand. And at one point, he waved his fist in my face, and he said, I can hit you with this, but that’s not why it evolved.

And while he was doing that, I was thinking, well, wait, maybe there is something to that. I didn’t say anything to him because he was so upset. But we looked at the role that this posture may play in hand anatomy. Then from there, we went to the face. And the face led us to beards.

ERIC MASKIN: Well, that’s science for you.

[LAUGHTER]

IRA FLATOW: I think that’s a worthy follow up to the Medicine Prize, I think.

[LAUGHTER]

MARC ABRAHAMS: I’m sitting here now thinking about what somebody– if they’re taking all of your suggestions and planning to do them in one day, what that person’s day would be like.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. And would they have another day? Each year you have a musical salute. Here’s just a taste of this year’s mini opera about engineering a bridge.

SINGERS: (SINGING) Bridge, bridge, bridge, bridge.

What kind of bridge is the very best bridge a super-duper bridge, the best, best bridge? What [INAUDIBLE] best kind of bridge, the best kind of bridge is the best, best bridge. Which kind of bridge is plenty [INAUDIBLE] whether the weather’s warm or freezing? [INAUDIBLE] suspension. It’s a big suspension bridge.

Bridge, bridge, bridge, bridge.

IRA FLATOW: We need to take a break. And we’ll be back with more from this year’s virtual 31st first annual Ig Nobel Prizes. Stay with us. This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios.

This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. In case you’re just joining us, we’re talking with Marc Abrahams, Editor the Annals of Improbable Research and master of ceremonies for the Ig Nobel Prize ceremony now in its 31st first annual year. Tell me how people get selected for this high honor, the Ig Nobel Prize.

MARC ABRAHAMS: Anybody can send in a nomination. And anybody can nominate themselves. And lots of people do. In a typical year, we get something like 10,000 new nominations.

We also consider things from the past. And the Ig Nobel Board of Governors, a large group, which is spread around the world, looks at those things. And every year we choose 10.

The criterion is always the same. The criterion is fairly simple. It’s everything that wins a prize has done something that makes people laugh and then think. There should be something about it that can be described really concisely. And when anybody, anywhere, from any background hears that their first reaction should be to laugh. There should also be something about this achievement that sticks in people’s minds so that after they laugh, even a week or so later, they’re still thinking about it. And they want to tell their friends about it and argue about it.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s move on to a price for something I would have never guessed was a real problem, the Entomology Prize for a new method of cockroach control on submarines. Tell us about it.

MARC ABRAHAMS: Yeah, well, that was the title of a research paper that they published back in 1971, “A New Method of Cockroach Control on Submarines.” Let me ask you to consider something. A few years ago, there was a movie called Snakes on a Plane. Now, I think it’s not too difficult to imagine somebody making a movie called Cockroaches on a Submarine.

The Entomology Prize is awarded to John Mulrennan, Jr., Roger Grothaus, Charles Hammond, and Jay Lamdin for their research study, “A New Method of Cockroach Control on Submarines.” The prize will be presented by Nobel laureate Frances Arnold.

FRANCES ARNOLD: I’m thrilled to be able to award you this prize for your contributions to an age-old battle of man versus cockroach, a battle we have not yet won. But your contributions were important.

SPEAKER 7: Thank you. I’ve been out of the Navy for– I retired in 1979 from the Navy. So it’s been a long time. Back in those days, we were limited on what we could do. The procedure that had been used for years was to fumigate the submarines with carboxide gas. Now, carboxide gas is a combination of carbon dioxide and ethylene oxide.

And the reason we had to do what we did was because up in New London, we had an incident where a submarine was fumigated with caroboxide in the wintertime. And after they aerated the submarine and the crew went back aboard, the ethylene oxide had condensed into a liquid form. And when they heated the submarine back up, the ethylene oxide went back into gaseous state, and we had an incident where one of the crew members was affected by the gas.

And that was one of the problems they had. And in fact, there was a fatality in one of those incidents. So we had to find some other way to do it that was safer. And that’s what we did.

It was safer. It was more economical. And it was just as effective or more effective than the gas. So it worked out. That was our mission. And I think we accomplished our mission. And the Navy was happy at the time. I don’t know what they’re doing now, to be honest with you.

IRA FLATOW: That was really cool. Our next prize is–

MARC ABRAHAMS: Chemistry Prize.

[ACCORDION PLAYING]

The winners represent these countries– Germany, the UK, New Zealand, Greece, Cyprus, and Austria. The Chemistry Prize is awarded to Jorg Wicker Nicolas Krauter, Bettina Derstroff, Christof Stonner Efstratios Bourtsoukidis, Achim Edtbauer, Jochen Wulf, Thomas Klupfel, Stefan Kramer, and Jonathan Williams for chemically analyzing the air inside movie theaters to test whether the odors produced by an audience reliably indicate the levels of violence, sex, antisocial behavior, drug use, and bad language in the movie the audience is watching. The prize will be presented by Nobel laureate Barry Sharpless

BARRY SHARPLESS: Research on smell is under valued. And it’s very important. It either makes us dreadfully fearful or disgusted, or we’re happy there’s food down the road. And that was true for little guys, this bacteria. And so I think I really look forward to meeting you. I hope I can get to Germany or you get over here in San Diego. And I’d love to talk to you about things.

MARC ABRAHAMS: And now the prize?

BARRY SHARPLESS: Oh the prize.

MARC ABRAHAMS: Yeah, the prize.

BARRY SHARPLESS: OK. This is the prize.

MARC ABRAHAMS: And now the winners will present their acceptance speech by pre-recorded video.

SPEAKER 8: The instruments that you can see and hear behind me are normally used to investigate the chemistry going on over the Amazon rainforest. But for this project, we took these instruments to a local movie theater.

And here in the movie theater, if you measure the air composition continuously, you’ll see that some chemicals vary in sync with scenes in the film. And what that means is that the audience is broadcasting out chemicals as they respond emotionally to the contents.

IRA FLATOW: OK. Let’s move on to a pair of prizes for research that certainly impacts me, and pun intended there, first the Physics Prize.

MARC ABRAHAMS: Mm-hmm. And then I want to hear exactly how this impacted you. This was a pair of prizes, different groups not at all working together– although it turned out that they were aware of each other, not aware of each other’s research just aware that each other existed. And it turned out these two prizes really fit together well. The Physics Prize went to a team from the Netherlands, Italy, Taiwan, and the USA who conducted some experiments to learn why pedestrians do not constantly collide with other pedestrians.

The prize will be presented by Nobel laureate Marty Chalfie.

MARTY CHALFIE: It’s a real pleasure to present you with this year’s Ig Nobel Prize in Physics. Congratulations to all of you. I only have one real question, though. Was this study done with or without cell phones?

SPEAKER 9: Well, [INAUDIBLE] where’s the cell phone? He had the cell phone. It depends. There were people with and without cell phone. We have five millions. So I assume, yeah, many, most of them.

MARTY CHALFIE: I just wondered if the people that were looking at their cell phones collided more with other people.

SPEAKER 9: Oh, that’s a very good question. This is something we need to look into. But we don’t have resolution to distinguish people with cell phone, without for the moment– at the moment. So this is something we cannot yet do. But yeah, this is a very good point.

Greetings from the Netherlands, from California, and from Italy. First of all, we wish to thank the committee for the award of this Ig Nobel Prize.

SPEAKER 10: We are flattered that people laughed and then thought because of our work.

SPEAKER 9: So thanks.

SPEAKER 8: Thank you.

SPEAKER 10: Thank you so much.

SPEAKER 9: Now to the matter. Do you still think that physics can only be used to explain how people walk?

SPEAKER 11: Actually, you can use physics to explain the hydrogen atom.

SPEAKER 12: Physics can even be used to describe gases of interacting molecules which resemble human clouds.

SPEAKER 10: We now work– we studied millions of pedestrian trajectories. And we have shown that we can explain it [INAUDIBLE] in a robust way, of course, from a statistical point of view.

SPEAKER 11: Gas molecules in a crowd can also kiss each other or run.

SPEAKER 10: Remember, even if you think you can choose your destination–

SPEAKER 12: –regardless whether a person in a crowd–

SPEAKER 11: –or a gas molecule–

SPEAKER 10: –physics can predict your statistics.

MARC ABRAHAMS: Do you have any questions that you would like to ask Marty Chalfie?

SPEAKER 9: How do we get the Nobel Prize ourselves?

MARTY CHALFIE: I think this is a very good start. Work on something no one else has ever worked on.

IRA FLATOW: You asked me why I talked about this impacting me. Because here in New York, the streets are so congested all the time that you really have to weave your way through the pedestrians not to hit any other pedestrian.

MARC ABRAHAMS: And therefore, sort of, the Ig Nobel Prize for Kinetics went to a team in Japan, Switzerland, and Italy for conducting some experiments to learn why pedestrians do sometimes collide with other pedestrians. Part of their experiment was what I think you’re probably hinting at, which was they’re looking at what happens when some of the pedestrians are looking at cell phones in their hand while they’re walking. And what they found was, hey, guess what? They’re a little more liable to collide with other people.

SPEAKER 14: We are super happy to accept the Ig Nobel Prize. We discovered mutual [INAUDIBLE] between pedestrians facilitates the order [INAUDIBLE] movement in human crowds.

SPEAKER 15: In our experiment of bi-directional flow, the visual distract only some of the pedestrians to disturb their anticipatory abilities. Then we observed the distraction clearly delayed the collective pattern formation.

SPEAKER 16: Surprisingly, not only distracted pedestrians, but also nondistracted ones had trouble avoiding collisions in advance while navigating. So we can see that anticipation is mutual.

SPEAKER 17: To distract pedestrians, we got participants to use this.

SPEAKER 14: And this mobile device while walking. However, we hope you are not just distracted by the list of mobile use but in the [INAUDIBLE] interaction ability where mobiles are not used. We [INAUDIBLE] mutual [INAUDIBLE] is important to understand the barriers to organizing systems.

MARC ABRAHAMS: They also discovered something they said that I find pretty interesting, that when people are walking on crowded sidewalks, everybody is doing a lot more watching and on some level, calculating then they realize. Everybody is paying a lot more attention than they probably realize to what everybody else is doing, about is there a collision imminent.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. Do you have a favorite award this year, your own personal favorite?

MARC ABRAHAMS: Oh, boy. That’s always a difficult question. And you know that.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, I know, put you on the spot. You could say the usual, like my children. I can’t pick out any one

MARC ABRAHAMS: OK. Here’s one. And if you asked me yesterday, we would have got a different answer. But the final prize of the ceremony this year was the prize to an international team that did the research that showed them that probably the safest way to transport a rhinoceros over a long distance is to dangle it from a helicopter upside down.

The prize will be presented by Nobel laureate Rich Roberts.

RICHARD ROBERTS: Is the price– and I have to say, when I have to be transported to a safer place, I hope not to be doing it upside down. But many congratulations.

SPEAKER 18: We were asked, Robin, for conservation purposes to move a significant number of rhino from a core breeding area to other very remote regions. Capture and release is going to be in really difficult places to get to. So we looked at the options and decided that moving the rhinos under a helicopter would probably be the safest, most effective, and animal friendly way of doing it. Pete?

SPEAKER 19: So we came up with a plan of lifting them up by their feet, having them upside down. We then lifted a rhino with a crane. It managed that OK. And we were good to go, good to lift a rhino with a helicopter.

SPEAKER 20: The thing I love about wildlife veterinarians is you guys have to really think on your feet and think outside the box. And I think hanging rhinos upside down is a good example. You have to be ingenious and creative and sometimes even a little bit crazy to move rhinos this way.

MARC ABRAHAMS: Rich, you’ve had a glimpse at what all of these people did to win their prize.

RICHARD ROBERTS: Yeah. I felt sorry for the rhinoceros, I must say.

MARC ABRAHAMS: Well, should he feel sorry for the rhinoceros?

SPEAKER 20: No.

MARC ABRAHAMS: Why?

SPEAKER 20: Because they’re being moved to a safe area where they’re protected.

RICHARD ROBERTS: That I know. It was just the manner of transportation that I was concerned about.

SPEAKER 20: Well, that’s why we did our research.

[LAUGHTER]

SPEAKER 19: The rhinos in the experiments were only two inches off the ground.

SPEAKER 20: Maybe six inches, Dr. Gleed.

MARC ABRAHAMS: Did you run any tests, before you had a large rhinoceros, using any of yourselves?

SPEAKER 19: Actually, we first tested a lot of other animals before we got to the rhino and, of course, including a few human beings. So, yeah, we didn’t start with rhino, that’s for sure.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. Wow! Marc, do you think now that you’re in 31 years, did you ever expect that it would be as long lasting as it has been?

MARC ABRAHAMS: Expect? No. Hope? Yeah. When you start something, of course, you always hope it’s going to have a long lifetime. And you hope it’s longer than your lifetime. I really never expected the dangling upside-down rhinoceroses.

IRA FLATOW: [LAUGHS] Me neither. I’m hoping for your next year back in Cambridge.

MARC ABRAHAMS: Thanks. That’s itself a big question.

IRA FLATOW: Fly that rhino in for the show.

MARC ABRAHAMS: Oh. Oh, that’s an idea. Who would think of such an idea?

IRA FLATOW: Not me. Do you have any final thoughts you want to deliver, a standard final thought for the winners?

MARC ABRAHAMS: Yeah, two thoughts, in fact. One is if you listening, know of somebody or you run across somebody or even read about somebody who’s done something that you really think deserves an Ig Nobel Prize– it makes you laugh, and it really makes you think, and you think it will happen that same way to other people– let us know about it. That’s how we learn about most of the things that win a prize. One person somewhere heard about it and told us about it. And the final thought, as always, is if you didn’t win an Ig Nobel Prize this year, and especially if you did, better luck next year.

IRA FLATOW: And there you have it, Marc. And congratulations again on 31 years.

MARC ABRAHAMS: Thanks and congratulations to you and everybody at Science Friday on 30 really wonderful years.

IRA FLATOW: Thank you very much. We’ve run out of time. I’d like to thank Marc Abrahams, Editor of The Annals of Improbable Research and ringleader of the Ig Nobel Prize Awards ceremony. Let’s hope for next year back in the theater.

Copyright © 2021 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

As Science Friday’s director and senior producer, Charles Bergquist channels the chaos of a live production studio into something sounding like a radio program. Favorite topics include planetary sciences, chemistry, materials, and shiny things with blinking lights.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.