Hurricane Helene’s Damage Could Affect The Global Tech Industry

11:25 minutes

After making landfall on September 26, Hurricane Helene devastated regions in the southeastern US. Over 200 people are confirmed dead so far. About a million people are still without power, and many lack clean water.

As climate change intensifies, hurricanes like Helene are expected to occur more often and be more intense. What’s become very clear in the last few years is that due to the interconnectedness of the modern world, extreme weather in one place can have global implications.

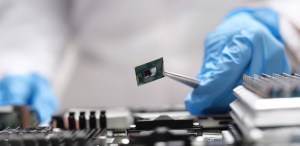

For example, Spruce Pine, North Carolina, home to around 2,200 people, flooded during Hurricane Helene. The town is also home to several mines that produce some of the world’s purest quartz, an ingredient necessary to make solar panels, smartphones, semiconductors, and more.

Ira talks with Umair Irfan, senior correspondent at Vox, about this and other science news of the week, including a completed map of a fruit fly’s brain, how scientists in the United Kingdom are screening newborns for rare diseases, and how octopuses and fish are hunting as a team.

Umair Irfan is a senior correspondent at Vox, based in Washington, D.C.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. A bit later in the hour, Mario Livio talks about the likelihood of finding extraterrestrial life. Plus, how a treatment that uses magnets to stimulate the brain is helping folks combat depression. But first, one week ago, Hurricane Helene devastated regions in the Southeast US. More than 200 people are confirmed dead so far. And about a million people are still left without power, many without clean water. As climate change intensifies, hurricanes like Helene are expected to occur more often and be more intense. And that’s what’s becoming very clear in the last few years.

And what’s becoming very clear in the last few years is that, due to the interconnectedness of the modern world, extreme weather in one place may turn out to have global implications. For example, Spruce Pine, North Carolina, home to around 2,200 people, flooded during Hurricane Helene. And this town is also home to several mines that produce some of the world’s purest quartz, an ingredient necessary to make solar panels, smartphones, semiconductors, and more. Here with this story and other science news of the week is Umair Irfan, senior correspondent at Vox, based in Washington, DC. Welcome back, Umair.

UMAIR IRFAN: Hey, Ira. Thanks for having me.

IRA FLATOW: All right, let’s start right in with this story. What happened to the mines?

UMAIR IRFAN: Well, as you noted, Hurricane Helene has been drenching a big chunk of inland parts of Western North Carolina, including this area around this community of Spruce Pine. And it’s put about 2 feet of water there. And it has stopped the operations of these mines because now they’re soaked. And they’ve been closed indefinitely.

IRA FLATOW: And why are these mines so important to chipmaking?

UMAIR IRFAN: Well, as you noted, they’re big sources of quartz. But what’s special is the quartz they have there is very pure. It has very few impurities. And while mining quartz is expensive, it means that it needs less processing. And so these mines around Spruce Pine account now for about 70% of the global market for high quality quartz. And this quartz material is actually used to make crucibles, which is then used to melt down polysilicon that you then use to make microprocessors, solar panels, and other kinds of electronics. But these crucibles wear out over time. And so you need to be constantly replacing them. And that’s why you need a constant supply of fresh, high quality quartz in order to continue making all the chips that the world needs.

IRA FLATOW: So I’m imagining this is going to have an effect on the price of chips somewhere along the line.

UMAIR IRFAN: Yeah, a lot of analysts are anticipating that this is going to raise the cost of electronics because it’s raising a lot of the processing costs. But it’s also going to force a lot of people in the supply chain to start looking elsewhere. So they may start prospecting for other sources of high quality quartz, or they may invest a lot more in trying to get these mines back up and running.

IRA FLATOW: This reminds me of the unintended consequences or the unknown consequences of climate change, like last year, when the Panama Canal’s water supply was so low because of a drought. And the entire global shipping network was disrupted. And as we noted, as the effects of climate change intensify, we’re going to even see, right, more of these localized disasters having global implications.

UMAIR IRFAN: Right. Our economy is so interconnected. And we just keep finding out that there’s all these little chokepoints that are built in. We’ve been talking a lot recently about the global semiconductor industry and how so many of them are made in Taiwan and why we need to make sure they’re made in other countries. But now we’re finding even further upstream of those microprocessors, just the raw materials we need to make them, also have their own chokepoints. And so we need to start thinking a lot more carefully about what it is that we need to make all the things that make the world run and then start coming up with backup plans, because we can’t count on them to survive some of these disasters that we’re facing.

IRA FLATOW: All right. Let’s move from minds to minds. Scientists completely mapped the brain of a fly. Umair, tell us about this. Why is this important?

UMAIR IRFAN: For the first time, scientists have been able to actually conduct a super-detailed analysis. And visit the most complex brain that they’ve mapped out so far. So a fly’s brain typically has around 130,000 cells and about 50 million connections. And by cutting a fly’s brain into slices and taking these high-resolution microscopic photographs and then stitching them together with computer programs and AI, scientists were actually able to develop an atlas of how a fly’s mind actually is wired. And from there, they’re hoping that they can actually understand how a lot of these neural processes work.

IRA FLATOW: Interesting. I think it’s safe to say that our brains are a little more complicated, right?

UMAIR IRFAN: A little bit. We’re talking about a hundred billion neurons and a hundred trillion synapses, so a little bit more complex there.

IRA FLATOW: But that doesn’t mean we can’t learn anything.

UMAIR IRFAN: Well, that’s right. And so we use flies as a model organism in a lot of science, in genetics and so forth. But here, we can start seeing how some of the simple processes work, like how it has reflexes and how it makes decisions. And from there, we can perhaps scale that up and understand more complex things, like how thoughts form, how we make decisions, and how we feel emotions and other complex things that go on in our brains.

IRA FLATOW: Right, right. Let’s move on to some cutting edge medicine. I’m talking about a program in England that is starting to screen newborn babies for rare disease. How is that going to work?

UMAIR IRFAN: Babies already often get this heel prick blood test that typically looks for about nine diseases. And the United kingdom’s National Health Service is now going to sequence the genomes of about 100,000 babies completely to try to look for even more diseases. They’re trying to develop a test that can find more than 200 rare genetic disorders. And the idea is that some of these disorders can actually be treated or mitigated early in life if they’re caught early.

IRA FLATOW: Wow, wow. We’re not going to have that in this country anytime soon, I don’t–

UMAIR IRFAN: Well, in the US, we’re always concerned about patient privacy. It’s also cost and getting a lot of people to opt in. And there are also some ethics concerns here as well, because some genetic diseases and genetic markers, for instance, can show the risk of a disease, but it doesn’t necessarily manifest. And sometimes, giving people information about a disease that they have no control over and no treatment for may not necessarily help them. And so there’s a question of how useful this information may be in some circumstances.

IRA FLATOW: Fascinating, fascinating. OK, let’s pivot to outer space, where some NASA spacecraft are feeling their age. Let’s start with the Curiosity rover on Mars. Feeling a little old there?

UMAIR IRFAN: Yeah, it’s been there since 2012. It’s covered more than 20 miles, which is a fairly long distance by Martian standards. And NASA, this week, was taking some photos of the spacecraft itself to do a status check. And they posted these photos of its aluminum wheels and found that there’s some big gaping holes in the tread there, showing that the terrain there is quite rough and quite hard on the vehicle.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. So what does that mean for the spacecraft?

UMAIR IRFAN: Well, it means that it has to be a lot more careful for how it gets around. It uses these aluminum wheels. And it weighs about 2,000 pounds, because conventional tires don’t work in such a low pressure environment. And so NASA engineers are trying to do some wayfinding and planning to avoid some of the more nasty terrain. They can actually make the spacecraft reverse over certain regions to try to minimize damage. But this is just kind of the phenomenon that they’re just going to have to deal with as these craft continue to age.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, well, speaking of age, let’s talk now about the Voyager 2, which is billions of miles away. And it seems it’s running out of power, finally?

UMAIR IRFAN: Right. So it’s using this plutonium-powered reactor that decays at about 4 watts of power each year as its nuclear fuel burns up. And so, over the years, scientists have been trying to manage that diminishing power supply. And then recently, they said that they’re going to be switching off the Plasma Science Instrument. This is a device that they use to measure the amount and direction of plasma. And this is how the probe situates itself in the solar system and finds out whether it’s still within the sphere of the sun’s influence or into interstellar space.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, this is one of NASA’s most beloved probes, isn’t it?

UMAIR IRFAN: Yeah, as you mentioned, it’s 12.8 billion miles from Earth. It’s the furthest away a human-made object has ever gotten. And scientists say that there is still enough juice in there to keep it running until the 2030s. So it’ll be interesting to see just how much more information and how much more life they can squeeze out of this spacecraft that’s almost 50 years old.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s wrap up this roundup with some funny sea creatures, starting with dolphins. They always look like they have a natural smile on their face. But it may turn out that they actually know how to smile, right?

UMAIR IRFAN: Right. So researchers who were observing dolphins in captivity, they were filming them. And they noticed that, while dolphins do have that sort of upturned grin, they actually do this open-mouth behavior that scientists say actually does convey the emotion of happiness, because they see them engage in this when they’re playing with other dolphins or when they’re doing play-fighting and when they’re interacting with other dolphins and with human caretakers. And they’ve also seen other dolphins reciprocate that. So it seems like this is a form of facial communication among the dolphins to indicate that they’re engaging with each other, but not in a hostile way.

IRA FLATOW: Huh. How did they figure this out?

UMAIR IRFAN: Well, they were filming them over a long period of time in these different aquatic parks in Europe. And they saw their behavior and looked at 80 hours of footage and saw that dolphins would kind of shove each other there and push each other away but then immediately look at each other and say, basically with their mouths open, as a way to indicate, just kidding, not trying to be hostile, take it easy, just messing around. And so we see a similar behavior in primates. So it’s kind of interesting to see this also happening in dolphins, too.

IRA FLATOW: Now, I understand that cameras also caught octopuses doing some funny behavior.

UMAIR IRFAN: Divers studying the octopuses in the Red Sea captured about 13 instances of octopuses recruiting fish to help them hunt. They basically worked with different species of fish to forage for other smaller fish or for mollusks. And the octopuses were actually kind of serving as commanders, sort of as generals here, sending their troops out to look for prey to hunt.

IRA FLATOW: So the octopus is sort of keeping this little army of fish in line?

UMAIR IRFAN: Yeah, exactly. So as the octopus advances on the seafloor, the fish would advance with it. They would forage in an area. They would pause for a while. And then, when the octopus moves again, they would move with it. And interestingly enough, the octopus could also recognize which fish were actually doing their part and which fish were freeloaders, the ones that were just sort of scavenging and not really helping out. And it would react to those fish by actually kind of punching it with their tentacles, so trying to keep everybody in line and working.

IRA FLATOW: Never ceases to amaze me just how smart those octopuses really are. Thank you, Umair.

UMAIR IRFAN: My pleasure. Thanks for having me, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: Umair Irfan is a senior correspondent at Vox, based in Washington, DC.

Copyright © 2024 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Rasha Aridi is a producer for Science Friday and the inaugural Outrider/Burroughs Wellcome Fund Fellow. She loves stories about weird critters, science adventures, and the intersection of science and history.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.