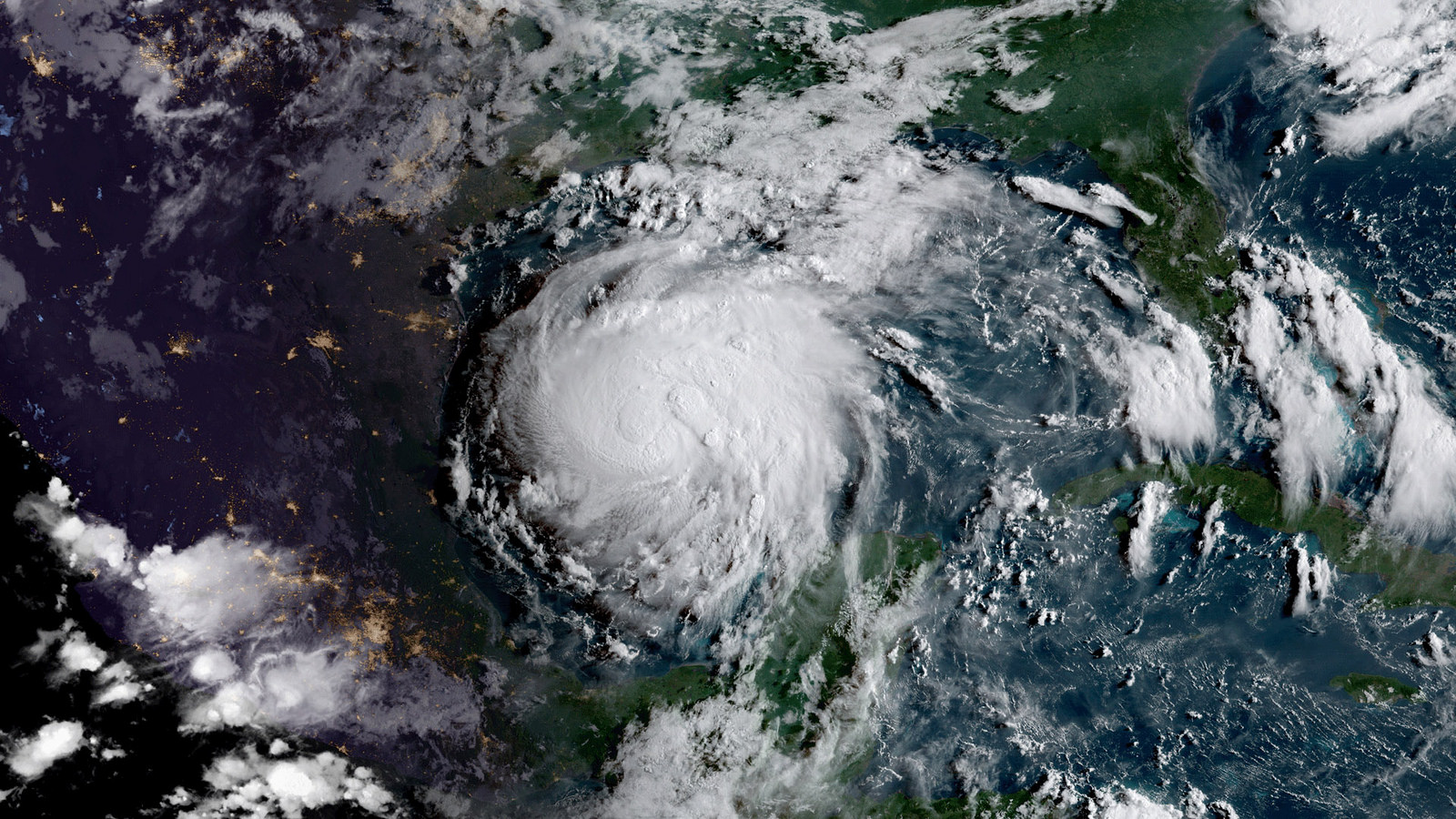

Hurricane Harvey And The New Normal

33:33 minutes

This segment is part of our special coverage of Hurricane Harvey. Learn how Harvey could be a disaster for public health, and how developers are building with climate change in mind.

“There’s never an ideal time to talk about how climate change is magnifying some of these natural disasters,” says Michael Mann, distinguished professor in the department of meteorology and geosciences at Pennsylvania State University. “But it is important to talk about it.”

As Harvey battered Houston last weekend and floods inundated Southeast Asia in the days following, many did indeed begin to talk about climate change. Mann and other climate scientists say that climate change has intensified these storms so much that we need a new set of guideposts. Predictions we could’ve made in the past are no longer accurate, and the rules that used to help us plan for events like Harvey no longer apply. We’re left with overwhelmed infrastructure and building codes that don’t take into account new conditions.

[Need to talk about climate change with a denier? Try these tips.]

“When we use the past as our guide, it doesn’t serve us well for dealing with the greatly amplified levels of risk that we now face,” Mann said. He joins Ira to discuss this “new normal” from climate change, and lays out a two-fold approach for how to live in and with it.

There’s very little doubt among scientists that climate change has ratcheted up the potential intensity of hurricanes and other large storms, Mann says. “There’s now a pretty solid consensus that … the strongest storms will be stronger.”

The contrast between warm temperatures at the surface of the ocean and cold temperatures at different layers in the atmosphere determine the intensity of hurricanes, he says.

[How do we gauge the impact of climate change on hurricanes?]

To understand how that happens, we can think of hurricanes as “heat engines.” At the start of a hurricane, warm air near the surface of the ocean rises, leaving a pocket of lower pressure air below. Other air from surrounding areas fills that pocket, and in turn warms and rises. As this cycle continues, “new” air swirls as it replaces the air that rises from the pocket. Meanwhile, the warm, moist air in the sky then forms a system of clouds, which spins and grows like an engine feeding off heat.

The contrast in surface and aloft temperatures drives that engine, and, thanks to global warming, surface temperatures are rising significantly. “It’s making those heat engines more efficient,” says Mann. And with more efficient heat engines come more intense storms.

While these higher-intensity storms may be considered part of the “new normal” of climate change, Mann says it’s not so simple.

“The ‘new normal’ sort of implies that things have settled into a new state, and you just have to figure out how to sort of deal with that new state,” he says. “But with climate change, it’s an ever-shifting baseline. It’s not stopping here.”

Harvey, for example, created what has been referred to as a “500-year flood.” But, according to local papers, Harvey is the third 500-year event to have hit the Houston area in the past three years. How can that be?

“With climate change, it’s an ever-shifting baseline. It’s not stopping here.”

That number isn’t a time frame — it refers to the chance that a storm will occur at all. When we talk about a 500-year event, that means that it’s so rare and unusual that, based on chance alone, we estimate that there is a 1 in 500 chance of it occurring in any given year.

But those estimates are based on historical data.

“The old rules don’t apply anymore,” said Mann. “We’re no longer talking about chance alone. We’ve loaded the dice. We’ve loaded the weather dice by warming the planet and intensifying these storms and raising sea levels to the point where a storm that we’ve called a 1000-year event … is now a storm that we expect to happen once in maybe 20 or 30 years.”

“The old rules don’t apply anymore. We’re no longer talking about chance alone. We’ve loaded the dice.”

And that data may continue to change. If we continue down the road we’re on and make no adjustments to climate change, Mann says, then these sorts of events could eventually become two-year or three-year events.

“In other words,” he said, “we get a Harvey-like event impacting the Gulf Coast, or a Sandy-like event impacting the New Jersey and New York City coast once every few years … Imagine having to deal with something like that every few years.”

At that point, Mann says, “we’re talking about the retreat from our coast lines. We’re talking about literally giving up on the major coastal cities of the world and moving inland.”

So, what do we do? Mann suggests a two-pronged approach.

One aspect is implementing adaptive measures that take into account the climate change that is already here.

“There’s still a certain amount of additional warming and sea level rise that’s already baked in,” Mann says. “We can’t stop it. It’s a consequence of the greenhouse gases we’ve already put into the atmosphere that will continue to warm the planet and raise sea levels for some time.”

We’ll need to build better and taller seawalls, engineer more resilient infrastructure, and, eventually, slowly retreat from our coastlines, he says.

[The Dutch know a thing or two about water management, and they’ve got a new plan.]

“That having been said,” he continues, “it’s equally important from a mitigation standpoint to try to do something about the problem at its source.”

What does that mean? Reducing carbon emissions and moving away from fossil fuels and toward renewable energy sources.

“We’re going to continue, in principle, to see worse and worse events of this sort,” says Mann. “Stronger storms producing even greater amounts of rainfall if we continue to warm the planet and warm the oceans. So, needless to say, the only thing that’s going to stop that cycle is acting on climate change and moving away from fossil fuels and towards renewable energy.”

[Some say switching to entirely renewable energy by 2050 may not be as tough as we think.]

Michael Mann joins Ira to further discuss how we can continue to adapt to that “ever-shifting baseline.” In addition, Rachel Noble, professor at the Institute of Marine Sciences at University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, discusses the chemical and biological factors that come with rising waters, and what sort of bacteria are living in the floodwaters. Finally, Simon Koster, a principal at JDS Development Group, looks ahead to resilient design, and one building in particular in Manhattan that already has been constructed with these adaptations in mind.

Neena Satija is an investigative reporter and radio producer for the Texas Tribune and Reveal Podcast, based in Austin, Texas.

Dr. Michael Mann is the author of Our Fragile Moment: How Lessons from Earth’s Past Can Help Us Survive the Climate Crisis, a professor of Earth & Environmental Science, and the Director of the Penn Center for Science, Sustainability and the Media at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, PA.

Simon Koster is Principal at the JDS Development Group in New York, New York.

Rachel Noble is a distinguished professor at the Institute of Marine Sciences at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill in Morehead City, North Carolina.

Katie Feather is a former SciFri producer and the proud mother of two cats, Charleigh and Sadie.

Johanna Mayer is a podcast producer and hosted Science Diction from Science Friday. When she’s not working, she’s probably baking a fruit pie. Cherry’s her specialty, but she whips up a mean rhubarb streusel as well.