Why Oxen Were The Original Robots

17:00 minutes

In media and pop culture narratives about robotic futures, two main themes dominate: there are depictions of violent robot uprisings, like the Terminator. And then there are those that circle around the less deadly, more commonplace, fear that machines will simply replace humans in every role we excel at.

There is already precedent for robots moving into heavy lifting jobs like manufacturing, dangerous ones like exploring outer space, and the most boring of administrative tasks, like computing. But roboticist Kate Darling would like to suggest a new narrative for imagining a better future—instead of fighting or competing, why can’t we be partners?

The precedent for that, too, is already here—in our relationships with animals. As Darling writes in The New Breed: What Our History With Animals Reveals About Our Future With Robots, robotic intelligence is so different from ours, and their skills so specialized, that we should envision them as complements to our own abilities. In the same way, she says, a horse helps us travel faster, pigeons once delivered mail, and dogs have become our emotional companions.

Darling speaks with Ira about the historical lessons of our relationships with animals, and how they could inform our legal, ethical, and even emotional choices about robots and AI.

Kate Darling is author of The New Breed: What Our History With Animals Reveals About Our Future With Robots (Henry Holt, 2021) and a research specialist in the MIT Media Lab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

JOHN DANKOSKY: This is Science Friday. I’m John Dankosky in for Ira Flatow. As you may have heard, the robots are coming. But what could coexisting with them truly look like? In this conversation, Ira and roboticist Kate Darling offer a vision inspired by our age old relationship with dogs, oxen, and other animal partners.

IRA FLATOW: There are two stories you see a lot about robots. The first is the robot uprising, right? You’re probably thinking about Arnold Schwarzenegger in Terminator or I, Robot. The second is robots will replace us story. You recall that movie AI. That story is much more present in the news, this fear that we’ll soon have robots and AIs that can and will put people out of work.

My next guest doesn’t believe either of those stories is inevitable. And she wants us to look at a different story, one that has already happened. And I’m talking about our history with animals as co-workers as a guide to the future with robotics. Kate Darling is a research specialist at MIT’s Media Lab, author of The New Breed– What Our History with Animals Reveals about Our Future with Robots. Welcome to Science Friday.

KATE DARLING: Thanks for having me.

IRA FLATOW: Well, what does our history with animals reveal about our future with robots?

KATE DARLING: You know, it’s always struck me in all of the conversations that we have about robots that we’re subconsciously comparing them to humans. We compare artificial intelligence to human intelligence. We compare robots to people. And that’s what leads to these science fictional notions of robot uprisings or robots replacing us.

But it just seems like that’s the wrong analogy because artificial intelligence is not like human intelligence at all. So if we look at our history of working with a very different type of intelligence, animals, and we look at how we’ve domesticated animals and partnered with them throughout history, that seems like a much better way to think about these technologies moving forward.

IRA FLATOW: I remember in college studying BF Skinner using pigeons to guide missiles. You mentioned pigeons as the original drones here.

KATE DARLING: That’s right. I mean, we’ve used animals for so many different things. And I love that you mentioned the ultimately canceled project where BF Skinner was using pigeons to guide missiles. So you could say it was the first autonomous missile system before we had machines that could do this for us. And we’ve used the autonomy of animals and the intelligence and the sensing ability of animals for millennia to help us do these things.

And there’s so many fun parallels to how we’re using robots today and what is ultimately the best use case for robots which is supplementing human ability, doing things that we’re not able to do on our own, not that I’m particularly a fan of self-guided missile systems and some of the ways that they’re being used, but it’s just an interesting example of how these things aren’t new. We have partnered with these non-humans that can sense and think and make autonomous decisions and learn for such a long time, why aren’t we thinking about that as the analogy when we talk about robots?

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, because we all can recall and there are still some societies that use oxen, for example, to pull carts and do work. Is that where you’re going to using animals as companions for helping us get work done?

KATE DARLING: That’s one of the ways that we can use robots. So like you said, we’ve used oxen in farming. We’ve used horses to let us travel the world in new ways. We’ve used pigeons to deliver mail. But the point isn’t that animals and robots are exactly the same or that they have the same abilities. There are a lot of differences between animals and robots. You can’t dictate an email to an animal, and a lot of animals are better at staying on their feet, for example, than most robots that tend to fall over.

The point of the book is that this analogy lets us open our minds to new ways of using these technologies that aren’t a replacement for human skill because this idea that we can, will, or should replace people is very limiting. And I don’t think that we should be trying to recreate skills that we already have when we have the opportunity to create something supplemental that can help us pull the plows. That is disruptive in the way the animals have been but not this 1 to 1 replacement that we’re constantly hearing about in the news.

IRA FLATOW: OK, so open my mind up to some of those ways that we can work with robots.

KATE DARLING: Traditionally, in robotics, the most compelling use case has been anything that’s dirty, dull, or dangerous, the three Ds. And we’ve already been pretty successful over the past five decades at using robots in factories or in settings where it’s dangerous for people or not great for people to be doing repetitive or harmful work or going to space. These are really the really good use cases for robots that we’ve already seen.

But beyond that, I mean, robots have so many physical and sensing abilities that we don’t have. I think that we should really, really be thinking outside of the box on how we use these technologies. I mean, we’ve used animals for so many different things. We’ve used them as tools. We’ve also used them as our companions. And I also believe that robots might be useful in a social sense. And in fact, robots might actually be able to offer something in health and education when we use them in this social way as well.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s continue talking about the history we have with animals. Even pets are a relatively new innovation, aren’t they?

KATE DARLING: They are. In Western society, this idea of having a dog that’s a member of the family and is only there as a member of the family and not there to guard the house or perform some function is relatively new. And in the beginning, when we started having more of an emotional connection to animals, there were even some people, some psychologists, who raised some concern about that and said, well, this could be too much. It might take away from people’s ability to form human relationships and friendships if they get too emotionally involved with animals.

And of course, that quickly turned out to not be true. They have taken away nothing and provided much to us. So as we think about robots moving forward, I wonder whether we might be able to fold them into our diverse set of relationships rather than fearing that they’re going to take away.

IRA FLATOW: You, in your book, do talk about animal robots and how people really get close to their robots even to the point of thinking about burying them like animals.

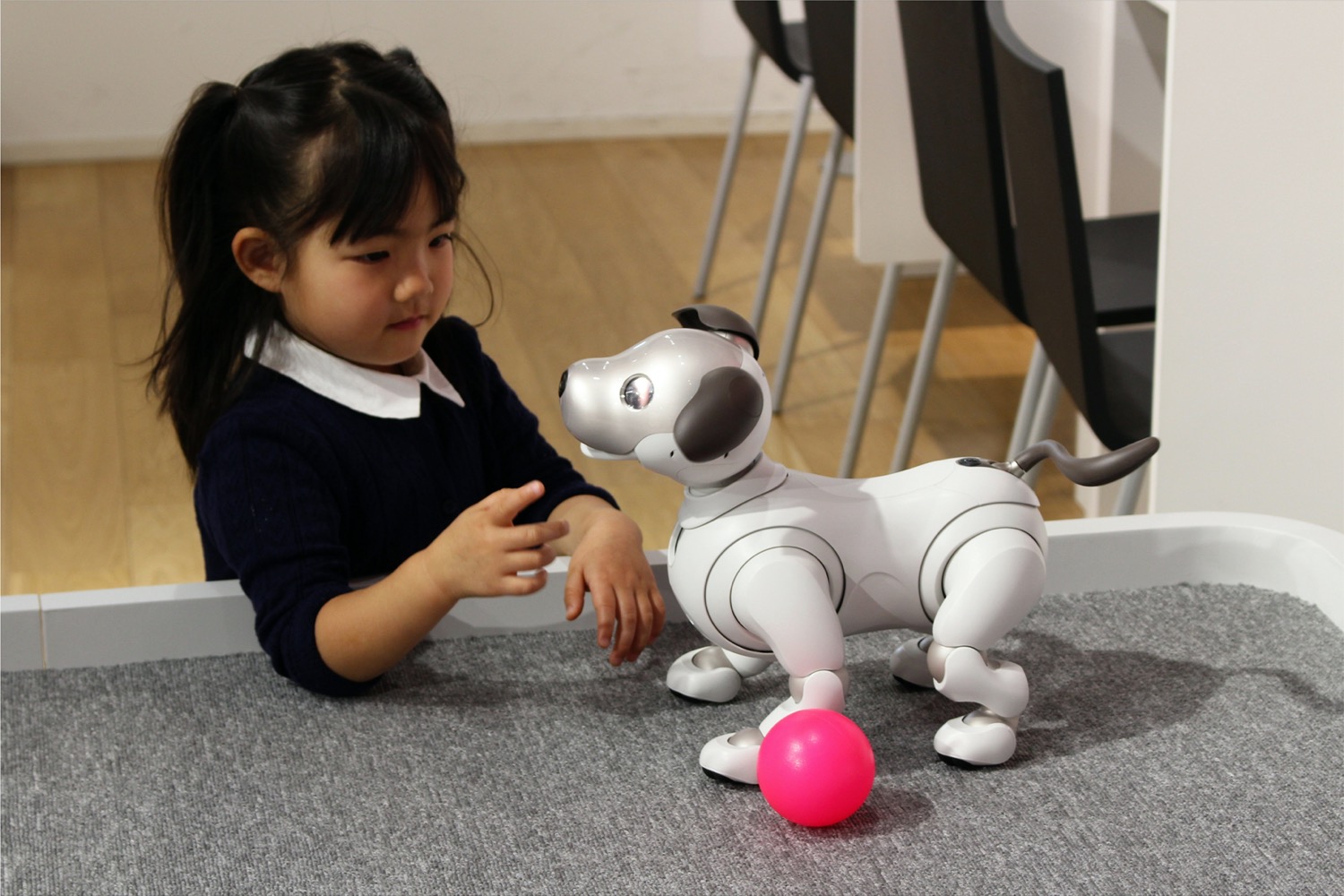

KATE DARLING: That’s right. For example, Sony had this robot dog called the AIBO in the ’90s. It was popular in Japan and in the US. And people got really attached to their robot dogs. And they did make them part of their families. And when Sony ended up pulling the tech support for the dogs many, many years later, Buddhist temples in Japan started having funerals for the broken AIBOs that couldn’t be repaired anymore so that people could say goodbye to their companions. So there’s already some anecdotal evidence.

And there’s also a lot of research in human-robot interaction that shows that psychologically we do socially relate to robots, even though we know that they’re not alive. But we can actually get something out of that relationship when we use it correctly. There’s actually this robot called the PARO. It’s a baby seal. It’s designed to be a really cute baby harp seal. It doesn’t do much. It just kind of responds to touch and makes little sounds. It gives people the sense of nurturing something.

And that robot is already being successfully used as an animal therapy replacement in a lot of contexts where we can’t use real animals. They use it with dementia patients and in nursing homes. Turns out, it has a very similar effect to a therapy animal both physiologically and psychologically. They’ve used it as an alternative to medication to calm distressed patients. They’ve been able to lower people’s blood pressure.

But a lot of people worry that this robot is there to replace human care workers. And I’m not saying that wouldn’t happen, that people might put someone alone in the room with a robot and just– and feel like they don’t have to do their job anymore. But the point is that that’s an incorrect use for the robot because it’s not there to replace human care, it’s there to replace animal therapy.

IRA FLATOW: You mentioned that in the book about some of the shortcomings that we don’t normally think about robots. In the situation that you have there, let’s say the robot is in a room and a person collapses and needs some sort of medical attention or CPR, a robots not going to be able to do that.

KATE DARLING: No, we’re consistently misled by the media and by our own biases about what robots are able to do, to think that they’re more capable than they are or that they soon will be, when, really, robots have very specialized intelligence. They can do tasks. But they cannot do what a human worker does for the most part. So this idea that the robots can come and replace care workers or replace teachers or even replace factory workers has been– it’s a pervasive idea, but it hasn’t really worked out that way in practice.

Robots have disrupted workplaces. And they’ve created different demands for how many people need to be on staff in some cases. But they can’t completely take over anyone’s job because human intelligence is much more multifaceted. We can deal with unexpected situations. We can pick up that screw that falls on the floor in the assembly line. And a robot has no idea how to deal with any of that.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, you mentioned an anecdote, a tweet that Elon Musk had to put out when he discovered that a fully robotic Tesla factory is not a good idea.

KATE DARLING: Yeah, he tried to automate his car factory. And you would think having had robots in factories for five decades or so and the fact that a factory is such a predictable and easily automated place, you would think that we would have been able to automate car manufacturing by now. And yet, we haven’t been able to. Elon Musk tried. He failed.

And it’s because precisely that there’s always something that can happen that requires that flexibility, that understanding context, that seeing that something went wrong, that requires the human flexibility. And he ended up trying, failing, and then tweeting that human intelligence was underrated. Yes, and what that means to me is that it would be much more efficient if we tried to combine the skills of humans and robots rather than just trying to automate away the pesky humans.

IRA FLATOW: One of my favorite pieces of history from this book, and I had no idea about this. I’m talking about trials for animals like sheep or pigs that did damage to property or even injured children. The trials were serious business.

KATE DARLING: Yeah, there’s this incredible piece of history. We used to put animals on trial for the crimes they committed. And it was a full on trial with a jury, with defense attorneys, that followed the same rules as having a human in court. We did this for a surprisingly large part of the Middle Ages. And it seems so ridiculous to us today to put animals on trial given that we know that they can’t follow our human morals, nor should we expect them to or punish them for not doing so.

And yet, in a lot of the conversations around robotics and artificial intelligence, I see people arguing that something can be the algorithm’s fault or a robot’s fault and even proposing that we should maybe find a way to hold robots accountable for the unanticipated harm that they cause or that we should program human morals into the machine so that they follow our ethical rules.

And ever since the beginning of the earliest laws known to humankind that we found etched on clay tablets, we have had to deal with this problem of, what happens if your ox wanders into the street and gores somebody, and you didn’t anticipate that? And we’ve always found ways to assign responsibility to the humans who were responsible for this. When we’re thinking about laws for robots and AI moving forward, we should really be looking towards some of the solutions we’ve had in the past rather than viewing this as a new problem and, of course, rather than trying to make the robots themselves accountable, which is something we automatically default to, again, because we’re comparing their intelligence to our own.

IRA FLATOW: You know, when I think about that, I think of one of the most advancing technologies today, the self-driving car. Are we going to have to hold the car makers responsible for decisions that are made by the robot inside controlling the car, the robot that is the car?

KATE DARLING: Well, the danger is that we’re going to default to not holding the manufacturer accountable, but holding the car accountable or even holding a driver accountable who was told that they need to be paying attention to the road 100% of the time, even though the robot is doing 99% of the work. So you have these handoff problems. So it is a very complex issue.

And I think the important takeaway that I really want people to be thinking about is that when you compare the car to a horse or an animal, you have a very different sense of who should be held accountable than when you view it as some science fictional robot that can make its own decisions. We should be saying it’s not the robots fault but rather the manufacturer, the trainer. We need to be looking for the accountability in the people who build these systems because we default so easily to giving the robots themselves agency.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios, talking with Kate Darling research specialist for the MIT Media Lab, author of The New Breed– What Our History with Animals Reveals about Our Future with Robots. Do you think we should be making robots that look like humans? I’m thinking of Data in Star Trek.

KATE DARLING: Data in Star Trek, oh, I had such a crush on Data when I was growing up, really one of my favorite androids. But I think my answer to that would be, generally, no. I do think that we have this inherent fascination with recreating ourselves and that we’re always going to make humanoid robots for art and entertainment purposes. And I think that’s fine.

But for the most part, I don’t think that the human form is particularly useful. People argue that we need humanoid robots in order to relate to them. We know from human-robot interaction research that that’s not true at all. You can create a robot in any shape that can be compelling and emotionally and socially compelling to people. If you even think of Pixar and animators and the way that they can put emotion into a blob, you know that something doesn’t have to have a human shape.

And then the other thing that people say is that we need humanoid robots because we have a world that’s built for humans with stairs and doorknobs and narrow passageways. But I think sometimes we forget that that’s not a world built for humans but for able-bodied humans of a certain height. And I think that if we thought a little bit more outside of the box about how we build our entire infrastructure and made it more inclusive to wheelchairs and strollers and children, then we also wouldn’t need to have these very expensive, difficult to build humanoid robots but could have robots on wheels and robots of all different sizes and shapes which would be more practical.

IRA FLATOW: What’s your opinion about who will decide our robotic future?

KATE DARLING: Well, that is the tricky part because, despite all of the headlines saying, no jobs, blame the robots, or this technology is coming and we just need to learn how to deal with it, I truly believe that this is all about our own choices as humans. And unfortunately, those choices are made against the backdrop of an economic and political system that we have in place currently.

That, to me, is the true danger, that we are going to see uses of the technology that don’t support human flourishing, that aren’t in the public good, that harm certain groups of people, because the choices are being made by the current politicians and the current corporations against the backdrop of corporate capitalism. That is not always in the public’s interest. And so I think it’s so important for us to remember that the robots don’t determine the future, that we determine the future. Whether we’re designing robots, whether we’re voting for who’s in office, I think that it’s really important to remember that we determine what this robotic future means.

IRA FLATOW: Kate Darling. Thank you so much for taking time to be with us today.

KATE DARLING: Thank you so much for having me.

IRA FLATOW: Kate Darling, author of The New Breed– What Our History with Animals Reveals about Our Future with Robots.

Copyright © 2022 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Christie Taylor was a producer for Science Friday. Her days involved diligent research, too many phone calls for an introvert, and asking scientists if they have any audio of that narwhal heartbeat.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.