How To Make Spoof-Proof Biometric Security

17:08 minutes

Nearly all new smartphones and some laptops feature fingerprint scanning, and Samsung even has 2-D facial and iris scanning. But many of those systems can be spoofed by fingerprint replicas … or even photos of faces and eyes.

Stephanie Schuckers, director of the Center for Identification Technology Research, says the next wave of biometrics will need to solve a crucial problem: How can machines verify a user’s fingerprint or face, while also ensuring that a living, breathing human is supplying the biometric?

[A new wearable aims to help people who feel socially awkward interpret others’ emotions.]

Consumer technology companies could do that by detecting moisture on the tip of your finger, she says, or by scanning a “second fingerprint” that underlies the surface print. Another possibility for circumventing spoofing may be 3-D facial scanning tech, which could be coming to an iPhone near you.

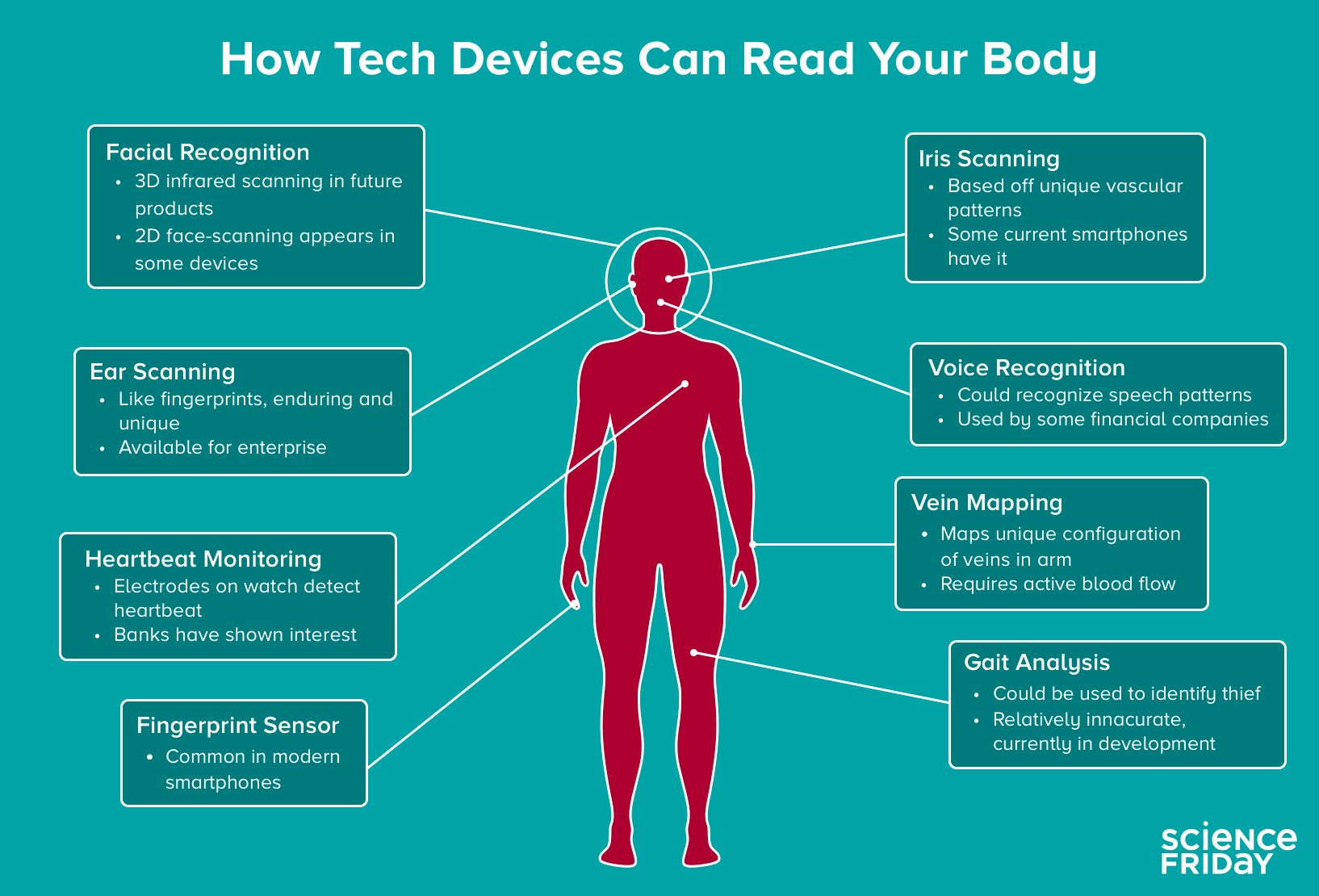

Looking ahead, the biometric frontier might include more obscure measures of identity verification, such as “ear prints,” vein mapping, or gait analysis, explains April Glaser, a technology staff writer at Slate. But she says a bigger concern with biometrics is how advertisers and the government might use them to manipulate us.

Stephanie Schuckers is Director of the Center for Identification Technology Research and a professor at Clarkson University in Potsdam, New York.

April Glaser is a technology staff writer for Slate. She’s based in Oakland, California.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. Your fingerprints are all over your phone. If you’re like me that unique physical marker can be used to unlock your smartphone too. But it’s not foolproof technology, because security researchers have already shown that you can unlock devices with a replica of someone’s fingerprint. They say that they can even swipe fingerprint data from a photo of someone flashing the peace sign. Wow.

So why not use then an iris scan? Consider the case where a hacker used a poster of German Chancellor Angela Merkel to extract iris information from her eye, which the hacker said he could print on a contact lens to spoof an iris scanner. You get the point here. As more biometric tech comes online, like 3D face scanning in your next iPhone perhaps, how can we make our machines savvy enough to know the real thing from a spoof?

Stephanie Schuckers, Director of the Center for Identification Technology Research and a Professor at Clarkson University in Potsdam, New York, is here. She joins us from WILL in Illinois. Welcome to Science Friday.

STEPHANIE SCHUCKERS: Thank you.

IRA FLATOW: April– you’re welcome. April Glaser is a Technology Staff Writer at Slate. Welcome to Science Friday.

APRIL GLASER: Thanks for having me.

IRA FLATOW: April, let’s start off with fingerprint scanning, facial recognition, they’re all pretty widely used. But there are some less conventional biometrics on the horizon, ones people may not have heard so much about. What are they? Go through a little list of them for us.

APRIL GLASER: Well, you mentioned at the beginning the ear scan. There is a company in the Pacific Northwest that can scan for the unique shape of an earlobe and that is apparently a unique identifier that none of us share– is the shape of our earlobe. And that is apparently, according to some reporting that I did last year, was being tested by some police forces, some police departments in Washington State. And they put the tech say in a body mounted camera, so that way when the police came up to the person’s window they could see someone’s ear and then match that to a database.

MasterCard has been experimenting with selfie recognition. So you take a picture of yourself and so that’s more facial recognition. We also have seen heartbeat monitoring. So these are bracelets that you wear. Microsoft also experimented with this in 2015, where you actually check out and pay with your financial information linked to your unique heartbeat. There is eye veins scanning. So it goes well-beyond the finger.

IRA FLATOW: Dr. Schuckers, anything you want to add to where we’re headed?

STEPHANIE SCHUCKERS: Yes. Some of the other modalities that we could look at– our veins. So we can look at beyond the veins of your eye, the veins in your finger, the veins in your wrists, the veins in your palm. Each of these can be used as a unique identifier. I’ve even seen the electroencephalogram. So this would be electrodes placed on your head could be used as an identifier, which might be good for wearables, headphones, et cetera.

IRA FLATOW: Now it has been rumored that the next iPhone might have a 3-D facial recognition. We don’t know but as you say, as April said, there is 3-D facial recognition already. How secure is that? Can’t people hack facial recognition already?

STEPHANIE SCHUCKERS: Yes, definitely. And so what you want to do is when you measure the biometric you also want to measure additional features that really tell you that you’re measuring it from a real person, not just a photograph or someone holding up a phone of a photograph of an individual. We call that Leibniz detection.

IRA FLATOW: Hmm. Leibniz detection. And what other things would it incorporate? Would you put your fingerprint and your face on there?

STEPHANIE SCHUCKERS: Well, what’s neat about the 3-D face, for example, is now any two-dimensional representation of a face, like a photograph, wouldn’t work any more, because you would need that three-dimensional information. So that could be an example. Other examples might be looking in the infrared, the near infrared range, because obviously you have different information present in your face in the near infrared range than you would in a typical visible spectrum photograph.

IRA FLATOW: One of the things that seems so fundamentally different about biometrics as opposed to passwords is that I don’t go walking around with my password written on my shirt, but my face is out there. My iris data or fingerprints can be swiped from photographs.

STEPHANIE SCHUCKERS: Yeah that’s what–

IRA FLATOW: Everybody’s getting their picture taken everywhere now.

STEPHANIE SCHUCKERS: Exactly and that’s what’s neat about the Leibniz detection piece, because you can put the two of them together. And that’s what you need to do the full recognition to know that it matches what you’ve stored before, in terms of the face features, but also that you just measured it from that individual and not from some kind of replica.

IRA FLATOW: April, do you see any problem with any of this stuff?

APRIL GLASER: I mean sure, and you make a great point about the fact that a password is inherently private. And the whole point is that you don’t tell anyone. And the same with a credit card, in the sense that you only have one and you have it. But yeah, when you walk around, your face is available to view. And it’s true that a photograph can be a source for biometric technology. And we see Facebook doing that, for instance. So when you put your photograph into Facebook, as do 350 million photographs that go into Facebook a day, those are all– many of them rather are being read and the faces are being read and put into their facial recognition database that they then use to match name to face.

IRA FLATOW: Our number 844-724-8255. 844-724-8255. You can also tweet us @scifri, if you’d like to get in on this discussion. Now I understand there are two kinds of biometrics, physiological and behavioral. Stephanie, what’s the difference there and is one better than the other?

STEPHANIE SCHUCKERS: They are different. The physiological is more the concrete aspects, like a fingerprint. It has a physical characteristic. Where behavioral can change depending on your behavior, like how you walk, how you talk, how you hold something, for example, how you type, how you swipe on your phone. Those are all your behaviors that then can be utilized to create a signature of yourself and utilize for biometric recognition.

IRA FLATOW: What about it being used– I’ll ask both of you. What about it being used without my permission? I mean if there’s facial recognition on my cell phone, for example, and I’m stopped by a police officer. Could he just not take my phone and point it back at my face and unlock my phone that way?

STEPHANIE SCHUCKERS: Yes, certainly. And I think that’s where we’re still in a national conversation about what are the limits. What is OK and what is not OK? And I think the public certainly is expressing their opinions on this. And it’s really up to technology and government to listen, in terms of what’s the right balance between security of your own devices, security of the country, and of course, your own privacy.

IRA FLATOW: April?

APRIL GLASER: Yes. And you know there are a couple of states that have consent laws when it comes to facial recognition in particular. And those are Illinois and Texas. So and in those states, or in Illinois particular, you’re supposed to consent to your face being matched to your name with using facial recognition technology. But in other places they don’t need your consent at all, and that opens the door for such a wide range of uses, from advertisers to law enforcement.

And we know that law enforcement, and the FBI in particular, has a massive facial recognition database that has mugshots, driver’s license photos, passport photos, all kinds of things. And so certainly, we’re at a place now, whether or not you consent to it, in most states where if they do take a picture of you they can use that to match to all kinds of records that they may have on you, whether or not those records are correct.

IRA FLATOW: Dr. Schuckers, let’s talk a little bit about– let’s get into the weeds– we like to get into the weeds here– about how the biometric data about me on my phone is kept secret and kept safe. Does it go out over Wi-Fi or my cell phone every time I authenticate my fingerprint, let’s say in a banking app, for example, or any other way?

STEPHANIE SCHUCKERS: That’s a great question, because this does get back to your comments related to privacy. The trend right now is to store your biometric data locally on the device. And most of the major mobile device companies have this capability in there.

And so what happens is it’s not really biometrics that’s doing the authentication with your bank. It’s really a 2-step process. It’s the combination of biometrics for local user verification and asymmetric key cryptography for the verification with your bank. And a lot of this is being done under what’s called the FIDO Alliance, that stands for Fast Identity Online.

IRA FLATOW: So is the password then dying a slow death here or are we always going to have passwords do you think?

STEPHANIE SCHUCKERS: Well, I think that’s a good question. I think we will have passwords for quite a while, because we need a way to be able to reset new devices. But I also think there’s a lot of people working creatively to move beyond the password. The FIDO Alliance is the first step, which means now you’re not storing your password at your relying party and using it for every single transaction. Which beyond security risks, also is a convenience issue, having to remember all these different passwords.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s go to the phones to Wayne in Georgia. Hi, Wayne. Welcome to Science Friday.

WAYNE: Hello.

IRA FLATOW: Hey, there.

WAYNE: I just I wanted to ask a question that you’re all talking about passwords that are unspoofed or not able to be. What about DNA, because see that’s something which nobody would know except you and your technical devices?

IRA FLATOW: Good question. Why not something you plug into your smartphone, a little chip, a bio chip, and you put a piece of some DNA on there.

STEPHANIE SCHUCKERS: Yes. I don’t think we’re quite there yet with DNA. DNA takes 45 minutes to an hour to process right now. So you might have to wait a while to get into your phone.

[LAUGHTER]

APRIL GLASER: Now that said, there are efforts right now to make smaller and more affordable ways to synthesize DNA, and more portable ways. But yeah, we’re just not there yet.

IRA FLATOW: Now, I know April, you’ve written about an alternative to all of this. And that is instead of using your thumb print or an iris scan to unlock a door, some companies just ask their employees to implant chips, little chips underneath their skin. Is that where we’re all going with this?

APRIL GLASER: Well, it’s one direction that some companies have been exploring, particularly outside of the United States more. Although US companies are digging more into that. But the idea there is that a chip about the size of a grain of rice is usually inserted between the thumb and the index finger. And then that can be used to say unlock a door or turn on a coffee pot, and they use various types of wireless communication to do that. The issue there, though, is that like any device, it can be potentially hacked. And a chip that’s inside of you could read a lot of sensitive information, like where you are, where you’re not, perhaps what devices you have around you or others, and therefore, who you’re with. Things like that.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s say Dr. Schuckers, someone steals a phone. I’ll put a politician’s name on that. No real name, but it’s a politician, could they somehow get the raw biometric data off there or is it secured on the phone in such a way that it’s really hard to access?

STEPHANIE SCHUCKERS: Yes, they do take extra efforts to store the biometric information and the cryptographic information, and it’s a special part of the phone, a secure part of the phone. That being said, I mean really what we’re trying to protect is scalable attacks that would be coming through the internet to your phone by doing that. If someone physically had your phone and had enough money and resources, I think anything could be hacked out of your phone. And so what we’re more interested in is the broader scope of protecting your information in these scalable attacks.

IRA FLATOW: I’m Ira Flatow. This is Science Friday from PRI, Public Radio International. Talking about what’s new in your cell phone and biometrics, and all kinds of stuff, with April Glaser and Stephanie Schuckers. Are we– every time something new comes out about facial recognition or something with a chip or something like that, I’m reminded of the Minority Report. Remember where the star of the movie walks through a mall and everywhere he goes they instantly recognize who he is, they pitch ads at him. Are we there yet, April?

APRIL GLASER: Well, we’re getting there. And that could be done to be clear without biometrics. It could be done just by reading your phone with beacons, and they can tell that you’re around. But certainly retail shops are already using facial recognition software to say find repeat customers or identify shoppers. Perhaps even more creepily, we’re seeing mobile phones now using eye gaze tracking for ad metrics, so they can see where your eyes actually land on the screen and then try to court your propensity to buy that product. And that can be seen as extremely manipulative.

And we’ve seen billboards that change when someone drives past them. So we’re seeing ads increasingly tailored to people as they walk through the world. And part of that does have to do with facial recognition and various biometrics, but a lot of that has to do with the fact that we’re just carrying computers with us everywhere and computers can talk to each other.

IRA FLATOW: Is there any way to opt out of all of it? Can you– you talked about having a chip under your skin. Could you have a chip that says, I’m opting out or you have no permission to do any of this stuff with me. Is that possible?

APRIL GLASER: There’s no universal opt out right now like that. So even if you’re not on Facebook and people put your picture on there, then your picture is on there and someone might be able to one day use that information I’m not sure how, but to link that to you. Like we were saying earlier in the program when your face is out there, it’s out there. And if you have a driver’s license then your name is connected to your face. And there are thousands and thousands of security cameras in any city and any of those cameras might be equipped with facial recognition technology. So unless you wear a mask all the time, I wish you luck.

IRA FLATOW: Well, I only have a couple of minutes left to talk about it, but let me ask you what you see as the next biometric technology coming online, that’s just around the corner.

STEPHANIE SCHUCKERS: Well, I would– You want to go?

IRA FLATOW: Go ahead, Stephanie, you can go first.

[LAUGHTER]

STEPHANIE SCHUCKERS: I would say the behavioral biometrics is more now about not necessarily a single pressing of your finger or taking a photograph, but really just that your device knows you. It knows you by how you hold it, by how you work with the device, by how you swipe and type, and maybe other wearables you may have. So you don’t really have to do anything. The device– you pick up the device and it knows who you are.

IRA FLATOW: So it’s sort of like your friend?

STEPHANIE SCHUCKERS: Yeah.

IRA FLATOW: That can’t be so and so, they don’t do that.

[LAUGHTER]

APRIL GLASER: I would agree. I think that increasingly we’re seeing companies take a constellation of things. That they can read about you whether it’s your gait, or your fingerprint, your password, and using all of these things together to know that indeed that is you. The question then becomes, how is this going to be applied. Now that they know you’re the one in the room, are they going to tailor ads to you, are they going to dig up your criminal history? These are the questions that remain unanswered.

IRA FLATOW: Scary questions and it’ll take a brave new world to deal with it. And let me thank my guests. Stephanie Schuckers, Director of the Center for Identification Technology Research and a Professor at Clarkson University in Potsdam, New York. April Glaser, Technology Staff Writer at Slate. Thank you both, for taking time to be with us today.

STEPHANIE SCHUCKERS: Thank you.

APRIL GLASER: Thank you.

IRA FLATOW: You’re welcome.

Copyright © 2017 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Christopher Intagliata was Science Friday’s senior producer. He once served as a prop in an optical illusion and speaks passable Ira Flatowese.