Making A Meal Fit For An Astronaut

12:19 minutes

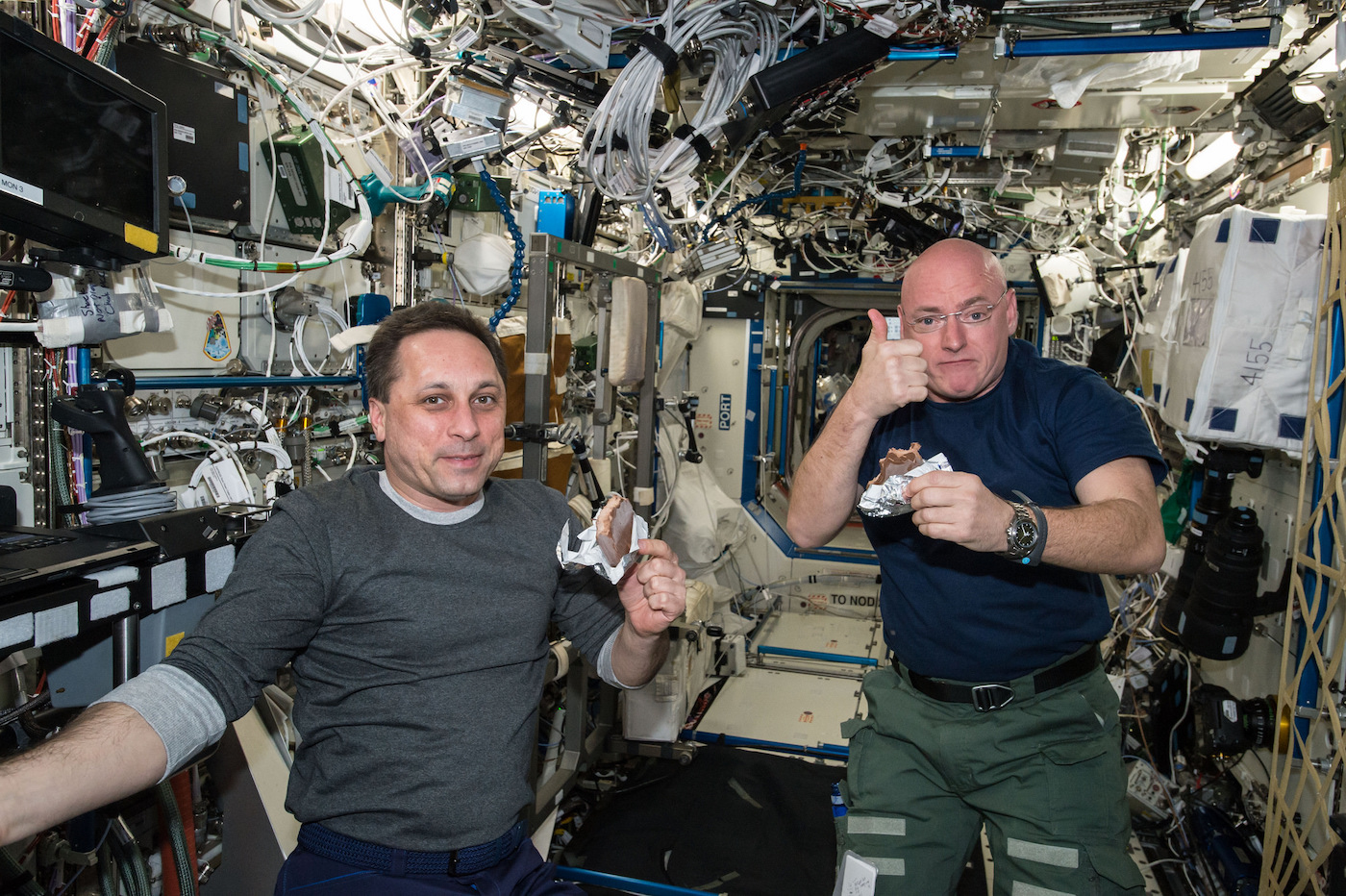

Life on the International Space Station throws some wrenches into how food and eating work. There’s very little gravity, after all. And there are big differences between nutritional needs on Earth and in space.

Astronauts must exercise two hours each day on the International Space Station to prevent bone and muscle loss, meaning daily caloric intake needs to be somewhere between 2,500 and 3,500 calories. Sodium must also be reduced, as an astronaut’s body sheds less of it in space. Astronauts also have an increased need for Vitamin D, as their skin isn’t able to create it from sunlight as people on Earth do.

So, how do all these limitations affect the food astronauts eat? Joining guest host Kathleen Davis to answer these gustatory questions is Xulei Wu, food systems manager for the International Space Station in Houston, Texas.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Xulei Wu is Food Systems Manager for the International Space Station at the Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: And I’m Kathleen Davis. If you’re anything like me, food is an important part of your life. One of my favorite things to do is to get together with friends and family and have a big delicious meal.

IRA FLATOW: And that’s good. Because with the holiday season coming up, there will be lots of that. But what do you do if you find yourself up in space, let’s say, residing on the International Space Station? Back in the day, early astronauts squeezed food out of a tube or they sucked in an orange-flavored breakfast drink.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Yes. Not the most appetizing idea. And life on the International Space Station does throw some wrenches into how food and eating work. But, Ira, today dining in space is actually quite different.

IRA FLATOW: Is it? Tell us about it.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Well, to answer some of my gustatory questions is my guest Xulei Wu, food systems manager for the International Space Station. She’s joining us from Houston, Texas.

Welcome to Science Friday.

XULEI WU: Thank you so much, Kathleen. Happy to be here.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: We are happy to have you. So I want to start with a quick clarification. Is nutrition and what your body needs different in space than it is when you are on the ground here on Earth?

XULEI WU: Yeah, actually, the terrestrial nutritional recommendations on Earth are typically used by us as a starting point for spaceflight requirement. But several nutritional requirements, they do change in space due to the nature of space travel. For example, the microgravity has negative impacts to astronauts on their bones, muscles, and the cardiovascular system.

So as a countermeasure to mitigate those effects, on average, an astronaut need to spend at least two hours per day to exercise on ISS. I’m not sure how that compare to you or our listeners, but that’s definitely more exercise than I would do on a daily basis. And of course, more exercise means higher caloric needs.

And another example is vitamin D. On Earth, our skin can synthesize vitamin D when we’re exposed to UVB radiation in the sunlight. However, astronauts are protected from sunlight exposure during spaceflight. So the requirement of vitamin D is also higher.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Can you explain to me what kind of foods are actually available to astronauts that are prepared in your lab? I mean, what might an astronaut’s daily menu, I guess, look like?

XULEI WU: Yeah. So we actually offer a standard menu to astronauts. We call standard menu. It doesn’t mean that they have to follow the menu, but more like a pantry, stocked up with 200 different food and beverage items, with a quantity between one to three for each item for crew member to pick and choose what they want to eat each day. So they can eat the same meals, but they don’t have to. Or they can choose to eat different meals and they don’t have to.

And we often hear crew members say that food is one of the few things crew member have total control over on ISS, unless their flight surgeon notice something out of whack from their food intake tracking data. And those standard menu foods account for about 80% of their food intake. Other than those 80% standard menu foods, they also get personal preference food, accounting for the remaining 20% of their total food consumption.

And I have to mention, all those food are definitely packaged and stowed at the Johnson Space Center here in Houston to prepare for International Space Station.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Are there any meals or snacks that seem to be extra popular for the astronauts?

XULEI WU: Oh, that’s actually hard to say, but we do notice a trend. Any new food item we add to the standard menu, they tend to be healthier and also more popular among crew members. One example, like mango salad, that’s a product developed by our food scientists recently. We added to the standard menu and it become a very popular product.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: So a big part of what you do is food packaging. So can you tell me a little bit about how gravity– I would imagine that’s a big factor in something that would impact how you would package foods– how does that change how you work with packaging?

XULEI WU: Right, totally. It’s actually difficult to mix solid with liquid in the microgravity environment. So what we do, we have different strategies. One thing, like the drink, the coffee, we get with crew member before they fly and find out what’s their preference on the coffee. If they prefer black coffee, with cream and sugar, then we add those pre-mixed dry powder together in the beverage pouch and send up in dehydrated form. So that all crew member need to do on ISS is add water back. Then they get their coffee with cream and sugar. So that’s one strategy.

And another strategy, like condiments. On ground, we like to use salt and pepper to flavor our food. And for astronauts in microgravity environments, they cannot really shake the salt bottle out. What we do is we dissolve the salt in water so that they can apply the liquid salt onto their food for flavoring.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Is the reason why you can’t have the granular salt because it may just go everywhere and just float around?

XULEI WU: Exactly, yeah. Yeah, we definitely try to avoid any crumbs in the microgravity environment. Because when we have crumbs on Earth, they fall onto the table, fall onto the floor. In microgravity, they can go anywhere.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: So I’m imagining no potato chips.

XULEI WU: Yes, that’s correct. No potato chips.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: OK.

XULEI WU: And even cracker. Our scientists really does a great job, identifies a cracker that can withhold this transportation process and also identify the right amount of vacuum we can apply to package the cracker, to hold the cracker in place without cracking it.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: So we’re talking about how these foods are prepared before they go into space. But once they’re actually on the International Space Station and the astronauts have this package in their hands, how do they actually prepare their food to make sure that it is ready to eat?

XULEI WU: Yeah, that’s a good question. So with the challenge of microgravity, astronauts, they actually cannot cook the food yet– cook on their own. And also, they are very busy human beings. So most of the food that we provide are ready to eat. All crew member needs to do is– depending on the food type, if it’s what we call thermostabilized or irradiated food, those are basically ready-to-eat food. The thermostabilized food can be compared as like the canned foods you can find in grocery store, except we package those in a flexible pouch so that they are less in weight and also consume less volume after consumption.

For those, crew member just need to put it into a food warmer. The food warmer on ISS, they can heat up food to about 185 Fahrenheit. And they have those clamps inside of the food warmer to hold the food packages in place and heat up the food by conduction.

And for freeze-dried food, a crew member will need to add water first, as I mentioned earlier. And on ISS, they can choose either cold water or hot water to hydrate the food before they cut open the package and eat from the package.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: So I want to talk a little bit about shelf-stable technology, which I’m sure is a huge part of what you do because you don’t want astronauts to get food poisoning. I mean, how do you avoid astronauts getting sick from the food?

XULEI WU: Yeah, that is a big part of what we do here at the Johnson Space Center. We need to make the food the shelf stable because the ISS food system is a shelf-stable food system. This is due to the logistic lead time to have the food prepared. Till the point that it can be consumed on ISS, it could be ranging between one to three years. Therefore, the food we provide has to have a minimum three-year shelf life for ISIS.

And to make the food shelf stable, we have several processing technologies we apply to achieve this goal. One example is freeze-drying. That is a process to freeze the food first. And because food are made of water– like a beef steak, that could be about 80% water. If we talk about salad, that would be even more. And freeze-drying is this process to first freeze the food, convert all the water, liquid water, into solid ice, and then we put a vacuum to the food to allow the ice, the solid ice, to sublimate into vapor, without going to the liquid phase.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Wow.

XULEI WU: The end product become very dry, very dry cake, that’s shelf stable. Without water, food become very stable.

Another technology is thermostabilizing. That’s a process where you apply heat to the food to deactivate the bacteria and some of the spores in order to make the food shelf stable, just like the canned foods we can find in grocery store.

And the third technology is irradiation. NASA actually have the federal approval to apply a certain amount of dosage, irradiation dosage, to achieve commercial sterility of food so that they don’t need to be refrigerated or kept frozen and still be good for three years.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: So I have been camping before. I have had dehydrated food before. It’s not always delicious. How does your lab make sure that the food that goes through all these processes to become shelf stable actually tastes good?

XULEI WU: That’s actually quite challenging, going through those process and also going through those heating step, to making sure the food is safe to eat. At the same time, we also need to meet the nutritional requirements. Our scientists normally play with different flavors. For example, we can add some spicy kick to the food if we have to take the salt out. So we just try to be very creative and make sure the food still tastes good.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: The food and the act of eating can really be such an important part of life for a lot of people, and people across cultures too. How is this recreated in space?

XULEI WU: Yes. So first of all, we try to provide as diverse standard menu as possible, trying to accommodate astronauts with different background and culture. At the same time, we also work very closely with our international partners, like the Japanese Space Agency, ESA Space Agency, et cetera.

Normally, when they have their crew member flying, they will be sending some specialty food as well to allow crew member to share those unique food on ISS.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Xulei Wu is food systems manager for the International Space Station. She’s joining us from Houston, Texas.

Thank you so much for joining us. This was a great conversation.

XULEI WU: My pleasure. Thank you so much for having me.

Kathleen Davis is a producer and fill-in host at Science Friday, which means she spends her weeks researching, writing, editing, and sometimes talking into a microphone. She’s always eager to talk about freshwater lakes and Coney Island diners.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.