How Much Worse Can The Measles Outbreak Get?

11:42 minutes

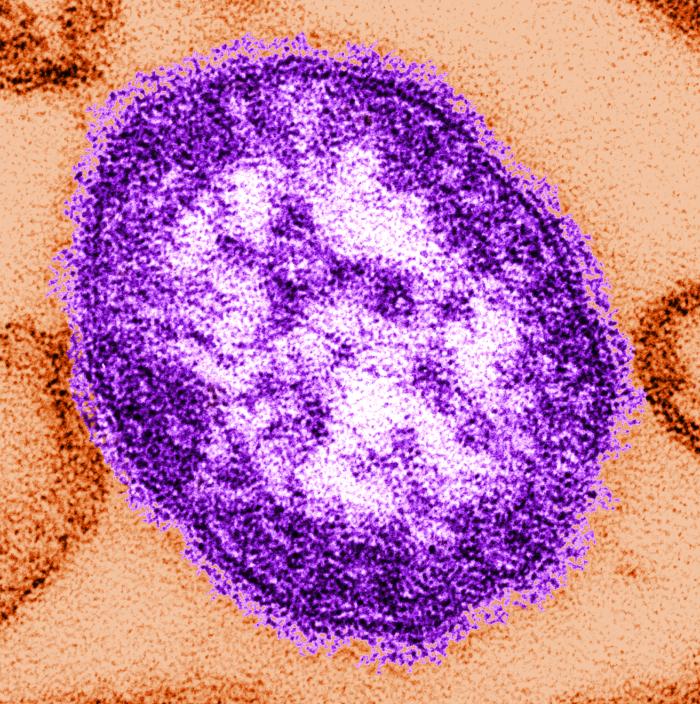

Back in 1963, before the development of the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine, there were 4 million cases of measles every year. It took nearly four decades, but by 2000, enough people had become vaccinated that the measles virus was eliminated in the U.S.

But since then, the ranks of unvaccinated people have grown, and the measles virus has been reintroduced into the U.S. This week, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) officials report over 600 cases of measles across 22 states. That number may seem small compared to previous decades, but it also should be noted that one in every thousand cases will develop a fatal complication of encephalitis, or a swelling of the brain. Some medical professionals say that it is likely that sooner or later, for the first time in 20 years, someone in the U.S. will die from this disease.

Dr. Saad Omer, professor of Global Health, Epidemiology, and Pediatrics at Emory University joins Ira to answer questions about the current outbreak, including how much worse conditions could get.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Saad Omer is a professor of Global Health, Policy and Pediatrics at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. A bit later in the hour, the poetry of science, poetry about science, and what it means to bring the two under one roof.

But first, back in 1963, before the MMR vaccine existed, there were four million cases of measles every year. And it took nearly four decades, but by 2000, enough people had become vaccinated that we had eliminated the measles virus here in the United States. But since then, the ranks of the unvaccinated have grown, and the measles virus has been reintroduced into the US.

This week, the CDC official report has reported nearly 700 cases of measles across 22 states. Might put a little perspective on that number. Considering that one in every 1,000 cases will develop a fatal complication of encephalitis, a swelling of the brain, it is likely that sooner or later, for the first time in 20 years as the number of cases grows to about 1,000, someone in the US will die from the measles.

We all need to take this measles outbreak seriously, and that starts by getting the facts right. How is the virus transmitted? How do you know if you’re still immune? Who is most at risk of infection, and how much worse can this outbreak get? Here to share the facts with us is Saad Omer, professor of global health, epidemiology, and pediatrics at Emory University. Dr. Omer, welcome to Science Friday.

SAAD OMER: Thank you. Glad to talk to you.

IRA FLATOW: You know, we’ve been hearing about the measles virus almost every day now. This week, a case of measles reached two California universities and public health officials ordered a quarantine for hundreds of students who couldn’t prove that they had been vaccinated. Just how bad can this outbreak get?

SAAD OMER: So I don’t want to be unnecessarily alarming, but I am concerned. In 2016, we looked at what proportion of the US population is protected against measles, and we applied a slightly different approach. So usually when we look at vaccination rates, it’s a snapshot. And we don’t generally take into account those who are already unvaccinated and those too young to be vaccinated.

And what we found was that at that time, around 2016, 2017, in the US, our protection levels were hovering close to the so-called herd immunity threshold– i.e. the threshold of protection at the population level below which you start seeing outbreaks, et cetera. So since we were close to that, we remain concerned. But this is not inevitable. There are things we as a country and the community can do.

IRA FLATOW: Is there though a tipping point that we need to look out for? A number that if we reach it it’s going to make it really harder to come back from this?

SAAD OMER: So probability takes over or stochasticity takes over when you’re close to these numbers for two reasons. First of all, that coverage or vaccination rates are not homogeneous across the country or across populations. And so there are [? subpopulations ?] that have higher rates and other populations where you have clusters of even lower rates. And so what you start seeing is larger and more frequent outbreaks as you approach that number at a broader national level. So that’s what we are seeing, and that’s a little bit concerning.

So unfortunately, it’s not that a single number. But as you get close to that number, you start seeing these phenomena happening.

IRA FLATOW: OK. You mentioned the word herd immunity. We’ve heard it we’ve heard herd immunity quite a while. Give us a definition of that terminology.

SAAD OMER: So a simple definition is that if you protect a certain proportion of the population, the virus or a bacterium, depending on the disease, doesn’t find enough susceptible peoples to take hold in that community. So if you introduce a case, the epidemic dies out almost on its own. And so that’s the level of protection at the population level. The percentage protected is called the so-called herd immunity threshold.

And the broader phenomenon that a fraction of population or a proportion of population is protecting everyone, including those who are too young to be vaccinated and are not vaccinated due to immuno-compromised status. That overall phenomenon is called herd immunity or community immunity or herd protection.

IRA FLATOW: All right. Let’s go through some of the questions people have. First of all, does the vaccine you get when you are a baby ever go away?

SAAD OMER: So we don’t have any evidence of waning immunity against measles. And so we should be protected for a long, long time, if you have followed the schedule accordingly, especially if you have gotten two doses of vaccine in your childhood. So our evidence suggests that, at least for measles, this waning immunity phenomenon is not much of a concern.

IRA FLATOW: I’ve heard of people who have said that they have gotten two doses of their vaccine and they’ve gone to their doctor to see if they’re immune and they are no longer immune. There are millennials no longer immune.

SAAD OMER: So at the population, that’s a different phenomenon. But even our most effective intervention in any field are rarely 100% effective. And so there will be a small fraction– and the good thing is, with two doses, the efficacy and effectiveness of measles vaccine schedule as a whole is 97%. So when you’re talking about 97%, there will be a small fraction, which even after two doses will not be protected. But that’s less of a concern in terms at the population level policy, et cetera, and from a public health perspective than to get people two doses.

IRA FLATOW: Are you ever too old to get the vaccine?

SAAD OMER: No. So you can get vaccine at pretty much any age after you become eligible. So you become eligible after 12 months under routine circumstances. And there are situations, for example, when a baby is traveling where you give the vaccine a little bit earlier than the 12 month– the first dose that is given before 12 months, and certain outbreak situations. Generally if you’re getting the vaccine on schedule, you are not too young to get it after 12 months and not too old to get it if you’re getting it a little bit later.

IRA FLATOW: I’ve also heard that if you were born before 1960 or so, you’ve probably been exposed to the virus and therefore you are naturally immune. Is there any truth to that?

SAAD OMER: Yes, there is. So we in this country have this concept of evidence of immunity. So the CDC, based on evidence from epidemiological studies and other evidence, suggests that broadly four criteria for evidence of immunity. First of all, if you have written evidence that you have received the required doses for your age and your risk status. A lab confirmation of your immunity or lab confirmation of you getting the measles virus.

The fourth criterion is if you were born before 1957, and so that’s the cutoff we use in this country. And the understanding is that there was a lot of measles there.

IRA FLATOW: New York has more cases than in any other state right now, over 600, and state legislators are saying it’s time to crack down on people receiving religious exemptions for the vaccine. This is New York state assemblyman Jeffrey Dinowitz.

JEFFREY DINOWITZ: Whatever concerns people have with the vaccines I think are overridden by the public safety concerns. We have to do everything we can to save lives and protect children and protect people in general. And making New York a state where only medical exemptions are allowed is one way to do that.

IRA FLATOW: Dr. Omer, do you think that tightening restrictions for exemptions is going to improve vaccination rates?

SAAD OMER: So starting in 2006, my group and my colleagues and others then subsequently started looking at what is the nature of these laws. Does that impact your vaccine refusal rates and disease rates? And we found that the tighter these restrictions, the more effective they are in reducing vaccine refusal rates and even disease rates for diseases that people have looked at or infectious diseases people have looked at.

In case of elimination of all non-medical exemptions, California is the first state that has tried in 35 years. We do know that tightening exemptions work. California’s initial indication is that they did improve their immunization coverage, but the picture is a little bit nuanced because they had an administrative crackdown on the abuse of these exemptions, even non-medical exemptions. And so therefore, it’s hard to say that it was eliminating non-medical exemptions that increased it.

But nevertheless, there are other modes that states can use and have used. For example, adding a requirement to go to your physician to discuss the risks of non-vaccination for yourself or your baby and others that have been shown to be highly effective in certain states.

IRA FLATOW: Now we’re talking about the MMR vaccine. Of course, the other two letters and that is mumps and rubella, correct?

SAAD OMER: Yes.

IRA FLATOW: Is there any sign it says people are not getting the triple in one dosage that those other two– mumps and rubella– might come back or be on the rise?

SAAD OMER: So in this country, we use this [? trial ?] [? in ?] [? vaccines. ?] In fact, there’s an option of adding a fourth antigen in the same vaccine that some people get, the [? various ?] [? element. ?] So they are getting those. Especially if they’re getting measles vaccines, people are getting the other two as well.

But mumps, here we think there is a waning immunity concept playing a role in increasing the risk of outbreaks, let’s say, in young adulthood, et cetera. Rubella is– we have been OK overall in terms of rubella. So of the three, we are concerned about measles for other reasons, such as refusal, et cetera. For mumps, waning immunity may maybe playing a role.

IRA FLATOW: One other question about how contagious is it. If you’re in the same room with someone who is contagious or even if that person has left the room, can you still get– can still get it?

SAAD OMER: So I don’t want to be a sci-fi scenario, but unfortunately measles is a very unforgiving disease. And so the reason why it’s unforgiving is that it hangs out in the air itself for up to two hours. And then beyond that, if on the surface. So if someone has left a room for a couple of hours, the risk is pretty high of that transmission. And it is one of the most infectious common diseases that we know of.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. So I see why then people are really pushing to getting the vaccination is the way to stop this.

SAAD OMER: Yeah, exactly. So none of this is inevitable. We have for certain diseases, we have vaccines that work overall but are not super effective. Here we have really super effective vaccines available. So we have a solution, which is to get vaccinated. And if you are eligible for two doses to get the full schedule.

IRA FLATOW: Well, we’ve run out of time. I want to thank you very much for taking the time to be with us today. We might get back to you, Dr. Omer, because we’re going to be tracking this story as the measles outbreak continues, hopefully not very much longer. Do you expect to see any signs it might go down? We’ll get back to and ask you about that. Dr. Saad Omer, a professor of global health, epidemiology, and pediatrics at Emory University.

Copyright © 2019 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Katie Feather is a former SciFri producer and the proud mother of two cats, Charleigh and Sadie.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.