How Artists Made Code Their Paintbrush

28:01 minutes

A series of lines on a wall, drawn by museum staff, from instructions written by an artist.

A textile print made from scanning the screen of an Apple IIe computer, printing onto heat transfer material, and ironing the result onto fabric.

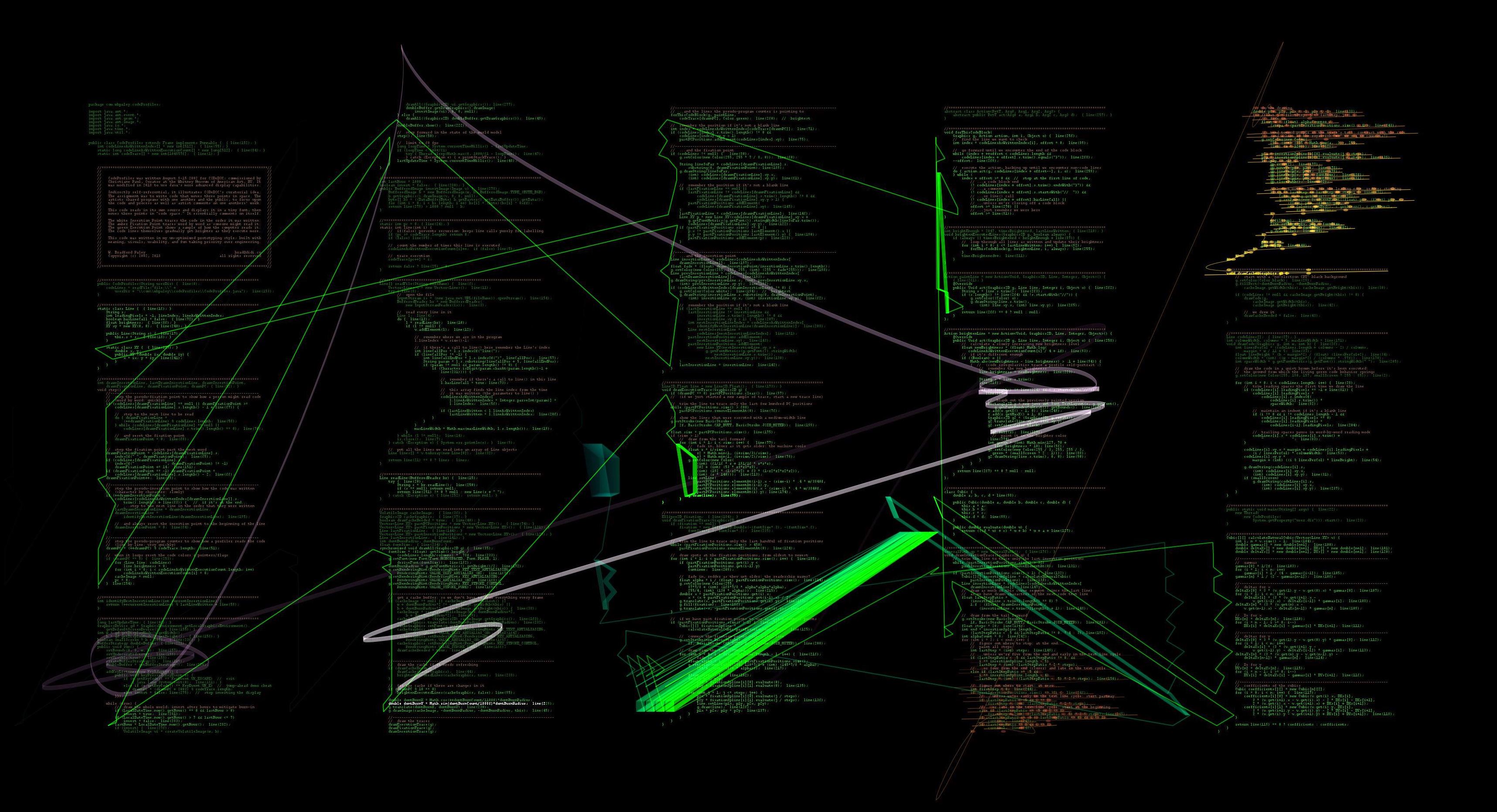

A Java program that displays its source code—plus the roving attention of the programmer writing that code, and the even speedier attention of the computer as it processes it.

All three are works of art currently on display at the Whitney Museum of Art’s ‘Programmed’ exhibition, a retrospective of more than 50 years of art inspired or shaped by coding. Contemporary examples of digital art stretch into sophisticated software, virtual reality, internet art, and even genetic and biotech projects.

Host John Dankosky is joined by Whitney adjunct curator Christiane Paul, plus artists Joan Truckenbrod and W. Bradford Paley, to discuss the analog roots of digital art, how artists have approached their partnership with computers, and how art can emerge from technological innovation.

Below are some of Truckenbrod’s and Paley’s work featured in the exhibition.

Joan Truckenbrod’s Curvilinear Perspective was a multi-step work of digital art produced in the late 1970s. Truckenbrod first programmed patterns into an Apple IIe computer, then held the computer upside-down on a scanner to print the image on heat-transfer paper—which she ironed onto fabric for the final, textile result.

Truckenbrod remains a prolific digital artist, and some of her recent projects include weaving textiles on a digital loom, and video sculpture. This 2004 work, Against The Current, features video of salmon runs synthesized with video of a human body, all projected onto a hospital bed.

W. Bradford Paley describes himself as a cognitive engineer by trade. His 2002 work CodeProfiles is meant to be a work of art and explanation. Through colored lines, it guides viewers through the systematic attention of the programmer writing the code, the “mind” of the computer as it very rapidly processes that code, and juxtaposes both to how a novice might read the same code: line by line, from left to right. Paley says he wants the work to reveal how “code grows from the inside like poetry or a novel.”

Check out some of Joan Truckenbrod’s work on her website.

W. Bradford Paley has more information about his work on his site.

The ‘Programmed’ exhibition at the Whitney Museum of Art is running in New York City until April 14, 2019.

Christiane Paul is the Adjunct Curator of Digital Art at the Whitney Museum of Art, and a professor of Media Studies at The New School in New York, New York.

Joan Truckenbrod is a digital artist based in Corvallis, Oregon.

W. Bradford Paley is a digital artist based in New York, New York.

JOHN DANKOSKY: This is Science Friday. I’m John Dankosky. When I see something really cool or interesting out in the world I do what a lot of people do. I get up my smartphone, I open Instagram, and I take a picture, and I scroll through all the different filter options to shape the photo into a piece of what I consider to be digital art. My phone helped me make it, a programmer created filter options that I chose from, the final result is mine to share with the world, even if it’s not really all that interesting.

Now, we take this ability for granted today, but the history of digital art stretches long before Instagram and iPhones. Early computer artists had to learn to code by hand to create digital images that they could not immediately see on the screen. And conceptual artists, like Sol LeWitt, were creating elaborate instructions, like draw this number of lines on a wall at these angles and letting museums produce the final results. There are those who would argue that even virtual reality has its roots in cave paintings. Here to talk about this long digital history and take us into the future are Christiane Paul, adjunct curator of digital art at the Whitney Museum of Art here in New York City.

Christiane, welcome to the show.

CHRISTIANE PAUL: Hello, thanks for having me.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Also with us is W. Bradford Paley, a digital artist and cognitive engineer living in Willsboro, New York, and he joins us in our studio as well. Brad, welcome.

W. BRADFORD PALEY: Pleasure to be here. Thank you.

JOHN DANKOSKY: And Joan Truckenbrod is a digital artist living in Corvallis, Oregon. Joan, thanks for coming in and joining us today.

JOAN TRUCKENBROD: Thank you very much. I’m delighted to be here.

JOHN DANKOSKY: And you can see some of the examples of the art that we’re talking about on our web page, ScienceFriday.com/digital. And I do encourage you to do that. To our listeners, what’s your favorite use of technology in art that you’ve seen or that you’ve used? Our number is 844-724-8255. That’s 844-SCITALK, or you can always tweet us @SCIFRI.

Christiane, I guess I’ll start with you, because you’re curating this exhibit at the Whitney right now that looks at the last 50 years of digital art and what came before, especially where code and instructions are concerned. Why did you think this was a necessary project? Tell us about the way you created it.

CHRISTIANE PAUL: The motivation for it was actually twofold. On the one hand, we are living in an increasingly encoded algorithmic world, so we’re communicating with our smart devices. We’re on social media, economics are dominated by algorithms, and I thought that it would be really important at this time to look at artists who, for a long time, have really explored the potential and the limits of rule-based and algorithmic art and look into how we express ourselves creatively through that. And the other motivation was really to counteract the assumption that digital art is something that happened in the ’90s, earliest, while it really has, as you say, a long, long history.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Maybe you can give me your definition of digital art. If people ask you, what exactly is this, what do you say to them?

CHRISTIANE PAUL: It’s not an easy one, because technologies and practices have been fluctuating so much that it’s hard to get it under one umbrella. I’d say that it’s art using digital technologies as a medium. That is very important to me, making use of the computational, real time, interactive, generative characteristics of it, and reflect on them. So it’s very different from using digital technologies as a tool to print a photograph, for example.

And in the narrow definition, people have often said it’s born digital art, it’s created, stored, and distributed via digital technologies. But that would leave out early practitioners– computer drawings from the ’60s or Joan’s work, for that matter– and that by younger artists who today often create very material works, such as weavings, that would not exist without the use of algorithms and digital technologies.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Joan, maybe I’ll go to you for that broad question, because I’d like to talk specifically about your work in just a moment. But maybe you can give us a definition in your mind of what digital art is.

JOAN TRUCKENBROD: Yes. I think it’s really an integrated media and it facilitates an integrated creativity, and by that I mean you can create a variety of forms. The artist really gives form to the artwork. The medium doesn’t create the form. Digital data, of course, can be sound, image, motion, all of those kinds of things and all of those kinds of expressive forms.

And also, there’s this simultaneity of multiple layers of realms of creative expression. So the digital artwork is in the data in the computer. It also can be simultaneously in virtual reality and it can also be in physical form. So there’s this complex layering of the simultaneous expression through these different realities, I would say.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Brad, how about you? Do you have a definition that you use?

W. BRADFORD PALEY: I think you’ve heard a couple of excellent definitions by people who are more qualified than me at defining them. I just make objects and they can be taken as art, or as tools, or as one woman once looked at something of mine and said, I don’t know what I’m looking at, but it’d make a nice scarf. And as far as I was concerned, that was perfectly fine.

JOHN DANKOSKY: But that’s important, and maybe we’ll get back to this more with you. But you’re not necessarily creating something that people might say it’s art, but other people might look at something that you’ve done that you didn’t expect to be art and they say, that’s beautiful. I find that to be art.

W. BRADFORD PALEY: As a matter of fact, Christiane and I met because I made a structuralist literary textual analysis tool, called TextArc, and it got written up in The New York Times as a piece of art. And I imagine you saw it either– you may have seen it before that at that time. And Christiane said later, I’d like to commission you to do an artwork. And I said, but that wasn’t art. That was just a tool.

And I’ve come to learn that I’m not the person who’s qualified to apply that word “art.” I pondered it for two decades as a kid and didn’t come to an answer, and I’m glad other people have an answer now.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Well, I want to get into some specific examples, and we’ll get to some of your phone calls in just a moment too, as we talk about digital art. Joan, one of the works you have on display at the Whitney is one you made back in 1978, and it used an early version of an Apple personal computer. It’s a textile, but the process to make it sounds pretty involved. Maybe you can explain exactly what you had to do in 1978 to make this tactile piece of digital art.

JOAN TRUCKENBROD: Yes. My interest was in, and continues to be, in sort of invisible processes, invisible phenomena in the natural world that are physically palpable, so playing between these realms. I programmed, using mathematical descriptions, of like wind currents or light waves reflecting off of irregular surfaces.

I embedded those in algorithms and then wrote code for the Apple IIe, which had to be in BASIC at that point. And in order to get it onto textile, the monitor was turned upside down on a 3M Color-In-Color copier, which had a backlight setting. So it understood the image on the monitor. And it used dye sheets with magenta, cyan, and yellow, and it would create color prints of each in a series of images that reflected this ongoing process in time.

And I printed them on heat transfer material. So after I had the series printed, and one– there are always artifacts of the process in the media. So one interesting thing that was happening is monitors didn’t like to be upside down. So sometimes there would be a little bit of color fading, as if the color was shifting into one corner or such, and that became part of the artwork. So each of these images on heat transfer material was cropped down and then hand-transferred onto the fiber by using a hand iron.

The fiber was a polyester satin, because the dye was micro-encapsulated and actually melted into the polyester fabric. So each of these panels would then be hand-ironed. And in that piece, I superimposed another pattern of flow on top by cutting up each panel of the print into a new pattern, and then arranging them, and hand-ironing them onto the fiber. And once in a while the image of the hand iron would appear in the piece, but for me it’s important that the hand is part of the artwork.

JOHN DANKOSKY: It’s such an interesting involved process that you had to go through to do something that starts with code. I guess I should ask you, as an artist, when did you think I need to learn to code, I need to learn how computers work in order to make my art?

JOAN TRUCKENBROD: Well, initially I was interested in making an impression or an experience of these invisible phenomena that I felt and I discovered that there were mathematical descriptions of these. So in order to then make a mark or a line drawing, I understood that I had to develop algorithms and write code. So I took two semesters of FORTRAN programming language before I began and then had to learn the process of writing code for the Calcomp pen plotter.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Brad, I’m wondering, could you tell us a bit about your early relationship with computers, and design, and how you began in this world?

W. BRADFORD PALEY: Yes. Strangely enough, I was 13-years-old in 1973 and there was an experimental Teletype terminal in my high school connected to I believe it was Cornell University’s mainframe. I was in Michigan. And somebody sat me down and said, here’s the BASIC language– we share that, Joan and I– do something, and I’ll tell you what you should be doing later. It was the teacher.

And the first thing I did was I printed a bunch of Ms, and then I said, well, let me see if I can print a circle. I knew the– I knew how– I measured how many characters away I was from a center on the page in my head, and then plotted an M, and I noticed that was squished into an ellipse, because letters aren’t square. So I corrected for that by just measuring it and putting in a correcting factor.

And the circles were boring, so then I did algorithmic stochastic shading. I picked an arbitrary point on the circle and said, don’t draw Ms there. And the farther away from that point you get, draw more and more Ms, so it looked like a specular highlight, as they called them in computer graphics. And so this 13-year-old is doing all this stuff.

And then I was told very clearly by my teacher, that’s not what computers are for. They’re for writing amortization tables, which killed my interest for about a decade. And then I got back into it in college.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Well, I have to have ask Christiane. How did the art world take in the idea of computers? Because you here you have a couple of artists who clearly were inspired by the idea that they could do something using computers. But maybe you can talk about that early history, because I’m sure not all artists had the same reaction or relationship to computers.

CHRISTIANE PAUL: Well, the artists I know, and some of them are in their 90s, were really intrigued by the potential of code of algorithms, of writing it, of computing. So they just got into it with passion. The art world hasn’t been responding that well over the decades, so it comes in waves.

Digital art had a notoriously conflicted relationship with the art world at large, so some of the early coders tell me anecdotes about tomatoes being thrown at them when they exhibited their work. There are all these prejudices of it’s done by a machine, there’s no artistic hand in it, it’s pure automation, it’s cold, et cetera. And right now I think we’re once again in a wave where you see digital art increasingly accepted within the art world. We’re living in an increasingly digital world and art has a lot to say about it. So I think it’s only natural that the integration into the fine arts world is happening a little bit more.

JOHN DANKOSKY: We’re talking about digital art, and you can join our conversation– 844-724-8255 or 844-SCITALK. I’m John Dankosky, and this is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. Let’s go to a caller here.

Kevin is calling from Berkeley, California. Hi there, Kevin. I’m sorry, Kevin, go ahead.

KEVIN: Hello.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Hi there.

KEVIN: Yes, I had a comment and a thought. Back in the ’50s, John Cage was using the I Ching as a binary system of generating random operations so he could randomize the processes that he was using in his compositions. And first of all, I Ching itself is a binary process of generating meaning and content, and specifically, very emotional, or imagistic, or even social commentary based on binary permutations.

And so John Cage got so into this that he was having people throw the I Ching constantly for him so that he could just look up stuff and then randomize his compositions. And eventually, he got around to writing a program that did it for him. And this was very well-accepted in the art world, because John Cage was pretty much a high priest within the pop movement.

JOHN DANKOSKY: And Kevin, I’m going to break in, because Christiane wants to say something. And thank you for that. And I love talking about John Cage. Go ahead.

CHRISTIANE PAUL: Yeah, thanks so much, Kevin, because this is really an excellent example. And this is what the Programmed exhibition really is about, building those connections to the practices of Cage and others. But I also have to say that people who accepted Cage, of course, we’re not necessarily seeing that work as digital. And Kevin is absolutely right about the strong connections to the program and to digital art, but, for example, Fluxus and other artistic practices at the time all used instructions and rules. And what we want to make clear with Programmed is precisely that there was a deep connection between these practices.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Joan, I want to go to you and talk about how you’ve been responding to new digital technology, new materials over time. Obviously, you’re not still flipping over old Apples and scanning them. How has your work evolved as technology has evolved?

JOAN TRUCKENBROD: Yes, I have been able to adopt new technologies. And I’ve done digital painting, different kinds of digital photography, and visual image manipulation. I’m doing a couple of things now that involve digital processes.

I have a new digital loom, which has been a challenge, every bit as quirky as computers I would say. And that’s one interesting thing of working with technology is the abilities. You develop abilities to do a lot of problem solving.

But I’m using images from underwater and images– I’m creating digital compositions of the light slats in the atrium at the Met combined with images of my warp. And then I have been weaving those images with various colors. And it’s very interesting, because it goes back to visual color mixing of the pointillist and so on.

So that has been one aspect of my current studio practice. The other is extending these digital image compositions into lithography, and I’ve been working with a master printer in Portland, Mark Mahaffey, and we have been doing some lithography involving both hand-drawn scientific– sort of pseudoscientific– diagrams and images that I’ve worked on the computer. I construct small Mylar houses with the windows and the doors drawn, and it relates to the current housing crisis, both for homeless and low-income. And then I do– I blow soap bubbles into these homes, and they sort of come out and overflow, and you can see the soap bubble geometry. And so I work on those on the computer and then they’re printed.

We’re using a handmade Kitakata Japanese paper.

JOHN DANKOSKY: It’s amazing, the old and new technologies you’re able to blend. We’re going to talk more with Joan Truckenbrod, a digital artist who lives in Oregon. W. Bradford Paley is here as well as is Christiane Paul. They’re all part of a Whitney Museum of Art exhibition about digital art, which we’re talking about here on Science Friday.

This is Science Friday. I’m John Dankosky sitting in for Ira Flatow. We’re talking about digital art, computer art, internet art, art that’s emerged from creative uses of new technology over the past 50 years or so. Things like advanced computer graphics and virtual reality, but also video sculpture, digitally produced tapestries, art built from social media, and a lot more. Christiane Paul is adjunct curator of digital art at the Whitney Museum of Art here in New York City. There’s a big digital art exhibition they’re happening right now.

W. Bradford Paley is a digital artist and programmer who lives in New York. He joins us in studio. And Joan Truckenbrod is a digital artist who lives in Corvallis, Oregon.

Brad, the piece that you have in the exhibit called, Code Profiles, is– it’s one of the first times I’ve looked at a piece of Java code and thought, this is beautiful. This is gorgeous. Maybe you can explain exactly what this piece is and how it works.

W. BRADFORD PALEY: Sure. I guess I’ll start with what it physically looks like. It’s a 77-inch 4K OLED monitor, which unpacked for normal people is– think of a three foot high by five foot wide piece of glass. What I did with that monitor– I’m very pleased with how far technology has come, because it really does just look like glass.

It doesn’t look like video. It doesn’t look like film. I just wanted the information to be foregrounded. I’m not talking about the medium. I’m talking about what you can see through the medium.

So on that piece of glass I put five columns– just like in a newspaper– five columns of text. Those five columns are the Java program you were talking about. That’s the Java program, in fact, that was my response to Christiane’s– earlier I said Christiane commissioned a piece from me after seeing TextArc. So Code Profiles was, how do I move– the commission was, you’re an artist. Move three points in space, do what you like with that.

But I want to– this is Christiane speaking and I’m going to terribly paraphrase you– but I want to show people where computer art comes from. So I’m going to show them your Code first and then they can click on it and see what you did with the three points. She was trying to demystify the process of coding and where computer art came from.

So I was lost for a while. I was used to hundreds of thousands of points, because I do data visualization and find beauty in the relationships of those. Until I realized, well, wait, Code is a space, which is why I put those five columns of code on the screen. Now I just had to figure out how I move three points through that space.

So if you see this thing– and there’s a picture of it on the web too that people could look at if they want to. But there are five columns of text, and the three points that I moved through are your fixation point, which is what scientists would call where your eye looks as you’re reading. So there’s a simulation of your fixation point plodding through the code, because that was one of the points of the exhibition.

There’s my insertion point, which is how I type the code. And I think that’s one of the key things that I’m pleased that the exhibition and the piece brings forward. My insertion point doesn’t plod through the code from beginning to end. I’m not Shakespeare. I didn’t imagine the whole thing in my head and then commit it to paper later.

Code grows like any humanist writing. It grows from the inside out, and so there’s a little bit– so I’ll write two or three lines in the lower left-hand corner, and then go conform something in the upper right-hand corner, and then the middle. And then the third point is the execution point, how the code is executed by the computer.

JOHN DANKOSKY: And you actually can see these lines cascading across the screen as a computer would read it did. Did he did he respond appropriately, Christiane, to your prompt?

CHRISTIANE PAUL: Oh, absolutely. I kept it deliberately vague, and I am really fascinated by that piece. My background is in literature, and this idea of having the reader, the writer, and the machine all in the different ways reading and executing was so beautiful to me. And also, having the code itself that renders the code to the screen as the actual work was just fascinating.

JOHN DANKOSKY: We got a tweet from John here who says, I think video games don’t get recognition for their art. Some of them are really beautiful. And at least some video gaming is represented in your exhibition.

CHRISTIANE PAUL: Yes, and I absolutely agree there’s a lot of game art and there are video games that themselves could be recognized as art, and institutions, such at MoMA, has already started collecting it. So I think it is indeed true that that’s under recognized. The piece you’re referring to I think it’s Lorna by Lynn Hershman Leeson, probably which has similarities to a game in that you navigate the story-making choices on a remote control and it unfolds on a video monitor. And it’s really a predecessor of things like Bandersnatch, the latest Black Mirror episode on Netflix, which you navigate. Someone has actually done a breakdown of Bandersnatch, a diagram of it that you can easily find when you Google it, which looks very similar to the initial drawings that Lynn Hershman Leeson did for Lorna, her piece.

JOHN DANKOSKY: I want to get to some phone calls as well, because a lot of people wanted to join us. Let’s go to Rosie, who’s calling from Wisconsin. Go ahead, Rosie.

ROSIE: Hello. My son-in-law, Mark Abell, used to do kaleidoscoping, whatever picture you happen to have, with a digital program. The program he wrote for Apple was called Kaleidoverse. I don’t know if it’s still available or not.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Oh, interesting. And so this is yet another way in which we can– we talked about this, Brad, at the top of the segment. There’s so many ways in which people can apply technology and then make their own art at home. I’m wondering, as we have this conversation about digital art amongst artists– you’re on the fence about whether or not your work is art or not sometimes– but maybe you can talk about that, about all of the things that are available to people now to create art at home.

W. BRADFORD PALEY: Sadly, because I started coding in ’73 at 13, and when I sat down and I typed, code came out, and half the time it worked. I’m the worst person to talk to about tools. I tend to prefer to write all my own code from scratch, because it leaves– when Photoshop released Drop Shadows you could see the Photoshop drop shadow– five pixels down, four pixels to the right– on everything, and it was helpful.

But when desktop publishing happened it didn’t actually improve people’s ability to express everything. It just brought up the level of mediocrity. And I’m aspiring to break out of what the tools help you do. Does that make sense?

JOHN DANKOSKY: Do you have a thought, Christiane?

CHRISTIANE PAUL: Yeah, absolutely. I think there has been a very interesting shift over the decades, because artists, such as Brad and artists in the ’60s, they had to write their own code. They invented languages. There were no tools to do this. And many of the younger artists have switched to using tools.

And creativity resides in all different kinds of practices. You can also create very sophisticated beautiful work using commercial tools, and break them, and tweak them, and push them to limits. My experience as a curator is that sometimes I ask younger artists, oh, how exactly was that written? How does that AI respond? And they’re– I don’t actually know.

So that was a very new thing to me, because someone like Brad would go on an hour-long detailed explanation of what’s happening here, which I find fascinating. It’s a very different practice.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Joan, I’m wondering how you view the computers that you work with. Are they tools, are they partners? What’s your relationship?

JOAN TRUCKENBROD: Yes. One thing I’d like to add to the previous discussion is this idea of subverting the media, making it do what you want to do. Because the artist comes up with an idea, and digital media is really malleable and can take many different forms. So artists today, the computer has a new sense, a new ability, to reach out into the world in an interesting way using all kinds of sensors that can make work interactive.

I have a friend using a 3D printer for ceramics. I’ve done a public art installation, where I created the work on the computer, and then it was laser cut, both in steel and then an eco resin. So for me, the computer needs to be pretty much invisible in the work, because it’s not relevant to me. It’s what I can do with that, what I can make it do, and what I can create with it, which is what is important to me.

So I don’t even think the computer is a partner, even though I’ve said that previously. It’s a vehicle for me in the creative process, and it sort of undulates, I suppose, in and out. But I prefer for the computer not to be visible in the final work.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Christiane, we just have a few seconds left, and I wish we could talk more. What do you think the future of this is as technology changes?

CHRISTIANE PAUL: Well, I think in the future we’re going to see a lot more work related to artificial intelligence and machine learning, because that’s an area that is really exploding right now and artists are very interested in exploring that. And also, virtual and augmented reality. We’re in the third wave of VR and I think artists are doing very interesting things with that right now.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Christiane Paul, adjunct curator of digital art at the Whitney Museum of Art. W. Bradford Paley, a digital artist and programmer. Joan Truckenbrod, digital artist in Corvallis.

Thank you all so much for being part of this conversation. And if you want to see images or find out more, go to our website. It’s ScienceFriday.com/digital. Thank you, folks.

Copyright © 2019 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Christie Taylor was a producer for Science Friday. Her days involved diligent research, too many phone calls for an introvert, and asking scientists if they have any audio of that narwhal heartbeat.

John Dankosky works with the radio team to create our weekly show, and is helping to build our State of Science Reporting Network. He’s also been a long-time guest host on Science Friday. He and his wife have three cats, thousands of bees, and a yoga studio in the sleepy Northwest hills of Connecticut.