Understanding Plant Evolution Through Art

16:57 minutes

To understand variation in living things, scientists often compare specimens, recording the details. This kind of scientific investigation has long been practiced: Charles Darwin, for example, made sketches of everything from finch beaks to barnacles shells in his field notebooks. Today, natural history museums store these catalogues in shelves and drawers of preserved specimens.

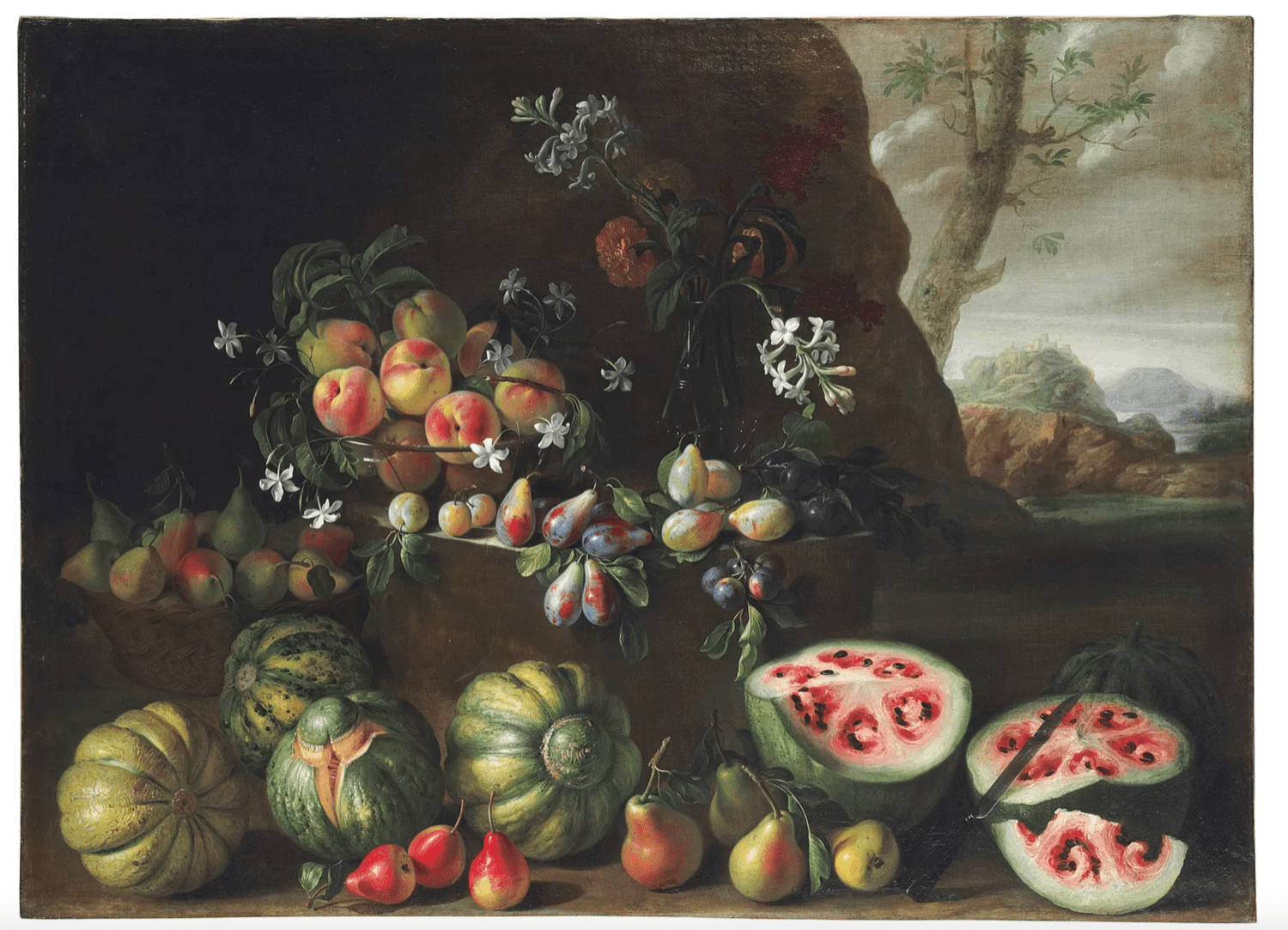

But scientists can also draw from less likely forums. Recently, one team of researchers—an art historian and a plant biologist— documented the different plant species represented in historical paintings and sculptures. Their results were published in the journal Trends in Plant Science. Plant biologist Ive de Smet and art historian David Vergauwen discuss what a 17th century painting by Giovanni Stanchi can reveal about watermelon evolution, as well as other trends in strawberries, potatoes, and other plants spotted in works of art.

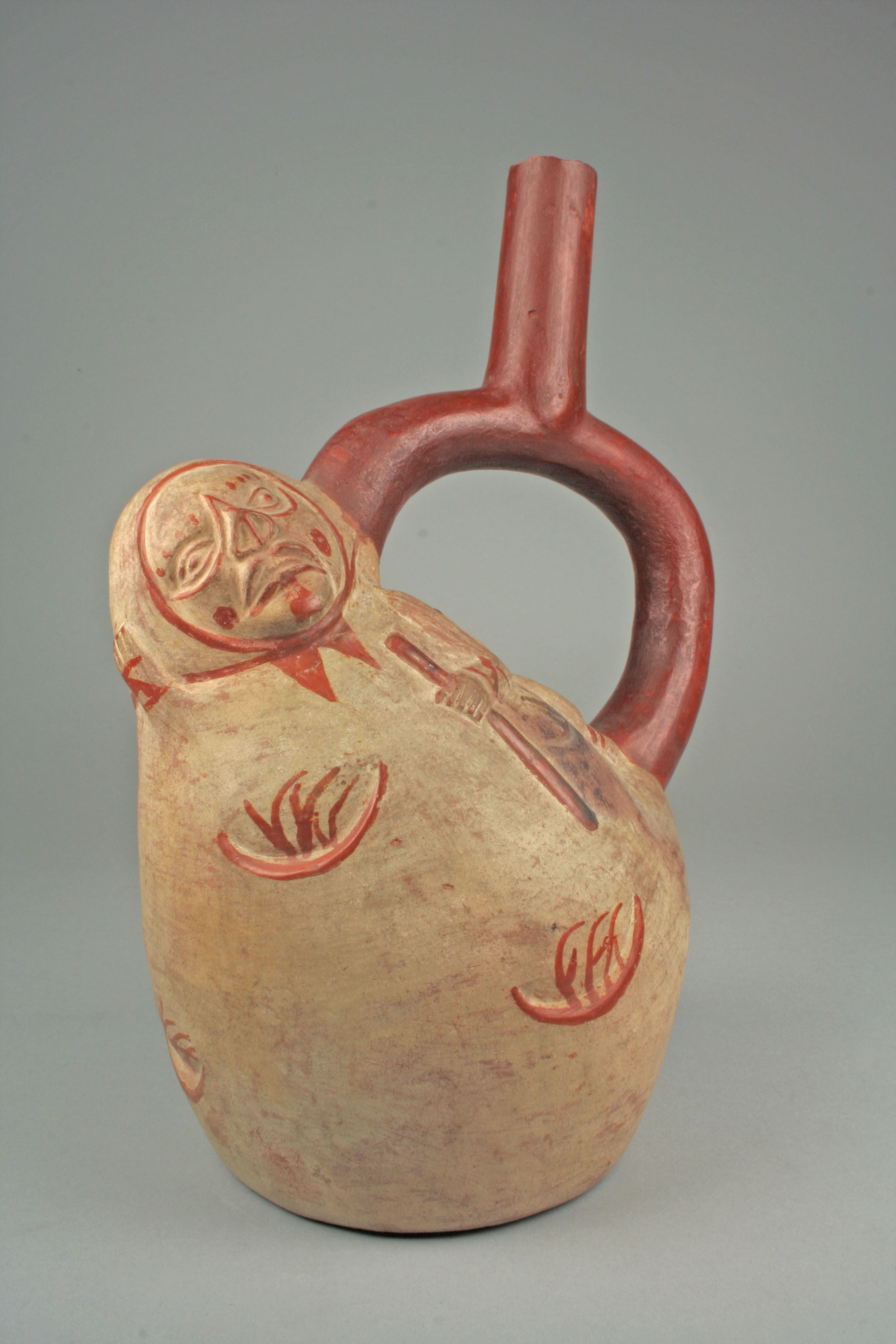

There aren’t many clues to what the diet of Moche people of South American consisted of. This large potato-shaped jug gives scientists and historians a clue to what they ate.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Ive de Smet is a plant biologist at VIB Ghent University’s Center for Plant Systems Biology in Belgium.

David Vergauwen is a lecturer of cultural history in Belgium.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. You know, in science, if you want to understand variations in living things, you take a close look at them and you catalog the details of what you see. For example, in his field notebooks, Charles Darwin made sketches of everything from finch beaks to barnacle shells. Natural history museums catalog shelves and drawers of preserved specimens.

And now there is even one team of researchers looking at works of art. They’re looking how different plant species are represented in paintings and sculptures. Producer Alexa Lim has more.

ALEXA LIM: When you visit a museum, you’ve probably run across a still life painting. Usually the image is filled with commonplace objects. Maybe a vase with a bouquet of flowers, or cups overturned with fruits cascading across the table. And when you step in for a closer look, you might think to yourself, is that a strange looking apple? Or maybe it’s an orange?

Well, you’re not alone. A plant biologist and an art historian have teamed up to catalog the fruits and vegetables in works of art. They’re looking at details in these paintings and sculptures as a way to figure out the evolutionary history of some of these plants. Their results were published in the journal Trends in Plant Science.

Ive De Smet is a plant biologist at VIB-UGent University’s Center for Plant Systems Biology. And David Vergauwen is a lecturer in cultural history at Amarant. They’re both authors on that study and joining from Gent, Belgium. Welcome.

IVE DE SMET: Happy to be here. Thank you.

ALEXA LIM: So Ive, as a plant biologist, you use genetics to study plant development. You have a lot of technical scientific tools. So why look in art? What can that fill in that maybe microbiology can’t?

IVE DE SMET: Well, in the way, because it’s fun, this is kind of an out of hand hobby project between David and myself. And what we’ve tried to do with the kind of molecular component here is we are really trying to explain why certain differences are what they are. So what we observe on a painting, certain phenotypes, certain features of color, shape, size, and these kind of things, can we find some molecular explanation for those components?

And with all the knowledge we have nowadays on how plants grow, the kind of metabolic pathways that are involved in generating color and taste and these kinds of things. So we know that key individual players for that. We can actually try to use that information to really find a good explanation.

ALEXA LIM: And David, on your end, artists aren’t always making exact representations of what they’re seeing. So how do you weed out the information from what I’m going to call the artistic license?

DAVID VERGAUWEN: Well, that is a fundamental problem when tackling this sort of research. Artists can be quite fanciful. And it is the job, or my job as an artist [INAUDIBLE] to make sure that the information that we collect from these paintings, these objects of art, that they are in some way representational for our study. So that means finding out or finding a method to really know what is reliable and what is not.

For example, if you look at a painting from 16th or 17th century Dutch painters or Flemish painters, how can you really know that in a market scene the fruit and vegetables that are depicted are really as they were at the time? Because some of these combinations seem quite odd, because they don’t grow in the same season and probably weren’t put up for sale at the same time.

So what we then do is we look at other things. So you can look at the clothes people are wearing, or you can look at the architecture, if there is architecture on a painting. And you can visit that actual place and the architecture is still there. And you can cross-reference the existing place with the painting.

Or you can look at musical instruments as they are on the painting. And you can go to the museum and check out those musical instruments. And that is the way how we can double check and cross check the validity of the things that we are observing on a painting.

ALEXA LIM: And this whole project was kicked off by a painting of a melon. Can you tell me how that happened?

DAVID VERGAUWEN: That is a funny anecdote. We’ve been friends for like way back. And every once in a while, we get the permission of our wives to go and visit the city that they don’t want to visit. And we found ourselves in Russia in St. Petersburg at the Hermitage with a painting by Frans Snyders, a Flemish painter from the 17th century.

We were discussing whether or not the melon that was depicted on that painting was, in fact, the way it used to look. So I asked Ive, is this the way a melon looked in the 17th century? And he said, well, maybe it’s just a bad painter. And then I said, no, no. This is Frans Snyders. He’s a really good painter. He’s very reliable in that case.

So then we kind of started to take out our mobile phones and look for references and colors and articles that might have some sort of indication of what was going on. And we quickly discovered that there were not that many people who were interested in cross referencing art history with genetics. And that’s how we started talking.

IVE DE SMET: Basically what was shown was a watermelon cut in half. And it was white on the inside. Which is a bit unusual, because if you think of a watermelon, everybody recognizes the outside as having this dark green spiky patterns, so alternating dark and pale green. And on the inside if you cut it in half, it’s really dark red. So the one that was depicted there was white.

ALEXA LIM: Are you confident to say this is a watermelon?

IVE DE SMET: There are a number of possibilities there. And also there are other examples. So there is a nice example from an Italian painter, Stanchi, who also paints strange looking watermelon when cut in half, so it’s a bit more white pinkish, with this kind of weird swirls on the inside. And then of course, you can discuss is this now a watermelon that was not fully matured? Is this a watermelon that was grown in conditions where it was deprived of, for example, water, or nutrients or something like that? Or is this really a mature watermelon as it existed?

And there are a number of botanical elements that you can consider for that. So if you look at the ripening process of the watermelon, it indeed starts off as being white. And then it kind of goes through these stages of turning pink, until it finally becomes really red. And when it’s becoming red, the seeds, the mature seeds are black in color. So you really know dark red together with black colored seeds is a mature watermelon.

If you go and look at an immature stage, then you see that it’s either white or pink, and then the seeds are whitish in color. So then it’s not fully developed. The way both Stanchi and Snyders depicted this essentially watermelon, which is white or pale pinkish in color, but with black seeds, really indicating that it is probably a mature watermelon.

Which doesn’t mean that at the time the red fleshed watermelon did not exist. So probably both varieties coexisted at some point. Because if you look into this genetic evidence of this watermelon from 3,500 years ago from old Egypt, we do see that at the time the red fleshed watermelon probably already existed. So the sweet tasting red fleshed watermelon occurred already 3,500 years ago.

ALEXA LIM: You’ve also looked outside of Europe. And one example is the potato. What’s the story behind that?

DAVID VERGAUWEN: Well, the story about the potato is extremely interesting, because the potato was a crop originated from South America, of course, which sustained civilizations like the Moche, for whom this potato was very important. And it figures quite predominantly in their pottery, which has a lot of these small characters, kind of humanoid looking. And they are made out of potatoes, because you can actually see the eyes of the potato that are molded into the sculpture.

And then you can find this kind of pottery not only with the Moche, but also all the way down to the urpu style Inca pottery. And then it goes to show how important it was as a color resource for these civilizations. And it is probably also related with the downfall of the Moche by the hand of their more powerful neighbors, the Tiwanaku, who once they conquered the region around Lake Titicaca, really controlled the potato trade at that time.

But the interesting bit to note is that even though the potato was quite known in Europe in the 16th century, it wasn’t really eaten in any significant amount. Wasn’t really adopted in any culinary practice before the middle of the 18th century. So there is kind of a time lag between the discovery of this potato and the actual adoption in the kitchen.

And this is quite astonishing, since for example, the Inca, they had stability of food sources, not only with the potato, but also with maize, the corn coming in from Mexico. So they have two resources that are quite efficient. Whilst in Europe, we only had the wheat. So we only had one resource, which– and the introduction of the potato really introduced some sort of food stability.

And I guess what I’m trying to say is that this story about looking at paintings and finding out the genetics and telling the story of the evolution and the travels, really involves the story of the rise and fall of civilization, of exploration, of cultural adoption, culinary practices, and so on. So it is really the story about how human kind molded its food into its own needs.

IVE DE SMET: There are often a number of misconceptions there. So typically the potato was feared, in a way, because it’s a member of the nightshade family, the Solanaceae. And then members of this family are typically poisonous. So that’s why people didn’t really like to eat those types of fruits and vegetables. So they have the potato. The tomato has a similar association. It’s kind of this guilt by association. That kind of goes that these fruits and vegetables were not really popular at the time.

ALEXA LIM: So is there like a different representation of the potato in Europe then? Or do you know when it first, like the first image of a potato happened?

IVE DE SMET: The first really kind of depicted potato kind of associated with the time that it arrived in Europe, we haven’t spotted that one yet. So I think if we have a few examples we have mentioned in the literature. This is one of the things that we still would like to explore in a little bit more detail. So when do we start? So how often is the potato depicted? So we don’t have a very good biography of that.

DAVID VERGAUWEN: We do have it with the tomato. And that’s also interesting, because you were just explaining that they were guilt by association and a bit feared at the time for various reasons. The interesting bit is that when the tomato is introduced in southern Spain, it takes about 70 or 80 years before it appears on a painting by, I believe it is Moreau, who has this famous kitchen scene, and actually depicts a tomato.

And then you can look into the past to see what it was shaped like. And it was a red kind of Coeur de Boeuf style tomato, and these things are quite valuable, because then you can have descriptions, or you can have botanical drawings. But if you can see it with full shapes and colors just lying around an early 17th century kitchen, that’s really spectacular. So if we could find something like that with a potato on there, then we’d be very happy.

ALEXA LIM: Wow. A potato mystery. [LAUGHTER] Are there plants that seem to be painted or represented consistently?

IVE DE SMET: As far as we’ve noticed, I think the onion is one example where we see very little variation. Also with respect to, I think, apples and things like that, cherries, grapes. You have a lot of diversity, but that’s clearly captures. You can really see this kind of enormous diversity of apples. But it always looked like an apple. So it’s not kind of an unusual depiction that we spotted or something like that. Same with grapes. That’s also something. And onions are the same. They’re always recognizable as an onion, as far as we’ve seen so far.

ALEXA LIM: So are we talking about the bulb of an onion, or stalk?

DAVID VERGAUWEN: No, it’s the bulb. Yeah, the bulb of an onion. OK, yeah. Not the stalk. It’s really that bulbous part of the onion that–

ALEXA LIM: You all are focusing on fruits and vegetables, but plants in general. I mean, how else could this be applied?

IVE DE SMET: We’re not going to do this for cattle. We’re not going to do this or regular flowers and things like that. So we really kind of try to define a niche, although it can be applied to all these other things as well. I mean, you can also look at butterflies and lichens, and basically conclude or draw conclusions with respect to pollution at the time.

But really kind of try to define our niche around plant-based foods, essentially. But that’s the nice thing. I mean, these painters are able to paint something with kind of photographic quality. So you can really rely on a lot of these artists to draw conclusions based on what they depicted.

ALEXA LIM: I’m Alexa Lim, and this is Science Friday from WNYC studios. David, did you ever think you’d be critically looking at apples and pears?

DAVID VERGAUWEN: Not in my life. So I was kind of dragged into it. Because it might be surprising to know that I am not really that into biology. I’ve always wondered why Ive went off to study biology. But it’s brought us a bit more together as friends, I think. And working together has been tremendously big fun. So I have learned a lot, and more than I have ever thought about genetics and plants and fruits. And you can’t imagine.

IVE DE SMET: There is some miscommunication of certain species’ names and things like that that David refuses to pronounce or to name correctly. And I’m terrible with years. I mean, I don’t know when a certain painter lived and worked and these kid of things.

ALEXA LIM: I guess on that note, you’re asking for help from people. So what do you want them to do?

DAVID VERGAUWEN: Well, we can’t be at all museums at the same time. We cannot visit– I mean, there’s not enough time for us to look at physically every painting that might be interesting. So we are just asking the public to help us, to assist us in a very simple way.

If you are in a museum, and hopefully a museum that is not that well visited, maybe obscure collections, or it can be a big museum where there is just one detail that you’re focusing on. Well, take a picture. Take a picture of the fruit or the vegetable that you find interesting, a weirdly shaped carrot, or an odd looking onion. We are interested. Take a picture of the detail, take a picture of the painting, and please don’t forget to take a picture of the little sign next to the painting, indicating what it is that we are looking at.

IVE DE SMET: It might be even more spectacular in a way way if we find a potato from on a 13th century European painting. That might completely change our view on trading routes conquest and discovery. So these things could be really interesting. And the important bit is is that when we have taken these pictures and collected all this information, you can just email it to us to ArtGenetics David Ive at gmail.com. And then we try to do something with that. And we also have the ArtGenetics hashtag. Yes.

ALEXA LIM: Thanks so much for joining us.

IVE DE SMET: You’re Welcome. Cheers.

ALEXA LIM: Ive De Smet is a plant biologist at VIB Ghent University’s Center for Plant Systems Biology. And David Vergauwen is an art historian at Amarant in Ghent, Belgium. And if you want to help with their catalog, you can tweet your photo out with the hashtag #ArtGenetics. And you can see images of the works of art up on our website at ScienceFriday.com. For Science Friday, I’m Alexa Lim.

IRA FLATOW: After the break, the world is getting louder. Has your hearing suffered? We’ll talk about hidden hearing loss, what’s next in hearing assistance technology, and why prevention is still your best cure. So coming up after the break, stay with us. We’ll be right back.

Copyright © 2020 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Alexa Lim was a senior producer for Science Friday. Her favorite stories involve space, sound, and strange animal discoveries.