Hacking The Vote: How Can We Secure Our Voting Systems?

11:46 minutes

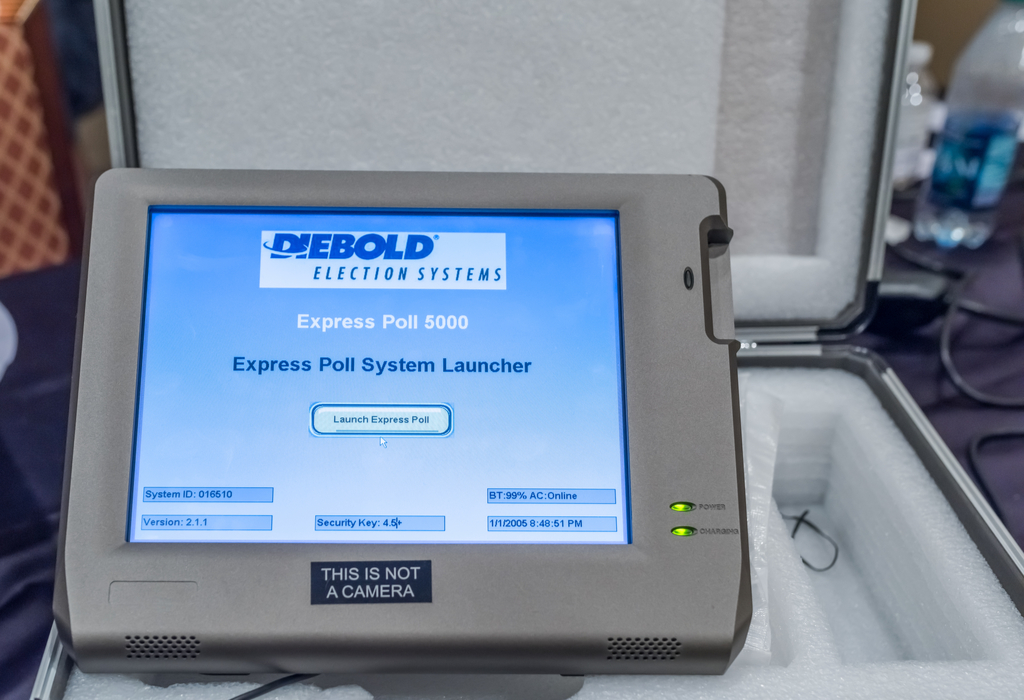

This past weekend at the DEF CON security conference, organizers set up a hacking expo to test the security of the voting machines. And this June, hackers were able to break into and take over the three dozen machines. Over 100 cybersecurity and voting experts signed and sent a letter to Congress with suggestions on protecting the U.S. voting system.

[How secure are U.S. voting systems?]

Joseph Lorenzo Hall, chief technologist at the Center for Democracy & Technology, and Edward Felten, professor of computer science and public affairs and director of the Center for Information Technology Policy at Princeton University, discuss the technological vulnerabilities and how we can secure our voting systems.

Joseph Lorenzo Hall is the Chief Technologist at the Center for Democracy & Technology in Washington, D.C.

Edward Felten is a professor of Computer Science and Public Affairs and the director of the Center for Information Technology Policy at Princeton University. He’s based in Princeton, New Jersey.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I am Ira Flatow. A bit later in the hour, a look at some promising new research, using CRISPR gene editing, to fix mutations in human embryos. Important stuff.

But first, after this past election, there’s been a lot of chatter about hacking the voting system. This June, a leaked National Security Agency report described efforts by the Russian military intelligence to launch a cyber attack to interfere with the US elections, targeting voter registration and local election officials. And this weekend, organizers of the DEF CON security conference wanted to test how voting machines could be hacked. The results– it took just 90 minutes for the hackers to get into the machines.

So can we secure our voting machines and databases? That’s what we’ll be talking about. Our number, 844-724-8255. You can also tweet us, @scifri.

Let me introduce my guests. Edward Felten is a professor of computer science and public affairs, and director of the Center for Information Technology Policy, at Princeton University. Joseph Lorenzo Hall is chief technologist at the Center for Democracy and Technology, in Washington, DC. Welcome to Science Friday.

JOSEPH LORENZO HALL: Thanks.

EDWARD FELTEN: Thank you.

IRA FLATOW: You’re welcome. Let me give out our number. It’s 844-724-8255, again, or you can tweet us, @scifri. Joe, you were at DEF CON this weekend. Tell us about– give us an example of how these hackers were able to get into these machines so quickly.

JOSEPH LORENZO HALL: Yeah, so the specific example– you had mentioned that the one machine was hacked into in about 90 minutes. Actually, the thing that took so long to do that was that that individual actually had to leave the facility and go buy a USB keyboard and come back. And so when he came back, there were two open USB ports on the back of this machine, which is completely decertified, this AVS WINVote.

And he did the three-fingered salute, the Windows control-alt-delete, and it dropped to Task Manager. And then he could load whatever he wanted. And they installed Winamp, and played the now-famous Rick Astley song, the “Never Gonna Give You Up” song.

IRA FLATOW: Are any of these machines– the kinds that he hacked– still being used at any election sites?

JOSEPH LORENZO HALL: So some of these machines are still in use, but for the most part, these were purchased on eBay or GovDeals, which is the government version of eBay. And so, in many cases, they are two or three years old, so they’re not going to be running the most current software, for example. So we did not have the actual examples of voting machines used today. These are sort of the ones that we can get from surplus, basically.

IRA FLATOW: Well, if you buy them on eBay, do they still have the software, the voting stuff, on it?

JOSEPH LORENZO HALL: Well, they do. And so, for example, that was one of the things that this group of hackers was really interested in. Can you– to what extent is the software protected? How can you get it off? Can you examine it? In one case, something that wasn’t a voting machine– a voter registration device– actually still contained a bunch of voter records that was problematic, and we weren’t expecting that.

IRA FLATOW: Hm. Ed Felten, you’ve tested voting machines yourself. You were able to put a virus on a voting machine. Did this surprise you, at all?

EDWARD FELTEN: It did surprise us, a little bit, at the time. We didn’t realize, when we first started studying these machines about 12 years ago, how vulnerable they would turn out to be. But over the years, Joe, and Joe’s group, and my group, and others, have done a lot of research on the electronic voting machines. And in every case, we have found troubles and vulnerabilities.

IRA FLATOW: How easy is it to go into a voting booth that has a voting machine– and it’s basically a computer, right– the voting machine– and take a thumb drive and stick it into the USB port, and do something?

EDWARD FELTEN: It is a computer. It is a computer. And so, typically, all of the usual ways of installing software on computers will work. If you’re in a polling place and people are looking at you, they might look at you strangely, if you were to stick a USB keyboard into a voting machine, or something like that.

But there are ways to get access, physical access, hands on, to voting machines in other settings. And in every case we’ve seen, if you can get your hands on a machine, then you can change what it does. I have a machine in a lounge area outside my office, here at Princeton, which some students reprogrammed into a Pac-Man machine.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. So you’re saying it’s possible. But is it– it’s not practical to do something to the voting machines, in reality, as they’re being used?

EDWARD FELTEN: Well, I wouldn’t go that far. To attack a voting machine, on Election Day, in the voting booth, would be more difficult, because there are eyes on that room. But voting machines are stored in warehouses every other day of the year, and just like with other computers, there are indirect ways of getting to them, by creating viruses or other sorts of malware that will spread onto the voting machines. And that’s probably a bigger threat, in practice.

IRA FLATOW: Joe, my smartphone has two-factor authentication on it. Can we put some sort of that encryption on these voting machines?

JOSEPH LORENZO HALL: So, many of these machines are 10, to 15, to 20 years old. And so to the extent that we ask of them to do, sort of, very modern– or at least, in the last two years– kinds of security operations like you’re seeing– two-factor, for example. That’s asking a bit much.

And so, often, what we have to do is sort of look to other things. So for example, processes, chain of custody– human types of things that election officials actually spend a lot of time thinking about. But you can imagine, there’s so much variation that it just depends– on where you are, what the machine is, and how vigilant that particular operation is.

IRA FLATOW: Much of the software in many of the machines is proprietary to the company that actually makes and distributes the voting machines. I’ve been reading online that people are calling for open-source software, not proprietary software. Why would that be an advantage, Ed?

EDWARD FELTEN: Well, open-source software would eliminate one of the barriers to improving the system. And that is that it would allow independent experts or members of the public to look at the software and analyze it for potential vulnerabilities. Very early in the process of studying– in the history of studying these machines– it was difficult to get access to the software, to get hands on the machines, and so on. So that’s definitely a step in the right direction, but it’s not a solution in itself. That lets you find problems, but doesn’t necessarily fix them for you.

IRA FLATOW: Is there a solution in itself?

EDWARD FELTEN: The best way to address this is to build a system that is resilient, so that even if someone does compromise a voting machine, the overall election process is safe, because you detect the problem, and then you can recover. And that involves using a voter-verified paper record– that is, something that is written on paper, that the voter saw, that is kept in a ballot box. So when you have the combination of a paper record and an electronic record, and then you do a good post-election audit to compare the paper and electronic records, that gives you the best, and most resilient, result. That way, you’re safe, even if the machines are compromised.

JOSEPH LORENZO HALL: And that’s really where the action is, because when I was a post-doc with Ed, at Princeton, we developed a form of– a statistical recount, called a risk-limiting audit, that allows you to, essentially, do what you would have done in a recount, without counting as many ballots. And we really need to see both permanent, indelible records, like paper records, and these statistical methods, to make sure it’s right.

IRA FLATOW: But each locality uses its own system for voting. I mean, there may be so many different systems. Is there a standardized system we should come up with?

JOSEPH LORENZO HALL: Well, the NIST definitely keeps standards about systems that systems should meet, but there’s so much variation in our population, and what people are comfortable with, that election officials have sought to get very different machines. I will note that election officials are starting to build their own machines. So in Travis County, Texas, in Los Angeles County, California, they’re starting to build tanks of voting machines– just extremely secure, wonderful, cryptographic, glorious, paper record-based, auditable machines.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s see if I can get a quick call in, from Denver– from Rich, in Denver. Hi, Rich.

RICH: Hey, Ira, how you doing? Great show. Hey, you could solve this problem in one minute. And if– when I first started voting, in the [? ’80s– ?] go back to paperless ballots, everybody. It would be done tomorrow.

You know, there’s places in this country, where poor and lower-educated, especially minority, don’t have internet access. They can’t vote. They can’t get to machines. We could solve this tomorrow by going back to paperless ballots, coast-to-coast.

IRA FLATOW: All right. What do you think of that, Ed and Joe?

EDWARD FELTEN: Well, I think paper ballots are– they work, and they’re the most disaster-proof, in the sense that the system– a paper-based system– will work, no matter what happens with the electricity, or anything else. But from a security standpoint, there are advantages to having a system that uses a combination of paper and electronic. Having those redundant records– the paper record that the voter filled out or saw, I’m absolutely behind that. But then, also, say, an electronic scan of that, and then being able to compare them. That gives you the best level of security. And should the machine break down and not work, you can always fall back to a good old-fashioned paper ballot and ballot box system.

JOSEPH LORENZO HALL: Yeah, and I’ll add really quickly, that in– LA has 11 languages. You can’t put 11 languages on a single ballot and make that usable. And so, in terms of usability and accessibility, and just ease of the voting process, it’s really not a paper-ballot-or-not question.

IRA FLATOW: Is there one kind of voting interface that’s worse than the other? For example, is touchscreen worse than, maybe, a mouse? Or the paper ballot combination?

JOSEPH LORENZO HALL: There’s been studies on this, and touchscreens actually perform quite well. It tends to be things like the punch cards, that we don’t have a lot of anymore, or the– there’s one machine that actually uses an iPod-like dial, that people think is a touchscreen, and start touching it, and realize, this doesn’t work. And then they use the dial. So those are the ones that tend to be the poorer, there.

IRA FLATOW: So is the greater threat from inside the system, or outside the system, leaking in?

EDWARD FELTEN: I think it’s both. You need to be prepared against both types of problems. Historically, unfortunately, there are a lot of incidents of voting officials who have– or poll workers– who have misbehaved. Those problems can exist. They’ve historically existed. They don’t exist so much today.

But you also worry about a sort of big, high-stakes attack, coming from outside. And certainly, in last fall’s election, we were quite concerned about that occurring. Fortunately, that has not occurred yet.

JOSEPH LORENZO HALL: It also depends on what you worry about. So if we’re worried about the presidential election, that is rather difficult, because of the distribution of the different kinds of technology. But for a local election, your proverbial Tony Soprano may consider it worth his while to spend $100,000 to fix an election for a local waste management bond that might be like $5 million. And those have to be just as much in our threat models as anything else.

IRA FLATOW: Mm-hmm. Good stuff to talk about. We will continue this discussion, because it’s an evolving one.

Ed Felten, professor of computer science and public affairs, director of the Center for Information Technology and Policy at Princeton University. Joe Lorenzo Hall, chief technologist at the Center for Democracy and Technology in Washington. Thank you both for taking the time to be with us, today.

JOSEPH LORENZO HALL: Thank you. It’s really an honor, Ira.

EDWARD FELTEN: You’re welcome.

IRA FLATOW: It’s my pleasure.

Copyright © 2017 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Alexa Lim was a senior producer for Science Friday. Her favorite stories involve space, sound, and strange animal discoveries.