Scientists Can Now Hear The Background Hum Of The Universe

12:19 minutes

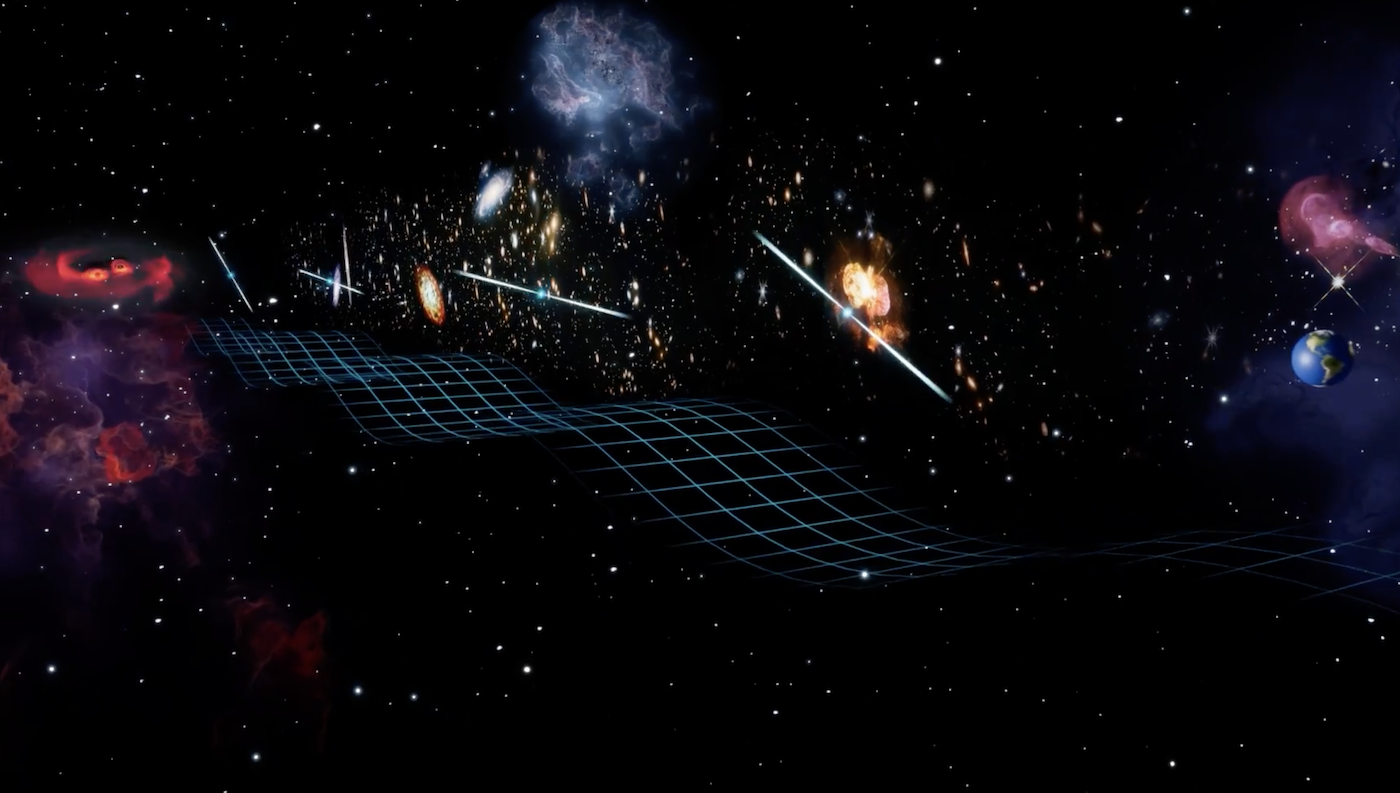

For the first time ever, scientists have heard the “low pitch hum” of gravitational waves rippling through the cosmos. It’s this ever-present background noise set off by the movement of massive objects—like colliding black holes—throughout the universe. Scientists have theorized that it’s been there all along, but we haven’t been able to hear until now. So what does this hum tell us about our universe?

SciFri producer Kathleen Davis talks with science writer Maggie Koerth about this discovery, as well as other science news of the week. They chat about the possibility of an icy planet hiding in the Milky Way, air quality problems due to wildfire smoke, an experimental weight loss drug that’s currently being tested, if our human ancestors were cannibals, and how dolphin moms use baby talk with their calves.

Maggie Koerth is a science journalist based in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: And I’m SciFri producer Kathleen Davis. Ira and I are hosting together this week.

IRA FLATOW: Later in the hour, a trip to Miami for our Cephalopod Week Cephalobration.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: But first, big space news dropped this week. For the first time ever, scientists heard the hum of gravitational waves rippling through the cosmos. It’s the kind of background noise set off by the motion of massive objects throughout the universe.

Here to talk about this cosmic news and more is Maggie Koerth, science writer, based in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Maggie, welcome back.

MAGGIE KOERTH: Hi. Thanks for having me.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: So Maggie, talk me through this big physics news.

MAGGIE KOERTH: So first off, you have to understand a little bit about what these gravitational waves are. So imagine this entire universe exists on a giant trampoline. And if somebody bounced or moved around, there’d be a movement in the fabric near you. Even if they were really far away, it might be just this very faint movement. And that’s this basic idea behind a decades-long effort to document the existence of these gravitational waves. They’re just kind of like the movement in the fabric of space time itself caused by things like black holes colliding.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: OK. So how did scientists actually figure this out?

MAGGIE KOERTH: Yeah. So what the scientists figured out this week is that they announced that they’d captured evidence that of these waves. And it’s not the first time this has happened. You might remember a big gravitational wave discovery back in 2015, for instance.

But what makes this different is that these are really massive black holes that are colliding. And they’re also much farther away. The waves, the movement in the fabric, has much longer wavelengths. Imagine the difference between a child bouncing nearby you on the trampoline and two full-grown adults bouncing on a trampoline that stretches five miles away from you.

To measure something that far and big, scientists had to develop a completely different way of going about the measurement process. And their solution was to hack the universe and turn the whole universe into a detection system.

And to do this, they studied these natural radio waves that are produced by quickly-spinning collapsed stars. We’re talking about things that are rotating several hundred times a second. And those rotations mean that the radio wave signal produced by the star goes in and out of line with Earth at regular intervals. You could call them pulses. Hence, the name “pulsars.”

So by monitoring dozens of these pulsars for more than 15 years, the scientists were able to spot the times when gravitational waves jiggled the signal between Earth and the pulsars.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: So what does this tell us about the universe? I mean, this seems like it might be pretty important in the world of physics.

MAGGIE KOERTH: Yeah. Well, first, they want more data to verify it. The scientists were very careful not to fully claim discovery this week. There’s a lot of talking around, like, oh, we found evidence that could lead to a discovery hedging. But one thing they’re hoping for is that, as they bring in more of this evidence, they might be able to figure out where the signals are coming from. Which is to say where a pair of black holes are actually colliding in space. And they could point their telescopes there. And they could see one for the very first time.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: OK. So let’s move on to more space news. There could be an icy hidden planet in our galaxy– more specifically, in the Oort cloud. But Maggie, what is that?

MAGGIE KOERTH: Besides a wonderful thing to say over and over again?

[LAUGHTER]

The Oort Cloud is a– basically, imagine a giant sphere of snowballs surrounding our entire solar system, and you’ve kind of got the idea. Only the snowballs in this case would be frozen bits and bobs of planet-making material– something that scientists call planetesimals. And they were left over from the formation of our actual solar system planets, but they got thrown away from the sun by the planets’ gravity. At least this is the theory.

The Oort Cloud is one of those things in space that is predicted to exist, but we don’t actually know for certain that it does. No one’s ever seen it. It’s so far away that Voyager 1 is going to take 300 years to reach the edge.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Wow.

MAGGIE KOERTH: Yeah. So all of that background is important because a recent simulation of the mechanics of the early solar system suggests that there’s a decent chance that it’s not just planetesimals out there in the Oort Cloud. There could be a real full-scale rogue planet floating around out there. And the simulation suggests that there’s a 0.5% chance that a planet formed in our solar system and got thrown into the Oort Cloud by the gravity of all of the other planets.

But the more cool possibility and the more likely one– there’s a 7% chance that our Oort Cloud snagged a whole planet from some other solar system.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Well, we’ll just have to use our imaginations, I guess. But let’s come back down to Earth for our next story. And Earth is having some serious climate-related air quality problems. A few weeks ago here in New York City, the air was this murky orange color. And now I’m hearing that the Midwest is getting the worst of it. I mean, what’s happening?

MAGGIE KOERTH: Yeah. I’m in Minneapolis. We had a terrible week of air quality. Chicago, on Tuesday, literally had the worst air quality in the world. And this is not the only time it’s happened in the Midwest this summer. Just a couple of weeks ago, Minneapolis had the worst air quality in the nation. And that was a day when being outside was the equivalent of smoking half a pack of cigarettes.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Wow.

MAGGIE KOERTH: We’ve just been getting hit by these repeated waves of barbecued air on a massive scale. And it’s all thanks to one of the worst forest fire years on record in Canada. As of Tuesday afternoon, there were 488 fires burning in Canada. And more than half of them were listed as out of control. Smoke had even reached all the way to Europe.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Wow. I mean, how do we keep ourselves safe?

MAGGIE KOERTH: Fire season, though, typically peaks in Canada in July and August. So you can really expect more of this to come. And what experts recommend are a range of things. The first option is to basically stay inside with the windows shut and the AC running continuously, not just on auto cycle, so that you’re filtering the air as it comes in to you.

But if you have to be outside, you should be avoiding strenuous activities like jogging or mowing the lawn on bad air quality days. And masks can also help– particularly N95 masks. They won’t filter out any like toxic gases that are in the smoke, but they will reduce the amount of those tiny particles that get into your lungs and throat and irritate things and lead to this scratchy throat situation that I am experiencing right this moment.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Well, please stay safe out there, Maggie, and everyone else who’s listening.

Now, onto some other health news. There is a new weight loss drug that is currently being tested. Maggie, can you tell us about this?

MAGGIE KOERTH: Yeah. So this is part and parcel with the weight loss drugs that you’ve really heard about in the news all this past year, Mounjaro and Ozempic. Eli Lilly released results of a phase II clinical trial this week that showed this new drug could have results that are just as good, if not better, than those. In an 11-month trial, people taking the new drug lost 24.2% of their body weight on average.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Wow.

MAGGIE KOERTH: Yeah, it’s a lot. The existing drugs– Mounjaro and Ozempic– are in the same ballpark– 15% to 20% of body weight, on average, for the same length of trial, according to an article in Nature. So what we’re talking about is really this market for pharmaceutical weight loss expanding and becoming available to more people. And that could be good, but it could also be a problem.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Yeah. So like you said, people in these trials have lost almost a quarter of their weight, on average. Is that safe?

MAGGIE KOERTH: Well, that’s one of the things that doctors are trying to figure out a little bit. The main side effects of these drugs, for the most part, have been nausea and vomiting. But doctors have expressed a lot of concern about the increasing use of these drugs by people who are not actually diabetic or obese and who aren’t being monitored for malnutrition by regular doctor visits. So these are drugs also you basically have to take indefinitely to maintain results. And they’re drugs that can, in some people, just wipe out the desire to eat much at all. And that is obviously not very healthy.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Let us move on to our next story, which I’m struggling with how to transition into this one coming from that story. But this story is about how our ancient ancestors may have been cannibals. Maggie, how did scientists figure this out?

MAGGIE KOERTH: Yeah, there’s a diet joke in there somewhere, but I don’t know what it is.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Yeah, I’m not even going to try.

[LAUGHTER]

MAGGIE KOERTH: So scientists have found a 1.45-million-year-old hominin tibia that shows signs of having been cut with stone tools. That is to say, the proto-person this shin bone belonged to was probably butchered and likely eaten by its peers. And no one knows what specific species the bone came from– just that it’s a human ancestor. And there’s other evidence that exists that hominins were at least sometimes eating each other. There’s a similarly aged skull from South Africa that has the same kind of cut marks.

But this tibia is important because it was found in a part of what’s now Kenya, where the fossil record shows no contemporaneous signs of funeral rituals. Which would be your possible alternate explanation for why hominins might be cutting the flesh off of each other’s bones.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: I want to wrap up with my favorite story of the week. A new study showed that mama dolphins use baby talk with their calves. Which is so cute. How do those calls sound different from what a mom would maybe whistle to another adult dolphin?

MAGGIE KOERTH: The scientists studied these 19 mother dolphins, who had been captured temporarily for health assessments. And basically, just like humans, when we’re talking to babies, we’re sort of getting up into that higher register and kind of having a little bit more spread of the tone also. And it doesn’t happen all the time. It’s something that we have yet to observe in wild non-human-centric dolphin behavior. But it’s really interesting and also it’s kind of cute.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: OK. So let’s take a listen. We have a clip from the Sarasota Dolphin Research Program of a dolphin without her baby.

[DOLPHIN VOCALIZING IN A LOW REGISTER]

And now we have a clip of mama dolphin with her baby. [DOLPHIN VOCALIZING IN A HIGH REGISTER]

I can tell that there’s a little bit of a difference. But what could this mom dolphin be saying? Do we know?

MAGGIE KOERTH: Well, this comes back to another really cool fact about dolphins. Which is that they kind of have names. Each dolphin has this little unique whistle that is this identifier of themselves. And they’ll go around shouting it to let other dolphins know where they are. And so what this is is the mother dolphins expressing their names to their babies, according to an article in Science News.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: So cute. Maggie Koerth is a science writer based in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Maggie, thanks so much for joining us.

MAGGIE KOERTH: Thank you so much for having me.

Copyright © 2023 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Rasha Aridi is a producer for Science Friday and the inaugural Outrider/Burroughs Wellcome Fund Fellow. She loves stories about weird critters, science adventures, and the intersection of science and history.