Scientists Create Glowing ‘RNA Lanterns’ With Bioluminescence

14:49 minutes

The inner workings of our bodies, particularly what’s happening inside our cells, can be kind of a black box—with countless tiny molecules constantly working and churning to keep us alive. A new technology that blends bioluminescence with cellular machinery may shine some light on the details of their comings and goings and interactions that can be hazy.

Scientists had the bright idea to take that same enzyme that makes fireflies glow and tie it to RNA, the molecule that reads the genetic information in DNA. This developing technology has been used on mice, with the hope that these light-up molecules can help illuminate how viruses replicate or even how memories form in the brain.

Flora Litchtman talks with Dr. Andrej Lupták, professor of pharmaceutical sciences at the University of California Irvine and Dr. Jennifer Prescher, professor of chemistry at the University of California Irvine, about their research on the topic.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Dr. Andrej Lupták is a professor of Pharmaceutical Sciences at the University of California Irvine in Irvine, California.

Dr. Jen Prescher is a professor of Chemistry at the University of California Irvine in Irvine, California.

FLORA LICHTMAN: This is Science Friday. I’m Flora Lichtman. The inner workings of our bodies and our cells can be kind of a black box. We know that all these itsy bitsy molecules are constantly working and churning to keep us alive. But the details of their comings and goings and interactions can be hazy. But a new technology that blends bioluminescence with cellular machinery may shine some light.

Scientists had this bright idea. Take that same enzyme that makes fireflies glow and tie it to RNA, the molecule that reads the genetic info in DNA. And the hope is that these light-up molecules can help illuminate how viruses replicate or even how memories form in the brain. Joining me now to tell us more about their research are my guests, Dr. Andrej Lupták, Professor of Pharmaceutical Sciences at the University of California, Irvine, and Dr. Jen Prescher, Professor of Chemistry at the University of California, Irvine. Welcome to Science Friday.

ANDREJ LUPTÁK: Hello.

JEN PRESCHER: Great to be here.

FLORA LICHTMAN: OK, Andrej, refresh our memories. Remind us quickly what RNA does.

ANDREJ LUPTÁK: Well, RNA is the first molecule that gets made as the genetic information that’s encoded in DNA is executed. And the first thing that would happen if you say, OK, go do this, go do that, on the molecular level, what you’re doing is you’re expressing an RNA. You’re making an RNA molecule. So it’s the first act of gene expression.

FLORA LICHTMAN: So I think of RNA kind of like the middle manager. Like, it takes direction from the DNA. And then it delegates to the cellular machinery that will make it happen. Is that the right analogy?

ANDREJ LUPTÁK: Yeah. Yeah, that’s a really good way to think about it. But it has its own functions in its own right. Sometimes it catalyzes chemical transformations. Sometimes it acts in regulating other cellular processes.

FLORA LICHTMAN: So you attached this little lantern to it. Is that the right way to think about it, Jen?

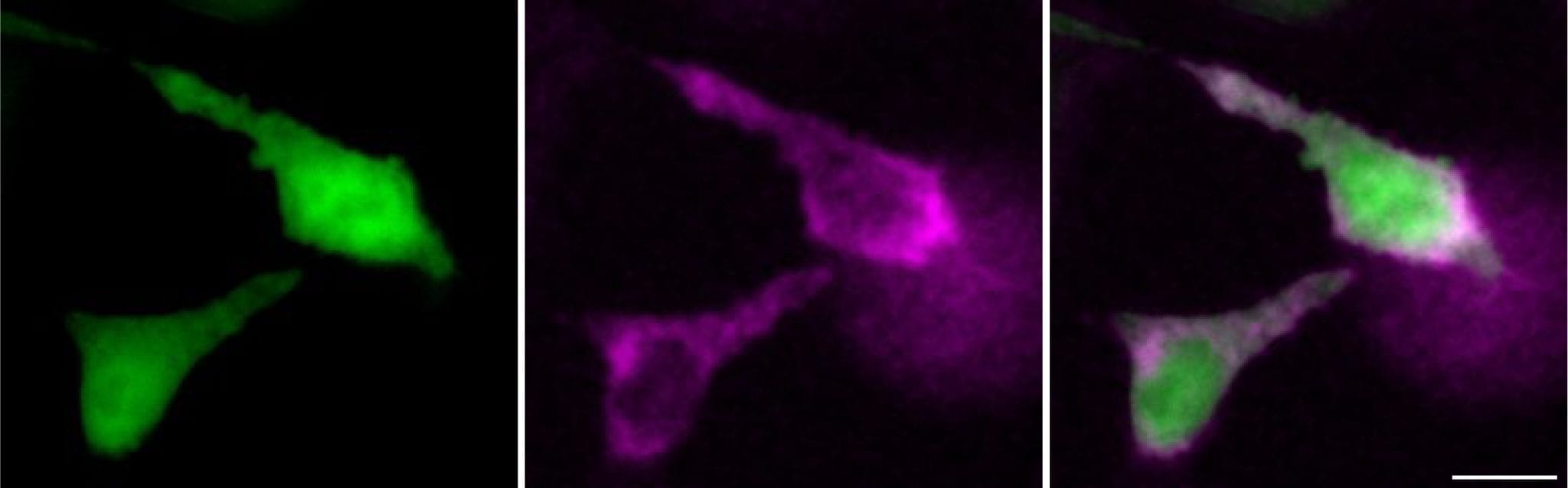

JEN PRESCHER: That’s absolutely right. We took a well-known light-emitting system in nature, these bioluminescent probes, which comes from a luciferase reaction with the luciferin small molecule. And that creates light. And we used those components and dragged them to RNAs of interest. And so when the RNA was produced, we had the light-emitting enzyme dragged to it. And we could see light production relevant to the presence of the RNA itself.

FLORA LICHTMAN: How long does that little firefly lantern stay on? Like, is it on indefinitely?

JEN PRESCHER: In the first system that we produced, we designed the lantern to stay on for the lifetime of the RNA. So whenever the RNA was present, the light would be there. And whenever it wasn’t, we would see no light.

FLORA LICHTMAN: How do you know that the lantern isn’t messing up the function of the RNA, isn’t getting in the way or mucking up what the what the RNA does?

ANDREJ LUPTÁK: The key aspect of our work was to design and then optimize a tiny, tiny, tiny RNA that is a module. And we spent a good two years making sure that it’s independent of other parts of other RNA. So it’s basically like a little solid rock that the luciferase binds. We don’t have any evidence that that part of the RNA interferes with any other function of a longer RNA that it may be part of or another RNA in the cell.

FLORA LICHTMAN: So you popped it on a place on the RNA that’s not doing anything else?

ANDREJ LUPTÁK: That’s right.

FLORA LICHTMAN: OK. And so why RNA? Why illuminate its comings and goings?

ANDREJ LUPTÁK: Scientists have been illuminating many aspects of the cell for many years. For RNAs, it’s a couple of decades behind what other areas of, particularly, studying proteins has been doing. And so it was simply a gap that we wanted to fill because we had questions about where RNA was produced, when it was produced, and where it was going. And we wanted to understand this on levels from basically single molecule all the way to living mouse.

FLORA LICHTMAN: What does this look like? What’s the readout of this? Can you help me picture it in my mind?

JEN PRESCHER: The light emission that we’re using here isn’t bright enough to see with your own eyes at this level. But we use really sensitive cameras, similar to those that are used by astronomers and so forth to collect every last little photon coming out of a given system. And those then create a snapshot of the lantern and the associated RNA at a given time.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Are you saying that we’re using sort of like telescope technology to look inside the body?

ANDREJ LUPTÁK: Absolutely. There’s different ways of thinking about how to observe things. And the telescope analogy here is a good one because we’re trying to put the largest lens we can over our experiment and then essentially tie it to a very, very sensitive camera.

FLORA LICHTMAN: What are the questions you’re excited to investigate with this new technology?

ANDREJ LUPTÁK: Oh my, that’s another part of our every week something else comes up we would like to know. In a live mouse, when a memory-forming event takes place and then RNA is expressed that is related to that memory formation.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Wait, you’re going to have to back up. A memory-forming event?

ANDREJ LUPTÁK: Well, it’s something that a mouse would remember.

FLORA LICHTMAN: How is RNA related to that? I think we think of neurons and synapses. But tell me how RNA plays a role or might play a role.

ANDREJ LUPTÁK: Well, in all events that are meant to leave a lasting effect, so that would be a memory, RNA is involved because you’re in a neuron, and RNA is made to then code for a protein that is involved in, for example, strengthening of a synapse. So ultimately, the synapse may be built out of a membrane and membrane proteins. But the information that codes for it is delivered locally via an RNA.

Neurons are particularly interesting because they’re large. They’re huge cells. It’s a long way from a nucleus to a synapse in certain neurons. And so there is a lot of questions related to transport, levels of expression. How does it find its way? When does it go there? We have answers to these questions from cell culture experiments that has been done over the past, oh, almost about three decades. But in a live organism, we have not seen that. We would really love to.

FLORA LICHTMAN: It sounds like RNA are sort of making the tiniest building blocks of memories, and this technology would allow you to sort of see those blocks being placed. Does that sound about right?

ANDREJ LUPTÁK: Yeah, that’s a good way of thinking about it. We think of it more of how the information is moved from the nucleus where the DNA is stored. And you’ve parked your car today; you want to find your car when you come back.

FLORA LICHTMAN: So could this technology be used to help us make better mRNA vaccines, for example?

ANDREJ LUPTÁK: We believe so. We think any time you have a tool, a molecular tool that lets you visualize something fundamental, a key technology where you know where you’re putting it, At what point does it enter the cell? How quickly does it enter the cell? and ideally, Which cells are affected? we can then use that as a tool to build better vaccines and deliver the mRNAs to places more precisely, for example.

FLORA LICHTMAN: What about viruses? They’re made of RNA often, right? Could you add your lantern to a virus?

JEN PRESCHER: Absolutely. The lanterns can report on RNAs from not just human cells but also those from different viruses. And we’re very much interested in being able to use the lanterns and different colors of lanterns to be able to track the spread of different viruses in models to learn more about the underlying biology and potentially then ways to treat infection.

FLORA LICHTMAN: So that would be revolutionary, right, being able to watch a virus move through the body?

JEN PRESCHER: Right, being able to watch the spread of viral infection over the whole organism would provide some novel insights into the spread of infectious disease and things that we might not even realize are happening. And that then leads to better avenues for treatment.

FLORA LICHTMAN: How long did it take to get this to work?

[LAUGHTER]

Why are you laughing?

JEN PRESCHER: This project was sort of years in the making. Andrej and I have been colleagues at UC Irvine for almost 15 years now. And these have been ideas that have been percolating, I think, over the entire 15-year period. And within the past five years or so, we really started to focus on this aspect of using luciferases to tag RNAs. Andrej is an expert in RNA biology. And I have done a lot with developing luminescence technologies over the years. And so that was sort of a natural fit.

But there were so many things that needed to be optimized to pull off these types of experiments, from designing the RNAs to designing the lantern proteins to developing the small molecules and the instrumentation and analyzing cells and whole organisms.

So we really needed a whole kind of dream team of people also to come together, including one of our close collaborators on this project, Oz Steward from the Neurobiology Department here at UC Irvine. And then we also had a really outstanding team of students that got this project off the ground. And I think without them, we couldn’t have spanned this highly interdisciplinary area to pull this off. What do you think, Andrej?

ANDREJ LUPTÁK: I agree. And the one other thing was about 9 or 10 years ago, we started writing proposals to get this funded, to get it going. And it was a struggle for a while. It took time to, both, assemble the team and find the support for it.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Well, I want to ask about that. It was a struggle because it was basic research or because people didn’t see the value or people didn’t think it was going to work? What was the struggle?

ANDREJ LUPTÁK: I think people didn’t think it would work. Well, we know that because we got the reviews.

FLORA LICHTMAN: They told you?

ANDREJ LUPTÁK: [LAUGHS]

Early on, some of the reviews we got were, well, you guys will never have enough photons to see what you think you will see. It’s challenging to convince others that are used to looking at a much stronger signal that we will see what we think we will see, and it’ll be in real time with good spatial resolution. And ultimately, that’s what ended up happening. But it took a while.

FLORA LICHTMAN: What did it feel like when it did start working?

ANDREJ LUPTÁK: Oh, it was amazing.

JEN PRESCHER: It was awesome, yeah.

[LAUGHTER]

ANDREJ LUPTÁK: In some ways, we got– I wouldn’t say lucky, but we had a hint that it was going to work right when we finally had the team assembled. When we started working on this in earnest, we had a smidget of a signal that we call the 1.2 day.

JEN PRESCHER: Yes.

ANDREJ LUPTÁK: And it was the signal– the signal over background was 1.2. So you can imagine it wasn’t much.

FLORA LICHTMAN: That’s a very scientist way of saying very little was coming through, right?

ANDREJ LUPTÁK: Very little was coming through. And we were reasonably convinced that, yes, that signal is real. And so let’s just work on it. Let’s optimize. Let’s engineer this. Let’s hit it from every angle. And that 1.2 turned into about 400 or 500, ultimately. The effort led to about 100-fold improvement.

JEN PRESCHER: Yeah, I would definitely say that every week, it seems like there’s some exciting eureka moment with the images and things that we’ve been generating. And this group gets together every Friday to go over the latest. And I think that feeling of excitement that came from the 1.2-fold measurement early on, that has sustained itself through all of these weekly meetings over the years.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Are people knocking down your door to get ahold of this, other scientists?

JEN PRESCHER: We certainly had people reach out to acquire the different sequences and the different lantern components that we’ve been using. One of the most fun things about being involved in imaging tool and technology development is to see just how far and wide it is applied and the new insights it can bring beyond the applications that we’re performing in our own lab.

FLORA LICHTMAN: What’s next for you two?

ANDREJ LUPTÁK: More photons.

FLORA LICHTMAN: More photons.

[LAUGHTER]

ANDREJ LUPTÁK: Well, we’re very, very excited about this. And some of the experiments that we described, including with RNA viruses, with mRNA delivery and, in particular, in neurobiology, in neurons, those are the key areas that we’re working on.

FLORA LICHTMAN: When do you think we’re going to start seeing new discoveries using this tech? Like, when do you expect we might learn more about how memories are formed or start tracing viruses in the body?

ANDREJ LUPTÁK: Well, I think the viral work can be quite quick. It’s really just putting these tools into the viral RNA and then doing fairly standard virology experiments. So it depends on how well it works, but that should be months. The questions related to neurobiology tend to be slower. I think we’re looking at a couple of years.

FLORA LICHTMAN: The brain is a complicated place.

ANDREJ LUPTÁK: Sure.

JEN PRESCHER: Yes, indeed.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Thank you so much for joining us today.

JEN PRESCHER: Thanks for having us.

ANDREJ LUPTÁK: Our pleasure. Thank you.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Dr. Andrej Lupták, Professor of Pharmaceutical Sciences at the University of California, Irvine. And Dr. Jen Prescher, Professor of Chemistry at the University of California, Irvine.

Copyright © 2025 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Shoshannah Buxbaum is a producer for Science Friday. She’s particularly drawn to stories about health, psychology, and the environment. She’s a proud New Jersey native and will happily share her opinions on why the state is deserving of a little more love.

Flora Lichtman is a host of Science Friday. In a previous life, she lived on a research ship where apertivi were served on the top deck, hoisted there via pulley by the ship’s chef.