Mapping Migration In Asia Through Ancient Genomes

16:42 minutes

The history of a group of people can be reconstructed through what they’ve left behind, whether that’s artifacts like pottery, written texts, or even pieces of their genome — found in ancient bones or living descendents.

Scientists are now collecting genetic samples to expand the database of ancient East Asian genomes. One group examined 26 ancient genomes that provide clues into how people spread across Asia 10,000 years ago, and their results were published this month in the journal Science.

Biologist Melinda Yang, an author on the study, explains how two particular groups dominated East Asia during the Neolithic Age, and how farming may have influenced their dispersal over the continent.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Melinda Yang is an assistant professor of Biology at the University of Richmond in Richmond, Virginia.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. The human family tree is complicated, like most families. The road map of how our ancient ancestors journeyed out of Africa and across the globe is filled with twists and turns, dead ends, and missing pieces. One of those missing pieces is how early humans populated East Asia. Scientists are using ancient genomes to fill in that story. And Producer Alexa Lim has more.

ALEX LIM: The history of a group of people can be reconstructed through what they’ve left behind. That can be artifacts like pottery, written text, or even pieces of their own DNA, found in ancient bones and in their living descendants. A group of scientists examined 26 ancient genomes from East Asia that give clues to how people spread through that continent 10,000 years ago.

The results were published this month in the journal Science. Melinda Yang is one of the authors on that study. She’s a professor of biology at the University of Richmond in Virginia. Welcome to Science Friday.

MELINDA YANG: Hi. Thanks for having me.

ALEX LIM: So you looked at the genomes of East Asians who lived during the Neolithic age, which is around 10,000 years ago. Can you describe that era? Humans were living in communities then? What were they like?

MELINDA YANG: I would say that the Neolithic age started around 10,000 years ago. That was like the Early Neolithic. And then that lasted until about 4,000 to 3,000 years ago, when you start transitioning into the Bronze Age. And so this period is largely defined by the development of farming, and associated with farming, very settled communities that start across this time period, changing in complexity.

So at the very beginning, 10,000 years ago, there’s still a lot of questions about, oh, there’s a little bit of evidence of farming, but there’s a lot of things that show it’s not their major mode of economy. And then by the Late Neolithic, you start getting very established, complicated settlements that sometimes show levels of hierarchy. There may be walls that are around these settlements. There may things that look like prestige items that sort of suggest that there’s perhaps some inequalities amongst the people that live within that community.

ALEX LIM: So like I mentioned, you collected these samples of ancient genomes. What was the main question you were trying to answer in your study?

MELINDA YANG: So we had individuals from Northern China, sort of along the lower edges of the Yellow River, the main river in Northern China. And then we had individuals from Southern China, who were along the southern coast, near the Taiwan Strait. So basically, with these two, we sort of have samples from the two major regions of China.

But because we have these samples, we could start asking, OK, what are the differences between these two groups? There’s not really a clear difference between these two groups today, if you look at their genomes of present-day populations. And it’s a, what was it like at this point in the Early Neolithic? Are there changes that we can observe that are tied to this time period?

But I think the first thing is, we just had no samples from this area, and it’s a major archaeological region. There’s major transitions that are happening through this time period. So we wanted to be like, what is it that’s happening in Mainland China?

ALEX LIM: Right. Whenever we talk about genetic splits in populations, it gets complicated keeping track. It’s like trying to keep track of all the characters in Game of Thrones, right?

[LAUGHTER]

So then, what you’re saying is, there were these two genetically distinct northern and southern groups. And then they kind of mixed? Is that what happened?

MELINDA YANG: That’s one of the first big findings that we saw, is that, when we look at these past populations, perhaps really starting from the Early Neolithic– so that’s about 9,500 to 8,000 years ago are the samples that we have from then. And then we have it from both sides. And when we looked at them and we compared them to each other, we found that they were very genetically distinct from each other, in a way that present-day populations from those two areas were not. So that was our first big thing of like, oh, here we can find this differentiation from each other that is very hard to discern if you just use modern human genomes from the same regions today.

Then after that, the very fact that we see that difference between back then and today sort of was this marker of like, hey, admixture is likely the big thing, where some intermixing between these populations is likely the big thing that made it so that today’s populations don’t have this level of differentiation.

ALEX LIM: And when you say admixtures, that means they’re having kids with each other, right?

MELINDA YANG: Yeah. So admixture is a technical term. Sorry. So basically, when they’re having kids with each other, if you’re from two very distinct groups of people genetically, then you can sort of see that mixing in the genome. Because you get one from your mom, one from your dad, in terms of your chromosomes, each of your chromosomes. And so then therefore, if there’s really different patterns, say your mom comes from a population that has a mutation A, and then your dad comes from a population that has mutation B, you’re going to have a mix of those.

And then if you’re looking at it in a population level, you’re looking at sort of like frequencies of these mutations. And if you have ones that show up that you don’t typically find, it’s more likely that it came from an outside population than that it was a new and separate mutation that happened at the exact same spot. That’s really statistically unlikely.

ALEX LIM: Right. And so then, why did the northern population start moving down or why did it start becoming more dominant?

MELINDA YANG: So here, I’m going to say it’s a bit more speculation. But what we need is, I think, more samples from these areas. But because of the fact that we see this occurring in– like in the Early Neolithic, you don’t really see this mixing, but then you do see it by the Late Neolithic within those southern populations. And then you do see most of that northern ancestry today, the combination of that and previous archaeological studies that have shown that there is this expansion of farming that sort of comes out from the Yellow River region, which became a major farming area by the Late Neolithic.

And so this area, these people were likely moving southward and carrying some of their farming technology with them. And so therefore, you see a later spread of farming technology in certain areas of the south. And so therefore, you sort of have this overall story of a north to south wave that’s occurring across many different regions. And when we’re studying this, we’re seeing it over and over again in different places, so that’s really neat.

ALEX LIM: So then where did the southern group go?

MELINDA YANG: One of our other major findings here is, the big thing here is we don’t have samples from more inland southern China. So who knows what on the other side and what types of ancestries are there. But at least these people that we do have from coastal Mainland China, what we found is that they show a really close relationship to present-day Austronesians. And so Austronesian refers to sort of a language family that’s found in Taiwan, in islands of Southeast Asia and islands of the Southwest Pacific. But what’s really cool is that these ancient southern East Asians, they show a really close relationship to these Austronesians.

What I mentioned is that the southern ancestry sort of still exists a little bit in humans today, so they clearly mixed with the northern populations that were coming down. And so they still persist in Mainland China. But then, these peoples also moved into Taiwan and then into the rest of Southeast Asia and the Pacific Southwest. I guess, in a way, you could say that they have like the living remnants. And so that’s where they still exist, sort of in the most clear genetic ancestry of them.

ALEX LIM: Right, OK. So I want to take a step even further back. One of the earliest modern human scientists found in East Asia dates back to 40,000 years ago. Who was that person?

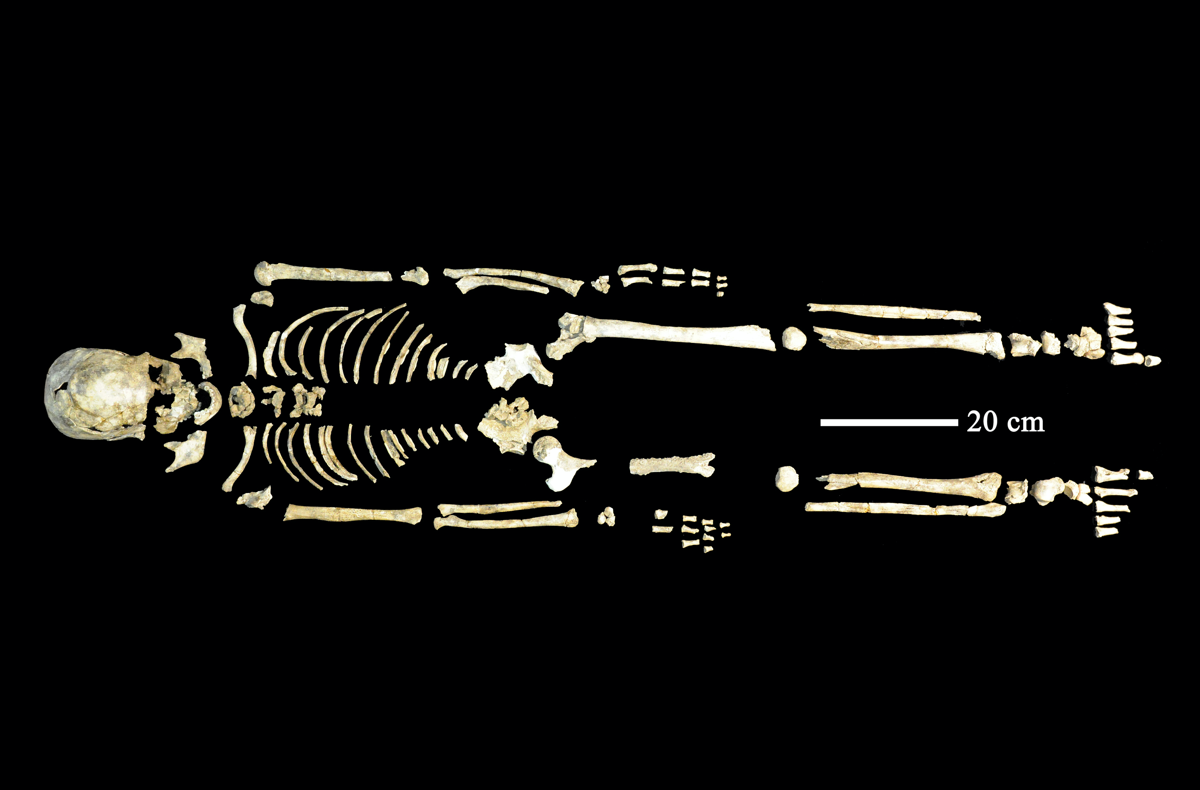

MELINDA YANG: Yeah, so that was the Tianyuan man. He is an individual that was found at a really important site for paleoanthropology that’s right in Western Beijing. But he’s 40,000 years old. And so he’s very clearly mostly related to modern humans, very clearly a Homo sapiens. The big finding that we had with him was that this is, essentially, an early Asian. So it’s not very closely related to East Asians, but it’s closest to them relative to Europeans, for instance.

And so we have sort of something that you could call Asian-like in terms of their genetics, 40,000 years ago in this area. But it’s also the ancestor to all the Southeast Asians. It’s also ancestor to Native Americans before they crossed the Bering Strait. So you have a very old Asian ancestry, is what I’d call it. There’s more recent stuff from other studies that show that there’s other ancestries that are also super old and diverged and separate from present-day East Asians that we find more recently that are in Southeast Asia.

There’s something that exists in Japan that’s also a fairly old ancestry. And none of these look like present-day East Asians today. We know that the Tianyuan individual, their ancestry had to have persisted in some form until more recently. Because you see, in Native Americans, some groups have a little bit more shared affinity to this guy than others do, which suggests that they must have been carrying some Tianyuan-like ancestry, some of the groups when they were crossing the Bering Strait.

This Tianyuan ancestry, a big question, I think, still remains of like, how long did it last in China? They were in Mainland Asia. Who did it contribute? Is there any evidence left of their ancestry up until more recent times? And so a lot of people are interested in that question, especially in my lab in China.

ALEX LIM: So he’s not like a direct ancestor. He’s like a cousin.

MELINDA YANG: Yeah, yeah, a cousin, a first cousin, third cousin, something like that– or twice removed, maybe that’s the right word.

ALEX LIM: Twice removed, right. And then you said he’s related to Native American populations?

MELINDA YANG: There was this interesting find in South America, solely comparing present-day humans with each other. What they found was that some groups in South America shared a little bit of a connection to groups in Papua New Guinea, in Australia, and in the Andaman Islands off the coast of India. And so these three groups that they were looking at, they split off really, really early for non-African populations. They have this very old ancestry there, that if you were to look at them, it sort of dates back into the first movements of modern humans across Eurasia. They have this connection.

But it’s really weird, because they obviously weren’t able to cross the giant Pacific Ocean to get to the Americas. There’s no evidence that suggests that could occur. And so they believe that, potentially, there was some ancestry that was related to them that was in mainland East Asia that contributed to them and that was carried over across the Bering Strait as well. And it’s something that we don’t have an individual for.

And it’s when we saw that Tianyuan individual showed that same connection, that was sort of like a smoking gun of like, oh, there’s definitely things in mainland East Asia that shares these very, very early ancestry-like things. That’s still just a vague hint, so I think we’re still looking in East Asia to find something else that really, really clearly shows this connection between now Beijing area and then Papua New Guinea and the Americas. But then the fact that we have something in mainland Asia was sort of a big find for us.

ALEX LIM: So yeah, so then what is your study and finding Tianyuan, what is it filling in about our understanding of ancient East Asia?

MELINDA YANG: Pre-Neolithic, there was all these different types of very, very diverse Asian ancestries. All of them are no longer found on their own today. They sort of maybe pop up in a few places in admixed form, but they’re mostly not represented. And then you have this wave of some other ancestry that is now everywhere across present-day East Asia.

Farming definitely played a role. I think we see that over here. But then it seems a bit more complex than that because there are non-farming groups in the south that are more closely related to those farming groups and not to those Paleolithic hunter gatherers, like Tianyuan.

This is all speculation over here. But I think that sort of suggests that there’s a lot more population movement than people are normally thinking of with hunter gatherers in mainland East Asia. But to get at that genetically, we have to find a lot more samples and be able to get ancient DNA out of them.

ALEX LIM: I’m Alexa Lim, and this is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. There’s a lot of different ways to study history, even ancient history. The way you do it, why is that interesting to you?

MELINDA YANG: My interest in this dates back to high school, where I really became interested in archaeology because I was interested in all the different ways, how we can study humans. It’s like a giant mystery, where you can ask these questions about how they live, what were they eating? What were they throwing away? What were they keeping and burying with them that were things of value? And then sort of get at their motivations for why they were doing certain

Things. And I loved that. I visited Jamestown when I was in ninth grade, and there was an archaeologist trying to tell us about that. And I was like, this is really neat that you can tell these things not by looking at written text. So I think that was sort of the first seed of being interested in human history.

How did I end up on a computer coding trying to compare genetic patterns? And so in college, I was trying to better understand the genetic aspects of this. And then what I was discovering is that people were better able to sequence humans, sequence anything, and then so you could start getting massive amounts of DNA from many, many different populations. It’s becoming a big data question.

I was interested in, how is it that I can look and analyze big data that’s coming from DNA and assess individuals from across different regions across the world to address what I think is the most interesting questions about human prehistory, like how their biological movements connect to what’s observed culturally, in their pottery, in their tools, and how that’s shifted over time?

ALEX LIM: You’ve studied another population in Asia. I’m talking about pandas. You looked at the genome of a 22,000-year-old panda.

MELINDA YANG: Yeah. So when you learn how to do the methodology, humans really aren’t that different from all the other organisms out there. But this individual, this specimen was from Guangxi, which is one of the most southern provinces of China. And it’s not an area where you find pandas today.

So 22,000 years ago, when this panda was alive, there was obviously the pandas that would lead to the present-day pandas that we don’t have good examples for. But then there was also much, much different-looking pandas genetically. And then so there was a high amount of genetic diversity that was present in pandas in the past.

I don’t know what their fur color would have looked like. But the reason that we were even looking at this specimen is because it’s skeletal morphology– so all we had was its skull– was very similar to pandas. So I don’t think that if we were to walk in and see this individual in a zoo, we would say, like, oh, hey, this is a panda. But people who study pandas and who know what are the important sort of features about them looked at the skull, and they were like, OK, this is definitely a panda that we had in the past.

ALEX LIM: Like you said, you can apply it to anything. Thanks for joining us.

MELINDA YANG: Yeah, thanks for having me. It’s cool to be able to talk about my research over here, especially since I think a lot of people don’t know very much about northern and southern East Asia.

ALEX LIM: Melinda Yang is a professor of biology at the University of Richmond in Virginia. This is Science Friday. I’m Alexa Lim.

Copyright © 2020 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Alexa Lim was a senior producer for Science Friday. Her favorite stories involve space, sound, and strange animal discoveries.