Flu’s Fatal Side Effect: Heart Attacks

11:31 minutes

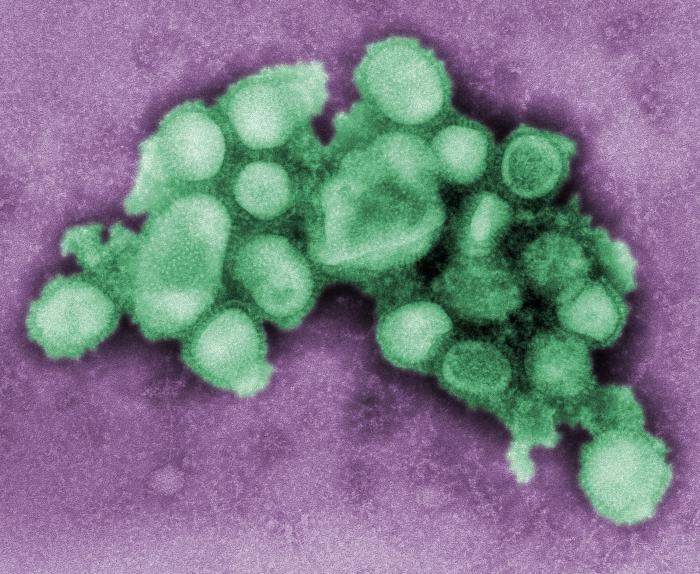

During a particularly nasty flu season, cutting exposure to the virus may be more important than ever for older adults at risk of heart attack. A study in the New England Journal of Medicine found a six-fold increase in heart attacks among seniors with confirmed cases of the flu, compared to periods when they were well.

“What we’re highlighting is that while influenza can cause mild illnesses in most people, and especially younger and healthy people, it causes some pretty devastating illness for some, especially those at higher risk of having a heart attack,” says Dr. Kevin Schwartz, an infectious disease physician at Public Health Ontario, and an author on the study. “So, it’s very important especially for those groups and anybody who’s at risk of heart attack to get their vaccine.”

What’s more, the flu virus doesn’t even require a cough or sneeze to spread. According to another study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, even regular breathing can expel the infectious virus into the air and onto nearby surfaces. That means regular hand washing is even more important during flu season.

Schwartz joins Science Friday to discuss his team’s work on the virus, and the hunt for a more long-term solution to the flu: a universal vaccine.

Kevin Schwartz is an infectious disease physician with Public Health Ontario, and an adjunct scientist in the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences in Toronto, Ontario.

IRA FLATOW: Next up with the flu season– as we keep saying, it’s in full swing– now comes word it’s just not sniffles and fevers and aches and pains we need to worry about. A new study out this week in the New England Journal of Medicine suggests that your risk of heart attack can be up to six times higher when you have the flu, especially if you’re an older person. And it’s not just the flu virus that boosts that risk. Dr. Kevin Schwartz is one of the authors of that study and an infectious disease physician at Public Health Ontario in Toronto. He joins us from the CBC there. Welcome to Science Friday, Dr. Schwartz.

KEVIN SCHWARTZ: Thanks for having me.

IRA FLATOW: Tell us about your study. How did you come to the conclusion that the flu might boost the risk of heart attack?

KEVIN SCHWARTZ: Sure– so what we did in this study is we looked at a cohort of patients with laboratory confirmed influenza and we then looked at the risk of heart attacks within seven days of influenza infection compared to other periods of time– that would be one year before or one year after the influenza infection. And what we found was, as you mentioned, that six-fold increased risk within that one week risk period after influenza infection compared to those controlled-time periods.

IRA FLATOW: Hmm– and did you test for other viruses too, like cold viruses– stuff like that– that might have an effect on the risk of heart attack?

KEVIN SCHWARTZ: Absolutely, yeah. So we did that, and that was a little bit surprising. We didn’t expect to find differences for all the other viruses.

We were able with our sample size to look at RSV, or respiratory syncytial virus. And we found a significant association, although it was lower than influenza. It was 3.5 was the increased risk. We looked at all other viruses that were not influenza and not RSV. And, again, we found a significant association, and that was–

IRA FLATOW: Hmm.

KEVIN SCHWARTZ: –2.7, roughly, increased risk during that risk interval. We’ve also looked at negative swabs– so nasal swabs tested for viruses that we did not detect any– and that’s probably a mix of different conditions, either viruses that weren’t tested for or perhaps bacterial pneumoniae and other infectious conditions. And we also did see a significant risk, although a smaller one, for that group as well.

IRA FLATOW: So how would a viral infection affect your heart?

KEVIN SCHWARTZ: Yeah– that’s a good question. I mean the leading theory is that you get this inflammatory response from influenza. That inflammation in the body changes your platelets, it changes your clotting risk, and it can precipitate clots in the coronary arteries, leading to a heart attack. We know that influenza also increases your metabolic demand. It causes your heart to race, and that stress on the body–

IRA FLATOW: Hmm.

KEVIN SCHWARTZ: –also probably contributes to somebody who’s already at risk of heart attack then developing a heart attack in relation to the stressor.

IRA FLATOW: So what group in the population is at the highest risk?

KEVIN SCHWARTZ: Yeah– so the population in the study were generally those who were at risk of heart attacks, so above the age of 65 were most of them. A lot of people in the study had diabetes, high blood pressure, high cholesterol. This study didn’t have the sample size to differentiate those different risks, but certainly the risks seemed higher, at least for those older in the study, but we weren’t able to tease it out. But, certainly, those at higher risk of heart attacks are likely to be at higher risk of having one after an influenza infection.

IRA FLATOW: Hmm– so if it’s possibly inflammation, would taking some of the NSAIDs or the other inflammation-dampening drugs be helpful during–

KEVIN SCHWARTZ: Really good question–

IRA FLATOW: –that?

KEVIN SCHWARTZ: –I mean we honestly don’t know the answer to that. There is some data that taking antivirals and antiinflammatories together when you have an influenza infection may improve the symptoms overall. Now, whether or not they actually would reduce an event like a heart attack afterward is a really interesting and important question that we don’t have an answer to that right now.

IRA FLATOW: Mm-hmm. There was another study out this week in the proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that says coughing and sneezing aren’t necessary to spread the flu. All you need to do to get the virus is to be around someone who’s breathing, who has the virus. It’s pretty scary. We all thought you had to be sneezed on.

KEVIN SCHWARTZ: Yeah, no. It’s definitely an interesting study. I mean we know that influenza is very contagious. So I mean that–

IRA FLATOW: Yeah.

KEVIN SCHWARTZ: –is certainly not new. I think where that study was interesting is that they looked for larger particles. And now for large particles, you need to be close to somebody, right? You need to be within probably six feet of them when they’re projecting those particles for you to catch the infection.

The study showed that even smaller particles of influenza that may float around the air at further distances are probably present. And what’s interesting is it’s not just from coughing or sneezing, but they’re present from normal breathing. And I’m certainly not surprised by that finding. They did show in that study that if you’re coughing, you are going to spread more of the virus, which is going to make it more contagious. But, certainly, just being near someone who is sick is theoretically impossible to catch influenza that way.

IRA FLATOW: Oh, like just being near somebody [INAUDIBLE] not going to do. How long does the flu virus actually hang out, let’s say on a subway pole or handle of something?

KEVIN SCHWARTZ: Yeah, it depends on the type of surface. But most of the time, it would only be anywhere from a few hours to up to two days. And there are some studies showing that you can recover virus from some surfaces 48 hours after it was put there. So it is possible to get it from things like door handles and the subway for up to a couple of days.

IRA FLATOW: I have heard that there’s something like a three foot rule in hospitals. What’s that about? Should I start getting at least three feet away from sick people?

KEVIN SCHWARTZ: Yeah, and that’s how we tend to design where we place beds that are in the emergency room and things like that to try and prevent spread from one patient to another. And so, usually, most droplets spread like how influenza and the common cold are typically spread. It’s going to come out of somebody’s mouth with a cough or with breathing, and then it’s going to fall usually within a few feet of that person. So if you’re designing a hospital or you want to try and avoid catching these viruses, if you’re staying within further than three-to-six feet away from somebody, you’re certainly going to decrease–

IRA FLATOW: Hmm.

KEVIN SCHWARTZ: –the risk of it being spread.

IRA FLATOW: You know what’s funny is that we did a video a few months ago about the hospital or ventilation systems– a sneeze. It was a video about sneezing. And it showed that when somebody sneezes, all the droplet particles– if it’s a typical ventilation system– go up into the ceiling right into the intake [LAUGHTER] of the air system for the hospital or the office– the worst place you could send it. And that’s just where they tend to go– so. [LAUGHTER]

KEVIN SCHWARTZ: Yeah, it’s very scary. It’s movies like Outbreak that make things perhaps a little more scary than they really are. Most infectious diseases do not spread that way. I mean there are examples like tuberculosis, measles, and chicken pox, for instance, that are very contagious.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah.

KEVIN SCHWARTZ: They’re small droplets, and they spread through the air. So you could be in a totally other part of a room or even in a different room and potentially catch some of those infections. Most things like influenza, common colds are not as contagious.

IRA FLATOW: Hmm.

KEVIN SCHWARTZ: You really need to be in direct contact or within a few feet of somebody to catch those infections.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday from PRI, Public Radio International, talking about the flu with Kevin Schwartz, infectious disease doctor at Public Health Ontario in Toronto. Let me take a call. I have Ken from South Florida. Hi Ken, welcome to Science Friday.

KIA: Hi, how are you?

IRA FLATOW: Hi there.

KIA: It’s actually Kia.

IRA FLATOW: Oh, I’m sorry.

KIA: Yeah, so– that’s OK– so last year, my son was at a friend’s house who had the flu. And everywhere I was trying to get him a flu shot, all the pharmacists I spoke with– like CVS and all of them– said that they wouldn’t necessarily give him the flu shot because it’s not going to do anything for him because he’s been already exposed. So this year– I normally– let me preface this by saying I don’t get the flu shot– I don’t give it to any of my children– we have four. This year, unfortunately, he got the flu. And when we went to the doctor, she said that he had the type of flu that had already mutated, like there’s no vaccination for it and he’s just going to have to sweat it out or wait it out.

The scary part, though, is he was having– he’s an athlete– and he was having the most scariest heart palpitations. And I had never heard of that before. And then I started trying to research it and called the doctor and they said, of course, because it affects the muscles and it affects the heart muscles. And so I’m just curious.

IRA FLATOW: So you’re worried– you’re scared– you’re worried. Well, let me see–

KIA: I was, yes.

IRA FLATOW: We don’t like to talk about individual cases, but I’ll see if I can get you some free medical help. Kevin Schwartz, what do you think?

KEVIN SCHWARTZ: Yeah, let me make a couple of comments to that. So I just want to stress that we use the term flu very loosely. So often we think when people say flu, we don’t necessarily differentiate between influenza infection and other viruses that cause cold and flu-like symptoms. So the influenza vaccine only protects against influenza. And it’s actually very difficult to differentiate those different types of viruses without a test in the laboratory.

IRA FLATOW: So–

KEVIN SCHWARTZ: Umm– yeah– go ahead.

IRA FLATOW: –as far as she’s concerned, does she have cause for worry about her son?

KEVIN SCHWARTZ: No, and so what I would say is the influenza vaccine protects against multiple different strains of influenza. So, for instance, like this year, there is a quadrivalent– or a four– influenza vaccine that covers four different strains, which is recommended for children. And so even if you had one type of influenza–

IRA FLATOW: Hmm.

KEVIN SCHWARTZ: –it’s still recommended to get the flu shot, because you’re going to be protected–

IRA FLATOW: So–

KEVIN SCHWARTZ: –against those other strains.

IRA FLATOW: –so he should get the flu shot, but he’s already got some flu and she’s concerned about his muscle [INAUDIBLE]

KEVIN SCHWARTZ: Yeah, so even if you’ve had flu-like illness or even if you’ve had laboratory confirmed influenza infection that year, there’s good reason to get the flu shot that year still to protect against those other strains. And we tend to see things like influenza B come later in the year in most years, although this year is the exception to that– is that we’re seeing influenza A and B come up simultaneously.

IRA FLATOW: Mm-hmm. And last week we talked about one universal flu vaccine idea. And this week, there was a study exploring using nanoparticles that was very effective in laboratory animal tests. So I guess they are making some progress in trying to come up with a universal vaccine

KEVIN SCHWARTZ: Yeah, this is the holy grail of really influenza vaccine development. It’s been very challenging just because the part of the flu virus which induces that immune response is changing almost year to year, and–

IRA FLATOW: Hmm.

KEVIN SCHWARTZ: –that immune response is not long lasting.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah.

KEVIN SCHWARTZ: So it’s a really interesting, I think, technology and approach that those researchers are taking to try and take part of the flu virus that does not mutate–

IRA FLATOW: Right– right–yeah.

KEVIN SCHWARTZ: –and then make it induce an immune response that it’s going to be long lasting.

IRA FLATOW: Dr. Kevin Schwartz, infectious disease physician at Public Health Ontario in Toronto, thank you for taking time to be with us today.

KEVIN SCHWARTZ: Thanks so much for having me.

IRA FLATOW: And if you want to check out any of the studies we mentioned today, we have them all linked up at sciencefriday.com/flu.

Copyright © 2018 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Christopher Intagliata was Science Friday’s senior producer. He once served as a prop in an optical illusion and speaks passable Ira Flatowese.