Former Michigan Governor, Other Officials Charged for Flint Water Crisis

5:29 minutes

This segment is part of The State of Science, a series featuring science stories from public radio stations across the United States. This story by Steve Carmody originally appeared on Michigan Radio.

This segment is part of The State of Science, a series featuring science stories from public radio stations across the United States. This story by Steve Carmody originally appeared on Michigan Radio.

In Flint, criminal and civil cases stemming from the city’s lead tainted drinking water crisis are converging this week. New criminal charges may be coming while many in Flint still question whether they will ever get justice.

Nearly seven years ago, government leaders here pushed the button that switched the city of Flint’s drinking water source from Detroit’s water system to the Flint River.

The intent was to save money. The result was a complete disaster.

Improperly treated river water damaged pipes, which then released lead and other contaminates into the city’s drinking water. Eighteen months later the water was switched back, but the damage was done.

Blood lead levels soared in young children. People were forced to use bottled water for drinking and washing clothes. The city was forced to rip out thousands of old pipes.

While testifying about the Flint water crisis before Congress in 2016, former Governor Rick Snyder acknowledged the mistakes.

“Local, state and federal officials, we all failed the families of Flint,” Snyder told a congressional committee.

Snyder was not among the 15 state and local government officials who faced criminal charges for their handling of the crisis. Half of them pled guilty to lesser charges in exchange for no jail time. And in 2019, Michigan’s new Attorney General dropped charges against the remaining defendants citing problems with the original investigation.

The investigation seemed over.

Until Tuesday, when the Associated Press reported that several former government officials, including former Governor Snyder, would be facing new charges. If that happens, legal experts say it would be a difficult case for prosecutors.

Peter Hammer teaches law at Wayne State University in Detroit. He says, despite possible difficulty getting convictions, it’s important to bring charges.

“Especially in an era where we are living where people are not being held accountable. This could be an important sort of statement about the significance of the rule of law and that not even the highest public official is the state is going to get off scot-free,” says Hammer.

An attorney for former governor Rick Snyder calls the reports of impending charges “a public relations smear campaign”, saying that if brought they would be “meritless.”

Since enduring 18 months of foul smelling, dirty tap water that made them sick, Flint residents have demanded justice and compensation.

A U.S. District Court judge is expected to decide in the coming days if she’ll give preliminary approval to a massive settlement agreement resolving most of the thousands of outstanding lawsuits.

Last year, the state of Michigan announced it struck a deal with attorneys representing Flint residents to pay $600 million into a settlement fund. A few months later, the city of Flint, a local hospital and an engineering firm agreed to chip in another $41 million.

Nearly 80% of that money would be set aside for plaintiffs who were young children or minors during the crisis. They are the ones most at risk for suffering long-term lead related health problems.

But a growing chorus of critics say it’s not enough.

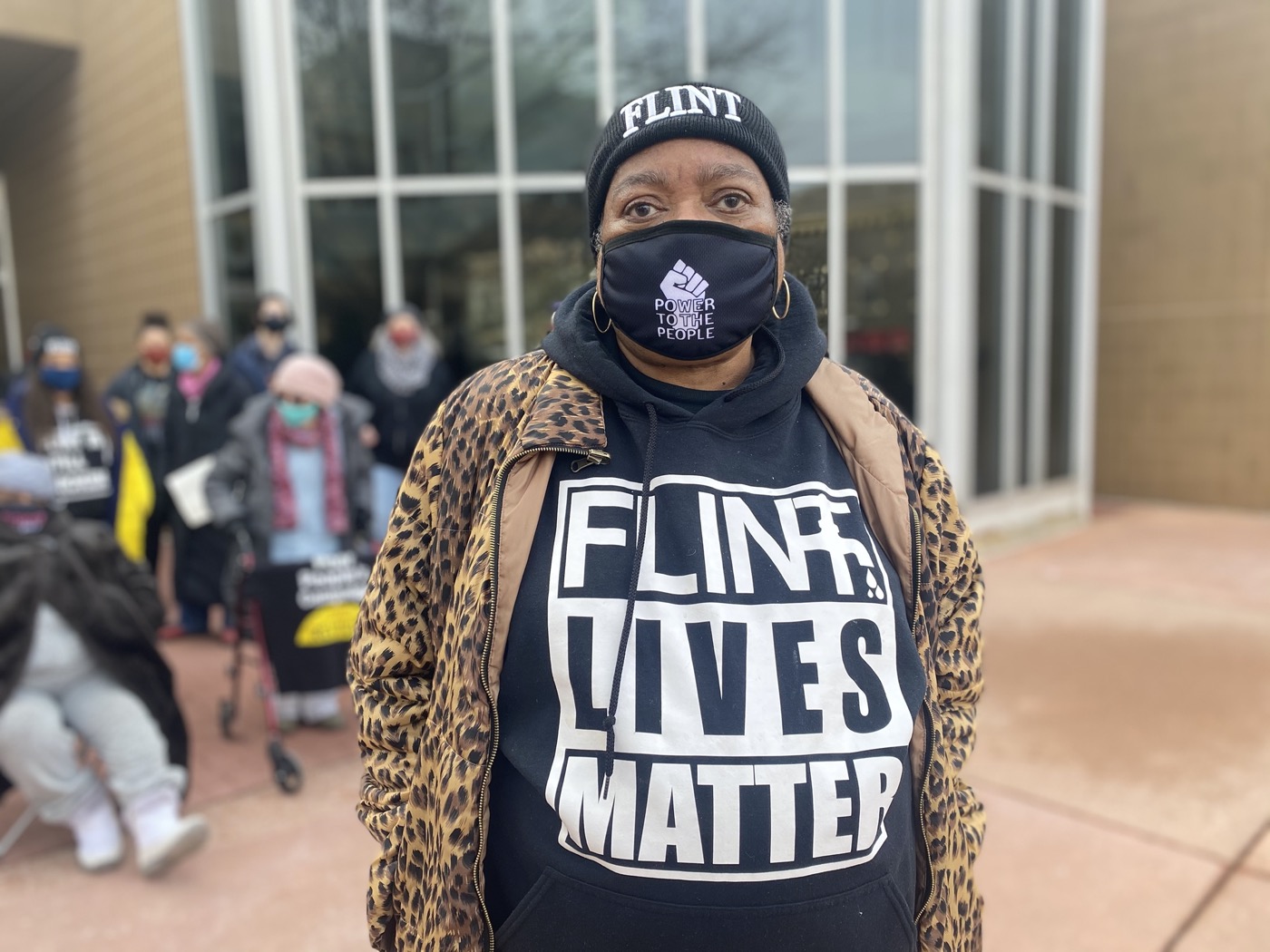

A group of Flint civic and religious leaders gathered Monday outside the city’s water plant to express concern about settlement.

“We believe the proposed settlement as currently allocated is just as disrespectful as the injury caused by the water crisis tragedy itself,” says Pastor John McClane.

In addition to tens of thousands of Flint residents, there are the lawyers. Lots of them. More than 140 took part in a zoom hearing with the judge last month. This is part of the challenge facing judges: how to divide a large pool of money without leaving some feeling victimized again.

Flint’s mayor says it’s important his residents have “a belief in justice” and developments this week may help with that.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Steve Carmody is the Flint reporter for Michigan Radio in Flint, Michigan.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. Time to check in on the state of science.

OVERLAPPING VOICES OF RADIO ANNOUNCERS: This is KER– For WWNO– St. Louis Public Radio– Iowa Public Radio News.

IRA FLATOW: Local science stories of national significance– it’s been about seven years since the Flint, Michigan water crisis began. In 2014 the city changed its water source from Detroit’s water system to the nearby Flint River in an effort to save money. But officials didn’t treat the water properly, so lead from the aging pipes leached into the water, exposing over 100,000 residents to high levels of the neurotoxin.

Over the past few years, charges have been filed against some officials. Some pled no contest. And then in 2019, the remaining charges were dropped. Then just last week, nine officials, including former Michigan Governor Rick Snyder, were charged for their roles in the crisis.

So what does this mean for getting justice to impacted residents? Joining me today is someone who has followed this crisis closely from the beginning– Steve Carmody, Flint reporter for Michigan Radio based in Flint. Welcome, Steve, to Science Friday.

STEVE CARMODY: Thank you.

IRA FLATOW: As I said, we’re almost seven years out from the start of this crisis. Were these charges against the former governor and those other officials a surprise?

STEVE CARMODY: The timing was definitely a surprise. Ever since the attorney general ended an original investigation and started a new one, her office has been very quiet about what’s actually been happening with the investigation. So when we learned last week that these charges had been filed, that was a surprise.

But most of the people who are facing charges, though, had been charged previously in the original investigation. They’re facing additional charges beyond what they were charged with before. And the big surprise was that the former governor was also being charged, although he’s only being charged with two counts of neglect of duty, which is a misdemeanor.

IRA FLATOW: How are these officials implicated in the Flint Water Crisis?

STEVE CARMODY: Well, for the most part, the people who have been charged in this are state officials. And it’s important to remember that in 2014, the City of Flint was under state oversight. The governor had appointed an emergency manager to run the city to correct a financial problem the city was having. So the decision to switch the city’s water was made by those emergency managers.

And two emergency managers are among those who’ve been charged in connection with the water crisis. And several state health officials, former state health officials, have also been charged with various things, including involuntary manslaughter– charges that are connected to a Legionnaires’ disease outbreak that took place at the same time as the water crisis. So it’s the state’s oversight of the Flint Water Crisis which is highlighted by the charges that have been filed.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s talk about the residents of Flint for a moment who were affected by this crisis. What are they saying about these charges?

STEVE CARMODY: Since the very beginning, people in Flint have wanted state officials to be held accountable for causing the water crisis in their community. And at the top of their list was Governor Rick Snyder. So when they learned that the governor was going to be criminally charged in connection with the crisis, there was a lot of excitement, a lot of “finally” that you were hearing around town. But Flint residents like Claire McClinton said they were disappointed when they heard what the charges are actually going to be.

CLAIRE MCCLINTON: You know, for a minute we felt good because that’s one of the things we’d been wanting on the criminal side of the case. But we also said in interviews we hope this charge reflects the damage that was done. And it wasn’t. We’ve been through too much to say we accept it.

IRA FLATOW: You know, as I said before, we’re almost seven years out from the start of this crisis. What do we know about how the health of these residents have been impacted over these last seven years and going forward?

STEVE CARMODY: At this point, it’s still being studied. We don’t know all the effects that people have had from the high lead exposure and also the exposure to other contaminants, including possibly Legionnaires’ disease. There’s been a lot of focus of studying the effects on young children, children who were six years old and younger, you know, since they are the ones who will be most likely to be affected by a heavy exposure to lead. And those children are just now– the youngest of those– are just now reaching the first grade and kindergarten. So we’re only just now beginning to get a better sense of how their cognitive abilities have been affected by the exposure to the lead.

IRA FLATOW: Is there any way to repay folks affected for their troubles? Has there been financial restitution for the people impacted?

STEVE CARMODY: While we’ve talked a little bit about the criminal cases, at the same time, there have been a lot of civil lawsuits that have been filed. And this week, a federal judge has given preliminary approval to a $641 million master settlement for many of those lawsuits against the state of Michigan, the City of Flint, and some private businesses as well. But there is still more litigation out there that isn’t covered by this master settlement agreement. So while the criminal charges may be just getting restarted, we are actually a little further down the line when it comes to what’s going to be happening on the civil side and people seeking damages for what’s happened to their health and what’s happened to their property.

IRA FLATOW: Steve, thank you for keeping us up to date.

STEVE CARMODY: You’re welcome.

IRA FLATOW: Steve Carmody, Flint reporter for Michigan Radio, based in Flint.

Copyright © 2021 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Kathleen Davis is a producer and fill-in host at Science Friday, which means she spends her weeks researching, writing, editing, and sometimes talking into a microphone. She’s always eager to talk about freshwater lakes and Coney Island diners.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.