FDA Approves First Breathalyzer COVID Test

12:03 minutes

The FDA approved a new COVID breathalyzer test, which gives results in just three minutes. It’s the first test that identifies chemical compounds of coronavirus in breath. The testing unit is about the size of a piece of carry-on luggage and is intended to be used in medical offices and mobile testing sites.

Nsikan Akpan, health and science editor at WNYC Radio based in New York City, talks with Ira about this new COVID test and other science news of the week, including new research on ocean warming and storm frequency, the story behind moon dust that sold for $500,000, and President Biden’s decision to allow higher-ethanol gasoline sales this summer, which is usually banned from June to September.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Nsikan Akpan is Health and Science Editor for WNYC in New York, New York.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. Later in the hour, why are COVID case counts becoming less accurate? And what’s the best way to think about your individual risk in the absence of good data? Plus, how to save the world with just a trillion dollars. We’ll be digging into some possibilities with hefty price tags.

But first, the FDA has approved a new COVID test this week– a breathalyzer that gives results in just three minutes. Hmm. Joining me now to talk about that and other science news of the week is my guest Nsikan Akpan, health and science editor at WNYC Radio, based in New York City. Welcome back.

NSIKAN AKPAN: Hi. How are you?

IRA FLATOW: Tell us about this test. Yeah, it’s called InspectIR COVID-19 Breathalyzer. And the FDA says in testing, it’s shown, like, 91% sensitivity and 99.3% specificity. So that would actually put it in the realm of PCR testing in terms of its accuracy and precision.

It can only be administered by a trained health professional. And it sounds like the company is still sort of building out its capacity to actually make these instruments and get them into clinical spaces. But the advantage of it is it can do a test in about three minutes, which would be really fast. And obviously, you don’t have to have something jammed up your nose, coming close to swabbing parts of your brain.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, and you could put it some other place, you know, where you need to have quick results, and get it to work.

NSIKAN AKPAN: Yeah, exactly. And we’re seeing real issues with testing right now in terms of demand. And so maybe this could attract people back to testing sites.

IRA FLATOW: That’s a good point. Let’s move on to some more COVID news, news of some new subvariants. What’s the latest?

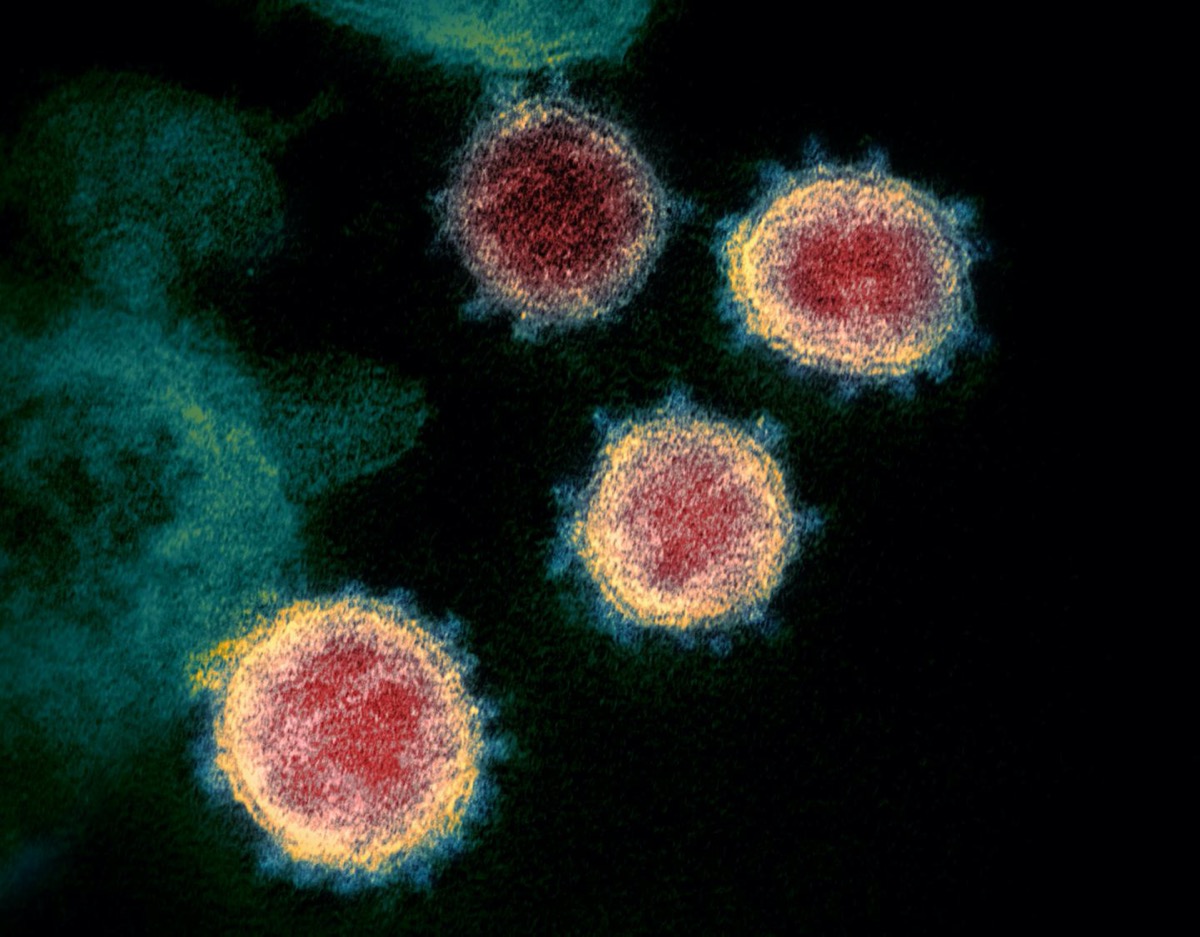

NSIKAN AKPAN: Yeah, so Omicron subvariants are becoming a bit of an alphabet soup. You know, I think a quick recap– Omicron is itself a variant of concern of the original coronavirus, like Alpha and Delta that came before it. But as Omicron has mutated over time, as all viruses do, it’s been yielding these new subvariants that spread faster and faster than what’s considered the original Omicron.

So the world started off getting pounded by B.1.1.529 and BA.1. And then BA.2 showed up essentially kind of around the same time, but for whatever reason it kind of sat in the background. Around the start of the year, BA.2 started to get a foothold in places like Denmark and the United Kingdom and other places, causing surges within already ongoing surges. There’s data from Denmark showing cases going up and then down and then up again. And that’s because BA.2 spreads about 30% to 50% faster than Omicron.

Now, this week, the World Health Organization is warning of new spinoffs called BA.4 and BA.5 because those versions are accounting for a growing share of cases in South Africa and Botswana, even though overall cases remain low. The White House is telling folks to remain calm, because so far BA.4 and BA.5 appear to be similar to BA.2. But personally, I’m mostly annoyed that the virus is clearly fine-tuning itself.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. I think we’re all annoyed about that, absolutely. Let’s hit some energy news. This week President Biden announced that he’ll allow E15 gasoline to be sold temporarily this summer. Give us a little refresher what the E15 means in the gasoline, and why is it usually banned in the summer?

NSIKAN AKPAN: Yeah, you know, so that number E15, it refers to how much ethanol is blended into gasoline. So about 98% of US gas stations typically offer E10, so it’s 10% ethanol and 90% gasoline. E15 ups the blend to 15% ethanol. You know, it makes it more dilute, so you can spread your gasoline a little bit further.

Ethanol, it’s made from corn, hence why President Biden made the announcement in Iowa. So it’ll really push demand for corn and also for corn-based biofuels. And during the announcement, the White House pegged these biofuels as a way to reduce carbon emissions. But you know, that particular claim about biofuels has really come into question in recent years.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, and the whole idea is supposedly, why you don’t want E15 in the summer is that the added ethanol makes more smog, right?

NSIKAN AKPAN: Yeah, exactly. There have also been studies looking at just how much carbon is made during the entire production of ethanol. So Tim De Chant had this great article in Ars Technica in February that they resurfaced this week about a study that was trying to measure that, the carbon contribution of just making ethanol for biofuels. And essentially, what it comes down to is, due to the use of fertilizer to make the corn and also the land use, harvesting the corn, all of those things, if they themselves are not powered by renewable energy, then you can actually have the production of biofuels lead to a net increase in the amount of carbon that gets released into the atmosphere.

IRA FLATOW: So net you’re not really saving any– your carbon footprint’s getting bigger, actually, instead.

NSIKAN AKPAN: Exactly. Exactly. You know, and if the energy that supports the production of biofuels could be sourced from renewable places, then biofuels could be this great thing that we could add into the mix for our energy needs. But it’s a struggle.

IRA FLATOW: Right. Speaking of energy and warming climate, there’s a new study that tracked how the warming climate is affecting the Atlantic hurricane season from 1982 to 2020 that appears to change our ideas about the number of hurricanes on our warming planet. Tell us about those findings.

NSIKAN AKPAN: This story really stuck out to me– and it’s by Bob Berwyn over at Inside Climate News– because many studies looking at the connection between hurricanes and climate change kind of focus on the intensity, right? The idea that, oh, these storms might have more rain or stronger winds over time, or that, oh, the storms appear to be halting or stalling whenever they get close to the coast.

Bob spotted a study published this week in weather and climate dynamics that looks at whether or not we’re seeing more hurricanes every single hurricane season. So I think past couple of years, we’ve kind of run out of names, alphabetical names, for these storms, and we’ve had to switch to letter systems in order to–

IRA FLATOW: Greek letters instead of the names.

NSIKAN AKPAN: Yeah, exactly. And so what this study is saying is like, oh no, those types of seasons where we’re running out of names, where we’re just having so many storms over and over and over again, those appear to be becoming more frequent over time. So it kind of gets at this question of the frequency of hurricanes due to climate change, which has been very hard to answer.

IRA FLATOW: And that’s interesting because the common wisdom for the last few years has been, oh, yeah, we’re not getting more hurricanes. They’re just getting more intense. And this seems to say we are getting more hurricanes.

NSIKAN AKPAN: Yeah, exactly. And this is just one model. And of course, we’ll have to see if other scientists can replicate this research, if they can build similar models that take in the variables that they were looking at and find something similar. But it does sort of point us in the direction of saying, hey, we’re getting more storms, which can be really bad, especially for island nations where these storms are more likely to hit.

IRA FLATOW: Right. Let’s head in the opposite direction, from the oceans up into space. This next story is a bit of a wild ride. Let me go to the end of the ride. It ends with a pinch of moon dust collected by Neil Armstrong on the moon selling for half a million dollars. Give me the back story on that.

NSIKAN AKPAN: Yeah, this is a great piece from Maya Wei-Haas at National Geographic. And I would describe it as perfect for, like, a Netflix crime caper series.

IRA FLATOW: [LAUGHS]

NSIKAN AKPAN: So essentially, Neil Armstrong, he collected this dust from the moon, and he was putting it into bags, and he brought it back down to Earth. I guess at some point NASA loaned one of those bags to a museum in Kansas. And it turned out that I guess the museum director had a bit of a side hustle where they would sell off certain artifacts from the museum.

So essentially, what happened is that this bag got sold. And then the person who bought it was like, oh, I want to see if this is authentic, right? So they sent it to NASA. And NASA was like, yeah, this is our bag. How did you get it?

NASA wouldn’t give it back. The person sued. The person won. They got the bag back. But then it turned out NASA had kept some of the dust from the bag. And it just raises all types of really interesting questions about property rights when it comes to stuff that comes from space.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, who has a right to anything from the moon, right?

NSIKAN AKPAN: Exactly. We have international space law treaties that kind of regulate activities in space, sort of like how many satellites we can put up, military activities. But it’s a really interesting question, right?

Like, who owns the moon? Is it the first person that gets to the– does Neil Armstrong own the moon? Or if dust comes back from the moon, or if it comes back from Mars, do we all own it? You know, because space kind of– the universe is kind of for everybody.

IRA FLATOW: Exactly. Exactly. It’s sort of one small speck for man, one giant conundrum for mankind.

NSIKAN AKPAN: Yeah. Yeah, no, I mean, it also raises all types of conundrums, like what would you do with moon dust, right? Do you just leave it on a plate in a glass case? Do you eat it to try to absorb the powers of the moon? No, that’s a joke.

IRA FLATOW: [LAUGHS]

NSIKAN AKPAN: That’s a joke.

IRA FLATOW: Let me get to a quick final question. Let’s continue our journey into space. In the coming months, both SpaceX and NASA are launching two big rockets.

NSIKAN AKPAN: Yeah, you know, this summer is going to be really great for rockets, or people who love rockets. And Jonathan O’Callahan at Scientific American has a great deep dive into SpaceX’s Starship rocket and NASA’s Space Launch System, or SLS. Both are slated to launch, have official launches this summer.

And both are kind of designed to be able to carry really heavy loads. You know, so for instance, if we want to put the James Webb Space Telescope into orbit now, it has to be kind of folded up. It has to be sort of sent up in a way that it can be– the final assembly or the final unfolding can happen in space. These rockets would allow us to just send up really big things into space all at once. And so they would be really useful, or they’d be very useful, for potentially deep space missions– say, you know, going to the moon, going to Mars.

IRA FLATOW: We’ll look forward to a summer of rocketry. Thank you, Nsikan.

NSIKAN AKPAN: Yeah. Thanks for having me.

IRA FLATOW: Nsikan Akpan, health and science editor at WNYC Radio, based in New York.

Copyright © 2022 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Shoshannah Buxbaum is a producer for Science Friday. She’s particularly drawn to stories about health, psychology, and the environment. She’s a proud New Jersey native and will happily share her opinions on why the state is deserving of a little more love.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.