As Temperatures Rise, Farmworkers Are Unprotected

9:25 minutes

This article is part of The State of Science, a series featuring science stories from public radio stations across the United States. This story, by Mónica Cordero of Investigate Midwest and Eva Tesfaye of Harvest Public Media, was originally published by KCUR.

This article is part of The State of Science, a series featuring science stories from public radio stations across the United States. This story, by Mónica Cordero of Investigate Midwest and Eva Tesfaye of Harvest Public Media, was originally published by KCUR.

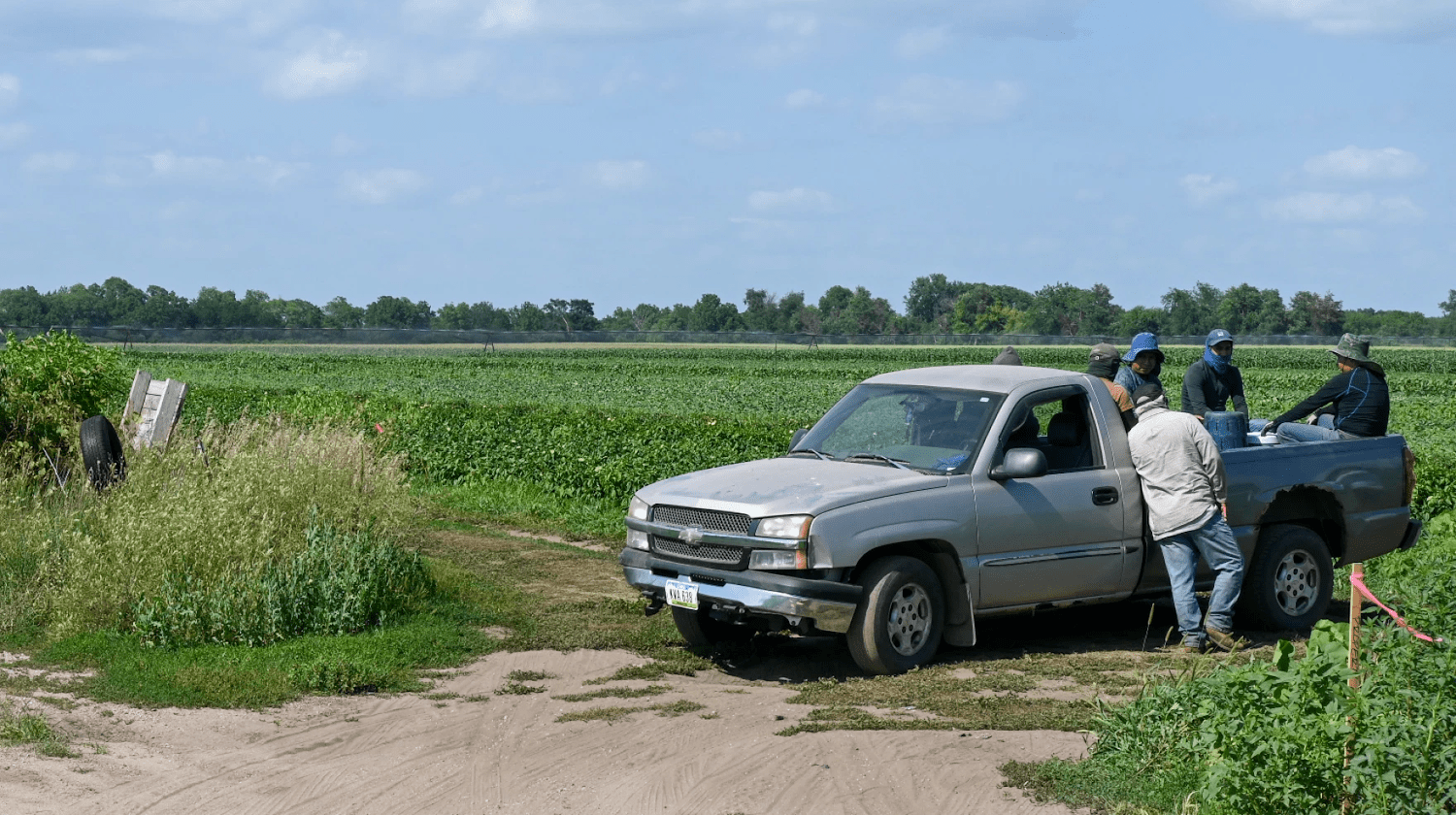

Juan Peña, 28, has worked in the fields since childhood, often exposing his body to extreme heat like the wave that hit the Midwest last week.

The heat can cause such deep pain in his whole body that he just wants to lie down, he said, as his body tells him he can’t take another day on the job. On those days, his only motivation to get out of bed is to earn dollars to send to his 10-month-old baby in Mexico.

Farmworkers, such as Peña and the crew he leads in Iowa, are unprotected against heat-related illnesses. They are 35 times more likely to die from heat exposure than workers in other sectors, according to the National Institutes of Health, and the absence of a federal heat regulation that guarantees their safety and life – when scientists have warned that global warming will continue – increases that risk.

Over a six-year period, 121 workers lost their lives due to exposure to severe environmental heat. One-fifth of these fatalities were individuals employed in the agricultural sector, according to an Investigate Midwest analysis of Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) data.

One such case involved a Nebraska farmworker who suffered heat stroke alone and died on a farm in the early summer of 2018. A search party found his body the next day.

In early July 2020, a worker detasseling corn in Indiana experienced dizziness after working for about five hours. His coworkers provided him shade and fluids before they resumed work. The farmworker was found lying on the floor of the company bus about 10 minutes later. He was pronounced dead at the hospital due to cardiac arrest.

“As a physician, I believe that these deaths are almost completely preventable,” said Bill Kinsey, a physician and professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “Until we determine as a society the importance of a human right for people to work in healthy situations, we are going to see continued illness and death in this population.”

Read the rest of the story on KCUR.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Eva Tesfaye is a reporter with KCUR, Harvest Public Media, Mississippi River Basin Ag & Water Desk in Kansas City, Missouri.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. And now it’s time to check in on the state of science.

[AUDIO PLAYBACK]

– This is KER–

– For WWWO.

– Saint Louis Public Radio.

– Iowa Public Radio News.

[PLAYBACK ENDS]

IRA FLATOW: Local science stories of national significance– being a farm worker in America is very hard, and it’s dangerous. Hundreds of millions of us have experienced a heat wave this summer. But for people working out in the fields to grow and harvest our food, that heat may be deadly.

My next guest reported on their struggle for Harvest Public Media, Investigate Midwest, and the Mississippi River Basin Ag, and Water Desk. Eva Tesfaye is a reporter for KCUR and Harvest Public Media based in Kansas City, Missouri. She reported this story with Mónica Cordero at Investigate Midwest. Welcome back to Science Friday.

EVA TESFAYE: Thanks for having me back.

IRA FLATOW: Nice to have you. OK, a lot of people have experienced the oppressive heat just walking around. But what makes agricultural workers so vulnerable to the heat?

EVA TESFAYE: Yeah. Obviously, a lot of them are working outside. It’s quite hard, physical labor, depending on what you’re doing. But yeah, usually it is. And because of that, they’re 35 times more likely to die from the heat. That statistic comes from the National Institute of Health.

Another reason that they’re particularly vulnerable is a lot of them are often paid by how much they pick. So if they’re picking apples, they’ll be paid by how much they get that day. So that can incentivize them to work harder, to keep going even if they’re feeling the effects of the heat in negative ways. And I heard that a lot of them don’t really feel like they have a choice.

I spoke to one farm worker. His name was Santiago. He wanted to not share his full name for privacy reasons. But this is what he said.

[AUDIO PLAYBACK]

– You got to support your family no matter what. You got like two or three kids, you got to work harder.

[PLAYBACK ENDS]

IRA FLATOW: And you’re talking about the kind of jobs they’re working at. These are really difficult, backbreaking jobs, right?

EVA TESFAYE: Yes. So typically, we see these farm workers working in specialty crops. So that’s like picking fruits and vegetables. The farmworkers I talked to in Missouri, they picked apples. And you can imagine those get really heavy after you collect more and more.

So you’re carrying that. And then you’re also climbing up a ladder to get the apples, which is dangerous if you’re feeling faint from the heat. And you’re out there all day in the heat, looking up at the sun because you’re looking up to get the apples. So a lot of them use eye drops and things like that.

Also here in the Midwest, we see a lot of farm workers doing detasseling, which is a job that typically used to be done by like high schoolers on their summer break. But now we’re seeing more farm workers come from Central America– through the H-2A program, people can come over to the US and work for the summer. Those are the two places that I’ve seen farm workers working in the Midwest. But obviously, on the coast, it’s definitely more of those specialty crops.

IRA FLATOW: I mentioned that this was a deadly kind of heat. How many deaths are we talking about here?

EVA TESFAYE: Yeah. So we found– Mónica Cordero, my colleague, found that there were 121 deaths related to heat. And that was from OSHA data from 2017 to 2022. That number is probably undercounted just because it is hard to classify a death as related to heat. Usually heat does aggravate conditions that the body might already have. A lot of people who have died from heat-related causes die from cardiac arrest.

And also this is just OSHA data. This is just data where OSHA went and inspected these fatalities. So it likely is more.

IRA FLATOW: Are there any regulations there for farm workers when it comes to heat waves?

EVA TESFAYE: Yeah. So there’s no specific regulations when it comes to heat federally. Only four states have regulations when it comes to outdoor workers and heat. And that’s California, Oregon, Washington, and Colorado. But OSHA is saying that, under the General Duty Clause, employers do have a duty to protect their employees from the heat. But some of the advocates for farm workers I talked to said that’s not enough. The onus is still on the employers to try to protect from the heat, and it would be better if there were some sort of standards.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. We know there’s a huge percentage of farm workers who are undocumented. How does this play into this issue?

EVA TESFAYE: Part of it is it makes it a really hard issue to research. Like I said, those deaths were probably undercounted. We don’t really know the population size of farm workers in the US because many of them are undocumented. So it makes it hard to know the amount of heat illness cases, how to know the amount of heat-related deaths, things like that.

And on the regulation side, it makes it harder– especially if OSHA is regulating on the General Duty Clause, they have a system where you can submit complaints about this under the National Emphasis Program on Heat. But many farmworkers who are undocumented may not want the Federal Government getting involved, may not feel comfortable enough to report any complaints about the working conditions or even complain to it about to their medical providers or anything like that for fear of losing their jobs. It’s a very vulnerable population, for sure.

IRA FLATOW: That’s amazing. We know that our climate crisis is intensifying. So I can imagine we can expect that this will get worse for the workers.

EVA TESFAYE: Yeah. We’re definitely seeing more climate extremes across the US. We had a really bad heat wave that covered a lot of the Midwest and the South last week. Some parts of the Midwest here where I am had heat index temperatures of over 120 degrees. And one thing we’re definitely noticing about the central part of the country is that the heat index is getting higher.

So heat index is the calculation that includes humidity and temperature. So it often is like described as like the feels-like temperature. And it’s important to consider humidity in this story because humidity can really exacerbate the risks that heat poses because it makes it harder for your body to self regulate by sweating. So one thing that we found, working with Climate Central, they found that a large part of the Central US, so the Mississippi River basin, had an average of six degrees increase in heat index since 1950.

So it’s definitely getting hotter, more humid. I did talk to some farm workers who had worked there for longer. And they said every year is different, but overall, some of them said that it does feel like it’s getting worse. And especially with humidity, they do describe not feeling like they’re not able to breathe. Some of them even said that working in Missouri, where it’s super humid, is worse sometimes than working in places like Florida and Texas, where it’s not humid but it’s really, really hot.

IRA FLATOW: Could we see some kind of standardization for worker protections on the federal level?

EVA TESFAYE: Yeah. So in 2021, OSHA announced that it’s going to work on specific regulations for heat. They’re working on a national standard for heat. The problem is that process could take years. We kind of have no idea when that is going to come. But yeah, they are working on that.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. Yeah, you know how slowly bureaucracy moves, right? Is there concern that any OSHA rules, for example, would come into practice just too late for these people?

EVA TESFAYE: Yes. There is concern. And there are calls from different people to speed up this process. United Farm Workers just reissued its call for a national heat standard. Last year, a bill called the Asunción Valdivia Heat Stress, Injury, Illness and Death Prevention Act was introduced. And that would force OSHA to issue a heat standard much faster than the normal process.

That bill didn’t make it anywhere last year. But it has been reintroduced by Democrats this year. So there is this concern. There is this push to try to get this happening faster. Like I said, there was a really bad heat wave last week, and people are waiting for these regulations.

But at the same time, I think there’s also an awareness that, once it is there, it might not be implemented entirely well. There is worry about the amount of inspectors OSHA has to implement these things. But everyone I talk to who advocates for farm workers basically said it’s better to have this than nothing. And states are moving too slow on this.

Like I said, there was only four states that had actual regulations, and we’re not really seeing a push for it on the state level. So they are just waiting for the Federal Government.

IRA FLATOW: Well, Eva, we hope that your great reporting might speed this stuff up. Thank you for taking time to be with us today.

EVA TESFAYE: Thank you.

IRA FLATOW: Eva Tesfaye is a reporter for KCUR and Harvest Public Media based in Kansas City, Missouri. She reported this story with Mónica Cordero at Investigate Midwest.

Copyright © 2023 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Kathleen Davis is a producer and fill-in host at Science Friday, which means she spends her weeks researching, writing, editing, and sometimes talking into a microphone. She’s always eager to talk about freshwater lakes and Coney Island diners.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.