You, Too, Can Be All Thumbs. Or At Least Three.

12:11 minutes

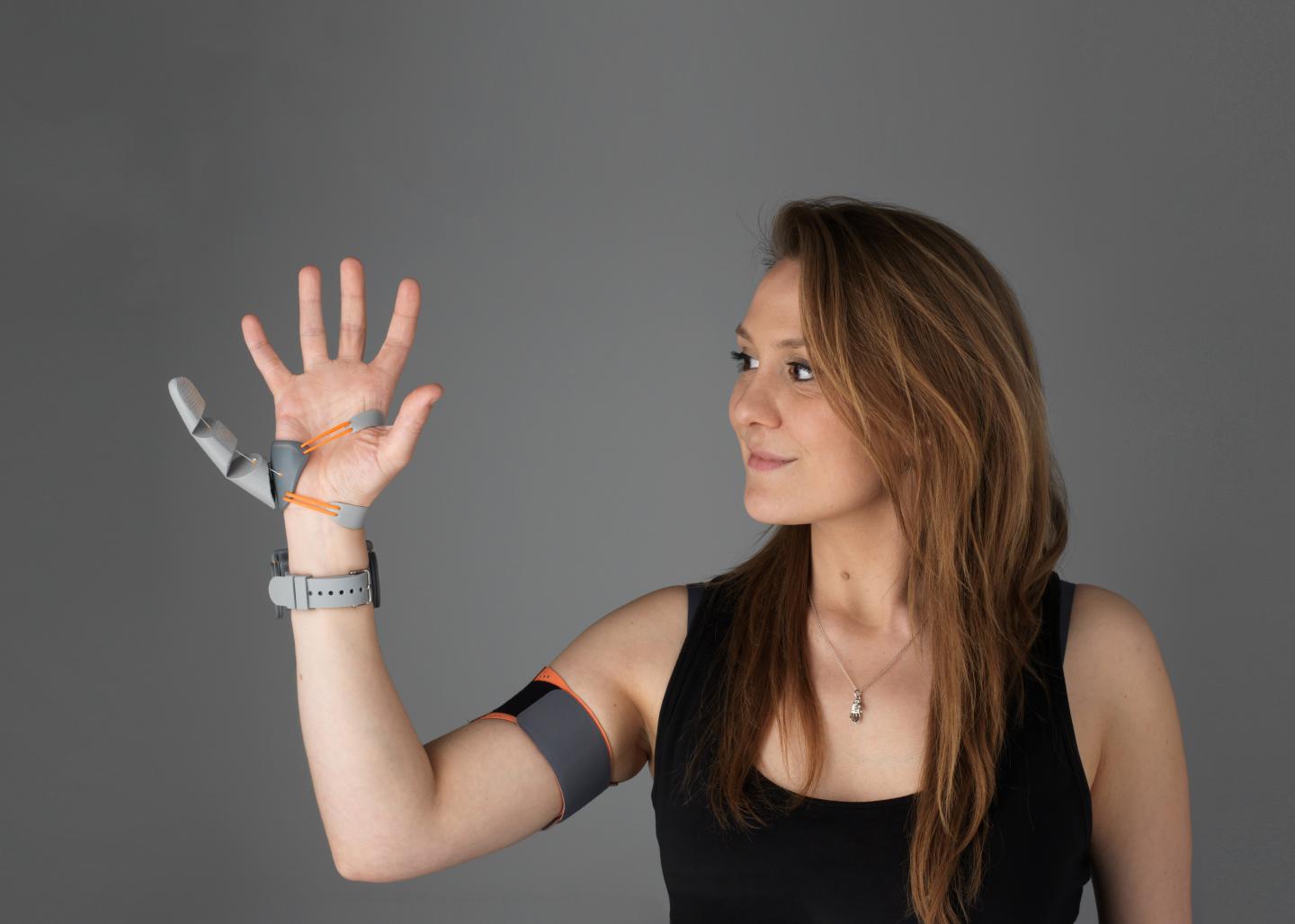

Take a look at your hand and fingers—and imagine that instead of five digits, you had an additional thumb, approximately opposite your natural thumb. Researchers at University College London built what they call the “Third Thumb”—a flexible, 3D-printed prosthetic device, controlled by pressure on sensors under the wearer’s big toes.

The researchers studied how people wearing the thumb adapted their mental models of the world to incorporate their new, augmented body part, which they were able to use to perform tasks that usually take two hands, from picking up multiple wine glasses to plugging a USB cable into an adapter held in the air.

The scientists were interested in learning how the brain adapts to such a change, and whether there’s any mental cost associated with controlling a body part that may not always be there.

SciFri’s Charles Bergquist talks with Dani Clode, the designer of the thumb, and Paulina Kieliba, an engineer working on the project, about what they’ve learned from their interactions with extra body parts. Watch a video of how it works below!

Dani Clode is a designer in the Plasticity Lab at the Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience at University College London in London, England.

Paulina Kieliba is a researcher and engineer in the Plasticity Lab at the Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience at University College London in London, England.

JOHN DANKOSKY: This is Science Friday. I’m John Dankosky, in for Ira Flatow. Later this hour, the psychology of nostalgia and a look at the remarkable culture of orca whales. But first, research looks at extending the capabilities of the human hand. Here, Scifri’s Charles Bergquist. Hi there, Charles.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: Hey, John. Do me a favor and take a look at your hand and fingers for me?

JOHN DANKOSKY: OK.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: Now imagine it went thumb, index, middle, ring, little finger, and then another thumb.

JOHN DANKOSKY: OK. An extra thumb, huh? I don’t know, that could be pretty cool. But are we talking about another human thumb here? Or some kind of prosthetic or a robotic thumb?

CHARLES BERGQUIST: Well, definitely not a fleshy thumb but not quite a robot either. The researchers at University College London are calling their creation the third thumb. It’s flexible, it has three points where it bends, and it’s kind of a mirror image of your first thumb in size and location.

JOHN DANKOSKY: OK, that’s pretty cool. But how exactly would you move this thing?

CHARLES BERGQUIST: Well, the researchers rigged it up so that pressing down on sensors with your big toes sends a signal to the servos and actuators that actually make the thumb move.

JOHN DANKOSKY: I think I’m following you here. I’d be moving my extra thumb with my toes, which sounds– I don’t know– kind of like a piece of interactive art.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: So this did start as a project by a design student. But then she connected with a neuroscience lab that studies brain plasticity, especially in people with arm amputations to put some real science behind this work. I talked with Dani Clode, the designer behind the third thumb, and Paulina Kieliba, an engineer on the project, and started by asking Paulina how easy it was to use.

PAULINA KIELIBA: Surprisingly, they were able to pick it up really quickly. Like on the first day when we just gave them the time, asked them to complete some basic tasks, just the basics of how to use it. They got it really quickly and they used it in their daily life a little bit outside of the training as well.

For sort of more refined motor skills, being able to use the time alone for a little bit more dexterous tasks, they did need a little bit of practice. But the basics of how to use it, how to bend this one direction or the other direction, or pick up a basic object from a table, they got that almost instantly.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: And how proficient do they get? Give me some of the examples of some of the tasks that they were able to complete using this third thumb.

PAULINA KIELIBA: So in the study paradigm during the daily training some of the things that we asked them to do included picking up wine glasses, flipping them upside down, putting them neatly on the table. A lot of things were just picking up multiple objects. The most dexterous task we gave them– and this one not everyone was able to complete– was plugging USB cables into a USB adapter that they had to hold in the air. So this is tricky, even if you just–

CHARLES BERGQUIST: I mean that’s tricky for anyone.

PAULINA KIELIBA: I know. Plugging USB cables is very difficult. And we asked them to do it in the air just with one hand holding it, a USB adapter and plugging the cables. Well, some people managed to do it quite fast. Some people struggled a lot. And some people only managed to do it after five days of training. That was perhaps the most difficult task they did.

Another example, perhaps, would be just stirring the content of a cup with just one hand. So you have to hold it a cup in the air and stir the content with the fingers that are not doing anything else. It was really fun observing them learning how to do it.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: Dani, obviously this is not the ultimate goal. I mean, better drink stirring obviously is useful. But this is not the reason that you did this. Why?

DANI CLODE: Yeah, it’s a good question. I design prosthetic arms as well. I work with Apple and prosthetics and at the core of it I wanted to understand what it was like to control something extra attacked to my body and understand the relationship that forms. That was obviously me in design school wanting to kind of explore.

And it’s been amazing getting to collaborate with the Plasticity Lab and really kind of grounding, this kind of weird thing that I made into serious research, and using it as this kind of catalyst to understand how we can work with augmentation technology in the future. I guess I didn’t really kind of design it with a specific goal in place but more so as a framework to consider in different environments.

I would love to start working with different kind of people in their workplaces and creating a version of the thumb that can help them in their specific careers or jobs. And that’s what’s really we’re finding it’s really about is extending not only the reach of the hand, but kind of having multi-dexterous tasks single-handedly.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: Did either of you wear the extra thumb? And if so, what was it like?

PAULINA KIELIBA: Yeah, we both did.

DANI CLODE: Oh yeah, I wear mine all the time.

[LAUGHING]

Yeah I mean, I specifically designed it to be a right-handed one from the start because I’m left handed. So I wanted to be able to kind of work on it while wearing it. Not so much recently, but I’ve spent a lot of time wearing it at exhibitions and stuff like that. I definitely grow an attachment to it.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: When you’re wearing it, do you have to consciously think about I am now going to bend my bonus thumb in? Or do you just think, I want to hold the coffee cup and stir it, and the mind takes care of that part?

DANI CLODE: It’s funny. I don’t think I consciously felt the shift. But because of the sheer amount of hours I have now spent wearing mine, it’s definitely not something I actively think about. Paulina, did we have a point where the participants stopped kind of overthinking it? I feel like it was like on day two even, they would stop even thinking about pressing down their toes.

PAULINA KIELIBA: Yeah, it differs from participant to participant. Like every person was slightly different, but some of them did tell us that at some point they weren’t thinking about pressing down their toes or like moving the thumb. But they would just sort of start to naturally embed into what they were doing with their hands.

For me, I worried a lot when we were designing the study just to try to figure out what kind of tasks we can give people. What can we ask them to do with this third thumb? And it took me a while. I was one of the people that actually for a longer while I had to think, OK I want to move the extra thumb now. Not so much press down the toes, but I want to move that extra finger I have.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: Do you think there’s a difference in how the brain responds to a prosthetic that’s say replacing a missing body part versus one that’s adding this new body part that they didn’t have before?

PAULINA KIELIBA: I mean, we cannot say for sure, because no one actually carried out such a detailed comparison. But I would guess yes. Because when we’re adding something like a prosthesis that’s supposed to replace a function that we lost, our brain sort of has this let’s say freed up resources that before we’re responding to me moving my natural hand that I may no longer have. But now can be used to control a prosthetic arm or to control something that I’m adding to replace the loss function.

But when we’re talking augmentation, such as third thumb or going bigger, third arm or anything like that, we don’t really have this part of our brain that has been freed up. So we’re adding on top of a fully occupied homunculus, fully occupied cortex. And the brain has to adapt to it in a slightly different way.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: Paulina, you mentioned the possibility of ill effects that this technology could potentially have. What do you mean by that? Tell me more there.

PAULINA KIELIBA: Right. So imagine a day in the future when having third thumb or a third hand is something relatively normal. Let’s say, at a certain sort of work scenario. So for example, you work in a factory, and you’re assembling stuff for the whole day. And your employer gives you this, let’s say, two extra arms to just allow you to work more efficiently, perhaps, and more ergonomically.

But then at the end of the day you need to leave these two extra arms at your work, and you get it back in the car. You drive home, you go home, you make coffee, play with your kids. The question is whether after leaving just two extra hands at work, your brain can still control your two natural hands as well as it did before. Is there no cost to adapting to using four heads? Can you still do everything safely when you’re done off these extra devices?

It’s a question without an answer for now. It’s just a consideration. We have no proof to say that there is a cost. We have no proof to say that there is no cost. It’s a very open question but a very important one, I think, to ask and to try to answer.

DANI CLODE: And I think that that’s when this collaboration that you brought up is going to be absolutely key. Is that this kind of technology doesn’t just get chucked into– especially the workplace– being such a prevalent amount of hours, now a day, and just kind of running without any kind of really hard research into the impact that it’s potentially having.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: I’m thinking of people who are really good with tools, like a carpenter who’s using a hammer all day long. And people have this expression, they say it’s like the hammer becomes an extension of their body. But the tool is still a very distinct thing. You never try to hammer something when you’re not holding a hammer. Is the third thumb like a tool? Or is it like a body part?

PAULINA KIELIBA: Another great question.

[LAUGHING]

There’s a lot of talk about this whole embodying tools or whether tools really become parts of us. But as you mentioned, when you hold a hammer all you really do is you find a grasp that sort of fits the handle of the tool you’re using. And you just hold it, and you either hammer something down or use a screwdriver. But all your hand is really doing is holding that tool for most of it.

Whereas with the third thumb or such augmentative devices, you’re actually changing how your fingers cooperate together. Because in order to use the third thumb, it’s not sufficient that you just find a static hand posture that you maintain. But you need to find a way of integrating the movements of that third thumb with the movements of your natural fingers. They need to work together.

And I think as such, it’s quite different to a sort of traditional tool. Also because again as you mentioned, it doesn’t sort of occupy your hand space. So your hand is still free to grasp to do something else.

DANI CLODE: To hold a tool even.

[LAUGHING]

PAULINA KIELIBA: Or to hold a tool. You could very well hold a hammer and do something else at the same time with one hand.

DANI CLODE: Yeah, it’s an extension of the hand in a way that it’s extending the physical hand rather than extending kind of I guess a specific function. Although these words become really muddled when you start to kind of try to tease them apart between tools and augmentation.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: Did people miss having the thumb once it was gone? Did they find themselves trying to do the coffee cup trick and realizing, oh wait, I can’t anymore?

PAULINA KIELIBA: I’m not sure about the coffee cup drink, but we definitely had a few people that missed it a lot. We had one girl that needed to say goodbye to the thumb on the last day of training when we were taking it from her. We had a couple of people that sort of jokingly refused to give it back.

And we had this one great participant that he came back for another neuroimaging session a week later. And he told us that for this week when he didn’t have the time, he really felt like a part of him was missing, like his hand was different, was perhaps not complete. He got used to having it and to using it so much.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: Dani Clode is the designer and Paulina Kieliba is a researcher and engineer in the Plasticity Lab run by Professor Tamar Makin at University College London. Thank you so much for taking the time to talk with me today.

PAULINA KIELIBA: Thank you very much.

DANI CLODE: Thanks for having us.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: For Science Friday, I’m Charles Bergquist.

Copyright © 2021 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

As Science Friday’s director and senior producer, Charles Bergquist channels the chaos of a live production studio into something sounding like a radio program. Favorite topics include planetary sciences, chemistry, materials, and shiny things with blinking lights.

John Dankosky works with the radio team to create our weekly show, and is helping to build our State of Science Reporting Network. He’s also been a long-time guest host on Science Friday. He and his wife have three cats, thousands of bees, and a yoga studio in the sleepy Northwest hills of Connecticut.