Exposing Texas’ Excess Emissions Problems

12:04 minutes

This story is published in collaboration with Grist. It was supported by the Fund for Investigative Journalism. By Naveena Sadasivam, Clayton Aldern, Jessie Blaeser, and Chad Small, Grist, June 7, 2023.

In the early hours of August 22, 2020, Hurricane Laura was still just a tropical storm off the coast of the Leeward Islands in the Caribbean. But effects from the monstrous storm, which would ultimately take at least 81 lives, were already being felt on the U.S. Gulf Coast.

As rain poured down on the Sweeny refinery in Old Ocean, Texas, that afternoon, two processing units failed, releasing nearly 1,400 pounds of sulfur dioxide, which can cause trouble breathing, and other chemicals.

Over the next few days, Laura siphoned up moisture from the warm waters of the Gulf of Mexico and transformed into a Category 1 hurricane.

In Texas, chemical plants began shutting down, hurriedly burning off unprocessed chemicals and releasing vast amounts of pollution in anticipation of the storm making landfall. On August 24, Motiva’s Port Arthur refinery released 36,000 pounds of sulfur dioxide, hydrogen sulfide, and other noxious pollutants.

The next morning, Motiva began purging chemicals its plant had been processing, emitting nearly 48,000 pounds of carbon monoxide and propylene, among other pollutants. The following day, a Phillips 66 refinery in southwest Louisiana shut down, releasing more than 1,900 pounds of sulfur dioxide.

Then, as gale-force winds swept through coastal communities and the relentless rain poured down, the chemical facilities increasingly malfunctioned.

On August 27, an overflow container at Motiva’s Port Arthur refinery flooded, causing it to spew over 1,700 pounds of pollutants. Across the border in Louisiana, a chemical plant caught fire.

In Texas alone, Hurricane Laura resulted in at least an additional 680,000 pounds of pollution — almost as much as the toxic load carried on the train that derailed in East Palestine, Ohio, earlier this year.

These so-called “excess emissions” — the term of art for intentional and at times inevitable pollution beyond permitted levels — don’t just happen during hurricanes. From petrochemical refineries on the Gulf Coast to oil and gas wells in West Texas, hundreds of polluting facilities routinely emit hundreds of millions more pounds of chemicals into the air than their permits stipulate. The reasons are many: when a plant unexpectedly loses power, or when a customer is suddenly unable to receive the natural gas extracted at a well, or when a valve or pump or any other piece of complex machinery malfunctions.

The resulting pollution contains nitrogen oxides, sulfur oxides, and a slew of carcinogenic chemicals. Companies claim that these emissions are unavoidable. When faced with malfunctions or natural disasters, facilities have no option but to quickly shut down, which forces them to burn off the chemicals they’re processing. It is a necessary evil — or so goes the claim.

Excess emissions inhabit a legal gray area. Court rulings and regulatory decisions by the Environmental Protection Agency, or EPA, in recent years have noted that these emissions are illegal, but the decision to penalize polluters largely lies with state regulatory agencies — who rarely punish companies. Between 2016 and 2022, Texas regulators found that less than 1 percent of these events were actually “excessive,” meaning they prompted corrective action. Texas’ own analysis has found that it pursues penalties and monetary fines in just 8 percent of cases.

The lack of enforcement has left environmental advocates dumbfounded.

“We want the regulators to do their jobs,” said Ilan Levin, an attorney with the nonprofit Environmental Integrity Project. “Whether it’s EPA or Texas, they need to be doing enforcement.”

Over the past year, Grist analyzed a database of industry-reported pollution from the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, or TCEQ, the state’s environmental regulator. We used this information to build a regional timeline of excess emissions over nearly 20 years. By converting disparate chemicals and compounds to a uniform mass measurement — pounds — we were able to estimate the cumulative scale of these highly polluting and unregulated events.

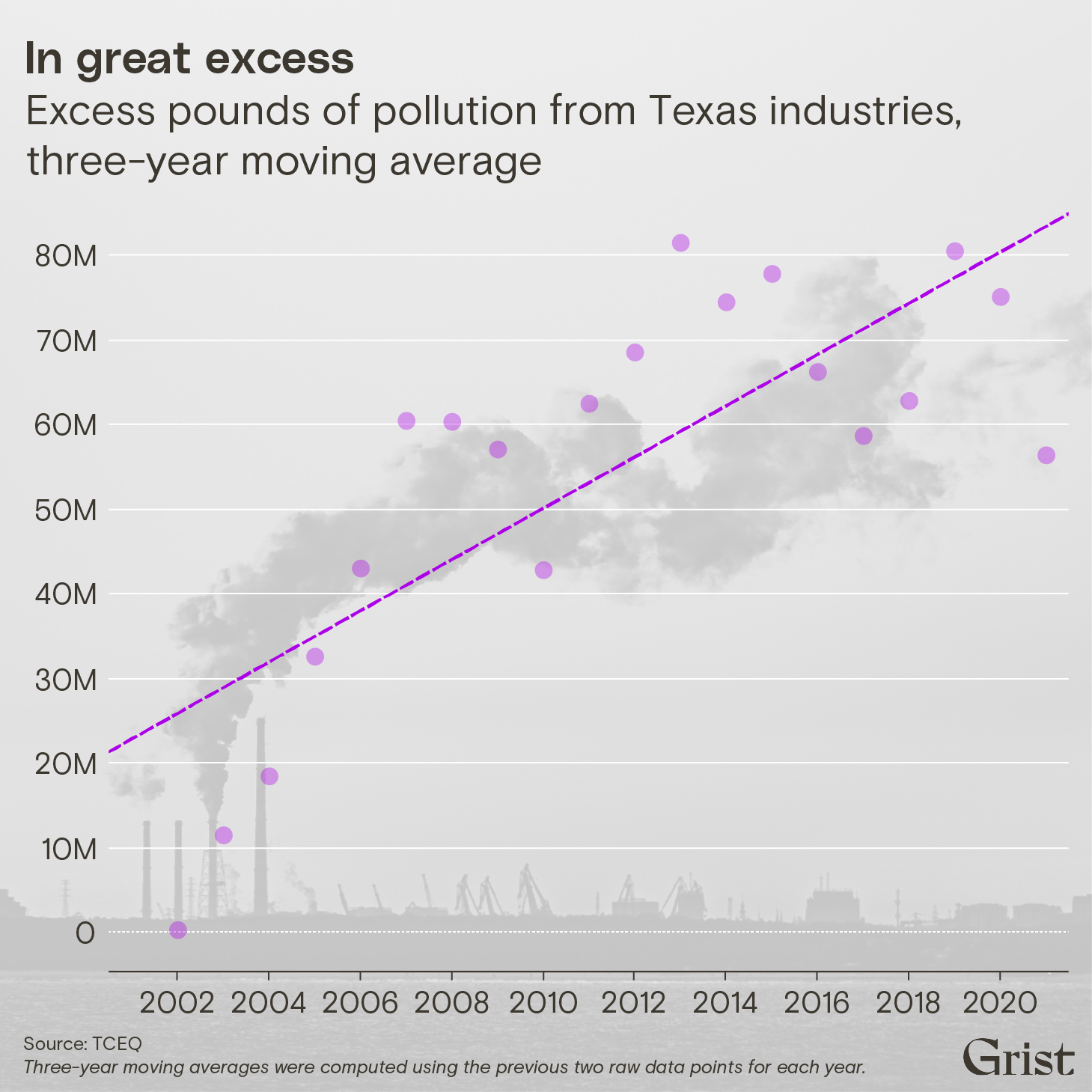

Grist found that companies have released some 1.1 billion pounds of pollution beyond their permit limits since 2002. The vast majority of these emissions occurred along the Gulf Coast and in West Texas, home to the Permian Basin, the largest shale deposit in the nation. As fracking exploded in the West and a petrochemical industrial buildout boomed along the coast, instances of unauthorized pollution grew rapidly over the years: In Texas, the three-year excess emissions average in 2020 was nearly 75 percent higher than it had been in 2006.

Sulfur dioxide and volatile organic compounds, which cause respiratory problems and have been linked to cancer, respectively, make up about half of these emissions. While it’s difficult to tease out the exact health effects these emissions have had on residents nearby, one study found that excess emissions in Texas alone are responsible for an average 35 additional deaths every year.

Laura Lopez, a spokesperson for TCEQ, said that “tremendous” growth in industrial activities in the state account for upward trends in excess emissions, but added that the number of incidents and total emissions decreased significantly during the pandemic years. The agency has conducted meetings, workshops, and web events with industry representatives and increased its rate of enforcement actions to deter noncompliance over the past few years, she said.

For those living close to polluting facilities, the emissions take a toll. Christopher Jones is the president of the South End Charlton-Pollard Greater Historic Community Association in Beaumont, Texas. The neighborhood takes the name of the first supervisor of a local Black high school and a formerly enslaved man who founded the first school for Black children in Beaumont. It sits adjacent to a massive ExxonMobil refinery that suffered significant damage during Hurricane Harvey, ultimately emitting nearly 130,000 pounds of pollutants during the disaster. From 2003 to 2021, it released an additional 22 million pounds of pollutants outside its permit limits — the fifth highest in the state. The facility is just one of many industrial polluters in the town, which is home to a crowded port and crisscrossed by railroad lines. Combined, the industrial facilities in the region are responsible for more than 200 million pounds of excess pollution between 2003 and 2021.

“There’s some mornings when I wake up, and it’s putrid outside,” said Jones. “And it’s hard to tell who or what industry it comes from.”

As climate change brings warmer weather and stronger hurricanes, these events are likely to worsen. In order to statistically model the effect of extreme weather on recent excess emissions, Grist merged the emissions dataset with documented hurricane and tropical storm paths as well as company-reported references to weather causing malfunctions and emissions.

Our models suggest that extreme weather resulted in at least 25 million pounds of excess emissions from 2002 through 2020. Looking at a subset of the emissions data that included geographic information, we found that even low levels of rainfall are linked to increases in emissions.

For a given facility in a given year, a 1 percent increase in precipitation corresponded to a roughly 1.5 percent increase in the mean magnitude of an excess emissions event (equivalent to roughly 45 pounds, all else equal). Similarly, a 1 mile per hour increase in average windspeed was associated with a 0.6 percent increase in emissions magnitude (17 pounds).

While these increases appear small in magnitude, they can add up — especially as tropical storms making landfall in the Gulf states are becoming more extreme due to climate change. A recent analysis by the First Street Foundation, a climate research group, found that a greater percentage of Gulf hurricanes are expected to reach major hurricane status. Another study estimated that a 1 degree Celsius increase in sea-surface temperatures would increase total Atlantic cyclone precipitation over land by 140 percent. In our Texas sample, we estimate that effect would translate to a rough tripling of storm-related excess emissions, all else equal — approximately an additional 52 million pounds over the same time period.

A 2022 Government Accountability Office report found that of 1,357 facilities handling hazardous chemicals in Texas and Louisiana, nearly 70 percent were vulnerable to sea-level rise, flooding, or storm surge — just the sort of events that could trigger facility shutdowns and massive emissions.

The reasons for the stark, two-decade increase in documented excess emissions appear to be multifaceted. Since the Texas legislature in 2001 mandated that facilities quantify and report excess emissions events, companies have slowly grown accustomed to the requirement and more routinely report the events. Development of better monitoring technology over the last two decades may also have led to more accurate pollution estimates.

But the rise of hydraulic fracturing also appears to have played a major role. Beginning around 2008, with oil prices at an all-time high, fossil fuel companies began investing in fracking, unleashing a new trove of shale oil and gas deposits. As oil and natural gas became cheaper over the next decade, petrochemical plants were built out along the Gulf Coast. The amount of crude oil processed on the Texas and Louisiana coasts increased by 40 and 23 percent, respectively, between 2008 and 2018.

“The throughputs at the refineries have really jumped,” said Neil Carman, a former investigator at TCEQ, who now works for the Sierra Club. “There’s huge refinery expansion in Texas and across the U.S.”

These increases in production appear to have caused a corresponding spike in excess emissions, particularly during inclement weather. Our analysis found that during extreme weather events such as winter freezes and floods, average excess emissions in the Permian Basin rose by 32 percent.

Regulators have largely overlooked this pollution, despite a 2008 court ruling declaring that excess emission events during startups, shutdowns, and malfunctions are illegal. As a result of the ruling, the EPA pushed Texas and other states to strengthen its oversight of excess emissions during the Obama presidency, but the Trump administration then rescinded that effort.

More recently, the Biden administration found that the way Texas handles excess emission events does not meet the requirements of the Clean Air Act. The federal government subsequently initiated a yearslong process that is ultimately expected to prevent states from automatically exempting excess emissions events from regulatory scrutiny. However, the states will still maintain enforcement discretion at the end of the day, which means the EPA process might not actually result in penalties for polluters — or fewer emissions.

“You want to have good rules that are very clear and very easy to enforce, but you still need to have a good agency enforcing them,” said Adam Kron, an attorney with the environmental nonprofit Earthjustice.

Lopez, the TCEQ spokesperson, argued that the agency’s enforcement has been appropriately vigorous. Since the implementation of reforms in the 2019 fiscal year, she said, 8 percent of excess emissions events resulted in formal enforcement actions. Whether an excess emissions event is deemed “excessive” and leads to corrective action has also been ticking upward, she added, increasing from 23 to 29 determinations in the last few years. (Those remain a small fraction of the thousands of reports of excess emissions submitted by facilities during that period.)

In addition, Lopez noted that oil and gas companies in the Permian Basin have installed equipment to reduce their emissions. “These activities have improved the reporting of emissions events and driven industry activities to reduce the number of reportable events and the total quantity of unauthorized emissions,” she said.

The polluting companies, for their part, have argued that regulatory exemptions are justified because excess emissions events are unavoidable. But environmental and public health advocates take issue with the suggestion that all 1.1 billion pounds of emissions over the last two decades were necessary or inevitable. With adequate preparation for extreme weather and better operational practices, they argue many of these emissions events could be mitigated or eliminated. For example, companies could invest in backup generators for use during power outages and install fail-safe equipment like vapor recovery units, which collect combustible vapors from storage tanks and prevent emissions from escaping.

An analysis from Public Citizen Texas found that outdated rules are one reason why industrial facilities on the Gulf Coast seem to fail during major storms. State regulations that govern building standards for industrial equipment rely on rainfall estimates from 60 years ago. As a result, they are not built to withstand the more intense rainfall of today. During Hurricane Harvey, for instance, petroleum storage tanks at nine facilities collapsed or otherwise failed, releasing 3.1 million pounds of pollutants into the air and water.

Despite the lax regulations, companies have found additional ways to downplay their emissions. One common tactic companies take is to spread out an emissions event over several days in their paperwork. Facilities do this because they typically have permit limits that place caps on the emissions they can release per hour. But if companies can make the case that the emissions took place over several days — or even months — they’re more likely to be able to stay within permit limits.

Take the Valero refinery in the Houston neighborhood of Manchester. In early 2022, a power outage caused the company to flare a massive amount of chemicals for a couple of hours. Air monitors near the plant showed particulate matter levels spiking. But when the company submitted its official excess emissions event report to the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, it claimed the event had taken place over 15.5 hours. If the company had averaged the emissions over a two-hour period, it would have violated limits for particulate matter, nitrogen oxide, and hydrogen sulfide emissions.

“It’s pretty common to see these extended time spans that don’t really match up with what we’re seeing on the ground and what we’re hearing from people about these events,” said Corey Williams, an environmental consultant who until last year was a research and policy director at Air Alliance Houston.

Representatives for Valero did not respond to a request for comment.

In other cases, routine maintenance events that a company has advance knowledge of — and therefore should count toward permitted emissions limits — are sometimes categorized as excess emissions. Levin, the Environmental Integrity Project attorney, pointed to two common industry practices, blowdowns and pigging, that operators sometimes point to as reasons for excess emissions. (Blowdowns are used to clear natural gas from a pipeline when companies need to perform maintenance on a section of the pipeline, and pigging refers to the use of equipment called “pigs” to perform inspections, repair, and maintenance of pipelines.)

They “are just standard industry practice,” said Levin. “You kind of have to do it. It’s part of operating safely, but they still get reported as though they are ‘oopses’ or accidents or upsets.”

The laissez-faire attitude toward reporting and enforcement leads many residents who live near these operations to take matters into their own hands. One evening in March 2022, Jones was driving back home to Beaumont when he began getting a series of calls from friends and neighbors. The Exxon refinery’s smokestack was pouring thick black smoke while the facility burned an unusually large flare, and they wanted to know if he had any information. One resident thought it was causing her eyes to water, and the back of her throat burned. Others reported feeling unwell.

Jones and many of these neighbors had lived near the refinery for years and were used to seeing big flares go off, lighting up the sky and spewing a toxic cocktail of chemicals and soot. Just a few years before, a fire at a wood pellet company in nearby Port Arthur had burned for 102 days.

But they all agreed that something was different about this Exxon fire. “That’s a big-ass flare,” Jones recalled being told. The flare was so thick that residents in Houston, more than 80 miles away, could see it. Jones went to sleep that night and woke up the next morning only to see that the flare was still going strong.

“It was still black,” Jones recalled. “I went up to it, and I rolled my window down, and I went ‘Oh, it does make your throat burn.’”

When he called Exxon to inquire, he was told that they’d sent out a notification on the Southeast Texas Alerting Network, which is used for emergency management. The network is supposed to alert residents, but Jones said he didn’t receive any notifications on his phone.

The flare was the result of a maintenance event, according to a public announcement by ExxonMobil on its Twitter account, but it has not been reported to TCEQ’s emissions database. ExxonMobil did not answer specific questions about whether the company was required to report the event to TCEQ and why it hasn’t. “We operate under an aggressive state and federal regulatory system, and report emissions to the U.S. EPA and TCEQ in a consistent and timely manner in accordance with all laws, regulations, and permits,” a spokesperson said.

It’s an example of the underreporting that may be taking place. The emissions dataset is only as good as the industry-reported data, and environmental advocates say companies often find ways to downplay their emissions.

“What you’re seeing [in the data] is not everything,” said Carman, the former TCEQ investigator. “There can be bad events at the plants they don’t even know about.”

Naveena Sadasivam is a senior staff writer at Grist, based in Oakland, California.

Clayton Aldern is a senior data reporter at Grist, based in Seattle, Washington.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow.

Did you know that sometimes facilities like refineries and gas wells get a free pass to emit more chemicals than they’re technically allowed to? Yes, it happens for safety reasons like if there’s a hurricane or a fire. And that means releasing massive amounts of chemicals like nitrogen oxides and carbon monoxide into the air all at once.

This is called an excess emission event. And it makes sense, right, to avoid some bigger catastrophe? But you guessed it– that’s not great for climate change or air pollution, and potentially not for people’s health. This week, Grist published an investigation into this, asking, are all these emission events necessary? And are the companies being held responsible for what they emit?

We teamed up with Grist for this story, and joining me now are their two reporters. Naveena Sadasivam is a senior staff writer at Grist, based in Oakland. Clayton Aldern is a senior data reporter at Grist, based in Seattle, Washington.

Welcome, both of you, to Science Friday.

NAVEENA SADASIVAM: Thanks for having us.

CLAYTON ALDERN: Yeah, thank you.

IRA FLATOW: You’re welcome. OK, Naveena, get us started. Tell us what exactly happens during an excess emission event.

NAVEENA SADASIVAM: Sure. So excess emissions basically refers to pollution from chemical facilities that are beyond what’s permitted. So if you operate a chemical facility, the state gives you a permit that defines how much pollution you can release into the air. But they make an exception for certain circumstances.

So if your facility has to shut down or it has to start up or if it malfunctions, you’re allowed to pollute above those limits as long as you report to the state environmental agency that you basically did that and essentially you didn’t have any other option.

IRA FLATOW: I get it. And you start your story talking about Hurricane Laura.

NAVEENA SADASIVAM: Yeah, sure. So when Hurricane Laura began forming in the Atlantic towards the end of August 2020, a number of chemical facilities either began malfunctioning or they decided to shut down. So as they started shutting down, they began purging a lot of the chemicals in their system. And if you look at the reports that they submitted to the state, you’ll see a whole bunch of these emission events.

So on August 24, Motiva’s refinery shuts down. It releases 36,000 pounds of sulfur dioxide, hydrogen sulfide, a bunch of other pollutants. Then, the next day, another Motiva Chemicals facility emits another 48,000 pounds.

A Phillips refinery in Louisiana shuts down. Another chemical plant in Louisiana catches fire. Which, for context, is almost as much as the toxic load that was being carried on the train that derailed in East Palestine, in Ohio, earlier this year.

CLAYTON ALDERN: But in fact, extreme weather isn’t even the majority cause here. Facilities might release pollution in this manner for a variety of reasons. A plant might unexpectedly lose power, or maybe a valve or a pump or some other piece of complex machinery malfunctions. And in all these cases, a polluter might have cause to spit out excess emissions.

IRA FLATOW: And the crux of this story, so I understand it, isn’t just that these big polluting events happen, but they don’t really get counted, right?

NAVEENA SADASIVAM: Yeah, basically that’s right. Since 2002, at least in Texas, companies are supposed to notify the state about these excess emission events within 24 hours of them happening that basically states how much they polluted, for how long, and why it happened. But it’s extremely routine for companies to claim that they had no choice but to pollute.

So even when, in some cases, you could argue that, with better technology or safer shutdown practices, they could have avoided some of these emissions. And the state basically takes them at their word.

One recent analysis found that Texas only labels less than 1% of these cases as “excessive emission events.” So overall, it’s quite rare for companies to face any sort of punishment for using the exemption.

IRA FLATOW: And Clay, I understand you crunched your own numbers for this, right? What did you look into?

CLAYTON ALDERN: Yeah. So using public records requests, we compiled a dataset of about 20 years of excess emissions data. That’s about 300,000 of these events. And all told, it appears excess emissions events between 2002 and 2021 or so, they sum to about 1.1 billion pounds of under-the-radar pollution.

IRA FLATOW: And that has to spell bad news for the people who live near these refineries and breathe in that air. Naveena, tell us what’s happening to them.

NAVEENA SADASIVAM: When I traveled to Texas, I met a gentleman by the name of Christopher Jones. Chris lives in the Charlton-Pollard neighborhood, in Lake Beaumont and is the neighborhood association president. The neighborhood sits right next to this massive ExxonMobil facility, and that whole area is surrounded by industry.

And when I visited, Chris described constantly smelling all sorts of strange smells.

CHRISTOPHER JONES: But there are some mornings when I wake up and it’s putrid outside. And it’s hard to tell who or what industry it comes from.

NAVEENA SADASIVAM: Yeah. And he told me, last year, he was driving back to Beaumont one day, and his phone just started blowing up. He started getting a series of calls from his friends and neighbors about a massive flare at the Exxon refinery. And one resident told him her eyes were watering, and others were telling him they were feeling unwell.

And many of these neighbors had lived in that area for a really long time, but they described this particular flare as different. They were saying, it’s spewing this very thick black plume and it didn’t look like anything that they had seen before.

So the next morning, Chris then told me he drove to Exxon just to see this for himself.

CHRISTOPHER JONES: It was still black. And I rolled my window down and I said, oh, it do make your throat burn.

NAVEENA SADASIVAM: Exxon has basically posted on its social media that it was conducting maintenance that day, and the event was not reported to the Texas Excess Emissions Database. I reached out to Exxon with questions, and the Exxon spokesperson said that the company “operates under an aggressive state and federal regulatory system and reports emissions to the US EPA and the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality in a consistent and timely manner, in accordance with all laws, regulations, and permits.”

IRA FLATOW: You speak of all laws, regulations, and permits. What about the Clean Air Act and the EPA? Is there no protection afforded by them?

NAVEENA SADASIVAM: Yeah, that’s a great question. This has been a longstanding problem. And the EPA, depending on the administration, has gone back and forth on how to regulate these excess emission events. So in 2008, a court basically ruled that the exemption for excess emission events during these startups, shutdowns, malfunctions, that it’s basically illegal and not in line with the Clean Air Act.

So during the Obama administration, the EPA basically said Texas wasn’t allowed to use this particular exemption. But then, of course, President Trump took office, and that decision was reversed. And now, earlier this year, the Biden administration has basically reversed that reversal.

And both Texas and Louisiana have to come up with a new plan for overseeing chemical facilities without allowing them to use these exemptions. It will probably take a couple of years for the new plan to take effect. So in the meantime, companies continue to use this exemption.

IRA FLATOW: And so this is a potentially dangerous cycle to be stuck in. I mean, you have climate change making storms worse, so refineries release more emissions. And that’s certainly not helping climate change, right?

CLAYTON ALDERN: Yeah. Yeah, that’s right. We work to isolate the effects of extreme weather on the types of events we’re talking about here. And our statistical model says that, for a given facility in a given year, basically, a 1% increase in precipitation corresponded to roughly a 1.5% increase in the mean magnitude of an excess emissions event.

And we also extrapolated from a recent study of sea surface temperatures and precipitation intensity. And given that study, we can estimate that about a 1 degree Celsius rise in temperature in our dataset would have led to about 52 million pounds of excess emissions. And 70% of chemical facilities are in vulnerable areas.

IRA FLATOW: Well, that’s not great to hear. Naveena, how necessary is it to release emissions when there’s an emergency like a hurricane? I mean, is it avoidable?

NAVEENA SADASIVAM: There are certainly some emergencies when excess emission events are just completely unavoidable. Even environmental and public health advocates will tell you that these excess emission events are sometimes acceptable in cases, because it means the facility can operate safely and it is the least harmful approach in those situations.

But the reality here is that those are not the only situations when facilities are making use of this exemption. So for instance, if you need to shut down a massive facility before, let’s say, a hurricane, you can reduce the amount of emissions you have to release by doing it slowly and over a longer period of time.

But instead, what you actually see happening is facilities will often shut down three or four days before a hurricane makes landfall. And they keep the facility running as long as they possibly can. And then they quickly shut down, just flaring and burning off most of the chemicals in the system. And that is basically an attempt to maximize profits.

And then the other thing also is that, even with these exemptions, companies are still routinely trying to downplay their emissions.

IRA FLATOW: What do you mean by that? How is that?

CLAYTON ALDERN: Take the Valero refinery in the Houston neighborhood of Manchester. So in early 2022, a power outage caused the company to flare a massive amount of chemicals for a couple of hours. And air monitors near the plant showed particulate matter levels spiking. But when the company submitted its official Excess Emissions Event Report to the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, it claimed the event had taken place over 15 and 1/2 hours.

If instead the company had averaged the emissions over a two-hour period, it would have violated limits for particulate matter and nitrogen oxide and hydrogen sulfide emissions.

IRA FLATOW: Amazing. OK, Naveena, so what happens now? Is there a solution– I mean, apart from better regulations, I assume?

NAVEENA SADASIVAM: Yeah, better regulations, but also better enforcement of the regulations will make a big difference I think. Because, like I said earlier, Texas rarely pursues cases against polluters. I did reach out to the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality to get their response to some of our findings. And they pointed out that they have made great strides in reducing excess emission events.

In fact, they told me, in the last few years, during the pandemic, emissions have dropped significantly. They attributed this to a series of interventions they’ve made, including conducting meetings, workshops, web events with the industry, and initiating enforcement action to deter non-compliance.

But what is important to also remember here is that emissions basically fell across the board the last few years during the pandemic as businesses shut down or they otherwise adjusted their operations.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. A lot to think about here. I want to thank both of you for bringing us this story.

NAVEENA SADASIVAM: Thanks so much for having us.

CLAYTON ALDERN: Yeah, thank you, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: Naveena Sadasivam, senior staff writer at Grist, based in Oakland, California. Clayton Aldern is a senior data reporter at Grist, based in Seattle, Washington. And if you want to read the full story, head to our website, sciencefriday.com/emissions.

Copyright © 2023 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Rasha Aridi is a producer for Science Friday and the inaugural Outrider/Burroughs Wellcome Fund Fellow. She loves stories about weird critters, science adventures, and the intersection of science and history.

John Dankosky works with the radio team to create our weekly show, and is helping to build our State of Science Reporting Network. He’s also been a long-time guest host on Science Friday. He and his wife have three cats, thousands of bees, and a yoga studio in the sleepy Northwest hills of Connecticut.