Allergy Season Is Blooming With Climate Change

9:07 minutes

Spring is in the air, and for many people that means allergy season is rearing its ugly head. If it feels like your allergies have recently gotten worse, there’s now data to back that up.

New research shows that since 1990, pollen season in North America has grown by 20 days and gotten 20% more intense, with the greatest increases in Texas and the Midwest. This is because climate change is triggering plants’ internal timing to produce pollen earlier and earlier. It’s a problem that’s expected to get worse.

SciFri producer Kathleen Davis speaks with William Anderegg, assistant professor at the University of Utah’s School of Biological Sciences about pollen counts, and pollen as a respiratory irritant.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

William Anderegg is an assistant professor in the University of Utah School of Biological Sciences in Salt Lake City, Utah.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow.

[SNEEZING]

Oh, gesundheit. You know, I usually don’t start a segment with a sneeze, but spring is in the air and our resident allergies sneezer Kathleen Davis is reminding us that, well, it’s here. Welcome, Kathleen.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Yeah, sorry to sneeze in everybody’s ear.

IRA FLATOW: No problem. I understand you’ve had a really bad allergy season this year, right.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Yes, as you may have heard just now, I’ve been having a really rough time, Ira. I wake up every morning, and I am all stuffed up. My sneezing is just out of control. I go through so much tissue paper, it is honestly disgusting. I will spare you the details because I don’t think you want to know how much I’ve gone through.

IRA FLATOW: Please.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: It’s really brutal. I really think that the past few years have been extra bad allergy wise for me.

IRA FLATOW: And I understand that in between sneezes, you’ve discovered that there’s evidence to back up that recent bad allergy season, right.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Yeah. So there’s new research that says not only is the amount of pollen growing every allergy season, but the season is actually getting longer. It’s not even just recent. This has been the trend over the past 30 years.

IRA FLATOW: Oh, man, that’s bad news for we allergy sufferers. Why is this happening?

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Well, I talked to the lead researcher of this study whose name is Dr. William Anderegg. He is assistant professor of biological sciences at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, and he says this is happening because of something that seems to be dictating a lot of changes to our planet, climate change.

WILLIAM ANDEREGG: We’ve known for a long time that plants are really sensitive to temperature, and when you grow plants that are really controlled environment like a greenhouse and you turn up the temperature or you increase the carbon dioxide in the air, plants tend to grow bigger, and they tend to produce a lot more pollen. They also tend to shift their flowering seasons to start to flower earlier in the year.

And so in our study, we really tried to ask do we see the same responses across the entire swath of the US and parts of Canada. And the short answer is yes. We see that in general plants are starting to flower a lot earlier, and pollen levels start a lot earlier. Pollen seasons are getting longer, and the amount of pollen in the air is going up quite a bit.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: And just how much longer and how much more intense are we talking about?

WILLIAM ANDEREGG: So since the pollen data really started in the 1990s, pollen seasons now are starting about three weeks earlier compared to the 1990s. And there’s about 20% more pollen in the air on average over a year. So a pretty substantial increase in pollen severity as well.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Yeah, that seems like bad news for those of us who are allergy sufferers.

WILLIAM ANDEREGG: Yeah, it’s not great news. Obviously, pollen is a major contributor to allergies to asthma to a lot of respiratory health conditions.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: And just how much was climate change responsible for these changes in pollen?

WILLIAM ANDEREGG: Climate change is playing a very large role in the patterns we thought. By our estimates, it’s responsible for more than half of the change and the lengthening of pollen seasons and pollen season starting earlier and playing a more moderate role in the levels of pollen in the air.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Do we have any idea what could be responsible for the other percentages?

WILLIAM ANDEREGG: There are a number of possible things that might be influencing the other patterns that aren’t explained by climate change. We looked at some of the major potential ones like changes in urban vegetation and didn’t see much there in terms of patterns, but we know that plants and vegetation are shifting across the country both in response to human land use and more subtle changes in climate like species moving northward. So there’s really a lot of possibilities there, and it’s going to take more research to tease that apart.

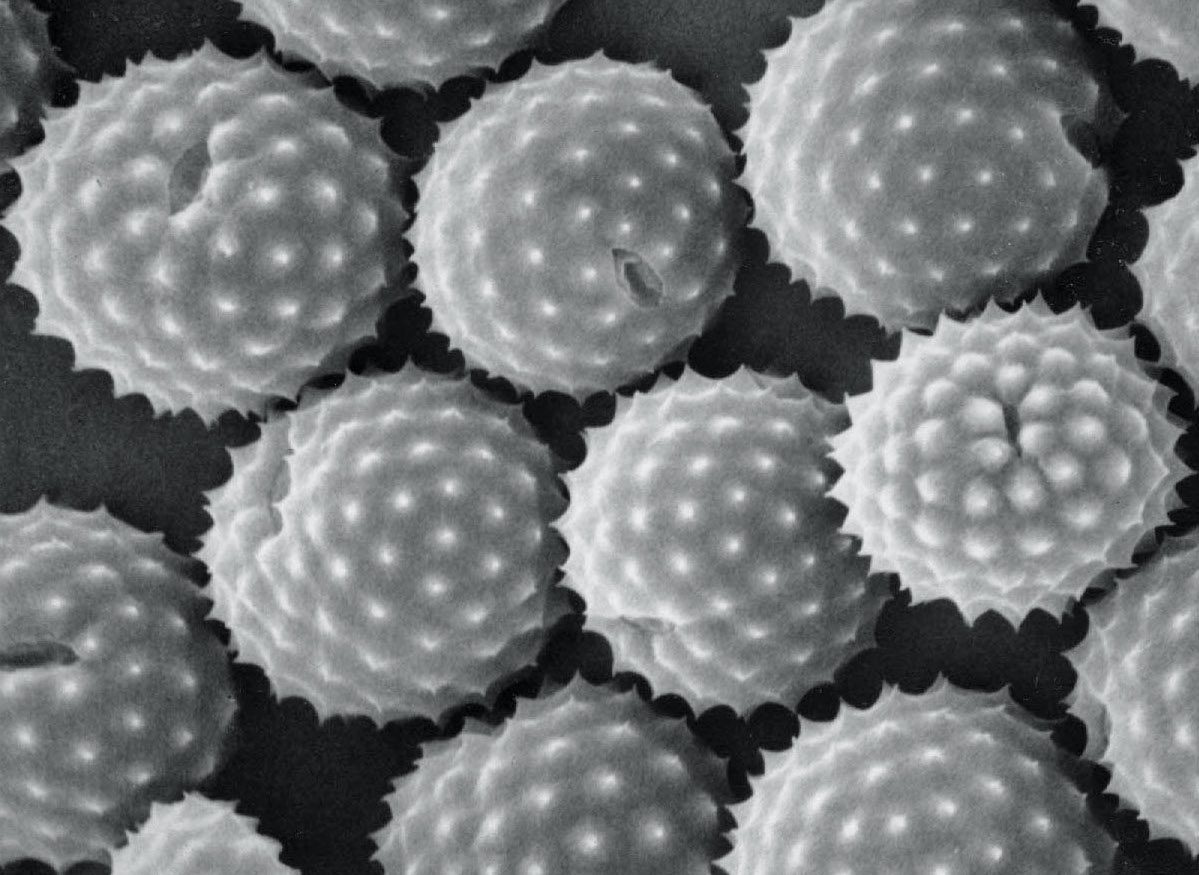

KATHLEEN DAVIS: So what kind of plants are we actually talking about here that are releasing their pollen earlier in the year?

WILLIAM ANDEREGG: There’s certainly a signal across lots of different species of plants. We saw that some of the really high allergy producing plants like ragweeds and other weeds were pretty large contributors that the largest contributors in our data set were actually a lot of tree pollen. So we saw a lot of increases in tree pollen in earlier springs in tree pollen in our data set.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: And what’s actually happening in the plant that is causing this change in pollen release?

WILLIAM ANDEREGG: Yeah, scientists have studied the physiology that leads to pollen production for a while, and we know from these very controlled greenhouse settings that when you either turn up the temperature or increase carbon dioxide, a couple of different effects happen in terms of plant physiology. First, plants tend to grow bigger. They grow more mass.

They also seemed to make these decisions to allocate more of their mass and their carbon to reproduction and to pollen. So they and to grow larger flowers, and individual flowers tend to produce more pollen. So they’re responding in these ways. It’s almost like, well, the conditions seem favorable. I’m going to put out a lot more pollen to reproduce more. So that’s some of the physiological changes that have been documented in these controlled studies.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Now I know that you were looking at North America generally in this study, but I’m curious if you saw any sort of differences regionally in terms of areas that maybe got a little bit more pollen than others or any sort of trends like that.

WILLIAM ANDEREGG: We did see pretty substantial differences regionally. So across the country pollen seasons are getting longer and pollen levels are going up. But the largest increases really tended to be in the Midwest, in Texas, and across the Southeast. Those were the pollen increase hot spots in our study.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: And as you mentioned, you looked at 30 years of data for this study. Can we expect that this trend is going to continue?

WILLIAM ANDEREGG: In the short term, I think we do expect that this trend is going to continue. The driver’s temperature was the largest driver by far across all of these pollen stations, and temperatures are continuing to go up due to human caused climate change. And so at least in the short term, I think we– the next couple decades, we very much expect a continuing trend.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Now we know that pollen impacts the respiratory system. What’s the implication of having a pollen season that just keeps growing?

WILLIAM ANDEREGG: So pollen season that keeps growing means we’re going to expose a lot more people to these higher pollen levels and for longer in the year. And I’ve spoken to several allergists about some of the trends in this, and what allergies have often seen is when pollen seasons start earlier, sometimes their patients are really not prepared and don’t have the medications ready and don’t have a lot of their responses ready. And they’re taken by surprise and then often end up with very severe health consequences.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Now we are in the middle of a respiratory pandemic right now obviously. Do we have any idea how pollen might interact with COVID-19?

WILLIAM ANDEREGG: We have some preliminary ideas, and actually a study just came out this week that has found some links, some correlations anyway, between pollen in the air and the infection rate in COVID itself. So it looks like when the higher pollen levels are in the air, the infection rate of COVID goes up. This was a study done across 31 countries that just came out a few days ago.

And we know from another earlier study that actually when your lungs and your respiratory tract is already inflamed that this tends to make us more vulnerable to other types of viruses like a lot of the viruses that cause the common cold.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: We hear a lot about certain pollutants that are constantly being monitored at thousands of stations across the US. I’m thinking in particular of PM 2.5, for example. Do you think that we talk enough about pollen as an irritant?

WILLIAM ANDEREGG: I think one of the striking things that I am always a little stunned by actually in doing this research is that we don’t really monitor pollen nearly to the scale that we monitor most of these other airborne pollutants, and our study, which is one of the largest and most comprehensive in terms of number of stations and scales to date was only able to really look at 60 long-term stations whereas we have thousands of air pollution stations in many states. So there’s really I think a lot more that needs to be done to improve our monitoring of pollen levels.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Well, this has been informative. Thank you so much for joining us. Dr. William Anderegg is an assistant professor at the University of Utah School of Biological Sciences in Salt Lake City. Thanks so much for joining us.

WILLIAM ANDEREGG: Thank you

IRA FLATOW: Thanks a SciFri producer Kathleen Davis for bringing us that story.

Copyright © 2021 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Kathleen Davis is a producer and fill-in host at Science Friday, which means she spends her weeks researching, writing, editing, and sometimes talking into a microphone. She’s always eager to talk about freshwater lakes and Coney Island diners.