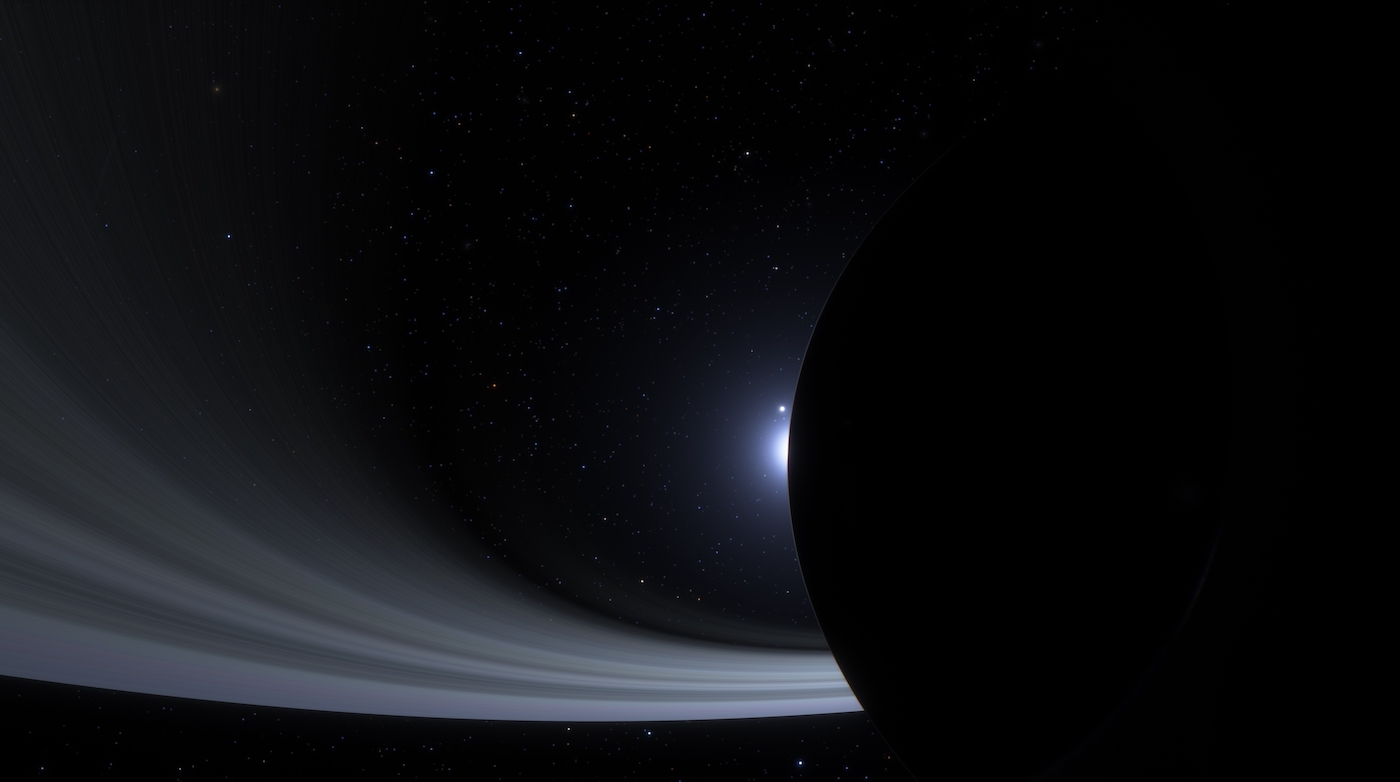

Earth May Once Have Had A Ring Like Saturn

12:15 minutes

Hundreds of millions of years ago, Earth may have looked quite different when viewed from space: Scientists propose it may have had a Saturn-like ring, made up of lots of smaller asteroids.

The new paper, published in Earth and Planetary Science Letters, proposes that this ring formed around 466 million years ago. A major source of evidence is a band of impact craters near the equator. The researchers also posit the ring would have shaded this equatorial area, possibly changing global temperatures and creating an icehouse period.

Ira speaks to Rachel Feltman, host of the Popular Science podcast “The Weirdest Thing I Learned This Week,” about this and other top science stories of the week, including how lizards use bubbles to “scuba dive” underwater, and ancient cave art that possibly shows a long-extinct species.

Rachel Feltman is a freelance science communicator who hosts “The Weirdest Thing I Learned This Week” for Popular Science, where she served as Executive Editor until 2022. She’s also the host of Scientific American’s show “Science Quickly.” Her debut book Been There, Done That: A Rousing History of Sex is on sale now.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. A bit later in the hour, a conversation with the surgeon general, Vivek Murthy, about the stress of parenting. And why, also, is it useful to have AI looking at grains of sand? We’ll tell you later.

But first, black holes. You know, we talk a lot about them on the show because they are so fascinating and mysterious, and the mystery continues. A new study in the journal Nature has found a black hole blasting a massive jet that’s 23 million light years long. That is quite long. Joining me to talk about this and other top science stories of the week is Rachel Feltman, host of the popular science podcast The Weirdest Thing I Learned This Week based in New York. Welcome back.

RACHEL FELTMAN: Thanks for having me, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: All right, let’s talk about this black hole. First of all, what is a black hole jet? Fill us in on that.

RACHEL FELTMAN: Yeah, so in black holes of pretty much every size, something interesting can happen around the inner edge of the accretion disk. Basically, a little bit of material that is getting pulled towards the black hole can suddenly just blast out through these jets that stream out in opposite directions. And they fire out particles at close to the speed of light. So they’re super interesting parts of the black hole landscape.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. And we’re talking about big numbers here, right? 23 million light years. Can you give us some way of digesting that number?

RACHEL FELTMAN: I can. That is the equivalent of lining up 140 Milky Way galaxies back to back, so–

IRA FLATOW: Wow. [LAUGHS]

RACHEL FELTMAN: –pretty big. [LAUGHS]

IRA FLATOW: And how did they detect this?

RACHEL FELTMAN: Yeah, so they found this with the Low-Frequency Array, or LOFAR, radio telescope. This is a European instrument. It’s been doing a sky survey. And it’s actually found more than 10,000 of these megastructures, though this is, of course, a pretty superlative one.

But one thing that’s really exciting is that LOFAR is doing a sky survey, like I said. And they’ve only actually surveyed about an eighth of the sky so far. So it’s possible they’ll find one that’s even bigger.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. Wow. OK, so how does this discovery change what we know about black holes?

RACHEL FELTMAN: So I think there’s still a lot of research to be done to figure out exactly what we can learn from this object. But scientists are really excited because it’s not just the biggest one we’ve seen. It’s also quite old. It’s 7.5 billion light years away, which means it’s 6.3 billion years old.

So it’s from when the universe was like half of its current age. And they’re really interested in seeing how these jets might have contributed to the formation and development and shaping of early galaxies. So it’s a really exciting avenue to go down.

IRA FLATOW: That is cool. Speaking of something else cool, another story about our planet, it turns out Earth used to look quite a bit different. It may have had a ring around it, like Saturn?

RACHEL FELTMAN: Yeah. So this theoretical ring, it would have formed 466 million years ago. And basically, experts are saying a gigantic asteroid could have been tugged apart by Earth’s tidal forces and left behind all of this debris that formed a ring that, for some amount of time, circled around Earth.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. So we had lots of tiny asteroids in the ring? And what’s the evidence for this?

RACHEL FELTMAN: So the evidence is– it’s really interesting because the researchers were trying to explain this period in Earth’s history that was 485 million to 443 million years ago, when we know that there were a lot of meteorite impacts. It was a really tumultuous time on Earth.

So they decided to look at 21 impact craters from that time. And they were seeing that they were all really close to the Earth’s equator. And that was just statistically very unlikely. And they calculated how unlikely, and they said it was the same probability as tossing a three-sided die 21 times and getting the same outcome all 21 times. So–

IRA FLATOW: Wow.

RACHEL FELTMAN: –that made–

IRA FLATOW: Wow.

RACHEL FELTMAN: –them think the more likely explanation was that the reason all these meteorites fell around the equator was that they were in orbit around the equator. So that’s sort of how they reverse engineered this.

And one interesting thing is that this was also a very cold period in Earth’s history. And a ring could have blocked enough sun to explain that cooling. So while we need more evidence to be confident that Earth had this little fashion accessory, it does neatly explain some weird things about that period.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, well, the ring went away by all the stuff falling to earth, so–

RACHEL FELTMAN: Exactly, yeah.

IRA FLATOW: –that explains– yeah. All right, one more space story before we come back to terra firma. And this is just as wild as your first. We’re getting another moon, a mini moon for a couple of months? Tell us about this.

RACHEL FELTMAN: Yeah, a mini moon. Don’t tell the main moon. It might get jealous.

But, yeah, occasionally, something will get pulled into Earth’s orbit. Obviously, lots of things are already in orbit because we’ve put them there. Lots of things come close to earth without actually formally orbiting us because they are just orbiting the sun, as we do as well. But every once in a while, something gets pulled into our gravity and circles around us for long enough that it’s something called a mini moon. It’s just a little temporary moon.

And scientists say we’re getting another one from September 29 to November 25. It was spotted by the Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System, so those guys who are keeping an eye out for asteroids that get too close for comfort. And in tracking this one’s orbit and determining its trajectory, they said it will make a sort of horseshoe orbit around Earth and then return to orbit around the sun, though it’ll actually come back to orbit us again in 2055.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. Is this an uncommon or a common thing to happen? Because we’ve never heard about it.

RACHEL FELTMAN: So we have had mini moons before. There was one that orbited Earth for a few years before leaving again in 2020. There was another object that became a mini moon of Earth in 1981 and 2022 and will come back again in 2051. So it’s not something that happens every day, but it’s not super uncommon.

And a lot of these objects are really small. This one is too small for hobbyists to see in their backyard. But people with larger telescopes will be able to spot it. So if people keep an eye out on NASA or their local university, they might be able to see some cool images of it.

IRA FLATOW: Just too bad. All right, let’s get back closer to Earth and about some– speaking of rocks, some old rock art. A mysterious animal was discovered in South African rock art from a few hundred years ago. Why is this important?

RACHEL FELTMAN: Yeah, so this is important because it’s a great reminder of the stories we tell about natural history and how science works and who we give credit for discovering fossils and looking at them. Basically, we’re looking at some rock art done by the San people of South Africa between 1821 and 1835. There are a bunch of figures painted, and this is a portion of it called the horned serpent panel.

And one of the figures on it has defied identification for a while. It’s this very long-bodied animal. It has these tusks that turn downward. And it doesn’t match any modern species that we know of in the area.

But researchers have noted that there’s evidence that the San people collected fossils and incorporated them into their art. So now researchers are saying this kind of animal that is known to be very abundant and have a lot of well-preserved fossils in this area, the Karoo Basin of South Africa, these animals called dicynodonts, they are saying they’re a really good match.

And the reason that’s interesting is that they went extinct long ago, before the dinosaurs. But we know that there are a lot of well-preserved fossils of them in the area. And we also know that Western scientific descriptions of these animals didn’t come out until 1845. So that’s 10 years after the latest possible date of these cave paintings.

So essentially, researchers are saying that these Indigenous people were collecting fossils and creating illustrations of these animals, these long-extinct animals, before European scientists came and did the same. And it’s just adding to this growing body of evidence that there was extensive Indigenous knowledge of paleontology that has been really poorly understood, particularly in this region of Africa, and that we have a lot to learn about what these people were learning before any colonial influence came in.

IRA FLATOW: That is fascinating, fascinating. All right, let’s talk about animals that exist today. And I’m looking at seabirds, new information about their beaks. Tell us, please, yeah.

RACHEL FELTMAN: Well, so we already know that some birds, like ducks, use their beaks really similar to the way that we humans use our hands. They have a lot of sensitivity in parts of their beaks. And so they’re able to have these very touch-sensitive areas that help them find food.

But we don’t really know how common this is in the larger world of birds. And so researchers decided to look at this large and poorly studied group of seabirds that includes albatrosses and penguins. They’re especially interested because so many of the birds in that group are endangered, and understanding how they look for food could be an important way to help conserve them.

And when they looked at 361 modern bird species, they found that albatrosses and penguins do indeed have these very dense sensory receptors and high concentrations of nerves in their beaks. So they’re doing this tactile foraging that we didn’t know that seabirds could do.

IRA FLATOW: That is cool. All right, let’s stay with our animal theme today and talk about lizards, lizards making their own scuba diving gear from bubbles. OK, you got my attention on this one.

RACHEL FELTMAN: I absolutely love this one, Ira. So we’ve known for a while– or researchers have known. I didn’t know this. Researchers have known that these semi-aquatic lizards called water anoles have this trick where they dive underwater to escape predators. One of the researchers said that these guys are like the chicken nuggets of the forest. Everything wants to eat them. So they very frequently have to dive under the water to escape predators.

And something that happens when they do that is that these little bubbles form on top of their heads. So we knew about the bubbles, but scientists weren’t sure whether they had a function. And so in this very clever study, researchers basically put an emollient on the lizards’ skin to make it less hydrophobic so that air wouldn’t stick to it so the bubble wouldn’t form.

And so then they were able to compare how long the lizards stayed underwater with the bubbles and without. And they found that, actually, the bubble really helps them breathe underwater. It’s serving as a little scuba helmet. And this is how they’re able to stay underwater to avoid predators for 20 minutes or more.

IRA FLATOW: 20 minutes or more little scuba diving– that is terrific. Rachel, always happy to have you on the show. You bring such great stuff with you.

RACHEL FELTMAN: Thanks, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: Rachel Feltman, host of the popular science podcast The Weirdest Thing I Learned This Week. She’s based in New York.

Copyright © 2024 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Kathleen Davis is a producer and fill-in host at Science Friday, which means she spends her weeks researching, writing, editing, and sometimes talking into a microphone. She’s always eager to talk about freshwater lakes and Coney Island diners.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.