Food Pantry Venison May Contain Lead

6:26 minutes

This article is part of The State of Science, a series featuring science stories from public radio stations across the United States. This story, by Samantha Horton and Jared Strong, was originally published by KCUR.

A walk-in freezer about two stories high sits in one corner of a warehouse owned by a food bank called Hawkeye Area Community Action Program Inc. in Hiawatha, Iowa. Chris Ackman, the food bank’s communication manager, points to the shelving racks where any donated venison the organization receives is typically stored.

Known as the Help Us Stop Hunger, or HUSH, program, the venison is donated by hunters from around the state, and Ackman says the two-pound tubes of ground meat go pretty quickly, lasting only a few months.

“It’s a pretty critical program, I think, because there are a lot of hunters in Iowa,” he said. “And, it’s well enjoyed by a lot of families as well.”

Similar programs around the country have been applauded as a way for hunters to do something they enjoy while also helping feed those in need. Iowa hunters donate around 3,500 deer a year through the program. From the hunters, the deer goes to a meat locker, where it’s ground, packaged and shipped off to food pantries around the state. But before it hits the shelves, Iowa officials require a warning label on the venison package.

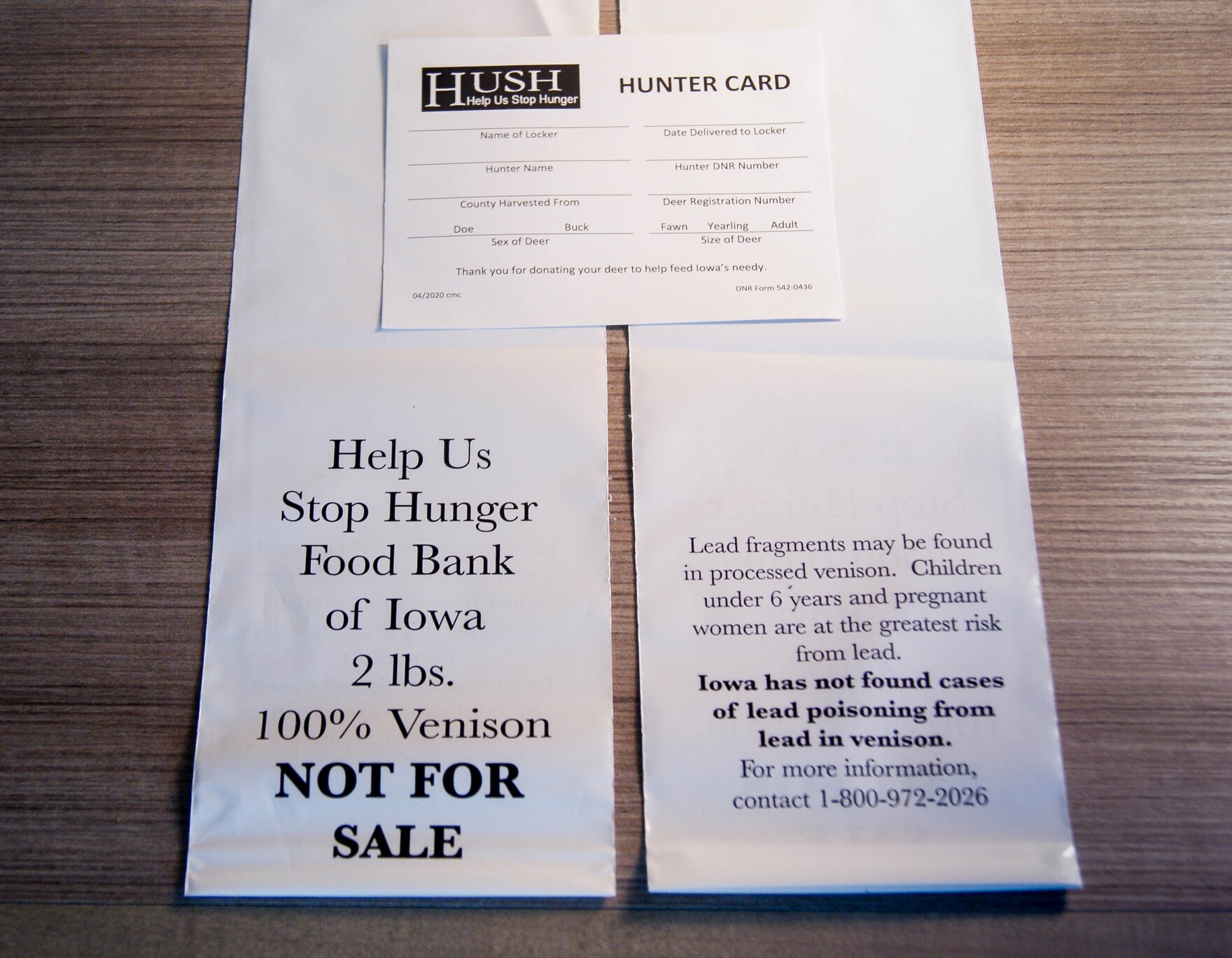

The label reads:

“Lead fragments may be found in processed venison. Children under 6 years and pregnant women are at the greatest risk from lead.”

Then, in bold type, the label notes: “Iowa has not found cases of lead poisoning from lead in venison,” along with a number to call for more information.

Iowa stands out among Midwestern states in requiring a label warning about the potential hazard of lead ammunition and the fragments it can leave behind in shot-harvested game meat like venison. Donated venison in Kansas, Missouri and Nebraska come with no similar warning label.

But concerns have increased in recent years about potential lead exposure in donated venison, as the few studies conducted have shown lead bullet fragments increase the risk of contamination. In Minnesota, health officials began X-raying all donated venison looking for lead more than a decade ago. It’s a process that results in about 10% of all donated meat being discarded.

Lead paint and lead pipes are cited as the top risks of lead exposure to children. But as the pandemic has increased many families’ reliance on food pantries, it’s also raised the profile of lead in donated meat.

“If that’s the most frequent protein that they have, that’s probably what they’re going to go for. And we know that food pantries have been struggling with having good protein products,” said Angela Anandappa, president of the food safety nonprofit Alliance for Advanced Sanitation.

For lower-income families, donated venison could be one of the few affordable proteins available, Anandappa said. “So a matter of prevalence simply exists there in this area,” she said. “So, are we being just to our low income brethren? I think that’s questionable here.”

The pandemic led to more people turning to food pantries for help. Feeding America estimates that more than 38 million people are food insecure. Of that, one in six are children.

The rates of children’s food insecurity in four Midwestern states track closely with national figures:

And while food pantries are facing a higher demand, food banks like Hawkeye Area Community Action Program are struggling to keep up with the donations to meet the need in the communities it serves.

“Our shelves are a lot more bare than they have ever been,” Ackman said. ”So especially on those items that are high protein items, those are items that get hit pretty hard when it comes to inflation.”

The five states listed for the highest donations include Iowa and Missouri, which together account for 8,500 hunted deer donated to food pantries each year. In Kansas and Nebraska, the average yearly total donated is less than 1,000.

Human health concerns over lead-tainted venison were first raised in a 2008 North Dakota study, which found that out of 100 packages of donated venison, more than half contained some lead. The state conducted a follow-up study the next year that found about 6% of the 400 venison packages tested contained lead.

A 2020 study conducted by Illinois Wesleyan University found 48% of the ground venison packets collected from shot-harvested deer were found to have metal fragments. Of the seven tested, all had various concentrations of lead.

Given Harper, one of the authors of the study and a hunter himself, said the fragments found were so small that if one were to eat it, they would likely be unaware.

“They were on the size of millimeters,” he said. “I mean the particles much smaller than that would not show up on the radiographs but you know certainly any fragments present in venison, any lead fragments then can be ingested by people and have some really harmful health effects.”

After the 2008 North Dakota study, Iowa paused distribution of donated venison and decided to test 10 two-pound packages for lead.

“We partnered with our health department, we collected some samples, sent it to the laboratory and we had 80% come back as a non-detect and then the other 20% was just a trace,” said Mick Klemesrud, the information specialist with the Iowa Department of Natural Resources.

Of the two packages that tested positive for lead, the levels recorded were .59 parts per million (ppm) and .73 ppm. While there’s no standard for lead levels in meat in the United States, the European Union has a limit of .10 ppm for meat including bovine, sheep, pig and poultry.

A public records request of emails sent between Iowa DNR and the Iowa Department of Public Health (IDPH) in 2008 revealed the health department questioned the decision to pause distribution of donated venison in response to the North Dakota study.

Emails show the health department pushed for the DNR to release a statement making it clear there were no documented cases of lead poisoning tied to consuming venison.

“I’m optimistic that reason will prevail once the general public understands that the exposures studied in (North Dakota) DID NOT CAUSE anyone to be lead poisoned using current definitions,” wrote Ken Sharp, who at the time was director of the division of environmental health with the Iowa Department of Public Health. “I hope this is just a bump in the road and we can put all of this behind us sooner than later.”

When asked if Iowa is planning any future study of the issue, Klemesrud said there are no plans to do so at this time.

According to the CDC, “No safe blood lead level in children has been identified. Even low levels of lead in blood have been shown to negatively affect a child’s intelligence, ability to pay attention, and academic achievement.”

Iowa officials say there are no recorded cases in the state of lead in venison causing lead poisoning in children.

But while DNR websites for a number of states mention potential risk of lead in game meat, the information listed online by state health departments in Iowa, Kansas, Nebraska and Missouri does not include game meat as a potential source of lead. The only possible food mentioned as a source of lead exposure are some international foods.

Testing for lead can be inconsistent between states, with different policies for children based on where they live, if they are on Medicaid, if enrolling for the Women, Infants and Children program, or WIC, and level of risk to lead exposure.

x

“In society today, we are dealing with, and we have been dealing with, low level lead exposure, that doesn’t cause any symptoms,” said Michael Kosnett, a professor with the Colorado School of Public Health who specializes in occupational and environmental medicine and toxicology.

But while lower levels do not cause the same clear symptoms that higher levels would — including stumbling or the inability to maintain a normal level of consciousness — they can still cause harm.

“It causes adverse effects in the developing nervous system of children,” he said. “It could cause a loss of IQ.”

Kosnett published a study in 2008 showing that eating venison and other game meat shot with lead ammunition could raise an individual’s blood lead level, but he notes frequency of consumption must be taken into account.

“If there’s consumption just occasionally, few times a month or not on a regular basis, the risk is going to be much lower than if that is your major and sole source of protein,” he said. “If you have a family that the donated meat is the sole source of protein, and it’s going to be consumed regularly, there’s more of a basis for concern.”

Wisconsin researchers conducted a study that took samples of venison meat and determined the lead levels in the packages. They then took those results and estimated a child’s risk of having an elevated blood lead level consuming venison in different quantities.

The study concluded that, “a completed exposure pathway exists for the ingestion of lead-contaminated meat,” and that there is a “predicted risk of elevated lead levels in blood among children consuming venison shot with lead ammunition.”

The study also noted there have been no confirmed cases of elevated lead levels caused from consuming venison and that there is also a wide variation in the potential amount of lead in a venison meal. It concluded that the issue is an “indeterminate public health hazard.”

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) certifies meat lockers. But neither the USDA nor the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulate lead leaves in donated venison meat because it is not being commercially sold.

While it doesn’t regulate donated venison, the FDA does set lead levels in things like fruit juice. It recently proposed lowering the allowable amount of lead in apple juice from 50 parts per billion (ppb) to 10 ppb and to 20 ppb for other fruit juices.

During deer hunting season, Mike Evinger, owner of meat locker Mikes Meats in Knoxville, Iowa, says he sets aside one day a week to process up to about 500 pounds of venison. About 100 pounds of that goes toward the HUSH program.

Evinger believes he does his best to reduce chances of lead getting through the process by making generous cuts around the wounded areas of the deer and even going so far as to reject any that have too much trauma.

“It seems like every year we will get some caught up in that grinder,” Evinger said of lead fragments. “I mean, we cut our meat up pretty fine. We don’t leave big chunks and it still gets by us.”

Studies, including one in Minnesota, have found lead ammunition can fragment up to 18 inches from the wound and be as tiny as a piece of grain, unable to be seen by the human eye and needing an X-ray to help detect.

In Minnesota, the state X-rays packages of shot-harvest venison meat after it has been processed to discard any visible lead-contaminated meat.

“The last six years, we averaged about 10%,” said Nicole Neeser, division director of the dairy and meat Inspection Division at the Minnesota Department of Agriculture. “That’s still a very significant amount of meat that’s getting thrown away because it has lead particles in it.”

As a state-managed program, Neeser believes donated venison should be held to the same standard as food that consumers would purchase from a grocery store.

“Oftentimes people ask like, ‘well a little exposure doesn’t hurt anyone,’” Neeser said.

But, she said, why should anyone have to take that risk?

“We are working with a product that’s going to what I would say could be a very vulnerable population.” Neeser said, “Folks that are visiting shelves and maybe immunocompromised, young children, pregnant women, nursing mothers, where the effects of lead definitely could be very significant.”

The leaves crunch on the forest floor as Pete Eyheralde takes a few steps and then scratches the ground with his right foot to mimic a hen hunting for food. This is one of the ways he moves through the forest to attract a turkey when hunting.

The Oskaloosa, Iowa, resident made the switch to non-lead ammunition more than a decade ago. While conservation of wildlife is his primary reason for using copper slugs, he also sees making the switch as a way to eliminate health risks to his family.

“You don’t hear about people ending up in the hospital from eating lead from venison or something,” Eyheralde said. “But at the same time, why take a risk if you don’t have to?”

In 2013, a petition was filed with the Iowa DNR asking to require that shot-harvested deer donated to the HUSH program be killed with non-lead ammunition. The petition was eventually rejected, with the state saying Iowa’s department of health “has found no evidence linking human consumption of venison to lead poisoning.”

Eyheralde suggests finding more ways to educate hunters on the risks of using lead-ammunition. He thinks donation programs could be encouraging hunters to try lead-free options.

“Maybe,” he said, “when they donate it say, ‘Hey, here’s a box of copper slugs.’”

Unleaded is a joint investigation by The Missouri Independent and the Midwest Newsroom exploring the issue of high levels of lead in children in Iowa, Kansas, Missouri and Nebraska.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Samantha Horton is a Fellow in NPR’s Midwest Newsroom and the Missouri Independent, based in Indianapolis, Indiana.

MADDIE SOFIA: This is Science Friday. I’m Maddie Sofia. And now it’s time to check in on the State of Science.

SPEAKER 1: This is KERA News.

SPEAKER 2: For WWNO.

SPEAKER 3: St. Louis Public Radio News.

SPEAKER 4: Iowa Public Radio News.

MADDIE SOFIA: Local science stories of national significance. In some Midwest states, venison is an important source of protein available in food banks. That meat is often donated by hunters. But some hunted venison can contain lead fragments. AND Kansas, Missouri, and Nebraska don’t require warning labels about that at food pantries. Food safety advocates say that’s a big problem because some people who use food banks are already at increased risk for health complications.

Joining me today to walk us through this story is my guest, Samantha Horton, fellow with NPR’S Midwest Newsroom and the Missouri Independent, based in Indianapolis, Indiana. Welcome to Science Friday, Samantha.

SAMANTHA HORTON: Thanks for having me Maddie.

MADDIE SOFIA: OK, let’s talk about how the venison actually gets to the food bank in the first place. I mean, how does the meat go from hunters to shelves?

SAMANTHA HORTON: Yeah, absolutely. So a lot of states have hunter harvested donation programs, where hunters go and hunt, and then they choose to donate what they kill to food banks. So, for this story, when we we’re talking about deer season, a hunter kills a deer, takes it to a meat locker, and the program has meat lockers listed that participate in the program.

And so those lockers then will process the deer by cutting it up, grinding it, and then packaging all the meat up into packages that the program has designated as the official packaging. Then those get shipped off to food banks. And then those food banks decide how to distribute it among their local population.

MADDIE SOFIA: OK, got it. Samantha, do we know how common it is to find lead in donated venison?

SAMANTHA HORTON: So that’s probably the hardest thing to put a number on. And it’s just because not necessarily a lot of states have in-depth studies or research that they’ve done, looking at this. One state that I talked to, Minnesota, who does examine their donated venison, they say that they have, in the past six years or so, discarded about 10% of the packaging that they have found to have lead in it. So it’s still a decent amount that they feel.

Iowa did test 10 packages and found two of them to have traces of lead in them. But talking with experts, there’s a concern there because some pointed that that’s not necessarily a large enough sampling to really get an idea of how common of an issue that would be for the state.

MADDIE SOFIA: And are people finding lead levels in donated venison high enough to be dangerous? And who’s most at risk?

SAMANTHA HORTON: Yeah, so these are low levels of blood that we’re talking about. So a lot of the things I talked about with people was the frequency that someone would consume game meat that plays into this possibly. But at the same time, the CDC has stated that there is no safe blood lead level in children that’s been identified.

So there starts playing this whole part of, is this preventable? Is this maybe another source of exposure for folks? That’s a part that becomes a concern. And it’s one more exposure. While it might not be high enough to have a blood level that would cause them to investigate it, it still could cause harm. And for children, that can include effects to IQ and behavior.

MADDIE SOFIA: Got it. I mean, what kind of warning labels for lead exist in the Midwest states that you looked at? Are people aware of this?

SAMANTHA HORTON: So the only state I found a label for was Iowa. And that’s actually how I started this whole story, was with Iowa’s labeling, because it was interesting. It was something I didn’t see other states having at all. And I mean, their label reads, lead fragments may be found in processed venison. And I note that children under six years and pregnant women are at the greatest risk from lead.

But at the same time, they put in bold that Iowa has not found cases of lead poisoning from lead in venison. And so it’s there, but it’s also where there’s a lot of, I feel like questions that become a thing then of, why did this have to be put on the packaging? Is it enough of a concern to have a warning? Should more be done to prevent it? Why is there maybe not more research the state could be doing possibly to understand that?

MADDIE SOFIA: I mean, how do states actually test for lead in venison?

SAMANTHA HORTON: So Minnesota is one of the only state that I came across that actually has a testing program for their donated venison, which really stood out to me. They X-ray all their shot harvested venison. It costs about $7,000 to $10,000 each year, transporting the meat to a testing facility. They’ll X-ray it. And I spoke with Minnesota Department of Agriculture’s Nicole Neeser about if she thinks it’s worth the money to test. And she said it is.

NICOLE NEESER: Well, we look at it as a public health safety issue. It definitely is one that we have to address. And we would ask other processors to do the same. I don’t think anyone would be excited about food in their refrigerator if they knew that it had lead in it.

SAMANTHA HORTON: This becomes a food justice issue and the question of why people shopping at food pantries should expect anything less than what people who shop at commercial stores would expect.

MADDIE SOFIA: Keeping that all in mind, do you think we could see changes in how states test for lead in the coming years?

NICOLE NEESER: So talking with a lot of people during this reporting, that’s something that I heard a lot, is just this hope that from this reporting or just from this conversation happening, that states will consider at least testing their donated venison this next upcoming season in the fall and winter, just to get a better idea how much of an issue it is in their state, just becoming aware of it, because I think we just need more information. There’s just, I think, a gap in the knowledge. And people want to know more.

MADDIE SOFIA: OK, that’s about all the time we have for now. I’d like to thank my guest, Samantha Horton, fellow with NPR’s Midwest Newsroom and the Missouri Independent, based in Indianapolis, Indiana. Thanks for joining us.

SAMANTHA HORTON: Thanks for having me.

MADDIE SOFIA: You can read her full story on our website, sciencefriday.com/stateofscience.

Copyright © 2022 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Kathleen Davis is a producer and fill-in host at Science Friday, which means she spends her weeks researching, writing, editing, and sometimes talking into a microphone. She’s always eager to talk about freshwater lakes and Coney Island diners.

Maddie Sofia is a scientist and journalist. They previously hosted NPR’s daily science podcast Short Wave and the video series Maddie About Science.