Do Weather Instruments Need a Robot Repairman?

17:19 minutes

Well before anyone suspected that a freak mid-March blizzard could be headed their way, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association was predicting a storm might be brewing. One of its weather satellites, situated 22,300 miles above the Atlantic Ocean, was keeping track of two low-pressure systems as they headed for a collision, creating a super low pressure system that would then go on to drop as much as two feet of snow in parts of the northeast. That satellite, called GOES-East, is part of a network of geostationary weather satellites that help scientists keep track of weather systems affecting the United States.

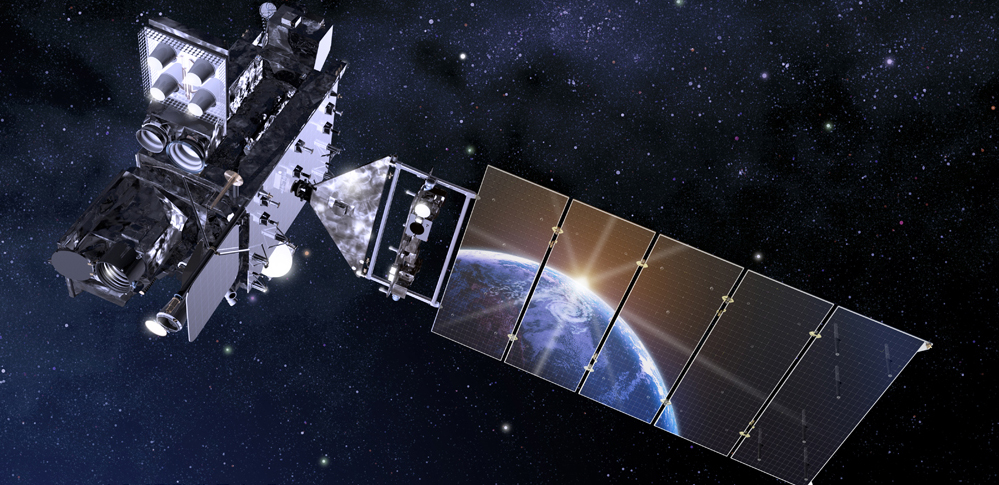

Last November, NOAA and NASA jointly launched the GOES-16, the first in a new generation of weather satellites with more advanced capabilities. The imaging device on GOES-16 has four times the resolution of older models, and can provide images of weather patterns and severe storms every 30 seconds. Also onboard the GOES-16 is a brand-new tool, a geostationary lightning mapper, which will help forecasters and firefighters identify areas prone to wildfires sparked by lightning. The new mapper also detects in-cloud lightning, which often occurs five to 10 minutes before potentially deadly cloud-to-ground strikes, according to the NOAA website.

But the important information we receive from these satellites does come at a price. Once launched into geostationary orbit, there is no way to inspect or service them if something goes wrong at any point during their lifespan. Software fixes may be possible, but hardware can’t be replaced. That’s why DARPA is looking to develop a technology that’s never been tried before—a robot repairman that could fix satellites in geostationary orbit.

It’s still early days, but Steve Oldham, the senior vice president of Space System Loral (SSL), the leading commercial satellite provider, is excited to help DARPA solve the problem of repairing satellites in space. His grand vision for satellite-servicing in space involves a robot that could be sent to geosynchronous orbit and serve multiple satellites located near each other, just like a AAA serviceman out on the road.

[Meet the space archeologist who uses satellites to discover ancient historical sites.]

The spacecraft wouldn’t be able to do extensive repair work on current satellites, mostly because those weren’t built to be taken apart and put back together. But SSL and other private companies working on this problem imagine a service spacecraft that could possibly extend the life of an older satellite by shuttling it to another location in geosynchronous orbit or even refueling it. Such a device could also use its robotic arms to “unstick” a solar panel or antenna that didn’t deploy properly.

Oldham joins Ira along with Michael Stringer, the assistant system program manager for NOAA’s GOES-R satellites, to discuss the future of satellite servicing and weather forecasting.

*This copy was updated on March 17, 2017 to indicate that the GOES-16 satellite was launched last November, not last December, as originally stated.

Steve Oldham is Senior Vice President for Strategic Business Development at SSL (Space Systems Loral), based in Palo Alto, California.

Michael Stringer is the Assistant System Program Director for GOES-R satellites at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA) in Washington, DC.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. As you know, mother nature delivered a mid-march blizzard to those of us in the Northeast this week and those of us trying to get back to the Northeast this week, dumping up to two feet of snow in some places. But while it might have been unusual for this time of the year the storm was not actually surprising. One week earlier, weather satellites run by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration– you know it as NOAA– began tracking two low pressure systems whose paths were on a collision course.

So when these two systems came together to create one giant low pressure snow monster most people were ready. And whether we know it or not we rely on information from satellites in low Earth and geostationary orbit every day. We have weather cell phone stuff like that. So what if something up there breaks? We can’t in most cases just send up a repair person to make a house call. He can’t do anything about it except use another satellite or send up a new one and that costs hundreds of millions of dollars.

Which is why scientists are looking into whether it’s time we built something that could fix a satellite like a robotic repairman. Joining me to talk about these important weather instruments and what it would take to give them their own AAA mechanic so to speak, are my next guests. Steve Oldham is a senior vice president for strategic business development at SSL which builds satellites at Space Systems Loral and Michael Stringer assistant system program director for the GOES-R satellites at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association. And NOAA welcome to Science Friday.

STEVE OLDHAM: Thank you

MICHAEL STRINGER: Thank you very much.

IRA FLATOW: You’re welcome. Michael, so what weather satellites are we working with right now?

MICHAEL STRINGER: So NOAA has and operates polar satellites that go from pole to pole circling the planet approximately 14 times a day. And the Earth is rotating underneath so we see the entire planet. And those satellites allow for our global forecasting to predict the weather out into a week or more in advance. Then we have the geostationary satellites– which is the program I’m on– that stays over the same point of the Earth. And so the satellite’s out at 22,300 miles and it orbits at a speed that stays over the same point. So we can constantly be looking at the Western hemisphere.

IRA FLATOW: So its orbit is going at the same rate that the Earth turns so it appears to be staying in same spot but it’s synchronized. And how long have the satellites been up there?

MICHAEL STRINGER: We’ve been operating satellites up there for over 40 years. And especially at the geostationary ones. And so that GOES-R series is the fifth generation of GOES satellites.

IRA FLATOW: And last November NOAA sent up GOES-16 with all kinds of new features sort of like a new version of the iPhone? What can the GOES-16 do better than our current satellites?

MICHAEL STRINGER: So the GOES-16 is a total weather satellite looking at the sun and its weather, looking at space weather right around the spacecraft, and most importantly looking at the Earth weather with two main sensors. One is our advanced baseline imager which is three times more spectrum or different color bands than the current satellites. It has four times the resolution of the current satellites. And it’s five times faster. Then the other instrument is a geostationary lightning mapper. So we can now watch the lightning from geostationary.

IRA FLATOW: Now there are things that do stop working on the satellites right? I mean right now we have satellites that have parts that are not working but they have spare parts that back them up.

MICHAEL STRINGER: Correct. We build our satellites with redundancies in the different parts so that if one part fails, we still have backup parts. And we also right now have– on the operational side– the legacy satellites. We have three that are ready for operations. We have an east satellite, a west satellite, and a satellite that’s in a on orbit storage position. So that in case there would be an issue with one of the operating east or west satellites, we could move the storied satellite into position rather quickly.

IRA FLATOW: Now Steve Oldham it seems quite relevant and quite clear here that we really need these satellites and we need to have them working all the time. Why haven’t we looked into repairing satellites in orbit before? Why now?

STEVE OLDHAM: That’s a great question. We tend to forget that space is the invisible infrastructure that we’re all critically dependent on. It’s not just weather, it’s communications. We have an expectation of a cell phone signal wherever we go of connectivity anywhere on the planet, of excellent weather forecasting like NOAA provide. But space is providing that. And space works on a throw away culture.

So right now we build a satellite. It goes a long way up in the air. It lasts a long period of time. We design them as well as we can. As Michael was mentioning, they’re designed to be redundant and have the ability to failsafe. But problems occur. They occur all the time. Satellites can go into the wrong orbit. They can have antenna failures, deployment failures. And we don’t service them. And think of any other element of our infrastructure. Our traffic systems, our water systems, sewage, power. The idea of not servicing on a regular basis these things really makes no sense.

So the reason we don’t is because the technology today hasn’t existed. And that’s what we’re now working on.

IRA FLATOW: You’re working with DARPA and building a satellite that could go up and repair other satellites?

STEVE OLDHAM: Yeah there are a couple of programs that have been instigated over the last few months. NASA is developing a program that will refuel– put more fuel into low Earth orbiting satellites called Restore. And DARPA is producing an advanced system that will allow not just repair and life extension, but also assembly and augmentation of satellites in space. And SSL which is– for those people who don’t know SSL, we’re in Palo Alto, California– and we export more satellites worldwide than any other American company. And we are the partners of both NASA and DARPA on those two programs.

IRA FLATOW: Now there’s a free plug for you guys. I guess being a handy guy myself– I repair little things around the house– I know that to repair something it has to be made so you can repair it right? So you can take it apart easily and replace the part that’s going bad. Are the satellites– the weather satellites that are up there now– are they built so that they can be repaired? I mean if you’re going to send up a repair truck or whatever, a robot, you have to be able to get the parts out and put the new ones in don’t you?

STEVE OLDHAM: So it’s a 2-step process. The satellites that are up today in both Geo and Leo. We can rendezvous with them– by which I mean we can fly up to them and connect with them. And we can do certain operations. We can extend life. We can do literally the same as you do with your car when you fill it up at the gas station. Unscrew the fuel cap and pour more gas in. We can do certain amounts of repair. If an antenna is stuck. If it didn’t deploy properly, for example, we can fix that.

In the future I expect to see satellites that are built like our laptops. Where you have the equivalent of a USB port and you assemble the satellite using the USB port. You plug parts in. Later on if a part fails, you pull that one out, you plug another one in.

IRA FLATOW: And that’s kind of what you need. What would it take, Michael, to build a satellite that could be taken apart easily and put back together in orbit?

MICHAEL STRINGER: Well what we would like to see is demonstrations like Steve’s looking at where we would see how those would work. And then we would investigate that in the future to see how we would build those new satellites.

IRA FLATOW: And so it’s sort of a chicken or egg thing here? You go up now and see if you can repair them or parts of them and see what you have to do in the future to make it easier?

MICHAEL STRINGER: Right. Satellites would have to be made, like Steve said, more modular to be able to do it. GOES-R– the new series– does not have that modularity. So there’s only limited things they could do.

IRA FLATOW: Well looking at the new budget that the president has put out for various science projects and the weather and having people in Congress. I remember famously when Jane lubchenco– when she was head of NOAA– was asked by a Congressman why we need weather satellites when you can get all your weather from the Weather Channel. I mean does Congress have any idea about how the weather satellites work? No one wants to touch that one.

MICHAEL STRINGER: I’m going to just say we are constantly briefing Congress about our satellites and about our progress and giving them the updated information about how well GOES-16 is doing and how much more details it can see and how we were monitoring this storm this last week and what was happening with that. And all the advances in that that we’re going to be able to get out of this new technology.

IRA FLATOW: But I’ve got a serious question. When you’re looking at new budget figures, is NOAA a high priority? Especially to build their weather satellite

MICHAEL STRINGER: Well I’m not the one to talk about the budget process. I’m not really in that part of it. We can get you the names of folks that are the appropriate people to talk about the budget.

IRA FLATOW: I’m sorry I shouldn’t have asked you to answer a question outside of your pay grade which is how they say it in Washington. Let me go back to the science and technology here. How much would it cost then to build a satellite repair robot? Is this something that we have to worry about breaking down in orbit too, Steve?

STEVE OLDHAM: So what DARPA are doing on that program is they’re doing basically a public private partnership. And the reason they’re doing that, the government puts up half the costs and SSL is putting up about half the costs. And it’s a multi-hundred million dollar activity. Once the satellite is up in orbit though it can then move around the Geo belt for the next 15 years doing maintenance operations, life extension operations, inspection, repair, augmentation. And the reason DARPA are doing it that way is because they want the buy-in of the industry.

To Michael’s point, nobody’s going to start building satellites to be modular and assembled in orbit until you know that the capability exists up in space to be able to deal with it. So the best way to ensure that is to choose a commercial partner and have the commercial industry and the government industry both receiving this demonstration and starting to implement it. So we’re already at SSL building satellites that are modular. We have designs for those. We’re working with our commercial customers on those. It’s an exciting capability and we’re looking forward to demonstrating the ability to do this plug and play through the DARPA mission.

IRA FLATOW: 844-724-8255 Is our number talking with Michael Stringer who is system program director at the GOES-R satellite at NOAA. Steve Oldham’s senior vice president for strategic business development for SSL. If you were going to build a new satellite Steve, what more tricks– I mean it takes years, right, to get these things on the drawing boards? Probably the satellite– the new GOES– has probably got stuff that’s years old on it. What kind of new things would you want to put into it that you don’t have already?

STEVE OLDHAM: So what we would like to see in the architecture going forward is the idea that instead of building a satellite you first build a platform. And the platform is built like a shopping mall concept. So you put up your shopping mall– your platform. And then you add to it the capabilities that you want according to market need. So for example in the case of Michael’s weather satellites, I’m sure NOAA would envisage a certain set of instruments that they want on board initially. And you put those on.

Then three, four, five years later there’s a need for more accurate weather assessment. Those better instruments have been developed. And instead of having to wait a long time for the next satellite, instead you launch just that payload. Just the instrument. And you plug it into the outside of your existing platform. And now instead of going through the cycle of a large capital expenditure to build a satellite followed by a lengthy period of operations, now NOAA and other users can constantly itterate and get the newest technology available much faster.

IRA FLATOW: So you basically want to build a rack mounted satellite.

STEVE OLDHAM: Yeah it’s a combination of that concept. And you said it very well, the AAA. Yeah we would like to be the AAA of space. It’s a great business model and a great capability.

IRA FLATOW: Can’t top that line so I’ll give out the ID. I’m Ira Flatow. This is Science Friday from PRI– Public Radio International. And you’d be making house calls if you were the AAA. How many satellites– there are tens of thousands of satellites out there now would you say?

STEVE OLDHAM: In geo there is a smaller number than that. It’s probably in the 1,000. In Leo there’s many more. I’m sure you’ll have done segments and heard about the small micro and cube satellites that companies like Planet are doing now. So there’s many, many more satellites in Leo. In geo it’s a lot further away. You need larger satellites and there’s less of them.

IRA FLATOW: Michael how much money do we spend on the weather satellite program now?

MICHAEL STRINGER: So the GOES-R satellite program which is from the early 2000s in the concept development and the instruments and planning all that out. Through building four satellites– we’re building four– so GOES-16 was just our first one. We’re going to be launching GOES-17 just a little under a year from now. And then we have two more after that. And then we’ll operate those out to 2036 and that total cost was $10.8 billion dollars.

IRA FLATOW: Now that’s got to be a lot less than what you would pay for for a storm– whether it’s a natural disaster like a hurricane or the snowstorms that we just had or something like that– by having this satellite. Even though it sounds like a lot of money, you’re saving money in the long run.

MICHAEL STRINGER: Right. So every year there are multiple billion dollar events that happen that are weather related. And so by NOAA having this valuable infrastructure to get the word out to the public that these events are about to happen they can take shelter, they can move products into safe locations. And FEMA can stand up and be ready to support those rescue operations by pre deploying to a safe area just before the storm. And as soon as the storm clears they can be ready to move in.

IRA FLATOW: Let me go to a quick question from Richard in Jacksonville, Florida. Hi there, welcome.

RICHARD: Hi Ira. Glad to be on. My question was regarding the comment earlier about the commercial satellites. When I turn on the local Weather Channel or I turn on my local Comcast station. Is the imagery that I’m seeing is that NOAA imagery or is that coming from a commercial product? Thank you.

IRA FLATOW: You’re welcome.

MICHAEL STRINGER: That’s NOAA imagery often enhanced by the commercial vendors. They take our NOAA data and then when we have 16 different channels– which is different color channels and IR– they can take that information and blend it together in different ways to give enhancements to that before it comes out onto the TV broadcast.

IRA FLATOW: How do you work with the NASA weather satellites? Are you integrated with them at all?

MICHAEL STRINGER: So we’re actually in partnership. The GOES-R program is a joint NOAA-NASA program. And so we work very closely with NASA on building these satellites.

IRA FLATOW: And then also the information that comes out is available to both of you?

MICHAEL STRINGER: Yes, yes.

IRA FLATOW: Quite fascinating. I think we’ve got a primer on everything you wanted to know about the weather satellites. I want to thank both of you for taking time to be with us today. Steve Oldham, senior vice president for strategic business development at SSL which builds all those satellites. Michael Stringer, assistant system program director for GOES-R satellites at NOAA. Thank you for taking time to be with us today.

MICHAEL STRINGER: You’re very welcome, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: Thank you. Coming up, what’s the best story you have ever heard? Whatever it is, my next guest thinks he has a better one. We’re going to talk about the quest to understand the universe. And a physicist’s answer to why are we here? Lawrence Krauss. Physicist Lawrence Krauss joins us. We’re going to talk about physics and talk about a little bit of budgets for science. Stay with us. We’ll be right back after this break.

Copyright © 2017 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of ScienceFriday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Katie Feather is a former SciFri producer and the proud mother of two cats, Charleigh and Sadie.