A Scientist’s Catalog Of 100 Days Under The Sea

22:14 minutes

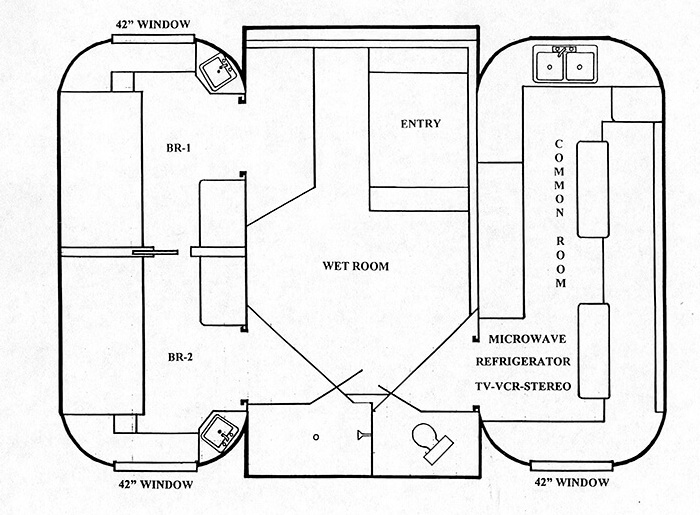

In February, Dr. Joe Dituri put on his scuba gear, dove 30 feet below the surface, and entered a 100-square-foot underwater lodge. This former US Navy diving officer didn’t come up again for air until June 9, spending 100 days underwater. And even before the end of his stay, he broke the record for living underwater.

He did all of this in the name of science—to understand how the human body handles long-term exposure to pressure. This mission is called Project Neptune 100, and because those 100 days are finally up, we’re taking a deep dive into the underwater habitat to hear what is to be learned from so many days below the waves. We recorded this interview with Dituri on Day #94 with a live virtual audience, whom you’ll hear from later.

Ira talks with Dr. Deep Sea, aka Dr. Joe Dituri, a biomedical engineer and associate professor at the University of South Florida, and Dr. Sarah Spelsberg, wilderness emergency specialist and the medical lead for Project Neptune 100 coming to us from the Maldives. Check out some photos of Dr. Dituri’s undersea life.

Joe Dituri is a biomedical engineer and associate professor at the University of South Florida.

Sarah Spelsberg is a wilderness emergency specialist and the medical lead for Project Neptune 100.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow.

100 days ago, Dr. Joe Dituri put on his scuba gear, dove 30 feet below the surface, and entered a 100-square-foot underwater lodge. This former US Navy diving officer hasn’t come up for air until today, day number 100. And during his stay, he broke the record for living underwater weeks ago.

But what’s the point? Well, he did all of this in the name of science, to understand how the human body handles long-term exposure to pressure. This mission is called Project Neptune 100. And because those 100 days are finally up, we’re taking a deep dive– well, maybe not that deep– into the underwater habitat to hear what is to be learned from so many days below the waves.

We recorded this interview on day number 94, with a live virtual audience, whom you’ll hear from later.

So joining me now is Dr. Deep Sea– Dr. Joe Dituri, a biomedical engineer and associate professor at the University of South Florida, joining us from the bottom of a lagoon in Key Largo, Florida. Also, Dr. Sarah Spelsberg, wilderness emergency specialist and medical lead for Project Neptune 100, coming to us from the Maldives.

Welcome to Science Friday.

SARAH SPELSBURG: Thank you. Thank you very much for having me.

JOE DITURI: Hey, thank you for having us. We appreciate it.

IRA FLATOW: Nice to have you. You’ve been living there underwater for more than 90 days. Is there an action or something about your body that has surprised you the most about living underwater for so long?

JOE DITURI: Interestingly enough, two things– the compelling shortness. I was 73 inches when I started this thing, and I used to scrape my head right on the emergency escape hatch. I no longer scrape my head. I believe I’m shrinking. Although the doctor will tell us the details when I come to the surface on that measurement.

Secondly, for instance, last night, I slept about 7 and 1/2 hours. Five of those hours– five of those hours– were in deep or REM sleep. Unheard of sleep cycles down here like you would not believe.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. Do we know why that is?

SARAH SPELSBURG: I go into these research projects without– try to go in without preconceived notions and try not to spend too much time obsessing about the data early on, until we have enough to do the statistics. And I think the noise and I think the depth and I think the pressure and gentle vibration down there, I think they all play a role in creating this sleep bubble.

IRA FLATOW: Hmm. And Joe, tell us what you’re trying to accomplish with this 100-day mission.

JOE DITURI: So it’s a threefold purpose actually. And the first part is I have a PhD in biomedical engineering, therefore, I want to do biomedical research on the human. You leave it in an isolated, confined, extreme environment for 100 days, what happens? 19 psychological and psychosocial tests before, all the way through and during, and then afterwards. 200 blood, urine, and saliva tests. We basically do electrocardiograms on the heart on a regular basis, electroencephalograms for the brain, to see what happens with the coherence, what happens to the phase lag while it’s down here, the alpha-theta ratios. We’re checking all that stuff, and we’re just pointing it in this direction.

We’re also doing pulmonary function tests to see if there’s a decrease in vital capacity or whatever happens after you leave somebody in this high, partial-pressure-of-oxygen environment. And that’s only the first thing that we do.

And the second thing is we get to do outreach to kids. And to date, we’ve gotten almost 4,000 kids that we have physically talked to– that I have physically talked to in some way, shape, or form– in less than 100 days. So the numbers are staggering, and we’re out there doing good stuff.

We’re talking to them about science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. And these kids are so much better at technology, and they’re born scientists. So I’m just reiterating to them that they can do stuff that’s fun in a fun place, like the ocean, where I am.

IRA FLATOW: Right.

JOE DITURI: And then, third and finally, I’m talking to the greatest scientists on the planet about preserving, protecting, and now rejuvenating the marine environment. PhDs and marine science and shark research and sponge research, anything that’s going on– ichtheology. And we’re just trying to figure out how we can do this better.

For instance, we learned how to transplant and replant coral on a coral reef.

IRA FLATOW: Really?

JOE DITURI: Oh, absolutely. I was just talking with a whole group of kids two days ago. It was great.

IRA FLATOW: That’s terrific. So Sarah, tell me– you’re an explorer and a doctor, and sometimes both at the same time– why did you get involved in this project? And what do you view as your mission?

SARAH SPELSBURG: My mission is to make Joe’s vision a reality and to protect the data and make sure we get all of the data that we’re trying to get here. When he told me about this project, I was really enthralled and just thrilled at the opportunity to be a part of it, much less the lead MD for this study.

And I’m interested, too. Because I’ve always been interested in hyperbaric. And I feel like it’s somewhat of an underutilized technology when it comes to diseases. It has applications for wound healing and obviously decompression sickness.

And now, with Joe’s research on traumatic brain injury, it’s showing a lot of promise there as well. And I think there’s promise here for inflammatory conditions and other pathologies for people who are at high risk for cardiovascular disease from what we’re seeing from the data so far.

So I knew getting on board that this was going to be a big deal and exciting. And I don’t think I knew quite how big and quite how exciting it was going to become.

IRA FLATOW: Sarah, you visit Joe to get samples.

SARAH SPELSBURG: I do.

IRA FLATOW: What’s that like?

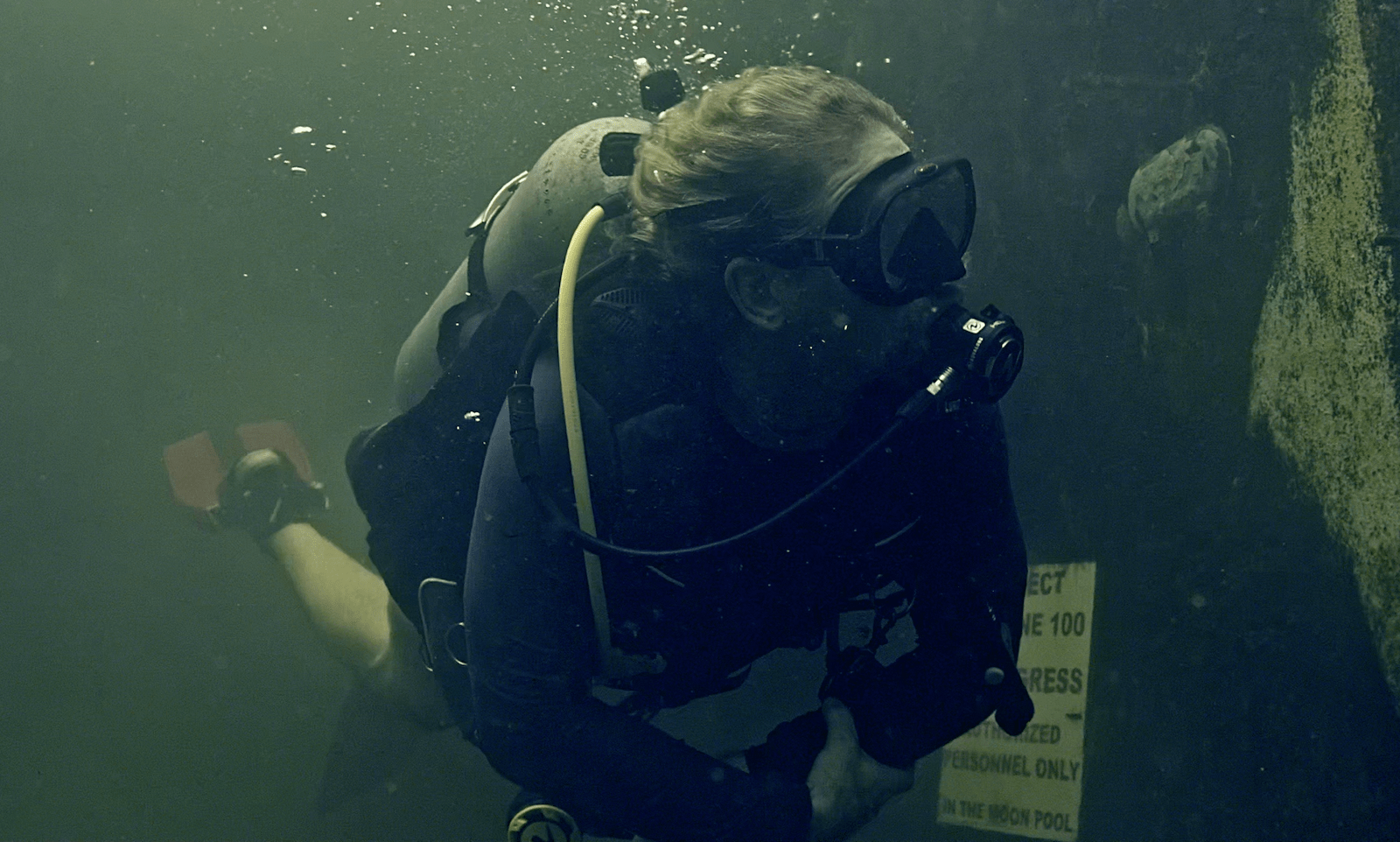

SARAH SPELSBURG: It’s a unique house call. I don’t know that I’ve ever heard of another physician scuba diving down to their patients. And it’s fun and exciting for me. And as we’ve spoken– I’m in the Maldives– I love diving. I love swimming. I love snorkeling. I love marine life. And cleaning up the oceans is a particular passion of mine.

So yeah, I dive down there. I surface in the moon pool. I get myself cleaned up so I don’t drip all over everything. He’s already collected the blood and the saliva specimens. But then I draw his blood underwater. And we’ve ultrasounded him underwater to take a look at his heart and lungs. And we’ve done all of these interesting house calls underwater.

IRA FLATOW: Is there any difference between collecting blood– drawing blood– on land versus underwater?

SARAH SPELSBURG: Yes. I wasn’t sure what to expect the first time. Because you know how a potato chip bag, if you go up in a plane, it becomes really big. Well, when you go down at depth, it gets really small. And so when I draw his blood at depth, and then I dive to the surface with it, I was deeply concerned that it was going to explode. And so what I did was I drew twice as many vials, but only half full.

And the thing that I think surprised me the most was how fast it came out. He has a normal blood pressure and a very normal heart rate. And the blood just shot out. Like, when I first stuck it in and tried to connect the vacuum tube, it almost shot me off– the power and the pressure.

IRA FLATOW: Wow.

SARAH SPELSBURG: And it was just like, oh, OK, that’s happening. And while we’re filming it, of course. But we got it back on and got the rest of our samples. And it just comes out really fast. Really fast.

IRA FLATOW: Joe, is that because you’re pressurized? How pressurized are you down there, as opposed to being on the surface?

JOE DITURI: We’re at 25 pounds per square inch. The surface is 14.69. And the vacuum tube is zero. So it’s a much greater pressure. So it makes sense. And we knew this, and we had talked it through. We even did a trial run in the moon pool of a syringe full of water just to see what happened. And I was a little daunted at that point. Let’s just put it that way.

IRA FLATOW: Got it. I got it. Sarah, you told us about bringing those samples back to the surface. Do you have any results from the blood samples?

SARAH SPELSBURG: We do. We do have some results. And we have a lot. As he said, we’ve done hundreds of tests. So probably the most compelling to me are that a lot of his inflammatory markers have dropped and stayed down. So it’ll be very interesting to me, then, what happens after he’s been back at the surface for a period of time and we redraw.

Because if they stay down or if they come back up, it opens up the door for hyperbaric to be a treatment option for a lot of autoimmune and inflammatory conditions, like ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s, rheumatoid arthritis.

And then the other thing is his cortisol has gone down. His total pooled cortisol, which is a stress hormone. It’s the fight or flight hormone. When you’re in a chronic state of stress, you might have chronically elevated cortisol. And it can have a lot of effects on the body. And having it go down, it’s very exciting.

IRA FLATOW: So your immune system is tweaked up and you’re relaxing more.

SARAH SPELSBURG: And you’re relaxing more, yeah. And your testosterone is up. Your total testosterone has just gone up.

IRA FLATOW: So you can rip a phone book while being very relaxed.

[LAUGHTER]

SARAH SPELSBURG: It sounds like the life, right?

IRA FLATOW: Well, do you notice– can you feel any difference, Joe, from these things happening?

JOE DITURI: I feel amazing because I’m getting much better sleep. Being in 60% to 66% REM sleep is unheard of for Joe Dituri. I mean, that wasn’t the way that I slept. I was in the military for 28 years. I was always constantly on guard. I had a traumatic brain injury. Therefore, I didn’t generally sleep very well.

So when I was able to sleep and catch up on sleep, now I’m like, wait a minute, wait a minute, wait a minute. I am so much more productive. I’m literally buzzing while I’m down here. And I do all kinds of interviews. And I’m engaged probably 16 to 18 hours a day.

IRA FLATOW: Wow, that’s amazing.

JOE DITURI: I still feel amazing.

IRA FLATOW: That’s amazing. Let me go to our questions from our audience. Nicun has a question about monitoring your heart. Nicun, go ahead.

AUDIENCE: Yeah, I was just wondering if there was any effect on the heart. You were talking about blood pressure. Were there are echocardiograms done? Have we looked at things like pulmonary hypertension, stuff like that? I’m actually in the Navy myself, and I’m a pulmonary and critical care physician. So this is a very intriguing topic. Thank you.

JOE DITURI: Electrocardiograms are done twice a week. Absolutely, we’re checking it. Now, it is just the six-lead EKG. But we’re doing blood pressure testing, and we see no substantial increase in blood pressure the entire time. Oxygen testing, with the little pulse oximeter. And we’re also doing pulmonary function testing every two weeks on this.

Now, I’m at 36% oxygen being as I’m breathing 21% from the surface at this increased pressure. So Boyle’s law squishes it down and Dalton’s law says that the hole has to equal the sum of its parts. So effectively, I’m breathing 36% oxygen at this depth, and the possibility of pulmonary oxygen toxicity is very real.

So especially in the last couple of weeks, we have been reducing the amount of time. And we do this regularly and often. Because I want to make sure– we want to see what depth intolerance is, right?

SARAH SPELSBURG: And then we’ve used a butterfly ultrasound to try to get pictures of the heart and the lungs about once a month. But we haven’t done any really invasive pulmonary hypertension testing. He swims every day, so I try to minimize how many holes I poke in him.

IRA FLATOW: Joe, is your diet and exercise plan different underwater– she talked about swimming– than it was up on the surface?

JOE DITURI: So exercise plan is different. Diet is exactly the same. I’m a creature of habit. I was in the military for a lot of years. I just eat three eggs in the morning, a salad with a lot of protein on it in the afternoon. And then at dinner, I just have high protein and something green as a vegetable.

But what we’re doing is we’re testing out these KAATSU bands. And we’re using resistance band technology. And what we’re trying to do is build muscle. Everything distal to this cup, when it’s pumped up, will be engorged with blood. When it’s engorged with blood, you increase mitochondrial plumpness and you’re helping to basically tire the muscle more quickly.

Then, when you let it up and you let the blood back in– so you get to remove that lactic acid buildup and work the whole left side of the Krebs cycle, which is epic for building muscle– and here we are at the bone-crunching depth still keeping the same muscle tone.

And that is all I have done down here. Zero else exercise whatsoever. Just the resistance bands. And we’ve done muscle size testing. And we’ll see how I’m doing. I mean, I lost 8 pounds when I first came down here. And I needed that.

SARAH SPELSBURG: But we’ve done measurements, and the muscle mass has stayed the same.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday, from WNYC Studios.

Let me go to another question. Earl, from Davis, California. Earl has a question about your process while scuba diving. Hi, Earl. Go ahead.

EARL: Yes, hi. As a scuba diver, it sounds like you’re at a depth where you wouldn’t have to worry about the bends, per se, with surfacing, if you did it slow enough. But I wonder, when you go outside the chamber, how close do you get to the surface?

JOE DITURI: I don’t approach anything closer than 10 feet. That cuts my depth in half. And that’s how they said initially– is if you cut your pressure in half, you don’t want to cut your pressure any more than that. So basically I’m just trying to limit and split the difference between it. In saturation diving, we call it excursion.

There’s a lot of math involved in calculating your decompression. And when you do it, you realize, wow, there actually is decompression. So while the Navy tables and other tables say the word “unlimited,” that’s not exactly true.

Can you get bent? Yes. Have people been bent from this depth? Absolutely, it has happened. Treated at the hospital right here and in the Keys. So I know of them because I get the call all the time. So it has happened.

IRA FLATOW: Right. I have to ask you, being isolated down there, has anything gone wrong medically speaking?

[LAUGHTER]

I love that you’re laughing at this question. There’s got to be something.

JOE DITURI: So what had happened was, on day 12, I called Sarah and I said, what can you do for a cracked tooth? And she said, you did what? I said, yeah. Day 12, I cracked a molar.

IRA FLATOW: Oh, that’s the worst.

JOE DITURI: Oh. Oh, it’s been a rough couple of months. But the dentist couldn’t get me in until July anyway.

[LAUGHTER]

They’re all filled up until July. And I’m like, oh, you’re killing me. I’m like, I happen to be underwater.

But it poses unique problems. Normally what would happen if you have a standard duration between the time you can get to the dentist, you pack it and you seal it with a kit from Walmart or someplace off the shelf, right? But you cannot do that underwater. Because if you seal it here, you have barodontalgia. You come up, and that air has to expand. It’s physics. It works. Pow! Your tooth explodes when you come to the surface if you seal it when you’re underwater.

So it’s kind of a unique kind of a suck it up sort of a situation.

IRA FLATOW: You’re a week from resurfacing. What do you miss most about life on land? And don’t say a pizza. Please, just don’t say that.

JOE DITURI: No. No, absolutely not. No, honestly, that’s what I miss the most– the sun. So realistically, when I came underwater– I’m a creature of the sun– I’d wake up in the morning. I’d go to the gym and then I’d go watch the sunrise. When I went home in the evening, I would go watch the sunset. And I didn’t realize how much it affected my psyche.

So while I have normal circadian rhythm and sleep is amazing, you still miss that sun, that awesome orange orb. So the only supplement I’m taking while underwater for this 100 days is 2,000 IUs of vitamin D because my great doctor told me to make sure of that. Because there will be no sun down there.

SARAH SPELSBURG: I insisted on that. That was the only thing. I said, you have to take vitamin D. We’re not going to mess with the soup, other than that. But you have to take vitamin D.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s talk about what you do for fun. Down there all by yourself, right? What do you do for fun down there?

JOE DITURI: So I’m busy for like 14– 12 hours, at least, a day I’m busy. I’m diving and I’m doing my experiments and doing the outreach and so forth. So realistically, when you say fun, I mean, this is fun for me. I’m being very literal when I say this is my job. So my job is fun, and it’s a passion of mine. So I get to do this.

I get to do this research on a regular basis. And I get to excite a kid about science, technology, engineering, and math. And I get to learn from the world’s experts about the marine science and the world of marine science. So short of that, that’s basically it. I get to relax a little bit. I get to look out this window.

My favorite thing to do is look out this window at night and vary the color of the light and just watch the circle of life happen. The plankton comes out. Then the worms. Then the little creatures.

IRA FLATOW: Have any of the critters adopted you while you’ve been down there? They see you looking out at them all the time, and come up.

JOE DITURI: Oh, yeah. My friend, Fred, the lobster, lives right on a shelf. Oh, my God, he’s right there. OK, so he’s right there right now. Probably he’s literally right there, right now. And I saw Fred molt. So lobsters molt.

IRA FLATOW: Wow.

JOE DITURI: So I saw him doing this type of a motion. And I’m like, what’s wrong with Fred? So I just jumped in, got on my scuba gear, swam out there. And when I did, his body was lying motionless. And I’m like, Fred? And then I saw this pink, gelatinous, gooey thing just skulking away. And I was like, Fred! Fred! And then Fred was gone. And I was like, wait, they molt. He molted. Fred molted in front of my eyes. Oh, my goodness!

IRA FLATOW: It’s a great story. That’s a great story. Sarah, you treat people. How can you take what you learned from this mission and apply it to your patients? Some good information here? Are we going to change medicine at all?

SARAH SPELSBURG: I think we might actually. I think we might. From what we’ve learned here, I am very curious to see what happens with our results once we get him back to the surface. And if the improvements– the decreased cortisol– because he had higher cortisol. He was working hard and he was under a fair bit of stress when we tested him at the surface. And so now it’s gone down well into the green zone. And then, in our second draw, it dropped yet again.

And so if we can find a way to utilize some of this technology to decrease people’s stress or somehow decrease the inflammation, I think we could help a lot of people. We could treat a lot of disease.

IRA FLATOW: Joe, how would you answer that question?

JOE DITURI: So I think we need a fundamental shift in the way we do research, in general. And that’s truly what I think is going to come out of this is a fundamental shift. Everybody wants to know– drug companies want to know– what’s the one thing that– the one variable– if I give you this drug and I isolate everything else, then we can prove that the drug is safe. Well, that proves the drug and that’s it.

But if you’re treating people from a holistic perspective, you need to research entirely differently. You need to look at every single thing and see what changes, and then just make some good assumptions. I realize it’s all rooted in science. But goodness, we got to stay off the drug company model and on to a possibility of actually doing a different kind of research for the human body.

SARAH SPELSBURG: I was just going to say that the sleep quality and the time to exercise, I think if we gave that– if I could encourage every patient of mine to prioritize getting quality sleep and prioritize focusing on getting exercise every single day, I think a lot of these markers would improve in them also.

IRA FLATOW: Do you think we could adapt hyperbaric chambers for more things than we normally do now, Sarah?

SARAH SPELSBURG: Yes. I’m hopeful that the answer to that is yes.

IRA FLATOW: All right. Joe, you’ve been down there almost 100 days. Can you top this? What do you want to do next? Because you look like a guy who is still raring to go about something.

JOE DITURI: I do, in fact. I’m doing my zero-G flight. And I’m going to prove these cuffs and these resistance bands in 0 gravity. And then, hey, Elon, if you’re listening, sir, somebody owes me 100 sunrises and sunsets. So with the speed of rotation of the International Space Station, that’s about 6 and 1/2 days on the ISS. So I’ll trade you straight up.

[LAUGHTER]

IRA FLATOW: Well, there you have it. I want to thank both of you for taking time to be with us today. Quite fascinating and quite really informative. Dr. Joe Dituri, biomedical engineer, associate professor, University of South Florida. He was joining us from the bottom of a lagoon in Key Largo, Florida. And Dr. Sarah Spelsberg, wilderness emergency specialist and the medical lead for Project Neptune 100, coming to us from the wonderful Maldives.

Thank you, both. And good luck to you.

JOE DITURI: Thank you for having us. Great time.

SARAH SPELSBURG: Thank you, Ira.

Copyright © 2023 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Rasha Aridi is a producer for Science Friday and the inaugural Outrider/Burroughs Wellcome Fund Fellow. She loves stories about weird critters, science adventures, and the intersection of science and history.

Diana Plasker is the Senior Manager of Experiences at Science Friday, where she creates live events, programs and partnerships to delight and engage audiences in the world of science.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.