Staying Green, From Point A To B

32:20 minutes

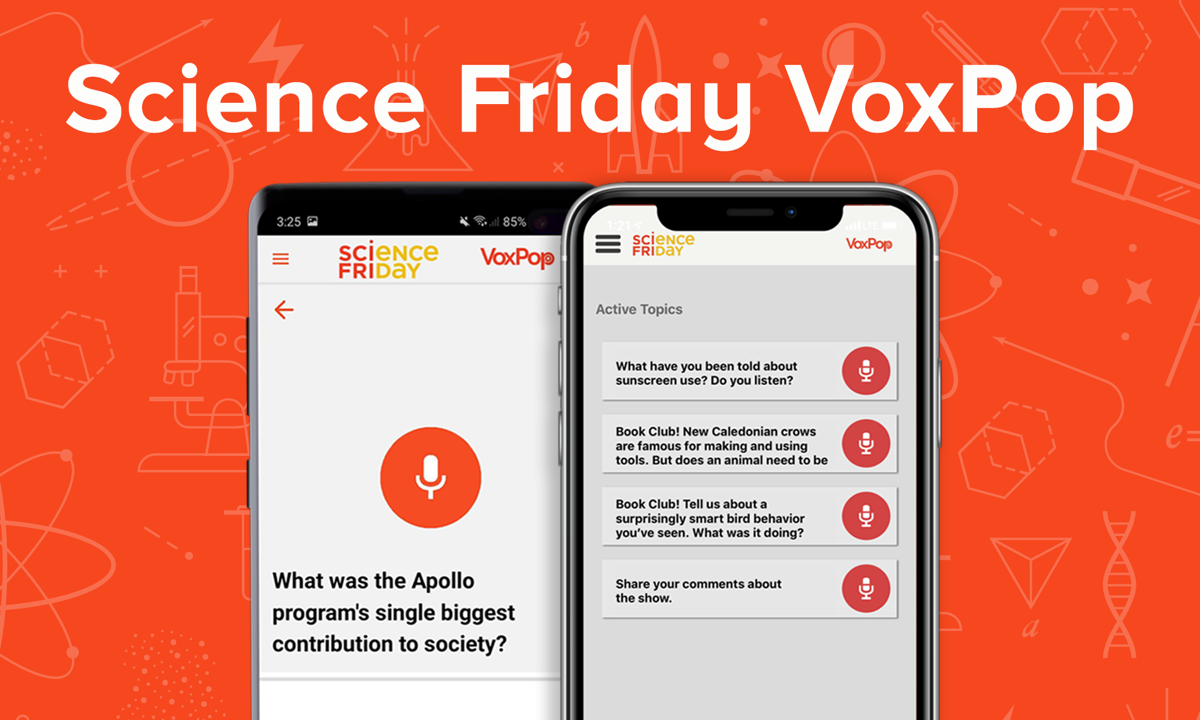

This story is part of Degrees Of Change, a series that explores the problem of climate change and how we as a planet are adapting to it. Tell us how you or your community are responding to climate change here.

Transportation—whether it be your car, aircraft, cargo ships, or the heavy trucks carrying all those holiday packages—makes a big contribution to the world’s CO2 emissions. In the U.S., the transportation sector accounts for some 29% of the country’s emissions, according to Environmental Protection Agency data. And despite the Paris Agreement mission to decrease global emissions, demand for transportation around the world is on the rise—and with that increased demand comes increased energy use. Air travel is growing at a rate of 2-3% a year, for instance—a trend that could cause the emissions effects of air transport to almost double by 2050.

But there are some initiatives and technologies that aim to alleviate the energy costs from this transportation glut.

This week, an all-electric seaplane made a first test flight over the Fraser River in Vancouver, Canada. The craft, a six-passenger DHC-2 de Havilland Beaver driven by a 750-horsepower (560 kW) magniX electric propulsion system, is owned by Harbour Air. The company says it intends to eventually build the world’s first completely electric commercial seaplane fleet. Electrification of the massive planes needed for cargo and transcontinental passenger flights, however, is still a long way off. In the nearer term, researchers are looking to developing biofuels to reduce the carbon impact of flight, along with design and materials changes that will allow for incremental reductions in fuel use.

Also this week, California regulators met to discuss whether to mandate the electrification of cargo trucks within the state. Currently, heavy and medium trucks account for about 23% of the nation’s greenhouse gas emissions. While there are incremental efficiency gains to be made there as well—simple technologies like “skirts” on trailers to improve aerodynamics can have a significant impact—the decarbonization of the cargo fleet is still years in the future.

In this chapter of our Degrees of Change series, we’ll talk about transportation, and some of the technology and policy changes that could be made to make getting around more sustainable. Daniel Sperling, founding director of the Institute of Transportation Studies at the University of California, Davis joins Ira to talk about personal transportation in the U.S., and how individuals get around. We’ll talk with Steven Barrett, director of the Laboratory for Aviation and the Environment at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, about greener flying. And Rachel Muncrief, of the International Council on Clean Transportation, joins the conversation to talk about improving heavy vehicles like buses and cargo trucks.

We asked you about the factors that influence how you decide to travel and use greener transportation. Share your story in the comments below.

Robin in Texas, on the SciFri VoxPop app:

Robin in Texas, on the SciFri VoxPop app:

Hi I’m Robin, and I live in Texas. I often times will travel either to big bend or towards El Paso. El Paso is 500 miles from where I’m at. Currently, there’s not an electric vehicle that can go that far, and it’s like two and a half hours from a hospital at a certain point on the highway. So there’s definitely no electric chargers. We need longer distance.

Get more ideas on how to reduce your transportation carbon footprint, from electric vehicle options to cycling resources.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Daniel Sperling is professor of civil and environmental engineering & the founding director of the Institute for Transportation Studies at the University of California-Davis in Sacramento, California.

Rachel Muncrief is Deputy Director of the International Council on Clean Transportation in Washington, DC.

Steven Barrett is a professor in the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics and Director of the Laboratory for Aviation and the Environment at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Continuing with our Degrees of Change series, this week, climate activist Greta Thunberg was named Time Magazine’s Person of the Year. And you may recall earlier in the year, she journeyed from Europe to the US on a sailboat because the climate impact of air travel was just too great. Transportation, whether it be your car, aircraft, cargo ships, or heavy trucks carrying all those holiday packages, transportation makes a big contribution to the world’s CO2 emissions. In the United States, the transportation sector accounts for some 29% of the country’s emissions, according to EPA data.

So what can be done to reduce the climate impact of all those planes, trains, and automobiles? That’s what we’re going to be talking about this hour. And if you’ve had to rethink your travel options, take emissions into consideration, give us a call. Our number, 844-724-8255, 844-SCI-TALK. You can also tweet us at @scifri. Let me kick off the conversation with my first guest, Daniel Sperling, professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of California, Davis, and founding director of the Institute for Transportation Studies. Welcome back to Science Friday. Dan Sperling, welcome.

DANIEL SPERLING: Well, thank you, Ira. It’s a pleasure to be back.

IRA FLATOW: Nice to have–

DANIEL SPERLING: Yeah, thank you. It’s a pleasure being back.

IRA FLATOW: It’s great to have you. Let’s give a quick breakdown of what we mean when we say transportation. What are the big contributors in transportation to our greenhouse gas emissions?

DANIEL SPERLING: Well, the biggest one is our cars, our vehicles that we personally drive around. The second biggest would be the trucks. And the planes are the third largest.

IRA FLATOW: Trucks, plane, yeah.

DANIEL SPERLING: So if we did a calc– yeah. It’s, yeah, cars, trucks, planes.

IRA FLATOW: So let’s talk about the trucking. Everybody is sending out the gifts for this holiday season. What contribution are all that cargo and trucking making?

DANIEL SPERLING: Well, the trucks overall, there’s a lot of different trucks. There’s the big long haul trucks that are doing the long distance. There’s the smaller delivery trucks. But altogether, if you look at it from a climate change perspective in terms of transportation and greenhouse gases and transportation, about 20% or so– 20%, 25% come from the trucks. So it’s significant, and it’s actually the two that are going up– the really problematic ones are trucks and planes. We’re flying a lot more, and we’re using a lot more trucks to move stuff around.

IRA FLATOW: When we last spoke, you personally drove a hydrogen car. Do you still drive it?

DANIEL SPERLING: No, I let it go at the end of the lease. And what I’ve been practicing is being carless. I live in this little town, a college town of Davis, California. And we have a lot of good bike paths. And so, really, what’s changed in recent years is the availability of Uber and Lyft. So I know now I’m never going to be stranded anywhere. And that’s what makes it possible to give up my car.

IRA FLATOW: Well, let’s talk about that. With Uber and Lyft getting in greater usage, are we not just driving a car more, which we shouldn’t be?

DANIEL SPERLING: Well, the research shows that what’s happened with Uber and Lyft is they have led to a small increase in actual vehicle use. That there’s some reductions in the sense that people that had been using cars have switched– given up their cars like me. But there’s also some that were on transit and switched to Uber. Some were walking and switched to Uber and Lyft. So the net effect is a small increase.

But I think, for me– so I’m a big advocate of these new services because I think about it strategically. It’s like, to go in the future, to really reduce overall vehicle use, make our cities more sustainable, we really have to give up personal car ownership. And I know that’s a big leap. But the only way we’re going to get there is to create more choices for people, more good choices.

So Lyft and Uber [INAUDIBLE] and Via, and there’s some others– are really the opening of the door. It gets people accustomed to the idea of giving up their car, riding in strangers’ cars, sharing rides, and using an app to call a vehicle, all these things which were unacceptable, unavailable just 10 years ago.

IRA FLATOW: I want to move on to talk a little bit more about alternative vehicles and the adoption of alternative vehicles. I drive an electric car myself. And I really love it. I want to play a note that Robin from Texas sent in on our Science Friday VoxPop app about choosing a car.

ROBIN: Hi, I’m Robin. I live in Texas. I oftentimes will travel either to Big Bend or towards El Paso. El Paso’s 500 miles from where I’m at. Currently, there’s not an electric vehicle that can go that far. And it’s like 2 and 1/2 hours from a hospital at a certain point on the highway. So there’s definitely no electric chargers. We need longer distance.

IRA FLATOW: And Dan, is that one of the major problems of not having an electric society, where there are enough chargers around?

DANIEL SPERLING: It is, but in that case, it’s fast chargers because there are lots of cars now that will go over 200 miles. So for a 500 mile, you might need to do two charges. But you can do these fast– there’s fast chargers available now, and they’re building more and more of them. And it can– 30, 40 minutes to get a fast charge. And they’re designing new ones that will be even 10 or 15 minutes. I mean, at the end of the day, you shouldn’t be driving 500 miles without stopping, right? So it’s not such a bad idea to think that you are going to stop along the way.

IRA FLATOW: But if you drive a truck, a trucker is going to drive 500 miles without stopping. And we don’t have electric trucks yet. Can we design a truck, and is that sort of a sweet point, a sweet spot, to get a truck that can go 500 miles on an electric charge?

DANIEL SPERLING: Well, the sweet spot for trucks are the smaller delivery trucks, the UPS type trucks that are making deliveries in neighborhoods. Because they don’t drive very far in a day. It’s a lot of stop and go, and that’s where electric vehicles are really good, really soar. So that’s the sweet spot for trucks. Those long haul trucks are actually the most difficult ones to electrify.

So I’m also a board member for the California Air Resources board. And just yesterday, we started a process to require all trucks to become electric. And there’s going to be a phase in process. And it includes those big long haul tractor trailers. And it’s unclear exactly how this is going to play out. Because it can be batteries, it can be fuel cells with just hydrogen, and maybe even some clean biofuels.

IRA FLATOW: Our number, 844-724-8255. I want to bring in Rachel Muncrief, who’s deputy director of the International Council on Clean Transportation based in Washington. Welcome to Science Friday.

RACHEL MUNCRIEF: Hi, how are you?

IRA FLATOW: Let’s talk about the contribution of heavy vehicles. And we’re talking about trucks, long haul cargo trucks, and city buses, which account for half of the transportation-related emissions in the US. And if you look around, pretty much everything you see has been on one of those trucks, right?

RACHEL MUNCRIEF: Mm-hmm.

IRA FLATOW: You study heavy vehicles. How do we classify them? What are they?

RACHEL MUNCRIEF: OK, that’s a good question. Yeah, so I mean, I think Dan’s already started to talk about this. So heavy duty vehicles basically can range from anything to kind of like those big pickup trucks and vans through delivery trucks, buses, vocational vehicles, all the way to, yeah, tractor trailers, long haul tractor trailers, of when you look at that whole segment, all those different kinds of heavy duty vehicles, the tractor trailers by far are the ones that are sort of consuming the most fuel and emitting the most CO2. Of all of the heavy duty vehicles, it’s about 70% of the CO2 is coming from the tractor trailers.

IRA FLATOW: And what can we– what’s the easiest– what’s the low hanging fruit in the heavy vehicles?

RACHEL MUNCRIEF: Well, so the way I look at it is this. I mean, we have to focus on really decarbonizing the transportation sector if we want to meet our climate goals. And we know that no matter what we do and no matter how quickly we go towards zero tailpipe emission technologies, we’re still going to be selling a lot of internal combustion vehicles between over the next 30 years, let’s say. Some people say it could be like two billion or more internal combustion vehicles, cars and trucks.

So what we have to do is make sure that not only do we push to try to get these zero tailpipe emission vehicles out there, but we also have to make sure that the internal combustion vehicles that we’re selling are as efficient as possible. And there’s quite a lot of things that can be done today to improve the efficiency of trucks.

IRA FLATOW: Give me a couple.

RACHEL MUNCRIEF: OK. So if you’re thinking about a long haul tractor trailer, a lot of fuel is consumed by basically just trying to get that truck down the road. So if you can actually make that truck more aerodynamic, you could save quite a lot of fuel. If you can put on better tires on the truck, like lower rolling resistance tires, that also saves fuel. You can get more efficient engines that are currently being developed. And that also saves fuel. So basically, starting from a baseline of where we are today, there’s still probably about– I don’t know– at least 30% or 40% more fuel efficiency savings, just from doing these kind of conventional steps.

IRA FLATOW: Dan Sperling talked about California coming up with the mandatory truck standards. Do you think that regulations like those will help drive innovation?

RACHEL MUNCRIEF: Yeah, we have to have regulations like those. And California is the first one in the world to propose that. And I think if we don’t, the trucking industry is fairly conservative. If the truck makers don’t know that for sure they’re going to have to sell these new advanced technologies, then they’re not going to make the investments now. So I think it’s actually critical that we put in place these kind of policies to give certainty so they can make those kinds of investments.

IRA FLATOW: What about– talking about fully electric trucks, what about hybrid engines? Hybrid cars have been around forever. We see hybrid buses all the time. Why not push for more hybrid trucks?

RACHEL MUNCRIEF: Yeah. And like we’re saying, it’s really hybrids work best on a specific kind of driving. So the hybrids work the best when you have the kind of driving where you’re in a stop and go situation. Because that’s when you regenerate the battery, is during braking. So if you have an application which is a long haul truck that’s mostly driving on the highway that’s not braking a lot, the benefits from putting a hybrid on that truck are going to just be less than it would be if you put it on a bus who’s constantly stopping and going or a, yeah, urban delivery truck who’s stopping and going. So you just have to be smart about picking the right technologies for the right applications.

IRA FLATOW: Hm, that’s interesting because a person in a long range truck is never stepping on the brake very much, right? Not regenerating–

RACHEL MUNCRIEF: Yeah, not too much.

IRA FLATOW: Huh.

RACHEL MUNCRIEF: But you actually can still– there is still potential for hybridization in that because you can essentially– even though you might not be stepping on the brake, you are going up and down hills. And when you’re kind of going down a hill, you can recoup energy with the hybrid in that application as well.

IRA FLATOW: And that’s quite interesting. So the short-term trucks like the delivery trucks, they offer then the most– you said, as you said before, depending on the kind of truck, they would, as Dan said, the short delivery trucks would offer the most benefit for the bang– bang for the buck.

RACHEL MUNCRIEF: They would offer more, yeah, in benefit in terms of hybridization, but they’re also a really good candidate for just full electrification.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. I’m Ira Flatow. This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios, talking about green transportation with Rachel Muncrief and Dan Sperling. Dan, what do you think of what we’ve been talking about?

DANIEL SPERLING: Yeah, I think Rachel is exactly right. The one thing I’d add is that– well, I would note that the diesel engines in trucks is a remarkably efficient power plant. And so another idea on top of everything we’ve been talking about is finding some of these very low carbon biofuels that could be a liquid that could be used to replace the diesel fuel. And so in that, we’re developing diesel engines also that have lower pollutants criteria, what we call criteria pollutants, [INAUDIBLE] and particulate matter. And so I think that’s an option we have to seriously consider–

IRA FLATOW: Rachel, before I let you go–

DANIEL SPERLING: –for the long haul trucks.

IRA FLATOW: We often ask guests for something the average listener can do to have some effect. Rachel, is there anything you can suggest to those of us who don’t own or drive a big truck?

RACHEL MUNCRIEF: Sure. I mean, like you said, pretty much, if you look around you, every single thing that you’re probably looking at has been on a truck at some point– your computer, your coffee cup, whatever it is. So I mean, one thing you can do– I know this isn’t really a good message for this time of the year in December, but maybe you could buy less things. So therefore, you’d have less things that were transported on trucks. Or you can think about buying things that were sort of made locally, so they have less distance to go on trucks. Some websites offer the option of a sort of a slower delivery time. That’s another option because that gives the shipper a chance to ship things slightly more efficiently.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, and if you order five things on Amazon on five different days, it’s five different trips. If you order it all on one day, save it up. You’ve got one trip there.

RACHEL MUNCRIEF: There you go.

IRA FLATOW: OK, Rachel, thank you very much. Rachel Muncrief is deputy director of the International Council on Clean Transportation based in Washington. Thank you for joining us today.

RACHEL MUNCRIEF: Thank you.

IRA FLATOW: Dan, do you have anything to suggest to our listeners, what they might do for stuff that is this holiday season or to do with shipping and trucking?

DANIEL SPERLING: Yeah. Well, I would take it even further, what Rachel was just saying. Because, actually, what we’re seeing is that people are demanding the delivery of these goods faster and faster. And it’s encouraged by Amazon. I call it the Amazon Prime effect. And so now Amazon is actually shifting to one-day delivery. That’s what they’re aiming for. And the result of that is they’re building all of these warehouses and distribution centers everywhere. And they’re sending out many more shipments in smaller amounts, many more trucks going through neighborhoods.

And so this is an example of where we’re actually going in the wrong direction on many ways. And there was a comic strip back in the old days in the ’70s, Pogo, and one of the lines was, I have seen the enemy, and he is us. And so I guess this comes back to the message you want to communicate to people is that if you’re going to order things, order them, as you were saying, as a cluster of goods, all of them at once. Or don’t require them or ask for them to be delivered quickly. That way, they can package them all together and make bigger deliveries and fewer truck trips being made.

IRA FLATOW: Our number, 844-724-8255. We’re talking about green transportation. We’re going to take a break. I want to come back and talk, Dan, with you more about in Europe and China, when they want to go someplace, they build a railroad. We haven’t built railroads in years. And there are a couple of things on the drawing boards about railroads, and maybe we should talk about them and talk about what is so resistant in this country about building railroads, instead of more airports. So our number, 844-724-8255. You can also tweet us at @scifri. We’ll be back with Dan Sperling and anoter guest after the break. Stay with us.

This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Continuing with our Degrees of Change series, I’m talking with Daniel Sperling of University of California, Davis, founding director of the Institute for Transportation Studies. We have, as you can imagine, lots of calls coming in and tweets. Let’s see how many we can get in. Let’s go to Troy in Phoenix. Hi, welcome to Science Friday.

TROY: Hi, Ira. How are you today?

IRA FLATOW: Fine, how are you? Go ahead.

TROY: Yes. I was calling in. I drive an electric car, and I also have a reservation for an electric truck. I own a delivery business, and I currently use an Isuzu NPR type delivery truck, kind of like the bigger FedEx and UPS truck. And I’m currently spending about $1,000 to $1,200 a month in fuel for that vehicle. And with the electric truck and charging it during the day, I also have solar panels on my roof, charging that truck with very little help from the grid. That more than covers the note for that truck, so the return on investment on an electric vehicle for a delivery business is very fast. And it’s a almost no-brainer [INAUDIBLE].

IRA FLATOW: Thank you. That’s a great comment. Dan, there must be a lot of people like him, waiting for their electric trucks to come out.

DANIEL SPERLING: Well, that’s what Elon Musk thinks with his new Cybertruck. I don’t know if you saw that, but it’s true. But there are. There’s a number of companies now really planning to roll out some electric pickup trucks. And I think there is a big market because, indeed, you say the electricity costs for operating these vehicles is much less than the gasoline or the diesel that you use in it.

So even though for now, the truck still costs more– the electric trucks– the battery cost– the big story in vehicles is, battery costs are coming down so fast. They’ve come down– they were like $1,200 per kilowatt hour 10 years ago. Now they’re about $200. So that’s six times– it was six times higher. And all the port forecasts are it’s going to continue coming down. So that means that, really, the future of battery vehicles, whether it’s cars or trucks, is really very promising.

IRA FLATOW: Here’s a tweet from Jessica, who says, I would love to reduce my carbon footprint by taking Amtrak. But this isn’t feasible on my schedule. How can we increase awareness and viability of rail travel, when so much of our infrastructure has been hostile towards such efforts? Is it possible, Dan, do you think, to resurrect rail travel? And you hear about efforts in California between San Francisco and LA going and having trouble getting going. I just heard the other day that they’re talking about Portland, Oregon and Seattle coming out. Has rail got any lifeblood left in this country?

DANIEL SPERLING: Well, maybe a little. But the reality is that this country 100 years ago started down the path of cars. We built our cities around cars. So all of our modern– all of our 20th century cities are all sprawled. Our suburbs and even in the older cities are sprawled. And that just is not very conducive for using rail transportation. And we have so many cars, and land use is so diffuse. So it’s really a tough sell. I was just in Europe, and I just love using the bullet trains there.

But it’s just going to be a tough sell. So I think what we’re looking at here is coming up with other ways of providing that intercity travel. And aviation is part of our challenge. But for the shorter trips, one of the longer term options are these automated cars that can be like vans. And they can be pretty inexpensive. They can be electric, so there’s no emissions. And that’s not tomorrow, but 10, 20 years, that could be one part of the solution.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s go to the phones to Brandon in Maiden, North Carolina. Hi, Brandon.

BRANDON: Hey, Ira. I’ve been waiting on this conversation for a long time. So I’ve got two questions. One, has anybody thought about battery degrade, how to store it, how to dispose of it? Because they have really toxic chemicals in those batteries. And I was just thinking about a car battery ended up in the dump and that leaching into the soil. And why haven’t we moved more towards, like, compressed hydrogen vehicles? Because the only emissions from those is water. And it takes a lot less hydrogen to make the same amount of combustion that fuel and air make.

IRA FLATOW: All right. Good questions. Well, that gives me the opportunity to bring in another guest. Early in the hour, I mentioned Greta Thunberg sailing across the Atlantic Ocean because she didn’t want the emission burden that goes with air travel. Air travel, as a whole, contributes only 2 and 1/2% of the world’s carbon emissions. But any given flight can produce hundreds of kilograms of CO2 per passenger, with a large portion coming during the taxi takeoff and landing portions.

So what can be done to cut back on those emissions? Joining me now is Steven Barrett. He’s professor in the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics and director of the Laboratory for Aviation and the Environment at MIT. And he joins me by Skype from South Korea, where it’s around 4:00 AM. Thank you for staying up.

STEVEN BARRETT: Well, I didn’t stay up, I’m afraid to say. But I got up, and I’m glad to be with you, sir. Thanks for having me.

IRA FLATOW: Well, it’s great to have you. How carbon intensive is air flight?

STEVEN BARRETT: It kind of depends how you measure it. So it depends on the question. If you compare seat miles, so kilograms or tons of CO2 per seat mile, it actually looks pretty good and ends up being about the same as a really molten car like a Honda. So yeah, when you measure it like that, compared to a Honda of, say, an occupancy of two people, then it comes out to be the same. The difference is that a Honda doesn’t travel 10,000 miles through the night at 600 miles an hour. So when you look at it that way, the absolute numbers can be pretty high per passenger.

IRA FLATOW: I saw a pilot on YouTube talking about this. And he said that just in the taxiing on the taxiway, waiting to take off, and then the takeoff mode is a tremendous release of carbon dioxide and air pollution in that phase.

STEVEN BARRETT: Yeah, I mean, in absolute terms, it can be. It’s still probably only about 10% of the overall CO2 emissions of a typical flight. But to give you a sense of the scale, something like a Boeing 737 or an A320 on the takeoff [INAUDIBLE] engine power. Two engines, each are burning about a liter of fuel per second, so that’s, what, 2, 4 pounds a second, roughly, of fuel going into the engines on the takeoff [INAUDIBLE].

IRA FLATOW: And what about the news this week that there was a small electric plane being tested? It had its first flight, a seaplane.

STEVEN BARRETT: I think that’s a pretty exciting development. I mean, we’re seeing more and more electric planes for initially nation small range applications. But this is an important development because in the long-term, you would like to see aviation become more and more electric. And there are real challenges with making long haul flights electric. And it’s not even obvious if long haul flights could be made electric because of challenges with energy density and batteries.

But for short range flights and, for example, for urban air mobility or air taxis, then electric makes a lot of sense because it does seem like you could get flights that lost 30 minutes or an hour to be electric with something not too far off today’s battery technology. And this is a great step along that path. So it’s very exciting to see that development.

IRA FLATOW: What are some of the areas that your lab is looking at to make planes more carbon neutral?

STEVEN BARRETT: Well, one of the areas we look at is fuel. So I mean, really, you basically got a few options. You can either kind of fly the plane smarter, so they use less fuel. And that’s about routing more efficiently. But there’s only so much you can win there. You might get 5% or 10%. So that’s important to do, but there’s a limit to the scale of the benefit. The second thing is you could fly better planes, use less fuel. And a lot of aeronautics research, including some we do, is focused on designing aircraft of the future that would use less energy.

But the third would be having the same planes operate in the same way, but burning a fuel that’s intrinsically greener. And that would be biofuels that have a lower lifecycle carbon intensity. And we do a lot of work on assessing biofuels to provide impartial information to industry policymakers and the public on the carbon intensity of different fuel options.

IRA FLATOW: Are all planes in common use around the same air modern propulsion system? Or are they different? I know that people think that old jets are the same, but there are a lot of different kinds of jets. And some are more green friendly than others, are they not?

STEVEN BARRETT: They’re generally pretty comparable for a given generation. So if you take, for example, a 1990 design versus a 2010 design, that there’ll be a significant improvement there of perhaps you might say 20%, something maybe 25%. But the main competing manufacturers, whether it’s Rolls Royce and Pratt and Whitney on the engines or Boeing and Airbus on the airframes, they do tend to keep pace.

But if you take a look at the long arc over the last 30 years and more, there’s something like 1.5% or 2% year on year improvement in the fuel efficiency of airplanes. And that’s been a long-term trend. And to sustain that over many years is kind of impressive. The problem is that aviation is growing at 4% or 5% per year. So that’s far outstripping the improvements in efficiency.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s see if we can get a phone call or tweet in before we have to go. Let’s go to Kristen in Manhattan. Hi, welcome to Science Friday.

KRISTIN: Hi, thanks so much for having me on. I was just looking online, trying to get some information on paying a voluntary carbon tax for air travel. And then your show came on. So maybe you guys can answer this for me. I’m recently retired and traveling now like I never have before. I just got back from Vietnam. I’m going to Peru in February. And I see beautiful Greta Thunberg, and I feel like a guilty– I feel terrible.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, let me ask our guest. Steve, can you pay a voluntary carbon tax? Or Dan?

STEVEN BARRETT: Yeah, I think that’s a wonderful thing to do for those who want to do it. I think the only thing to keep in mind is, one, is to make sure you research the integrity of the offsetting scheme that’s offered. And you can look up online reviews of the integrity of the scheme that’s being offered by a particular vendor. And the second is that in the long-run, I don’t think we can rely on kind of moralizing people to do the right thing. We ultimately will need some rational way of incorporating these effects into the economic system. And that ultimately really means a carbon tax or a carbon price of some kind. I think that’s where we got ahead, eventually.

IRA FLATOW: I’m Ira Flatow. This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios, talking with Steven Barrett and Dan Sperling about alternative transportation. We have a lot of tweets that have come in. John asks, why can’t they have batteries they just swap out like a battery in a drill for a long haul truck? This seems– I was talking about this before with my staff about this. A truck is– or even a train– if you make an electric train, you swap out the battery, the trains– it has a couple of days to travel. What’s an hour swap out going to take out of that kind of travel?

STEVEN BARRETT: I mean, in the context of airplanes–

DANIEL SPERLING: Well, it–

STEVEN BARRETT: I’m sorry. Is this the–

IRA FLATOW: Go ahead. You can go, Steven.

STEVEN BARRETT: Yeah. OK, in the context of planes, one of the good things about using a fuel is that as you fly, you’re burning the fuel. So the plane’s getting lighter. So for a longer range emission, it’s really beneficial to have a plane that gets lighter the further you go, because then it gets easier to go further. So that’s one of the reasons why batteries tend to look a bit better in the shorter range, because they’re very heavy anyway relative to fuel. And they get even heavier for an aircraft along the ranges. And then you’re not burning it up. So having batteries long range is difficult.

Then when it comes to swapping, if you want to swap, you have to have more structure in the aircraft to enable the swapping. So it would be a less efficient aircraft structure, which makes it heavier, which then means more energy. So it’s just a much more difficult thing to do for a plane than it would be for a ground vehicle.

IRA FLATOW: Dan, you have the last word here.

DANIEL SPERLING: Yeah. I mean, we are going towards electrification for everything except aviation. There are the exceptions with aviation for a short haul, but basically, we’re electrifying transportation. And I think that’s the future, and we’re trying to figure out exactly how. Part of that includes hydrogen fuel cells, which are electric, battery electrics. I don’t think swapping is going to play much of a role, but there’s fast charging technology that’s coming along.

And a lot of it’s on the individual perspective. We have to adjust a little bit. It is easy. Electric vehicles really are easy. It’s a lot easier to charge up at home than to go to a gas station. So a lot of this is people adapting to this new reality–

IRA FLATOW: All right.

DANIEL SPERLING: –that we’re going to be–

IRA FLATOW: Have to leave it there. Thank you, Dan. Dan Sperling, professor of Civil Engineering at the UC Davis, Steve Barrett, professor in the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics at MIT. And a reminder, we’re continuing our climate series of change each month. And if you want to get involved in our series, tell us what you think or what’s happening in your community. You can find out more at ScienceFriday.com/degreesofchange.

Copyright © 2019 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

As Science Friday’s director and senior producer, Charles Bergquist channels the chaos of a live production studio into something sounding like a radio program. Favorite topics include planetary sciences, chemistry, materials, and shiny things with blinking lights.

Lauren J. Young was Science Friday’s digital producer. When she’s not shelving books as a library assistant, she’s adding to her impressive Pez dispenser collection.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.