Meet The Scientists Reviving The World’s Fading Corals

33:16 minutes

This story is part of Degrees Of Change, a series that explores the problem of climate change and how we as a planet are adapting to it. Tell us how you or your community are responding to climate change here.

A quarter of the world’s corals are now dead, victims of warming waters, changing ocean chemistry, sediment runoff, and disease. Many spectacular, heavily-touristed reefs have simply been loved to death.

But there are reasons for hope. Scientists around the world working on the front lines of the coral crisis have been inventing creative solutions that might buy the world’s reefs a little time.

Crawford Drury and his colleagues at the Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology are working to engineer more resilient corals, using a coral library for selective breeding experiments, and subjecting corals to different water conditions to see how they’ll adapt.

Some resilient corals are still in the wild, waiting to be found. Narrissa Spiers of the Kewalo Marine Laboratory in Honolulu found one such specimen hiding out in the polluted Honolulu Harbor.

“No self-respecting coral would ever want to live there, [so] it’s sort of a hotbed of evolution,” Spiers says.

Other scientists, like Danielle Dixson of the University of Delaware, are experimenting with corals that aren’t alive at all—3D-printed corals. The idea, she says, is to provide a sort of temporary housing for reef-dwellers after a big storm or human damage. Dixson likens these 3D-printed structures to the FEMA trailers brought in after a hurricane.

“In order for rebuilding to happen, you need people to live there so they can do their jobs,” she says. “The same thing is true in a reef.”

Dixson’s team is experimenting with these artificial corals in Fiji, to determine which animals use them as housing, and whether they spur the growth of new live corals too.

Two huge challenges remain. For any of these technologies to work at scale, we need quicker, more efficient ways to plant corals in the wild, says Tom Moore, the coral reef restoration lead at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

“We can create the most super coral in the world,” Moore says. “But if we can’t swamp the system with them, it’s not going to work.”

Crawford Drury, the scientist who’s engineering corals at the lab in Hawaii, pointed out that none of this will work if we don’t act now to address climate change.

“We can’t create corals that can survive in a hot tub.”

As we were producing this chapter of Degrees of Change, we asked you on the SciFri VoxPop app to share your stories about how corals have changed over the years, too—and here’s what you had to say.

Andrea Corona, digital intern at SciFri, had this to say:

As a child growing up in Puerto Rico, marine wildlife and coral reef conservation was an everyday topic. My dad would take us snorkeling often, and there were many rules discussed before heading into the water. “We’re going into their world,” he would say, making sure to remind us not to touch, bother, or take anything out of its natural habitat. Today, when I return to these places I remember so bright and vividly in my memory, I notice they’re fading fast—but I’m hopeful that restoration efforts will bring back some colors into this fading, beautiful world.

If you are planning on taking a snorkeling trip anytime soon, there are a few things you can do to reduce your impact on these delicate environments.

To start, make sure to use reef-safe sunscreen free of oxybenzone and other harmful chemicals that can lead to coral bleaching. You can check this list of known pollutants and see if your sunscreen contains any known pollutants. You can also protect yourself from the sun in other ways, by wearing shirts, hats, or apparel. Behavioral ecologist Danielle Dixon suggests using rash guard, “that way you are not releasing any chemicals,” she says.

Another relatively easy thing she recommends is to avoid peeing in the water in heavily touristed reef areas. When you pee in the water, and everyone else does too, it increases the amount of nitrates and ammonia, affecting pH levels near you, and could make corals more susceptible to disease. Don’t pee in the water.

If you live near the coast, researcher Narissa Spies recommends doing what you can to lower local stresses. One way to do this is to reduce soil runoff, which is harmful for reefs. Not only does increased sediment and turbidity reduce light availability for coral and seagrass photosynthesis, it also smothers the organism. By planting grass or other ground cover in any bare spots in your lawn, you can make a big difference.

If you’d like to be more hands-on and involved in the conservation of reefs, you could volunteer your time to restoration efforts. There are plenty of ongoing projects accepting volunteers. “I would tell people to go on google, search, “coral reef restoration,” and you will be presented with a variety of organizations,” says Tom Moore, coral reef restoration lead at NOAA. Here’s some resources he shared with us: the Southeast Florida Action Network works with citizen volunteers to help report coral disease, the Office of National Marine Sanctuaries Volunteer Program, Protected Resources Volunteer Opportunities.

Because coral reef decline is one symptom in the larger illness of climate change, you can still have an impact even if you don’t live anywhere near the coast. By switching to renewable energy sources and reducing your carbon footprint, you are also helping.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Tom Moore is Coral Reef Restoration Lead for NOAA in St. Petersburg, Florida.

Danielle Dixson is a behavioral ecologist and an associate professor at the University of Delaware in Lewes, Delaware.

Crawford “Ford” Drury is coral biology research program manager at the Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology in Kaneohe, Hawaii.

Narrissa Spies is a researcher in the Kewalo Marine Laboratory in Honolulu, Hawaii.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

[TICKING]

This month’s chapter of our Degrees of Change series about the climate crisis is about a tragedy that’s unfolding out of sight underwater. It’s the worldwide death of coral reefs. Back in the day, I remember when I first learned to scuba dive. My first open water dive was in a reef in the Caribbean. It was so full of staghorn coral that this novice diver, me– we had trouble navigating the living coral antlers.

But I was very recently saddened to learn that the reef has since died, along with 25% of all the coral reefs in the world. And the deaths have not gone unnoticed. We asked you for your recollections. And here is some of what you had to say on the Science Friday VoxPop app.

MINDY: Hi. This is Mindy. I live in Hilo, Hawaii. I took a break from snorkeling when my son was born in 2005. And after not going snorkeling– I hate to say this– for three whole years, when I went back I went home crying, telling my husband half the reef has died. That was 2008.

Now in 2019, it’s hard to go snorkeling because I see so much of it is gone. And that’s what I’ve seen here in Hilo, Hawaii. 80% of our local reef looks dead to me. And it just makes me cry.

SPEAKER 1: It’s been a while, maybe 20 years, but I used to go snorkeling in Panagsama Beach in Moalboal on Cebu island in the Philippines. It used to be very beautiful, but the last time I was there it was all decimated, gray charcoal, and just absolutely nothing to see. Everything was dead. And as I surfaced, I found out why. The fishermen were throwing dynamite sticks in the water for fishing and blowing up the coral reefs.

SPEAKER 2: I have seen coral reefs dying. I took my family to a place that’s at the very bottom of Mexico, very close to Belize, about five years ago, a place called Xcalak. And we snorkeled. We went there to snorkel. And I had my young son. And he loved it.

And I saw at least 80%, 85%, 90% of the reef brown and gone. We definitely saw fish, but nothing like what I saw when I was working as a scientist in Belize. And I snorkeled the reef back in the early 1990s. It was amazing, colorful, beautiful, exquisite. I was quite sad. I wish we could do something about climate change and stop the warming.

IRA FLATOW: That was [? Caz ?] from Idaho, [? Avram ?] from Irvine, and Mindy from Hawaii on the Science Friday VoxPop app. And I’m sure some of you have your own stories like that. But this hour, we’re going to accentuate the positive, focus on some reasons to have hope. We’ll be talking with scientists on the frontlines of this coral crisis who have a lot of innovative ideas to offer. And if you have a question or something to suggest, or a coral story you’d like to share, give us a call– 844-724-8255, 844-SCI-TALK– or tweet us @SciFri.

Dr. Tom Moore is coral reef restoration lead at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in St. Petersburg, Florida. He joins us from the studios of WUSF today. Welcome to Science Friday, Dr. Moore.

TOM MOORE: How are you doing today, Ira?

IRA FLATOW: Good. Give us a quick snapshot of where we are in the health of the corals around the world.

TOM MOORE: Yeah. Unfortunately, it’s not been a story of positivity over the course of the last 20 years or so. In the mid-1980s or so, we started to see reefs around the world start to die off or at least show signs of coral bleaching. And coral bleaching is when a coral turns stark white after releasing all the algae that live in symbiosis inside it. And it’s that algae that provides that coral its color. And it’s that same algae that helps corals feed.

And so when the water temperatures get too warm, that algae gets released from those corals. And if they stay out of those corals for more than just a week or two, that bleaching quickly turns to death. And as we’ve seen warmer water temperatures around the world with increasing frequency, we’re seeing increasing frequency of these bleaching events.

IRA FLATOW: Are we talking about the corals that people see when they go snorkeling, the shallow water corals? Or are the deep sea corals dying off also?

TOM MOORE: We’re talking predominantly about the shallow water corals. The deep sea corals are certainly– they have some threats themselves, but the direct threats from climate change are predominantly with our shallow water corals.

IRA FLATOW: And you already have divers who were going out today, trying to patch reefs back together after storms.

TOM MOORE: Yeah. So actually, where we got our start when we were thinking about reef restoration to begin with about 20 years ago was really thinking about reef restoration to fix things that were broken– ship groundings after storms, things like that. And it was actually some techniques that we found while doing that type of work that led us to begin to say reef restoration and rebuilding of reefs actually may be a more viable option at a bigger scale.

IRA FLATOW: Give us an idea from a diver’s eye view. How do those repair missions work? What are the techniques?

TOM MOORE: Yeah. So the first thing to understand is actually a little bit about how corals reproduce themselves. Because what we’re trying to do with restoration is actually just speed up the natural reproductive process. And so corals reproduce in two ways.

One is sexually, where they release eggs and sperm, usually one night a year a few days after the full moon. And those eggs and sperm will cross with each other. But those corals have to be in really close proximity for that to happen. And so the more we’ve seen corals die off, the more we haven’t had them in that close proximity.

But the other way they reproduce is what we refer to as asexually. So the same way somebody that has a greenhouse may grow plants– when they break one plant, they break it into two or three. And they’re able to use those two or three plants to then repopulate somebody’s garden or repopulate a forest.

We can do the same thing with reefs. So we’ll take a small section of a particular coral. The staghorn coral that you talked about earlier is one we do quite a lot of work with in the Caribbean. And we’ll take that one coral, and we’ll break that coral up into, say, 20 pieces. Those 20 pieces will be suspended in the water column and what we refer to as a coral tree. And those 20 pieces, over the course of a year, will then grow from being maybe the size of your pinky finger to being the size of a basketball.

And so we’ll then take those basketball-sized corals and take them up from growing in an underwater coral farm, and we’ll put them onto a boat, and we’ll take them to our restoration site. When you get to that restoration site, you’re going to jump in the water with your basket full of corals, and you’re going to start swimming along the reef. And you’re going to look for a segment of the reef that needs restoration. Unfortunately, that’s becoming large swaths of the reefs today.

And you’ll actually then take that coral, find a nice place for it on the bottom, scrape off the algae that’s there, make sure things are right, just the same way you’d be planting something in your garden, and go ahead and reattach the coral back to the reef using either cement or an underwater epoxy. And then that coral will start to take hold over the course of the next year. It’ll regrow over that epoxy, and start to secure itself, and hopefully continue to flourish. And so we’re doing that now, not with just one, but hundreds to thousands across individual reefs.

IRA FLATOW: So you can zip tie it down. You can– it sounds like the guys walk through the aisles of Home Depot and bringing that stuff underwater.

TOM MOORE: Yeah.

IRA FLATOW: So the tools you need that would help, you find them in regular stores.

TOM MOORE: Well, so I like to joke that our coral reef biologists have become real experts at using PVC pipe, duct tape, and zip ties to get their work done. Unfortunately though, we need to do this work at a much larger scale than we’re doing it at right now. So we’re doing great work and things that are the size of a building to maybe even a little bit larger than that, but we need to get to a much bigger scale. And so to get to that bigger scale, we’ve got to stop using just duct tape and zip ties to do our job. We’re going to need to think a little bit more creatively and get some engineers involved in the conversation.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, I agree with you. I’d like to bring on another guest now who is using material science to tackle the coral crisis by 3D printing corals, 3D printing corals. How does that work?

Danielle Dixson knows. She is a behavioral ecologist, science children’s book author, associate professor at the University of Delaware in Lewes, Delaware. She joins us by Skype. Welcome, Dr. Dixson.

DANIELLE DIXSON: Hi. Thank you for having me.

IRA FLATOW: You’re welcome. You’ve been experimenting with 3D printed coral as a way to restore reefs. How does that work?

DANIELLE DIXSON: Yeah. So these are products that two of my master’s students have been working on, Emily Rule and Alex Good. And we’ve been taking just normal 3D printers that are available to anyone and using a biodegradable filament, and then 3D printing actual corals. So using an iPhone, you can take a lot of pictures of an actual coral skeleton, and then you can create a model through software that makes a print file that you can then print the actual coral.

So the benefit of this is it has a lot of structural complexity or lots of little holes for fish and other invertebrates to hide in. A lot of our artificial reef substrates that we put out now, like a sunken ship, or a bridge that’s been blown apart, or something like that, they don’t have a lot of small habitats for little animals. And by 3D printing the actual coral, you’re replicating the habitat with an artificial substrate. The idea behind it is that real coral will then settle on– real coral babies or coral spat will settle on the 3D printed coral and turn it basically into a coral so it becomes a scaffolding inside the reef eventually.

IRA FLATOW: That’s really interesting. You’ve talked about these 3D printer corals as the FEMA trailers for reef animals after a storm or a damaging event. Why is it important to keep them around?

DANIELLE DIXSON: Yeah. So I liken these to FEMA trailers. So when a big hurricane like Hurricane Katrina hit, it wiped away houses for people. And without FEMA trailers, people wouldn’t have been able to stay in the location and do their jobs to rebuild the New Orleans area.

Same thing happens with a reef. A reef is a very populated, dense area of animals. So less than 1% of our ocean surfaces are coral reefs, and more than 25% of the ocean animals actually live on that habitat. So lots and lots of animals live there. And when something wipes out the reef or wipes out structural complexity, those animals all have jobs that they’re performing, and they need to stay in that area to keep the reef going and to help recover it.

So I look at our 3D printed corals as temporary habitats, just like FEMA trailers are to people, where the fish can still do their jobs. So you can keep herbivorous fish there. And those are fish that eat algae. And algae can overgrow corals and cause more death. But if you keep the algae population down, then the coral population can start to increase. In no way am I arguing that we can 3D print reefs as a solution to climate change or anything like that, but it’s a tool in our toolbox that hasn’t really been conventionally tested and along with some of the outplanting measures that have already been discussed could be really beneficial.

IRA FLATOW: And we have a photo on our website at sciencefriday.com/coralcrisis of a brittle star that actually moved in to live on one of these 3D printed corals. It’s a really cool photo– sciencefriday.com/coralcrisis. Let me get to the phone, see if I can get a phone call or two in. Let’s go to Tallahassee. Marcos, welcome to Science Friday.

MARCOS: Hi. Thank you for taking my call.

IRA FLATOW: Sure. Go ahead.

MARCOS: Well, first I just want to say thank you to your guests for all the work that they’re doing. I think it’s fantastic. I just had a quick question. From what I’ve read, and heard, and seen in documentaries is that another cause of coral reef destruction is ocean acidification that’s caused from the animal agriculture industry. And I was just wondering what you guys think about that.

IRA FLATOW: Dr. Moore, what do you think?

TOM MOORE: Sure. So I’m not very familiar with the topic of ocean acidification from the animal agriculture industry, so I’ll actually kick that to Danielle and see if she’s got some background on that.

DANIELLE DIXSON: That is actually what most of my research actually focuses on, is ocean acidification. I specifically look at how ocean acidification affects the behavior of animals. And I was part of the first group to actually show that fish are impacted quite heavily by ocean acidification. So what happens to a fish when they’re raised in future ocean acidification levels is they become more bold. So they spend a lot more time away from their habitat. And coral reef fish generally like to stay in their habitat.

They also have a problem detecting, understanding sensory signals. So, for example, a fish currently, under current conditions, if I give it the smell of a predator versus the smell of a non-predator, it can tell the smell of a predator. And it stays away from that water that smells like a predator.

Fish under ocean acidification conditions can’t distinguish between a predator and a non-predator. So it’ll spend equal time in either water choice. And as a result, we’ve seen five to nine-fold increase in mortality in fish that we’ve treated with ocean acidification versus fish that we have not.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. I’m Ira Flatow. This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios, talking with Danielle Dixson and Tom more about the question about the ocean acidification. That’s really an interesting question about the acidification. Because we just hear about the oceans getting warmer, and we don’t realize that the carbon dioxide is like a sink for the ocean. And it turns the ocean more acidic.

TOM MOORE: Yeah. That’s one of the things that as we think about how we do reef restoration, it’s actually becoming a bigger challenge. Because we rely on good ocean chemistry to allow corals to actually calcify, to accrete, to grow. And so as we have increased ocean acidification, we’ve got the potential that the corals that were either in growing in restoration or the corals that are naturally on the reef are becoming more brittle.

IRA FLATOW: Danielle, how much do you think that 3D printed corals will make an impression in the coral reefs? How much of a chunk of it can we hope for?

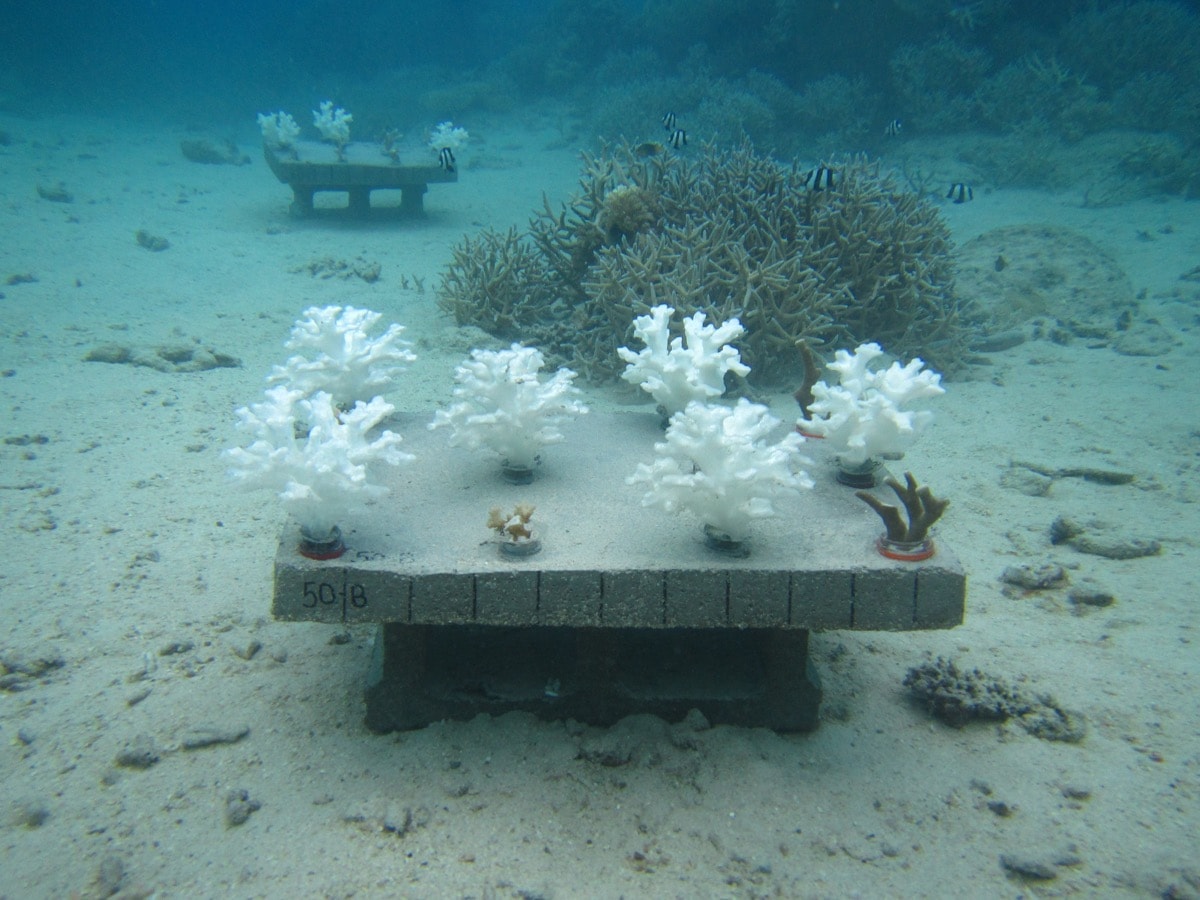

DANIELLE DIXSON: We’re currently doing research on that right now. So we have 3D printed experimental plots out in Fiji. And we have them at different mixes with live coral. So we have some that are 100% 3D printed, some that are 100% live. And then we have mixes of 50-50, or 75-25, or 25-75. And we’re trying to investigate how the 3D printed coral actually interacts with live coral and how the animals interact with it as well.

So right now I can’t really predict the extent that we could use it. But I think given the fact that a lot of people have 3D printers available to them, one of the ideas behind the project that we started was schools have 3D printers available to them. So this could almost be an outreach project where you supply the schools with the filament, and then they can print for you, and then you can put them out on the reef or things like that. Because putting them out is the easy job. Printing them takes time. But hopefully we’ll know more soon on the extent that it could be used, especially in conjunction with some of the other outplanting work. So you’d print some corals, outplant some live corals, and then you hopefully could keep a functioning reef happening while the reef rebuilds itself.

IRA FLATOW: All right. That’s quite interesting. Thank you, Dr. Dixson, for taking time to be with us today.

DANIELLE DIXSON: Thank you so much.

IRA FLATOW: Dr. Danielle Dixson, a behavior ecologist and associate professor, University of Delaware in Lewes, Delaware. And we have pictures of her 3D printed corals and her team working underwater– pictures up on our website at sciencefriday.com/corals. Check it out.

We’re going to come back and talk more about restoring corals after the break. If you have a question about how we’re bringing corals back, give us a call– 844-724-8255. One question that I want to ask– and I see phone calls are coming in– what can you do? What can you do as an individual to help solve the coral crisis? We’ll talk about it after the break. Stay with us.

This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

It’s the latest chapter of Degrees of Change, our series about how we, as a planet, are adapting to climate change. We’re talking this week about corals and some of the innovative ways scientists are tackling the worldwide die off of corals. Still with me is Dr. Tom Moore, coral reef restoration lead at the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration in St. Petersburg, Florida.

I want to go to the phones, Dr. Moore, because you were talking about coral reef restoration. And I want to go to Blake in Kentucky with an interesting question. Blake, hi. Welcome to Science Friday.

BLAKE: Hi. Thank you for having me on. My question is this. I am actually and have been for a long time a coral enthusiast in the hobby section. And my question is, for biodiversity, I know there are giant networks of hobbyists. And I wonder if that can be used on the aspect of scale.

IRA FLATOW: That’s a good question. As someone who used to grow corals in my home aquarium in my living room, I want to hear the answer. Can we crowdsource this out, people growing corals for a hobby?

TOM MOORE: That’s a great question. So it is something we’re starting to have some conversations about, about how we can incorporate the hobbyist industry and community in this. Because they know some of the most about growing corals than anybody else out there.

And so there are some challenges. We’ve got to think about biosecurity and making sure that the corals that would be grown, if they want to be reintroduced to the wild, that those are completely safe and healthy corals, that they don’t harbor any diseases or things like that. And that can be a big challenge, because coral disease is one of the other big threats that’s happening to reefs around the world. And so we’ve got to be careful we don’t reintroduce those.

But one of the places that I actually think the hobbyist community can help us the most with is think about some new techniques for both growing corals and, in particular, planting them on the reef. So actually, the growing in the underwater farms is a relatively straightforward process. We’ve gotten pretty good at it over the course of the last 15 years.

Where we have a lot of challenge and what really slows us down is actually getting those corals to the reef we want to plant them at and physically planting them on the reef. When you think about the scale of this problem, we’ve got to work at such large scales that things that take even a minute, if they could take 10 seconds, that thing could be 10 times faster. And so where the hobbyist community, I think, can help us is starting to think about some new tools that will allow us to plant those corals much faster on the reef.

IRA FLATOW: I’d like to bring on another guest now who’s working to engineer corals that are better able to withstand warmer waters by using a coral library in the lab. Dr. Crawford Drury is the coral biology research program manager at the Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology in Kane’ohe, Hawaii. He joins us from Hawaii Public Radio. Welcome to Science Friday, Dr. Drury.

CRAWFORD DRURY: Thanks for having me. Happy Friday.

IRA FLATOW: Happy Friday to you. You’re trying to breed supercorals. How do you do that?

CRAWFORD DRURY: All right. So we are trying to have a way to develop some tools and be really forward facing for the climate issues we’re dealing with. So we use the assisted evolution framework in our work that largely revolves around selective breeding and conditioning or stress hardening corals. So–

IRA FLATOW: Go ahead.

CRAWFORD DRURY: Actually, we have this biological library, like you mentioned, of individual coral colonies that we have been following for years. We tag them. We know how they behave. We know a lot about their history. And then we can go out and collect from those corals, and breed them to create a next generation that is more thermally tolerant.

IRA FLATOW: And how easy is it to substitute the newer, better breeds that you’re coming up with, the ones that are there now?

CRAWFORD DRURY: So a lot of our research right now is focused on understanding how this might be a tool and also the basics of the stress response, the biology and ecology of it. We do have an eye toward substituting these in actual restoration activities in the future. And we’ve just started a project doing this. But there’s a lot of trade-offs and other aspects of this process that we need to understand.

IRA FLATOW: We know that corals lose their symbiotic algae when the ocean changes. Can you switch out the algae that they need for a harder species that you’re looking into?

CRAWFORD DRURY: Yes, that can happen. There’s a lot of people doing really awesome research at University of Miami and elsewhere, looking at trading out different types of algae for those that are more thermally tolerant. And we have seen that that does make a difference in the coral downstream.

With our work on selective breeding, we’re also focusing on the host animal. So we know that if we take those parents and cross them, we can actually produce an offspring that is more thermally tolerant. And in the future, we have an eye toward potentially combining these different strategies in an additive way.

IRA FLATOW: Dr. Moore, let’s say that we are able to do a lot of these things, and we come up with creative solutions. Are we going to be able to save the coral, or are these like band aids, if we don’t do something about global warming, a global crisis climate change in the long run?

TOM MOORE: Yeah. I’m glad you asked that question because it really is the underpinning of everything we’re doing here. We’re trying to stabilize a system. We’re trying to stabilize a system that in many cases has seen upwards of 90% decline.

But we’re stabilizing that system for, ultimately, a planet that starts to stabilize itself. And so we believe we can buy time, and we can make sure we still have corals on the reef, but ultimately we’re never going to be able to restore every single reef out there. We have to set up a system to allow the reef to eventually recover itself as ocean conditions hopefully begin to stabilize into the future, even if those are warmer conditions. Because as Crawford was talking about, we’re hoping to be working with corals that will be a little bit more hardy over the course of the next 50 to 100 years.

IRA FLATOW: And thinking of hardy, my last question to you, Dr. Drury– do you think there are coral species hiding out there that are still doing really well and we just haven’t found them yet?

CRAWFORD DRURY: There definitely are. And there are some that we also know about. And harnessing that resilience as a way to study and also to restore reefs is going to be something really important moving forward.

IRA FLATOW: Well, thank you very much, Dr. Drury, for joining us. Crawford Drury is a coral biology research program manager at the Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology in Kane’ohe, Hawaii. Thank you very much.

CRAWFORD DRURY: Thanks.

IRA FLATOW: Next up, we have another story from Hawaii, a tale of a super hardy coral surviving in one of the least pristine places in the Hawaiian Islands. And then we’re talking about Honolulu Harbor. Here with that incredible story is Dr. Narissa Spies, a researcher at the Kewalo Marine Laboratory in Honolulu. She also joins us from Hawaii Public Radio today. Welcome to Science Friday.

CRAWFORD DRURY: Aloha, Ira. Thank you for having me.

IRA FLATOW: You found one of these resilient coral species in Honolulu Harbor. It’s probably one of the least pristine places in Hawaii, right?

NARISSA SPIES: Oh, definitely. It’s disgusting water most of the time and not a place one normally looks for healthy coral reefs.

IRA FLATOW: And did you specifically go looking there because you thought you might find one in a disgusting place?

NARISSA SPIES: No. It was a complete accident, actually. Back in 2013, Hawaii had a molasses spill in Honolulu Harbor. It’s a byproduct of their sugar industry. And it’s shipped to the mainland to make cattle feed. And this molasses just covered everything in the harbor, killed about 26,000 fish and a countless number of invertebrates.

And the researchers in my lab were among the first to do surveys. And we found that there were actually corals there. Some of them were 70 plus years old. Unfortunately, they didn’t make it, but there were corals that did survive. And a couple of those are the ones that I study, that show a great amount of resilience towards a number of stressors.

IRA FLATOW: And Hawaii is in another bleaching event right now, isn’t that right?

NARISSA SPIES: That’s correct. We went under a bleach watch back in early June, I believe, and went up to a level two bleach warning, which means things are likely dying out there. And as of this morning, I believe we’re back down to a watch, but still that’s a prolonged amount of time that these corals have had to survive without their symbions.

IRA FLATOW: And this resilient coral species that you found in the Honolulu Harbor, are we able to take them and have them reproduce out into other places?

NARISSA SPIES: That is our hope, actually. When I first discovered that this might be something that was completely new to science, I reached out to biologists with Hawaii’s Division of Aquatic Resources. And they actually have a coral farm here in Hawaii. And that is exactly what they’re doing. They’re microfragmenting corals with hopes to place them out on the reef.

IRA FLATOW: One of our producers, Christie Taylor, recently sat down with the president of the Marshall Islands, Hilda Heine, to talk about climate change. And here’s what she had to say about corals there and her country’s ability to assess the extent of the problem.

HILDA HEINE: It’s lack of resources that is holding the plan from going forward in terms of a national assessment on coral impacts. We know that it’s happening. We’ve seen it in some places, but we haven’t been able to do a comprehensive assessment of the extent of the problem. So corals are the breeding grounds for our marine resources. If the coral go, then a lot of marine life will also go with them.

And we depend on the marine life to sustain ourself. They’re food for us. But at the same time, coral is also needed to grow the islands. Without coral, the islands will not be there. So we need to make sure that that doesn’t happen.

IRA FLATOW: Tom, what are we doing to help the most affected nations, like Pacific island nations, to assess and address this issue?

TOM MOORE: Yeah. So this is a super complicated issue. And it’s an issue that, as you noted in the top, that is often out of sight for a lot of people. And so even right in the shoreline, you may be looking out at that beautiful sunset and not realize the crisis that’s happening underwater.

So we are focused on trying to provide better tools to help people assess the impacts out there, but also to plan for larger scale interventions. So one of the things that we’ve started to do over the course of this last year is really define large-scale restoration strategies. Historically, when I was asked how much we need to do, the answer was always, we need to do a lot. And how much do you need? We need a lot more than we have.

But that wasn’t really making much progress for us in terms of getting additional resources, like the president was saying we need. And so one of the things we’ve started to do is really try to define these big strategies. So in actually about two weeks, we’re going to be releasing a comprehensive restoration strategy for the Florida Keys. And we hope that that is the first of a number of restoration strategies that will ultimately develop and really clearly define exactly what is needed at a particular set of reefs. And so if folks are interested in learning about that Florida Keys strategy, please follow NOAA on social media. And we’re going to be talking a lot about it in about two weeks.

IRA FLATOW: Well, let’s begin talking about what people can do. We always like to end these segments with a look at something our listeners can do to help solve this problem. Tom, what would you suggest?

TOM MOORE: Yeah. So the first thing everybody can do is make sure people understand that this is a problem. Make sure your friends understand this is a problem. Make sure your elected officials understand that this is a problem. But beyond that, we have a lot of organizations that are literally out there working on the reef every single day, day in and day out. And those organizations need support financially, but they also need support in terms of manpower and divers.

So if you’re a person that’s going to take a vacation to a coral reef environment, do a little Google search beforehand and see who’s doing restoration in that community. Many of our partners are actually starting programs that allow you, as a diver coming from anywhere, to engage, and get in the water, and actually help out with the work. So it may be cleaning some algae at a coral farm. It may be planting corals out in the reef. But there’s a lot more opportunities that are there to get involved.

IRA FLATOW: I’m Ira Flatow. This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. I know as a snorkeler and diver that people do not heed the danger. They themselves are threats. I remember watching people standing with their snorkels and fins on top of a beautiful coral reef and wrecking it. Hobbyists and tourists do a lot of danger to coral sometimes, don’t you? What are they doing wrong, Tom?

TOM MOORE: Well, so I think that there’s a lot of things here. So it’s important that we have balanced use. We don’t want to find ourselves in a situation where we’re telling people they can’t go see these amazing resources. We want them to be able to go see those resources, but we want them to do it in a responsible way.

So one of the things in some of our areas that have strong marine protections, things like the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, we’ve got vessels that are certified to go and take divers to the reef in a very responsible way. And so we encourage people to go and go out with those Blue Star operators that are already certified as being able to interact with the environment in a responsible way.

IRA FLATOW: And that means don’t take a leak in the water. I mean, if you’re on a reef you can upset the chemistry of the water. And the corals will feel it.

TOM MOORE: You certainly can. And it’s important to think about it at that scale, but many times it’s actually more important to think about that leak you might be taking on land and the million other people that are doing that as well, and making sure that you’re in a community that has a well-maintained and advanced septic system– or not septic system, but sanitation system. Because even in some of our biggest cities, we’re unfortunately discharging not so clean water out onto the reef.

IRA FLATOW: And Narissa, just in the closing seconds, what would you suggest?

NARISSA SPIES: I agree. We need to reduce as many local stressors as we can. And that includes personal responsibility, things like wearing proper sunscreens. There are a number of sunscreens, things like oxybenzone, that have shown that they do cause damage to corals. So, for example, I no longer use sunscreen when I go in the water. I wear a UV protectant rash guard.

IRA FLATOW: That’s a great idea. I’d like to thank both of you this hour– Narissa Spies, researcher at Kewalo Marine Laboratory in Honolulu, and Tom Moore, coral reef restoration leader at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in St. Petersburg. Thank you both for taking time to be with us today.

TOM MOORE: Thanks, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: You’re welcome. We have pictures up of all the work that you heard about this hour on our website at sciencefriday.com/coralcrisis. We want to thank Lauren Young and Andrea Corona from our digital team for helping put this chapter of Degrees of Change together. You can read Andrea’s personal story about coral up there too at sciencefriday.com/coralcrisis.

Copyright © 2019 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Christopher Intagliata was Science Friday’s senior producer. He once served as a prop in an optical illusion and speaks passable Ira Flatowese.

Andrea Corona is a science writer and Science Friday’s fall 2019 digital intern. Her favorite conversations to have are about tiny houses, earth-ships, and the microbiome.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.