Marie Curie And The Women Scientists Who Became Her Legacy

17:33 minutes

When you consider someone’s legacy in science, you might think about their biggest discovery, their list of publications, or their titles, awards, and prizes. But another kind of scientific legacy involves the students and colleagues that passed through a scientist’s orbit over the course of a career.

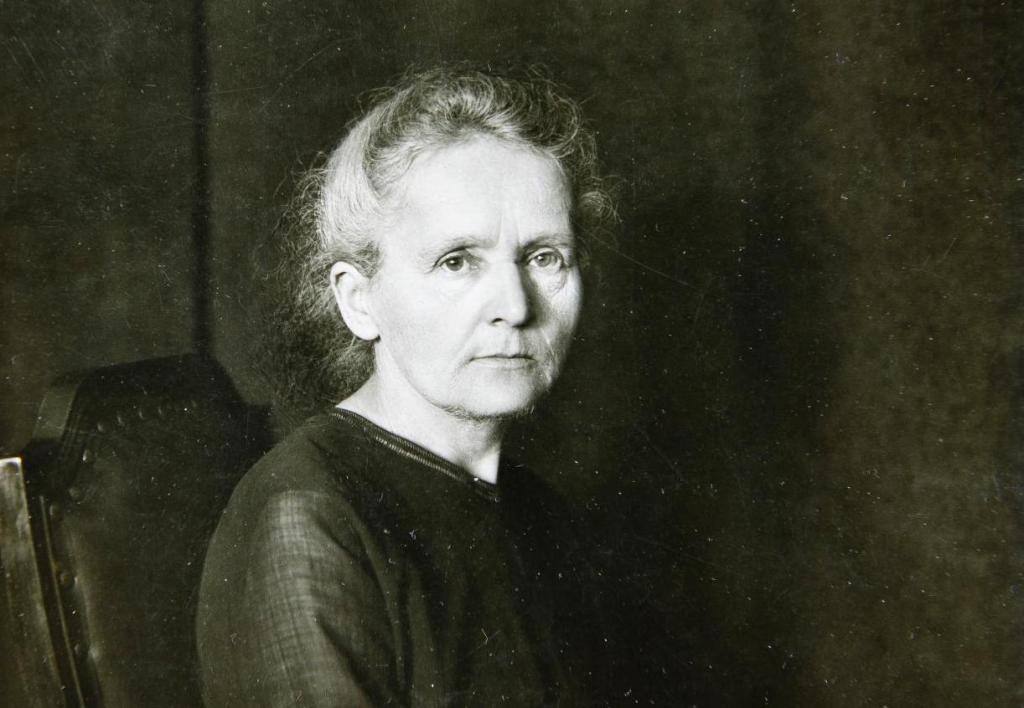

A new book, The Elements of Marie Curie: How the Glow of Radium Lit a Path for Women in Science, takes a look at the legacy of Madame Marie Curie, one of the most recognizable names in science history. But instead of looking only at Curie’s own life, author Dava Sobel views her through the lens of some of the 45 women who trained in Curie’s lab during her research into radioactivity.

Ira Flatow talks with Sobel about her research into Curie’s life, some of the anecdotes from the book, and how she interacted with some of her lab assistants and colleagues.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Dava Sobel is author of The Elements of Marie Curie: How the Glow of Radium Lit a Path for Women in Science. She’s based in New York, New York.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. When you talk about someone’s legacy in science, sure, you can talk about the big discovery, or their list of scientific publications. But another kind of legacy involves the list of students and colleagues that pass through a scientist’s orbit. A new book takes a look at the life of a familiar name in science, Madame Marie Curie. But instead of just looking at Curie’s own life, Author Dava Sobel views her through the lens of some of the 45 women who passed through Curie’s lab over the course of her career.

The book is The Elements of Marie Curie, How the Glow of Radium Lit a Path for Women in Science. I am delighted to welcome back Dava Sobel. Welcome back.

DAVA SOBEL: Thank you, Ira. I’m so happy to talk to you.

IRA FLATOW: It’s been too long. Let’s get right into this, because there’s so much to talk about. I love this book. So let’s talk about her being one of the most well-known figures in science. Why did you decide to write more about her?

DAVA SOBEL: Yes, she is the most famous woman in the history of science, but she was never the only one. And that’s the point. I decided to write about her when I learned about the 45 women who passed through the lab. That was something that I was sure no one knew about Madame Curie. And it felt like the right story for me in my very late coming to awareness of women’s issues in science.

IRA FLATOW: You write that the fact of her womanhood threatened her further advancement, given the popular perceptions of women’s place in society. It was easy for people to see Marie as merely Pierre’s wife, a dutiful assistant who made no independent discoveries.

DAVA SOBEL: Yes, and she still suffers from that conclusion in some quarters today.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. But recognition eventually did come. And she used her fame to help other women scientists to rise up. Your book says Curie on the cover, I mean, but it’s so much more about all the women scientists who she met and who worked with her lab. I view her as being the promised land for women–

DAVA SOBEL: Yes.

IRA FLATOW: –as students and colleagues. How did they all meet? Did she go after them? Did they find her?

DAVA SOBEL: They found her because she got famous pretty early. In 1903, she and Pierre shared a Nobel Prize in physics. So she was the first woman to win a Nobel Prize. And the fact that she was a woman scientist caught a lot of attention. And she really achieved world fame at that point in 1903. And then Pierre died in 1906. And against all odds and all traditions, she was allowed to take over the lab where they had worked together. And also, to step into his teaching position at the University of Paris.

So now, she was really a beacon. She was the only woman in the world with that kind of position, head of a laboratory, professor on a science faculty. So the women came to her. There’s no evidence that she set out to make a place for women. But on the other hand, she didn’t turn them away.

IRA FLATOW: And after they worked with her, did they go on to do great things of their own?

DAVA SOBEL: Some of them did. Some of them went back to be the first female professors in their own countries, including the Netherlands, Hungary, Norway. So they came from all over the world. Not very much is known about many of them, which was a problem writing this book. Marie Curie did not have a secretary for a number of years. And so there were very scant records kept about who came and who went. But there’s enough to name 45 people.

And of those 45, maybe 20 have a rich record. And a few of them didn’t go on in science. The first one who came to her, Harriet Brooks, who came from Canada, actually left the lab and got married. And not only didn’t continue her career, but tried to make a case that women were ill suited for science.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, you say that. I was going to bring that up because let me quote from the book. “Harriet Brooks says, the combination of the ability to think in mathematical formulas, and to manipulate skillfully the whimsical insturments–” I’m going to try to get this right– “physical laboratory, a combination necessary to attain eminence in physics,” she writes, “is apparently one seldom met in women.” Why was she so different from everyone else?

DAVA SOBEL: I think she was trying to salve her own conscience. Having left, having been a pioneer in radioactivity, she worked not only for Madame Curie, she worked for a while for JJ Thomson at the Cavendish in England, and for Ernest Rutherford. So she was with all the greats. And she had great ability, so she was being offered fellowships to continue. But she chose to get married. And I think she may have felt some guilt about that, and so turn things around. That’s just a guess, though. I don’t claim that in the book.

IRA FLATOW: I was startled to learn that her career began in studying magnetism. Nothing to do with radioactivity.

DAVA SOBEL: Right. So there she was, a physics student at the Sorbonne. And one of her professors got her an outside paying gig to do a study for the French steel industry, trying to figure out which type of steel would make the best magnets. And it was in the course of doing that work that she met Pierre. Someone introduced them because magnetism was an interest of his, and he had studied it pretty extensively. And I love the fact that the French word for magnet is aimant. My French accent is terrible. A-I-M-A-N-T, which also means lover.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. Kidding.

DAVA SOBEL: So the magnetism brought them together.

IRA FLATOW: From your stories you tell, she was seen differently in France. Was it odd that Curie was accepted into all the major science organizations in other countries almost immediately, but not France?

DAVA SOBEL: Yeah, they never accepted her in the Academy of Sciences. And I think that’s more of an embarrassment for the Academy now than it was for her.

IRA FLATOW: Was it a cultural difference?

DAVA SOBEL: It was immutable tradition that they not– they had no women in any of the academies. So this was seen as a breach of tradition. And they even said that. But she had a lot of supporters in the scientific community who were very outspoken in her favor. But they didn’t have enough votes to get her in. And election of new members came up only when a previous member in that field of science died. So it wasn’t as though she was going to have another opportunity the next year.

IRA FLATOW: Was she viewed any more favorably in the US?

DAVA SOBEL: Oh, yes. She was a member of several important organizations, including the American Philosophical Society. And then people in America raised money for her to buy more radium for her lab. And she came to this country twice to accept those gifts. And in each case, received the gift from the President of the United States. So that was about as high an honor as one could expect.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. You write, “on the day after Christmas in 1898, Henri Becquerel informed the Academie de [INAUDIBLE]— I’m not going to pronounce it in French– “informed the Academy of the Sciences of the discovery of radium. Although Becquerel shared the Curie’s excitement, the news of the new element elicited little response outside a small circle of physicists.” Why was that?

DAVA SOBEL: People were really interested in X-rays. So the discovery of X-rays happened toward the end of 1895, and it was a giant phenomenon. I forget. I think there were 1,000 papers published on X-rays over the next year or two. And then Becquerel found these uranic rays a few months later, and he really couldn’t get anybody interested in them. But Marie Curie chose them as her dissertation topic. And from her point of view, it was a good thing that other people weren’t interested. She wouldn’t have any competition.

And while working on it, Becquerel showed that anything containing uranium emitted these mysterious rays. And the first thing she did was to test every other element to see if any of them emitted the same kind of rays. And she found that thorium did. So she started calling them Becquerel rays instead of uranic rays. But then she started testing various ores, and she found something else that was far more active. And she immediately guessed that there was another unknown element that was also radioactive. That was her term. And she was going to take this ore apart and find this other element.

IRA FLATOW: We look back on her work today with the power of everything we know now about the atom, radiation, the periodic table. But it’s amazing that a lot of this research was working under a very different set of assumptions. They didn’t even know about protons and neutrons.

DAVA SOBEL: Right.

IRA FLATOW: Right? And they’re doing all this based on atomic weight.

DAVA SOBEL: Right.

IRA FLATOW: That’s mind-blowing stuff.

DAVA SOBEL: Yeah. And you mentioned atomic weight. So today, if you look that up, you’ll get the definition, well, it’s the number of protons plus the number of neutrons. But they didn’t know about the components of the atom at the beginning. She was in on all those discoveries. And radioactivity was one of the phenomena that helped people see inside the atom.

IRA FLATOW: There are so many great details and surprising moments of the book that are like little nuggets. Like, I’m going across, I’m reading and I see a picture of Marie on a camping trip. And I read the text underneath it. It shows all these people. Marie is here. And then in the background, it says, Albert Einstein.

DAVA SOBEL: Right. They went hiking together in the mountains.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah.

[LAUGHTER]

How did you discover that?

DAVA SOBEL: Well, she was part of this elite group of physicists that were first called together in 1911. It was called the Solvay Council. And this rich industrial chemist, Ernest Solvay, who could afford to invite the top scientists in the world to come together in a room and talk about the most exciting developments. And he hand-picked them, or he had people hand-picked them. And she was the only woman in that room from 1911 until 1933. They met about every three years.

So at the first meeting there was Albert Einstein, one of the other hand-picked scientists. And they liked each other right away.

IRA FLATOW: And so he was a supporter of her?

DAVA SOBEL: Yes.

IRA FLATOW: I imagine an important supporter.

DAVA SOBEL: Yes. Especially when she was accused of having an affair, and the press just chewed her up.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. Go into detail on that. I don’t think anybody really knew the depth of that affair and what it did to her.

DAVA SOBEL: To her. Yeah. This was five years after Pierre’s death. Her partner in the affair was Paul Langevin, another physicist. A very good friend of both Marie and Pierre’s. And he had been crying on her shoulder about his unhappy marriage. And I think she thought he was really going to leave the marriage and that she would have another marriage like she had with Pierre, where they were not only very much in love, but they worked together and talked about physics together.

But he did not leave his wife. And the press labeled her a foreigner, a home wrecker. It was pretty ugly.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. There are so many great details that people don’t know about. Her role in the war effort. She was in the war.

DAVA SOBEL: Yeah. I think that’s my favorite thing about her, that as soon as World War I began, she realized that this was the first time it would be possible to X-ray wounded soldiers. And she immediately got someone to give her a car, even though she didn’t know how to drive. And she outfitted it with X-ray equipment, and convinced the Army to let her drive to field hospitals. And even to the front, eventually. And she outfitted about 18 or 19 of those mobile X-ray units. And she trained 150 French women to be X-ray technicians.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. And you write, of course, about the unknown dangers of working with radioactive materials. She and others often found– and I’ll quote the book, “the palms of their hands flaked and peeled in response to handling radioactive products. And the tips of their fingers hardened painfully for weeks or months at a time. These discomforts did not worry them or deter them from pursuing their science. In fact, the reported skin lesions aroused the interest of medical doctors.”

DAVA SOBEL: Yes. And radium, very quickly, became the cure for cancer. And it held that position for about two decades. Which is one of the reasons she’s regarded as a great humanitarian.

IRA FLATOW: How were you able to do research on this book all through COVID? It sounds almost impossible.

DAVA SOBEL: Well, COVID, of course, kept me from going to Paris, just as it kept everybody from going anywhere. And very fortunately for me, the archives on Madame Curie have been digitized. So you can go on the website of the French National Library and read even the most personal documents, including the journal of her grief that she kept for a year after Pierre’s death. The notebooks in which she recorded the developmental milestones of her two children. Everything is there.

So I had a wealth of material. And fortunately, I had been to Paris for other reasons at other times, and to Warsaw. So I had a sense of the places where she was. And what can I say? I was highly motivated.

IRA FLATOW: Did you find actual original handwritten notes from her that–

DAVA SOBEL: Yes. Oh, yes. The whole grief journal is handwritten. There are drafts of her letters with her corrections. And I only just a week ago saw actual letters that she had handwritten. I happened to be visiting the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia. And the librarian there had looked for any materials about her that they might have. And there were two letters, fully handwritten letters. I did suggest that they have someone go over those documents with a Geiger counter.

IRA FLATOW: [LAUGHS]

DAVA SOBEL: But it was such a thrill for me after seeing everything on the screen. And then there they were on pieces of paper.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. Dava, it’s a terrific book. It would make a great holiday gift, I think, to anybody who’s interested in history or science. Thank you for taking time to be with us today.

DAVA SOBEL: Thank you for inviting me.

IRA FLATOW: Dava Sobel, author of the Elements of Marie Curie, How the Glow of Radium Lit a Path for Women in Science.

Copyright © 2024 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

As Science Friday’s director and senior producer, Charles Bergquist channels the chaos of a live production studio into something sounding like a radio program. Favorite topics include planetary sciences, chemistry, materials, and shiny things with blinking lights.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.