The GoFundMe Healthcare Plan Doesn’t Work

16:54 minutes

Big celebrity crowdfunding campaigns often raise huge sums of money. Take for example, Mila Kunis and Ashton Kutcher, who recently raised $20 million in a week for Ukrainian humanitarian aid.

But these types of crowdfunding campaigns are outliers. Increasingly, crowdfunding in the United States is being used as an ad-hoc social safety net. Around a third of campaigns on the most popular crowdfunding site, GoFundMe, are to cover medical costs. And most campaign goals are modest—aiming to raise a few thousand dollars. Yet 30% of campaigns to cover medical costs in 2020 raised zero dollars.

Researchers from the University of Washington crunched the data on roughly half a million GoFundMe campaigns for medical expenses to get a better picture of which campaigns are more likely to get funded and which aren’t.

Ira speaks with Nora Kenworthy, associate professor of nursing and health studies, global health and anthropology at the University of Washington and Mark Igra, sociology graduate student at the University of Washington.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Nora Kenworthy is an associate professor of Nursing and Health Studies, Global Health, and Anthropology at the University of Washington in Bothell, Washington.

Mark Igra is a graduate student in the Department of Sociology at the University of Washington in Seattle, Washington.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. You’re probably pretty familiar with crowdfunding campaigns, right? And some raise huge sums of money in the aftermath of humanitarian crises, like this current GoFundMe campaign by actors Mila Kunis and Ashton Kutcher.

ASHTON KUTCHER: We want to give you a little update on our campaign to stand with Ukraine. We have raised over $20 million in less than a week.

IRA FLATOW: But big celebrity-driven campaigns? They’re outliers. Increasingly, crowdfunding in the US is being used as an ad hoc social safety net. Around a third of campaigns on the most popular crowdfunding site, GoFundMe, are to cover medical costs. And most campaign goals are modest, aiming to raise but a few thousand bucks. Yet, 30% of campaigns to cover medical costs in 2020 raised $0. Nada. Nothing.

Researchers from the University of Washington crunched the data on roughly half a million GoFundMe campaigns for medical expenses to get a better picture of whose campaigns get funded, and who’s don’t. Joining me now are my guests, Nora Kenworthy, Associate Professor of Nursing and Health Studies, Global Health and Anthropology at the University of Washington based in Bothell Washington, and Mark Igra, graduate student in the Department of Sociology at the University of Washington in Seattle. Welcome to Science Friday. Mark, there’s a really big disparity between who is able to reach their crowdfunding goals for medical expenses versus who’s not able to do that. Who is more likely to receive funding for their campaign?

MARK IGRA: Well, the people who are most likely to receive funding are two groups of people, either people who have a large social media following via TikTok, or Facebook, or something else, or people who are well-connected to people who have financial resources to fund the campaign. But for most people who need the funds the most are in neither of those groups.

IRA FLATOW: Why is that?

MARK IGRA: We tend to be connected to people like us. So people with more income tend to be connected to other people with more income. People with more education tend to be connected to other people with more education. And that goes geographically. So we know from data from Facebook that people who live in richer areas, like the Upper East Side of New York where median household incomes are over $100,000, tend to have friends in other neighborhoods where incomes are high.

But, for example, people who live not that far away in Harlem, where incomes are low, less than $40,000 median income, friends tend to be in other places where incomes are low, like the Bronx. And so the networks we have dictate the amount of resources that can be given to our campaigns.

IRA FLATOW: Nora, do people know this going in? I mean, what are people’s perceptions of how well they’re going to be able to fundraise when they put up a campaign?

NORA KENWORTHY: I think most people have an expectation of raising maybe a couple thousand dollars. People who are more affluent might have greater expectations of $10,000, $20,000. GoFundMe itself tends to encourage people who are setting up campaigns to actually set quite low goals for their campaigns, I think trying to kind of modulate some of the expectations that people bring to the platform.

But in our recent paper, we found that the median campaign for medical expenses in 2020 actually raised only $265. So I think it’s safe to say that is far below what people’s expectations are.

IRA FLATOW: Wow.

NORA KENWORTHY: Yeah.

IRA FLATOW: Wow, that’s shocking. You mean, could have $50,000, $100,000, you go to a GoFundMe, you expect to get a few thousand, and you wind up with a couple hundred.

NORA KENWORTHY: Right. And I think people who raise small amounts of money, sometimes that can still be meaningful support to them. But if we think about it in the context of the volume of people’s medical bills and health financing needs, it’s really a tiny drop in the bucket.

IRA FLATOW: And Mark, is that actually more common not to reach your crowdfunding goals?

MARK IGRA: Yes, it is much more common not to reach crowdfunding goals. In this last paper, we showed that when you find all of the campaigns that people start in medical crowdfunding, we found about a third of them received nothing. Maybe they were not being distributed. And then, only something like 7% received the full amount that they were asking for.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. That really is surprising, I think, to anyone who wants to start a GoFundMe campaign, especially about their medical expenses. Let me ask you, Professor Kenworthy, how did the two of you link up to work on crowdfunding research for medical care?

NORA KENWORTHY: Yeah, so both of us come to this project with our own interest in this phenomenon. I’ve been looking at medical crowdfunding since about 2015, I believe. And I came into it with an interest in how people leverage charitable systems to access care and the pitfalls and challenges of relying on charitable systems to provide care. And so my background is public health. And Mark’s is more the sociological side of things. So I’ll let Mark talk about how he comes into this project.

MARK IGRA: Right, well, my basic interest is altruism and people helping each other. So I came to this because I also have a background with software and statistics, and so it was a way to find out, on a large scale, how altruism works and how giving works.

IRA FLATOW: Were you shocked that your findings? Let me ask first you, Mark. Were you shocked about how few people really want to help other people fund their medical problems?

MARK IGRA: Well, I think I’d put it differently. I wouldn’t say that very few people want to help. We actually do find many, many millions of dollars are given, and there are hundreds of thousands of donations given. So I wouldn’t say that people don’t want to give. I think people want to give. The issue is that there’s not enough connection between the people who have the money to give and the people who need the money.

NORA KENWORTHY: Americans are actually, lots of research shows that Americans are very generous. One thing that we have written about recently is that GoFundMe is part of a complex social media attention economy in which there is just so much content competing for our attention and for our eyes and, in this case, for our dollars. And so there are really strong algorithmic influences over what gets seen and how content gets pushed to us.

And one thing that I think is really clear in the GoFundMe ecosystem is that more successful campaigns tend to be seen more often by people. And so the likelihood of even finding some of these unsuccessful campaigns is really low.

IRA FLATOW: So you’re saying, if I hear you correctly, GoFundMe decides what it’s going to push out to its viewers to find, and if you’re not one of those people you lose out?

NORA KENWORTHY: Yeah, like any social media company, there is far more information than any user could possibly consume from the site. And so they use algorithms, they use search engine features, to determine what users see. And they generally push out to users things that they think will generate the most interest. And in this case, probably the most donations.

MARK IGRA: We talked about GoFundMe pushing campaigns out, but really, most of the social media sharing is happening on these other platforms, and those platforms all have algorithms that filter what we see. So even though we feel like we are seeing a huge hose of information, we are only seeing a small fraction of what they have available. So there are choices being made for us about what we even see, and those can affect the outcomes.

IRA FLATOW: Could someone who needs donations game the system at all? Try to get more people aware of their GoFundMe campaigns? Because you see this all the time, people saying, I started a GoFundMe campaign, please go to the site and see if you have a few bucks you can give me? Does that help at all?

NORA KENWORTHY: Yeah, it can. One of the things that we have noticed in talking to highly successful crowdfunders is that it really helps to have a close team of people who have a lot of expertise in marketing, PR. Some of these campaigns where people have pushed really hard to get their message out there, they do see more success. But again, that’s also a reflection of the kind of privilege that might be embedded within their social network, that they have friends with this kind of social media expertise and maybe large followings on social platforms.

IRA FLATOW: This seems like a predominantly American problem based on our poor health care system. Do we see people in Canada or the UK relying on GoFundMe sites?

NORA KENWORTHY: GoFundMe is certainly popular in other countries, as are other kinds of crowdfunding platforms. And it’s important for us to recognize that the healthcare systems in places like Canada and especially the UK have also faced a lot of retrenchment of social network services through austerity policies. But I think there’s a fundamental difference in just the volume and scale of need that we see in the US.

If I was going to make a generalized statement, I would say in the UK, you tend to see a lot of crowdfunding for maybe experimental procedures that aren’t covered under the National Health Service, or people who are wanting to get care faster than they’re able to under the NHS. In the US, it’s simply a lot of very basic needs. It’s people who are being bankrupted by illness, and it’s people who do not have adequate health coverage or can’t afford their health coverage and therefore, can’t afford essential medical care.

IRA FLATOW: Now, I understand that about a quarter of Americans have donated to a crowdfunding campaign. How has this changed our perception of how people ask for assistance and who is worthy of receiving it, Professor?

NORA KENWORTHY: It’s such a good question. I think that our social participation in this new economy has, in some ways, normalized the idea that we should have a role in picking and choosing who has access to medical care. And I think it’s important for us to pay attention to what other kinds of health values that might be making less prominent. And most important, I think, is it’s occluding this idea that everyone should be deserving of health care, that everyone should have a basic level of health care that they are entitled to regardless of what they look like, or how many friends they have, or how deserving they are by these complex and often very biased social metrics of deservingness.

IRA FLATOW: Mark, when the pandemic first broke out, first few months of the pandemic, did it change what kinds of campaigns people were doing on the site?

MARK IGRA: Well, we saw at the beginning of the pandemic a big spike in people requesting both money for things like PPE and support for other people who were affected, but also support for themselves, for their businesses, for basic needs as the disruption was growing. But again, when we studied COVID crowdfunding, we found that many people were not receiving very much money or any money at all. And it turned out that once the government stepped in and started distributing funds to people, that was a much more effective way of dealing with the losses caused by the onset of the pandemic.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. Professor Kenworthy, what can be done to change how the crowdfunding system operates and people’s reliance on it to meet their basic needs and their perceived incorrect assessment of how easy it is to get that money?

NORA KENWORTHY: I think part of it is having conversations like this one, helping people understand what crowdfunding realities look like behind the surface of what we see on the websites. I think it’s also important, however, to recognize that I think there are a lot of Americans who see people crowdfunding for basic medical bills and are distressed by that and are not happy that that’s our system. And so we feel it’s really important to continue reminding people that there are big structural alternatives to crowdfunding, namely, expanding health coverage to more Americans as well as the kinds of safety net programs that we saw expanded, in certain cases, during the pandemic.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, fix the system. Fix the healthcare system, problem may get a lot less.

NORA KENWORTHY: And I realize that’s a big solution. So some of the other stuff that we’ve been talking about is the importance of having more transparency from crowdfunding companies about not just what the outcomes are of crowdfunding campaigns, but what kinds of algorithms shape what becomes visible and what doesn’t. What kinds of corporate decisions are they making about things that might influence the equity and fairness between campaigns?

IRA FLATOW: Interesting you’re bringing that up. A few weeks ago, we talked with Dr. David Satcher who raised the issue and said a lot of people think that health inequities is about finding the right doctor. It is so much bigger than all of that, and this seems to be just another case of that.

MARK IGRA: So I wrote a paper about differences in returns by race and ethnicity to crowdfunding. And what I found was that it was not that sharing was any different by race or ethnicity or the income of the area where the crowdfunding campaign was started, but it does seem to be the case that because we have this history of things like redlining and job discrimination that lead to lower financial capacity for Black and Hispanic Americans, the returns to campaigns started by Black and Hispanic Americans are lower. And so we can see this history of racism being reproduced in the kinds of social network-driven charitable efforts that we take.

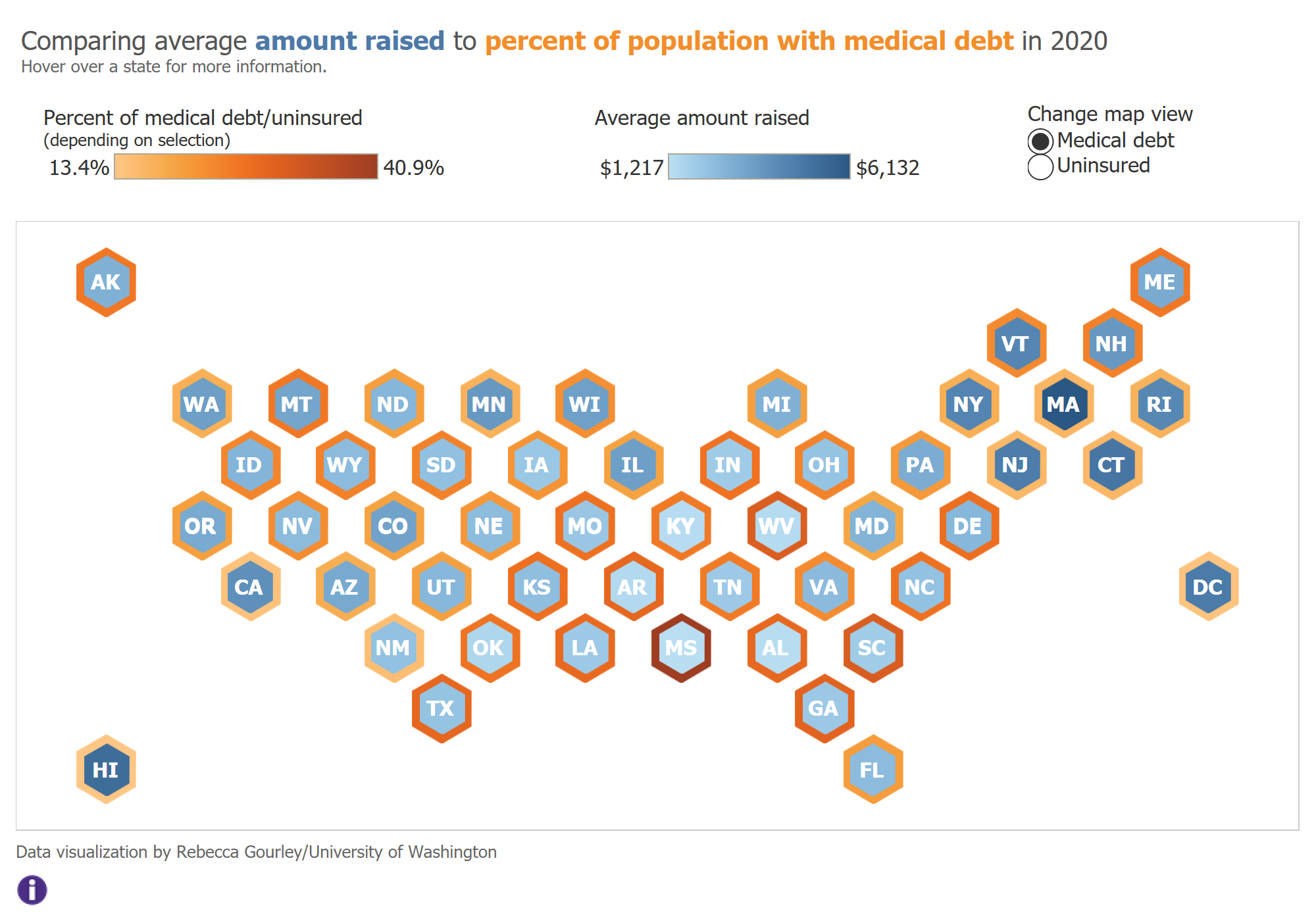

NORA KENWORTHY: Yeah, I think that’s a really important aspect of this research, which is observing the ways that crowdfunding can amplify or reproduce existing social inequities. And that’s something that we also put into this most recent paper. The places where people faced more medical debt and were less insured were also the places where they were raising the least amount of money. So we really feel that there are important dynamics that need further exploration here about how these inequities get reproduced.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, something we have talked about in the past and will continue to talk about in the future. I want to thank both of you for taking time to be with us today.

NORA KENWORTHY: Thanks so much for having us.

MARK IGRA: Thanks.

IRA FLATOW: Nora Kenworthy, Associate Professor of Nursing and Health Studies, Global Health and Anthropology at the University of Washington based in Bothell Washington, and Mark Igra, a graduate student in the Department of Sociology at the University of Washington in Seattle.

Copyright © 2022 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Shoshannah Buxbaum is a producer for Science Friday. She’s particularly drawn to stories about health, psychology, and the environment. She’s a proud New Jersey native and will happily share her opinions on why the state is deserving of a little more love.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.