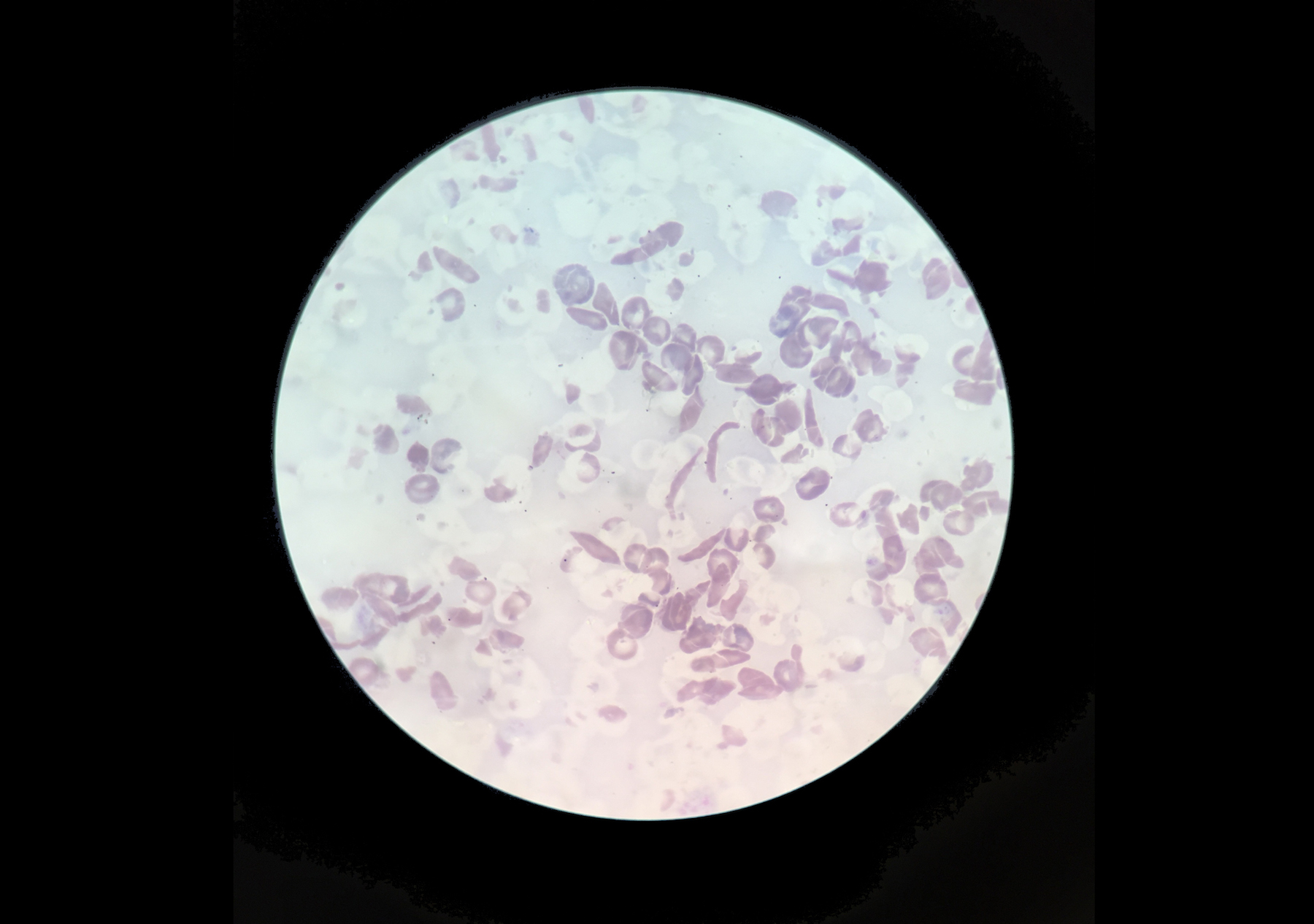

An FDA committee cleared the way for a revolutionary cure for sickle cell disease this week. If given final approval, the treatment would be the first to use CRISPR gene editing in humans. Sickle cell disease is caused by a genetic mutation that causes blood cells to develop into crescent or “sickle” shapes. The extremely painful and often deadly disease disproportionately affects Black and African American people.

Ira talks with Vox staff writer Umair Irfan about the new sickle cell treatment and other top science news of the week, including the link between the auto worker strike and a clean energy transition; new evidence about the moon’s origin; and why starfish don’t have arms.

Segment Guests

Umair Irfan is a senior correspondent at Vox, based in Washington, D.C.

Segment Transcript

This is Science Friday. I’m Flora Lichtman.

A bit later in the hour, we’ll talk about how the placenta can explain pregnancy loss and how nature’s deadliest poisons shaped the tree of life and us.

But first, RSV. It’s a common virus, but can be dangerous, especially for infants. So many parents breathed a sigh of relief back in July when an RSV shot for infants was approved. But here we are with RSV season upon us and many babies still haven’t gotten it in part because the shot is hard to find. Demand has outpaced supply. And this week, the CDC issued an alert about the drug’s limited availability.

Here to tell us about this and other science news from the week is my guest Katherine Wu, staff writer for The Atlantic, based in Boston, Massachusetts.

Welcome back to Science Friday.

KATHERINE WU: Always good to be here.

FLORA LICHTMAN: OK. So tell me about this RSV shot for infants. And I guess, first of all, I’ve heard some hedging around the language for what this shot is. Is it technically a vaccine?

KATHERINE WU: Great question. Love this question. It is technically not a vaccine– not in the traditional sense. It is a monoclonal antibody shot. We got used to this idea during the height of the COVID pandemic. But basically, this is another way to deliver protective antibodies to your body, except they are not made in house as a vaccine would do. So I wouldn’t call this a vaccine, but totally fair to call it a shot.

FLORA LICHTMAN: What kind of rationing is the CDC recommending for it?

KATHERINE WU: So this is basically a prioritization recommendation. The CDC is saying that because supply is low, the infants at highest risk should be prioritized for this shot, which is called Beyfortus. And basically that means infants under the age of six months, or older infants who have health conditions that would predispose them to a very severe case of RSV. The CDC is also saying that infants who are American Indian or Alaskan Native should still be prioritized for the shot because rates of RSV are especially high in those communities.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Why is the supply so limited?

KATHERINE WU: It frankly seems like the typical market situation, where demand was just not anticipated. Essentially, Sanofi, which is one of the companies that is behind Beyfortus, is saying they didn’t really see it coming. And they’re currently ramping up production. But given what you just said– RSV season is already upon us– it’s unclear whether they will be able to meet demand anytime soon.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Let’s move on to another big story from the week forecasters said that Hurricane Otis would be a Category 1 before it made landfall in Mexico. And then it intensified way past what people predicted. What happened there?

KATHERINE WU: Another great question. The big issue here is, as you just alluded to, a serious miss by forecasters. And it is absolutely insane how quickly Otis intensified. Within about 24 hours, it went from a tropical storm all the way to a Category 5.

I mean, that is kind of the hurricane equivalent of striking a match in your kitchen and seconds later seeing your entire neighborhood on fire. There was just no way I think forecasters were really able to predict that sort of intensification on such a short time span.

For more perspective, this hurricane gathered more than 100 miles per hour of wind speed within just 24 hours. And so, of course, when forecasters were looking just a day out, they weren’t that worried. And so when Otis made landfall, it was absolutely devastating. It wasn’t just that the prediction had been miscalibrated, but locals had no time to prepare or evacuate.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Is this an example of the storm just being a total fluke and strange, or is this an indication that the forecasting system really doesn’t work or needs some tweaks?

KATHERINE WU: Well, maybe a little bit of both. This is certainly a rare occasion. This kind of intensification absolutely is not typical. But it might be getting more typical. The current understanding is that the intensification happened, in part, because the oceans have just been so warm this year. Remember that heat is energy. And that is energy that a hurricane can feed off of. It’s basically drawing heat from the ocean to fuel its own winds.

And so the more heat is packed into an ocean, the more fodder there is going to be for a hurricane like this. And if oceans are expected to be warmer in future years, as climate change suggests they certainly will, that probably means a lot more intensification of this magnitude is in our future.

At the same time, it definitely would help to have more monitoring. But when things are this unpredictable, it’s hard to completely solve for that problem.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Let’s move on to a story you reported for The Atlantic. It’s about your complicated relationship with happy hour.

KATHERINE WU: That is a great way of putting it. So I will out myself here. I am not at all a habitual drinker. Whenever I do imbibe alcohol, my face goes insanely red. I get really flushed. I look like I’m just either very embarrassed or about to make myself sick. There is no way for me to drink without advertising it to the entire world.

I am one of the 500 million people around the world who experiences what’s called either “Asian glow” or “alcohol flush.” And there’s always been this huge question, why are there so many of us? It is no fun for us to drink. And we have a bunch of other health risks.

We are at higher risk of esophageal cancer and heart disease and a bunch of other things. This is just not a great genetic mutation to have.

FLORA LICHTMAN: So it’s a genetic mutation that causes it?

KATHERINE WU: Right. So basically, we don’t produce functional copies of an enzyme called aldehyde dehydrogenase. And this is necessary to break down the toxic components of alcohol. Without it, alcohol basically allows poison to build up a ton in our bodies, causing all of these side effects when we drink. And then, of course, the health risks because aldehydes can also appear in our body just through normal metabolism.

FLORA LICHTMAN: What was the new finding this week?

KATHERINE WU: Right. So maybe there is actually an explanation for why this genetic mutation is so prevalent. And the possibility here is that infectious disease may be to blame. Maybe when infectious diseases were even more prevalent than they are today and plagues were wiping out populations around the world, having this mutation was actually protective.

It’s actually not that big of a logical leap. Remember that this mutation allows poison to build up in the body. That’s certainly potentially bad for our cells, but it could be pretty harmful to any microbe that’s trying to invade us as well. And so scientists now know that these aldehydes that build up in the body can actually be quite harmful to bacteria such as tuberculosis.

FLORA LICHTMAN: So if you don’t break them down, maybe these aldehydes that are in the body can do some of this antimicrobial work for you?

KATHERINE WU: Right. So basically, it’s this idea of leveraging poison that already happens to be hanging around in the body, and leveraging it for self defense.

And I should quickly caveat here that this is not an endorsement of drinking to cure your diseases. It’s actually just the idea that having the mutation at all could be beneficial.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Let’s go to our next story. It’s about tiny furry mummies. Tell me more.

KATHERINE WU: Yes. So let me take you to one of the highest, most extreme environments on planet Earth. So high up in the Andes Mountains, it is a very, very, very harsh place to survive. It’s tens of thousands of feet above sea level. The temperatures are always freezing. It’s super dry. And the oxygen content in the air is about half what it is at sea level.

It’s just not anywhere that I would want to be for a long period of time. And frankly, I would probably die if I tried to do that without a lot of equipment with me. But the reason that this place has become so interesting to scientists is because it’s actually a decent simulation of conditions on Mars. A super harsh environment, without much oxygen certainly sounds extraterrestrial to us.

And what is fascinating is now scientists have found, exactly as you said, some tiny furry mummies up there. These are dead bodies of leaf-eared mice, which is a possible indication that there are mammals happily living up there in this ultra harsh Mars-like environment.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Do the scientists have a sense of how these mice survived up there?

KATHERINE WU: That is the next big question. So all they have done so far is provide a decent bit of evidence that these mice aren’t just tourists or passersby or that maybe humans were dropping them off up there. They’re finding mice of all ages, multiple sexes. It seems that they actually can happily live up there.

But they don’t yet know how. Just finding evidence that it’s possible, though, really opens up a bunch of questions. If we’re able to figure out how the mice are managing this, it could help us better understand how to colonize other planets potentially, and just maybe opens up new questions about what has been in Mars’s past– what might have survived up there, what sort of life has eked out a living.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Let’s go to our last story. New research suggests that wild chimpanzees go through menopause just like us. Why is this news? Is this unusual?

KATHERINE WU: This is definitely weird. And let’s take a step back and just think about how weird menopause is– at least from an evolutionary perspective. I mean, it does seem like a little bit of a waste, in a sense. Why not stay fertile for your entire lifetime? Why give up your fertility early? Or flip that question around– what is keeping animals alive past their prime reproductive years?

It can be super important for cultural things for humans, but technically it’s not adding on to future generations. And so this has been a huge pressing question for scientists for a very long time. And humans are very clearly so the only mammals that do undergo menopause.

For us, there were some ideas about maybe this is important for humans in particular. Our babies have these big brains. They’re so vulnerable for such a long time. Maybe it’s useful to have older generations around to care for these infants, keep teaching them, provide whatever extra supplementary care they can– this whole idea of, it takes a village, and grandmothers are awesome.

But the weird thing is, now that scientists have found potentially several other mammals, including these chimpanzees that seem to undergo menopause as well, that theory might be breaking down.

Chimps are, of course, our closest primate relatives. And if they’re undergoing menopause, that suggests, well, what if we had a common ancestor that was undergoing this? And what if it’s not because of giant brains and needing grandmothers around? Could it be something else?

FLORA LICHTMAN: What could it be?

KATHERINE WU: So that is the next question. This is another case in which they have documented the phenomenon. But the big question of why is still unanswered.

What’s really intriguing is scientists are now possibly looking to some evidence in whales to answer the why question with chimpanzees. So there are a few species of whales that also undergo menopause. But for them, it doesn’t seem to be necessarily a benefit of having grandmothers around to raise their children. And I actually love this other reason because it is just about the benefits of having older individuals around.

Older females aren’t just useful because they can contribute to the raising of children. Women are more than their childbearing capacity, in other words. Maybe these older individuals are around because they just help their species survive. They have more life experience. They can teach others around them to just be better at being chimps or whales or humans.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Yes, that is the kind of older woman I want to be.

KATHERINE WU: The same.

FLORA LICHTMAN: That’s all the time we have for now. I’d like to thank my guest, Katherine Wu, staff writer for The Atlantic, based in Boston, Massachusetts Thank you for joining us.

KATHERINE WU: Thanks so much for having me.

Copyright © 2023 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Meet the Producers and Host

About Shoshannah Buxbaum

Shoshannah Buxbaum is a producer for Science Friday. She’s particularly drawn to stories about health, psychology, and the environment. She’s a proud New Jersey native and will happily share her opinions on why the state is deserving of a little more love.

About Ira Flatow

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.