NYC’s Trees: A Natural Defense Against Heat, But Not Equally Shared

16:48 minutes

This segment is part of The State of Science, a series featuring science stories from across the United States. This story by John Upton (Climate Central) and Clarisa Diaz (for Science Friday).

This segment is part of The State of Science, a series featuring science stories from across the United States. This story by John Upton (Climate Central) and Clarisa Diaz (for Science Friday).

Taina was sitting with a friend in the shade cast by a large tree in Prospect Park in Brooklyn, NY on a Saturday afternoon in late July. Throughout the city, it was another scorching day for a population that had endured one of the world’s deadliest COVID outbreaks just months earlier.

“The heat is way too unbearable to be doing anything else but sitting in the park in the shade and kind of just enjoying that fresh breeze and that shadow,” said Taina, who asked Science Friday to use only her first name. “I live in Bushwick, and it takes me a while to get all the way across Brooklyn.”

As pollution traps heat and pushes temperatures upward around the world, residents of its cities are experiencing the sharpest changes, with forests and other cooling landscapes replaced by pavement and other hard surfaces that absorb heat. But the heat is being felt unevenly, with the legacy of redlining and urban development keeping wealthier and whiter neighborhoods cooler than poorer and browner ones.

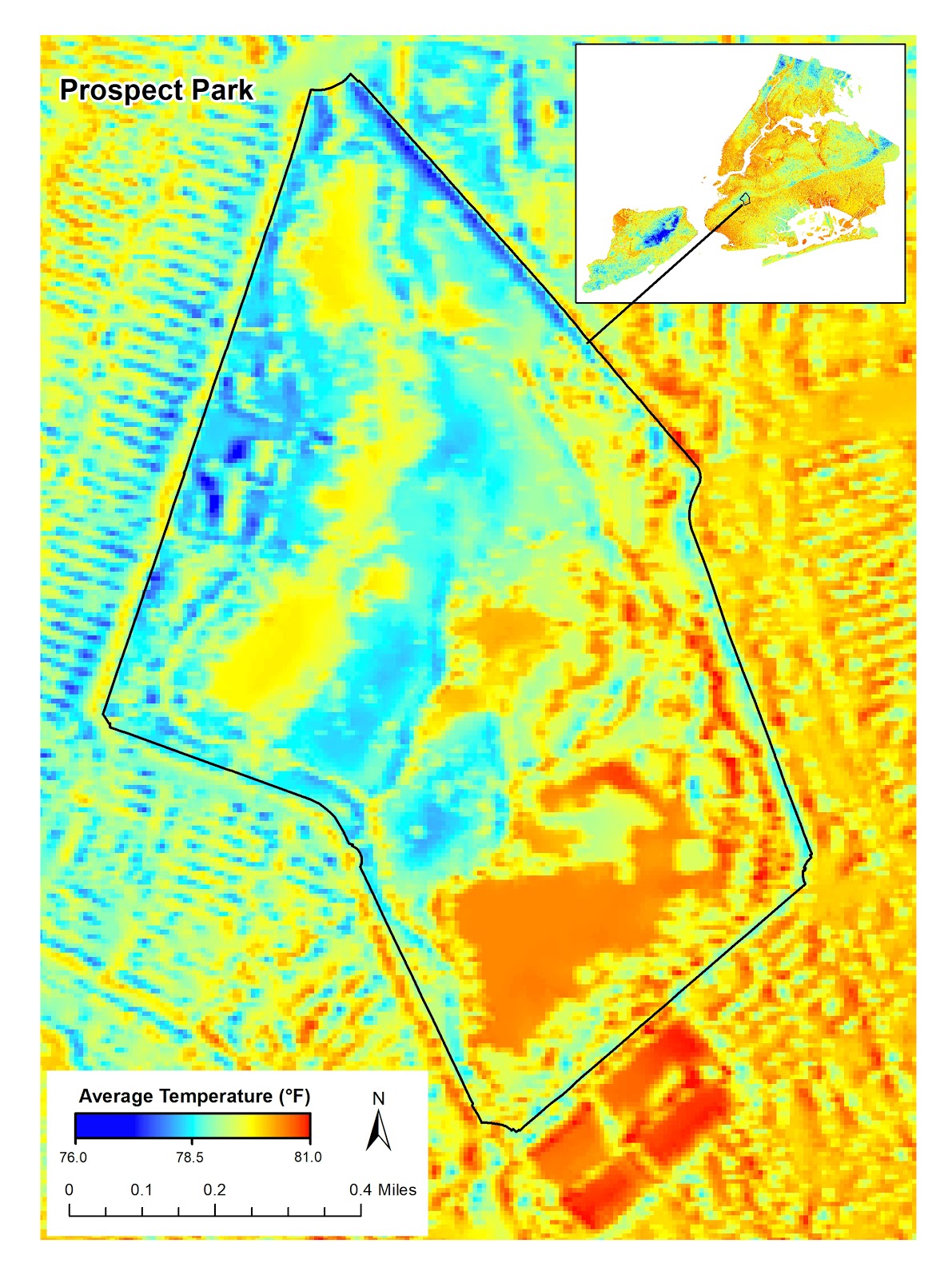

Luis Ortiz, a researcher at the New School’s Urban Systems Lab, used data obtained by a satellite passing over New York City several days before Science Friday spoke with Taina. It showed Bushwick, which is a working class industrial area on Brooklyn’s outskirts, in some places was more than 20°F warmer than Prospect Park and the tree-lined neighborhoods that surround it. The park is a nearly 600-acre behemoth of green space surrounded by a mixture of neighborhoods including the heavily gentrified Park Slope, where incomes and property prices are high.

Preliminary findings from survey-based research involving some of Ortiz’s Urban Systems Lab colleagues indicate that park visitorship jumped this summer in New York City compared with before COVID triggered shutdowns. But not everybody could find luxuriant respite. The researchers also found that many New Yorkers didn’t feel they could travel safely to a park during a pandemic, perhaps because parks near their homes are run-down or nonexistent and reaching larger ones require multiple bus trips.

The U.S. Forest Service estimates that New York City is home to 7 million trees overall. Such trees help counter the urban heat island effect, in which cities are warming more rapidly than surrounding countryside.

“We live in a pre-war building and it kind of traps the heat in during the summer months,” Will, a seven-year resident of Brooklyn, told Science Friday as he worked on his laptop beneath a tree in Prospect Park. “If we can get out here, even when it’s hot, it feels nice to be out in the breeze and near the trees and in the shade and everything.”

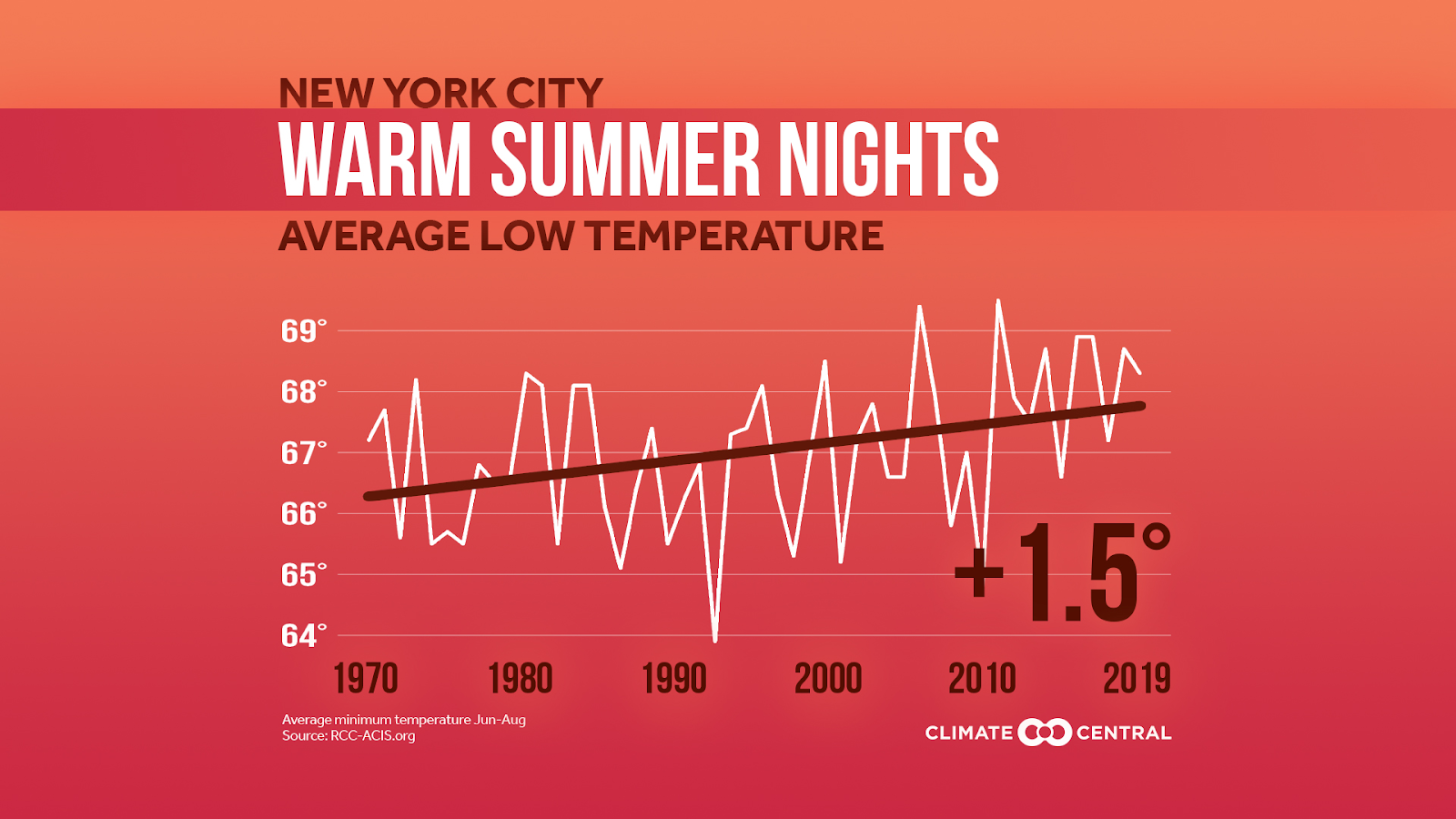

Average nighttime temperatures are rising more quickly than those during the day, making it harder for people to cool off at night and recover. And a slew of scientific papers published this year have been confirming that low-income neighborhoods throughout the U.S. lack tree canopy cover and are consistently hotter than those that house wealthier neighbors nearby.

“As the day heats up, the buildings and the sidewalks absorb heat and store it,” said David Nowak, a senior scientist at the U.S. Forest Service. In vegetated areas, by contrast, “trees are evaporating water and cooling the environment.”

Heat is America’s deadliest weather hazard, killing an estimated 12,000 every year. Seniors and those who can’t afford air conditioning are among those most at risk. Hot nights can be particularly insidious, because they rob people of sleep and deprive their bodies the opportunity to recover from heat experienced the previous day.

This year, large parks have provided neighbors with an opportunity to escape the heat while observing social distancing guidelines, while smaller parks can hold fewer visitors and are more likely to cram those who do visit together.

“The heat island effect tends to be greatest just after sunset when the sun goes down,” Nowak said. “The rural surface and natural surfaces tend to cool out faster than the urban surfaces. So you get the rural area cool off quicker than the urban area.”

After Nowak led efforts to model summertime air temperatures across the city more than a decade ago, clear differences could be seen following the contours of its parks, water bodies and other green spaces.

“You can see these pockets of cooler surface air temperatures across New York City,” Nowak said. “You get a huge cool island effect in the center of Staten Island. But also you can see pockets of cool around some of the bay areas. Also in Prospect Park, some other park areas such as Central Park, the surface temperatures tend to be cooler.”

It’s common for neighborhoods to be sharply divided in terms of the tree cover they contain, with those home to those with the lowest incomes faring the worst. These neighborhoods contain fewer trees and tend to be denser, allowing less air circulation. The problem is not unique to the U.S.—”This is a global phenomenon,” said Chandana Mitra, an associate professor at Auburn University in Alabama who has studied such patterns around the world.

U.S. Forest Service research forester Morgan Grove helped pioneer research into the distribution of canopy cover and heat in Baltimore. He worked on a study published this year comparing tree cover in neighborhoods that were “redlined” a century ago by federal policies, depriving mortgages and curtailing investments from areas home to Blacks and immigrant communities.

The study examined 37 cities and Grove said wealthier neighborhoods had more than twice the amount of canopy cover than did the formerly redlined areas. “That was true regardless of the age of the cities, or in terms of the climate where the cities were throughout the United States,” he said.

Reshaping an urban environment to usher in more greenery can be a challenging endeavor. With New York City built out and up over hundred of years into a remarkable metropolis, there aren’t many places left here where big new parks could be plonked down. The good news? Grove and other experts said small clusters of trees spread out through a city offer advantages over large parks when it comes to cooling as many residents as possible.

In ongoing research that has been presented publicly by Grove’s research partners but not peer reviewed or published, cooling benefits for surrounding neighborhoods were found to increase with the size of a park until it reached roughly the size of a football field, then the increase in benefits tapered off.

“To translate it, it’s better to have lots of small air conditioners throughout the city than big air conditioners,” Grove said.

The finding didn’t surprise other experts interviewed for this story. It suggests abandoned or redeveloped land wield vast potential to help New Yorkers adapt to climate change by helping cool down their neighborhoods. Retrofitting cities with more pocket parks and trees comes with substantial added maintenance costs in addition to up-front capital costs.

“We have not come to terms with the real cost of what solutions for building resilience to climate change look like,” said Timon McPhearson, director of the Urban Systems Lab at the New School in New York City. “The fact that nature is going to cost money to invest in should not be surprising to us.”

Individual trees in cities can cost thousands of dollars to purchase, plant and establish. A tree growing in a dense part of a city is harder and more expensive to keep alive than one growing in a forest within a sprawling park. Street trees can be particularly difficult to keep alive.

“One of the most important things we can do is to plant trees to transform vacant lots into vegetated and small pocket parks, to take basically the availability of any space that’s either being redesigned or reimagined or is still available, and make those spaces green,” McPhearson said. “This is critical for climate resilience in low-income and minority neighborhoods.”

One of the richest cities in the world, New York City is home to initiatives to increase tree cover in neighborhoods where it presently is sparse and expand parkland. Since 2007, its parks department says it has planted more than 500,000 native trees and shrubs where canopies had been lost, damaged or jeopardized by age. New trees are being planted where they can shade seating and walking areas.

Still, the inequity in tree coverage is a stubborn one, locked in place by urban planners of the past. And amid the pandemic, trees and parks are falling victim to municipal cost-cutting, even as fiercening summers and social distancing rules highlight their importance. New York City’s parks department’s budget this fiscal year was set at $503 million—$84 million down from last year, preventing it from hiring seasonal maintenance and operations staff.

A lack of tree coverage in a neighborhood jeopardizes more than physical wellbeing. It also contributes to stress and anxiety. “There is a booming body of literature on the benefits of green space exposure for both physical and mental health,” said Alessandro Rigolon, an assistant professor in the University of Utah’s city planning department.

Yet the intended beneficiaries of new and improved parks can end up becoming their victims, leading to gentrification that displaces longtime residents from an area as it improves.

Rigolon said larger parks and open space projects, such as the revitalization of the Los Angeles River, tend to have particularly strong effects on gentrification. So, too, do parks built close to downtowns and linear parks like the Highline that can connect cyclists and pedestrians with different parts of a city. “We don’t know about the gentrifying effects of pocket parks yet,” he said.

Because of these gentrifying impacts from parks, Rigolon said that “when we do invest in those amenities,” it’s important to be “upfront in our efforts to do something about affordable housing, both in terms of maintaining existing affordable housing and building new.”

Rigolon said the disparity between rich and poor areas can be even greater when talking about the number of trees than the number of acres of parkland, partly a legacy of nonprofit and volunteer groups prioritizing street tree plantings and maintenance in wealthier and whiter neighborhoods.

“Environmental nonprofits were mostly helping those more affluent communities, because that’s where the early environmentalists started from,” Rigolon said. “The momentum movement is fortunately evolving, and it’s evolved probably in the last 20 years to recognize issues of justice and equity.”

To maximize the likelihood that trees planted in neighborhoods can survive and provide cooling and other benefits for years and decades ahead, Rigolon said neighbors should be involved in decision-making alongside environmental nonprofits that are thoughtful about issues of equity.

“If it’s top down from the city, it’s harder to get buy-in from those communities,” Rigolon said. “There’s a distrust for public institutions among communities that have been the object of systematic racism for generations.”

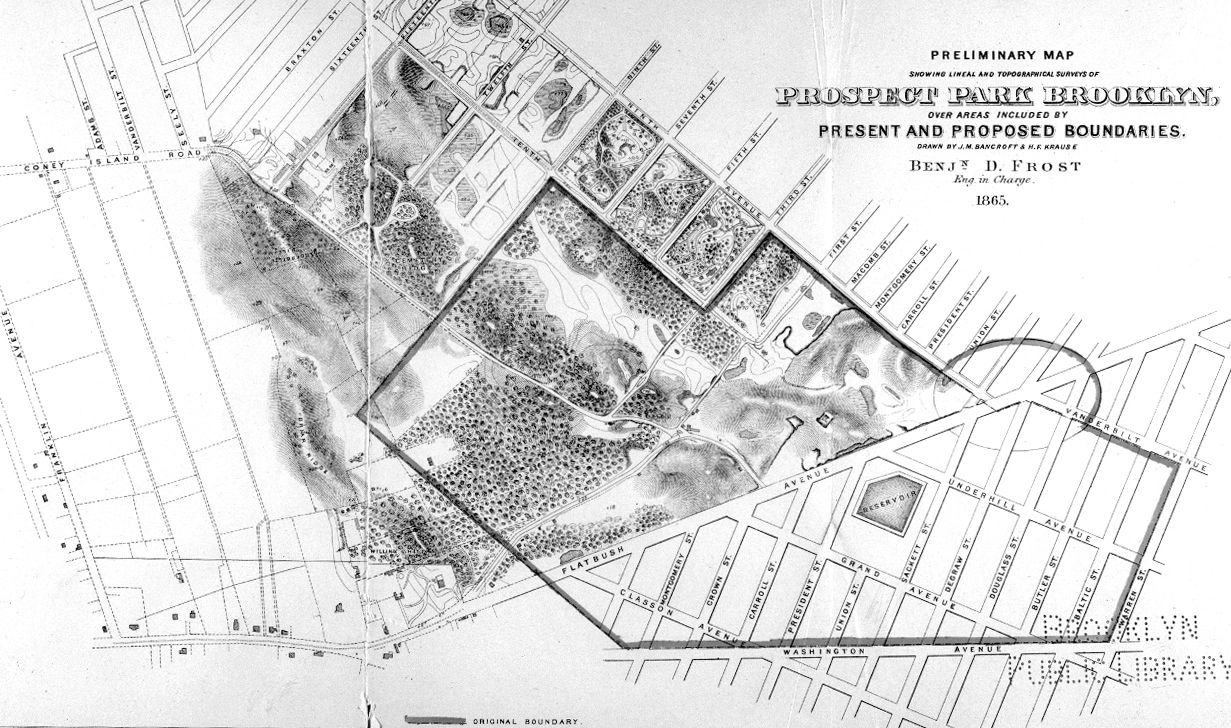

The Prospect Park Alliance, a nonprofit group that normally operates with an annual budget of $11 million (its estimated shortfall this year amid the pandemic is $3 million) has been improving the nearly 600-acre urban treasure since 1980s, following a decline in public spending that began during an economic crisis in the 1970s.

“There was a lot of decline and neglect that happened in the city parks,” said alliance spokeswoman Deborah Kirschner. “The budget levels never went back to whatever they had been previously, and a lot of the big parks in the city do have private nonprofits that help raise funds and employ staff and provide resources.”

The alliance employs park workers and landscape architects, helps maintain the park’s natural areas, works on forest restoration projects and runs volunteer and education programs, enriching the neighborhood with a sweeping escape from its hot and congested buildings and streets.

“I think everyone deserves access to a park and access to have that moment of peace and tranquility away from the city, the noise, the hustle and bustle, and just being around green,” said Liz, who was enjoying a picnic under a tree in Prospect Park on the hot summer day. “It’s like a natural antidepressant.”

This story and radio segment were produced through a partnership between Science Friday and Climate Central, a nonadvocacy science and news group, with support from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Clarisa Diaz is a reporter and designer at WNYC in New York, New York.

David Nowak is a senior scientist and i-Tree Team Leader with the Forest Service in Syracuse, New York.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. It’s time to check in on the state of science.

SPEAKER 2: This is KERN.

For WWNO.

St. Louis Public Radio–

Iowa Public Radio News.

IRA FLATOW: Local science stories of national significance. New York city’s skyline is dominated by tall skyscrapers. But even though the city is known as a concrete jungle, there is a forest among that jungle. Tree canopy covers about 20% of the city. And woodlands are one of the few natural resources this city has.

Clarissa Diaz reports how New York City is using green space, large and small, to create an urban forest ecosystem in the face of climate change.

CLARISSA DIAZ: In the heart of the Prospect Park Woodlands, the coolness of the breeze is a relief from the heat on a summer’s day. But it’s not just any summer, it’s a pandemic summer.

SPEAKER 4: I feel like Prospect Park is usually packed. But I have seen an influx of groups of people here for sure more since COVID.

CLARISSA DIAZ: Tyena and her friend Cherise have come to the park almost every weekend since the summer began. And for Tienna, it’s quite a trek.

SPEAKER 4: I live in Bushwick, and it takes me a while to get all the way across Brooklyn. We don’t have nature like this around the city. So you need a place that feels local. That feels accessible that you can come to.

CLARISSA DIAZ: For New York City residents cooped up in their apartments during the middle of summer, it’s literal cabin fever.

SPEAKER 5: We live in a pre-war building, and it traps the heat in during the summer months. You can find a space that can call your own, or at least just escape.

SPEAKER 6: It’s cooler than hanging out by the concrete area.

SPEAKER 7: Concrete retains a lot of heat.

CLARISSA DIAZ: On average, urban forests in the city are about five degrees cooler than their surrounding areas according to the US forest service.

DAVID NOWAK: The average tree cover is around 21% across the whole city. And the city contains, from field samples, we estimate about seven million trees.

CLARISSA DIAZ: That’s David Nowak, senior scientist and iTree Team Leader at the US Forest Service. His team has developed an air temperature model, which looks at the weather conditions of New York every hour along with the surface parameters around each site of trees in the city.

DAVID NOWAK: As you move more towards impervious service and less away from trees and natural systems, you tend to get this greater heat island effect.

CLARISSA DIAZ: The urban heat island effect makes swaths of the city with fewer trees hotter in the summer as temperatures. Become more extreme, residents that do not have adequate means of cooling down may become more vulnerable.

DAVID NOWAK: I mean, the cities are hundreds of years old. And they have this infrastructure and this history of being built. They are what they are. It’s pretty probably easier to design parks as you develop a city in the beginning than try to retrofit parks in afterwards. Not that it can’t be done, but there are a lot of problems in doing that.

CLARISSA DIAZ: According to Nowak and other scientists, while more cooling can be achieved around a specific site with a grouping of trees, the spreading out of trees could lower temperatures across the city. Though not as cool as a large park would, but could provide some relief where city dwellers live.

DAVID NOWAK: You have two types of things going on creating these respites of cool air temperatures in the parks people can go to. But also, if you don’t have access to those parks, you want to create cooler air temperatures in and around the spaces where people are living, and individual trees can do that.

CLARISSA DIAZ: One key to making sure trees can thrive in urban environments is maintenance. Street trees, for example, need to be insured enough space for their roots to grow in proper soil conditions. The conditions for growing urban trees are specific to the site and the type of tree being planted.

DAVID NOWAK: You’ve got to look at it from the forest perspective and not necessarily the single tree perspective that you could have many trees of different sizes throughout an area that can create these cooler pockets. Like in a forested stand, we have all sorts of tree sizes that create that cooling environment.

CLARISSA DIAZ: The idea of planting a single tree in a larger system for reforesting the city through time makes the forest perspective unique from typical urban street landscaping, which may only take into account a particular neighborhood or site. What if tree plantings could be planned so that the cooling effects in adjoining neighborhoods could be combined? John Jordan is the director of landscape management at Prospect Park Alliance.

JOHN JORDAN: We’re really one of the first parks in the city that started doing organized forest management. And the Prospect Park Alliance, even at its outset, was really oriented all around saving the forest and forest restoration.

CLARISSA DIAZ: Jordan takes us on a tour of the park’s restoration efforts starting at the edge of the parks 526 acres.

JOHN JORDAN: Those are what we call perimeter woodlands. They’re impacted in a really different way. They have more invasive species, more human impacts, things like that.

CLARISSA DIAZ: They kind of serve as a buffer.

JOHN JORDAN: They serve as a buffer. And from a cooling perspective, they’re super important.

CLARISSA DIAZ: As we walk along the perimeter of the park, there’s more and more shrubbery.

JOHN JORDAN: Once you get a little further, you’ll see there’s a fence and a bunch of green behind those trees. And that’s going to be here the start of our reforestation or aforest station project where, basically, we took a trees and turf area that was having a lot of negative human impacts, and we’re starting to try to convert that back to an actual woodland.

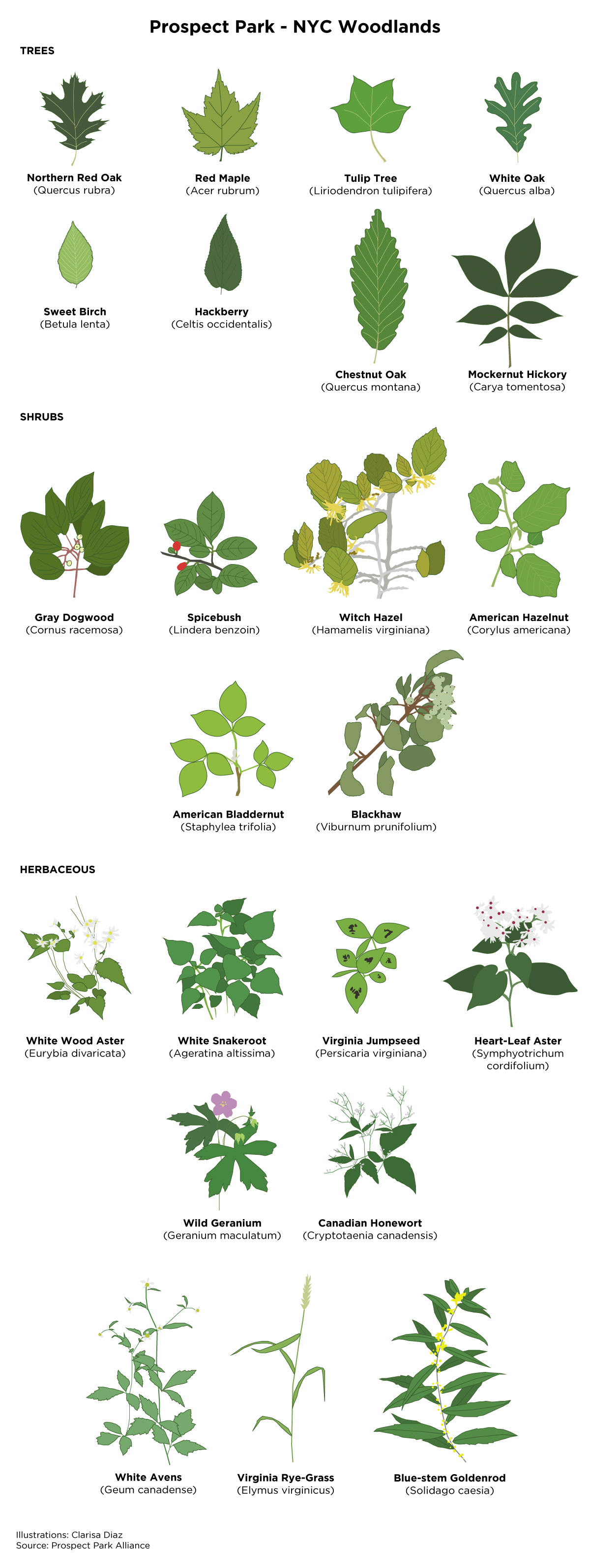

CLARISSA DIAZ: The landscape gradually turns into a more mature urban forest showing distinct growth from one to four years of planting and maintaining trees. Those tulip trees are really doing well. They’re filling in the space. Now, we’re looking at several years of growth of a really fast growing tree. This is meant to be kind of like a meadow planting that would fill in and become forest over time.

CLARISSA DIAZ: Balancing the plantings of slow growing trees and fast growing trees is a delicate craft. Take the oak tree.

JOHN JORDAN: They’re more like long term strata. They’re going to grow slower, but they’re going to live longer. So the tulips probably will die 100 years. Maybe one of these tulips will fall down or get blown over. And the oak will take that opportunity to push up through the next layer.

CLARISSA DIAZ: But as temperatures warm and New York City’s climate zone shifts, some native trees, such as the sugar maple, are becoming more sparse. Species from the south are creeping in. And native trees that have a large range may become more dominant.

JOHN JORDAN: For example, tulip tree that we were looking at earlier grows all the way down to– through North Carolina, South Carolina, and beyond. And also, species like red maple or sweet gum, both native trees of ours, there’s red maple in Florida. And sweet gum grows all the way down to central Mexico.

Species like that will probably play a bigger role. The species that we know aren’t at the end of their range here.

CLARISSA DIAZ: And as for the sugar maple?

JOHN JORDAN: Essentially, we’re still planting them, but not as much as we used to because, I think, we’re a little worried about their longevity.

CLARISSA DIAZ: In an average planting season, Jordan estimates the Alliance plants 300 to 1,000 trees in the woodlands with another 500 to 2,000 shrubs.

JOHN JORDAN: We think that this area was forested pretty much since the park was created, maybe even before. The bigger trees have been here the whole time. What’s really different is the understory.

CLARISSA DIAZ: The Prospect Park Alliance works tirelessly to continue the growth of the woodlands that, in parts, has existed longer than the city itself. For Science Friday, I’m Clarissa Diaz.

IRA FLATOW: Clarissa Diaz is a reporter and designer at New York’s WNYC. She produced that story in partnership with John Upton at Climate Central and the Pulitzer Center on crisis reporting.

Now, we’re going to talk about the science behind planting an urban forest and how you figure out the benefit of a single tree. Let me introduce my guest. Dr. David Nowak, who you heard in that report, is a senior scientist and leader of the iTree Team with the Forest Service. We’ll talk about what that is a little bit later. He is based in Syracuse, New York. Welcome back to Science Friday.

DAVID NOWAK: Thanks, Ira. Glad to be here.

IRA FLATOW: In terms of trees, New York City is known for Central Park and other parks with lots of trees in one place. You talked about this in the piece. But the idea is thinking about a city in terms of an urban forest. Is this a new way of thinking, David?

DAVID NOWAK: It’s not necessarily new. Urban forestry, as a profession, has probably been around through the ’70s and ’80s starting in that time. But it’s becoming more and more popular now in that we have more and more data over the last 10 or 20 years. And we’re learning more about what these trees and our cities do.

IRA FLATOW: So it’s the idea of trying to get an additive effect of trees spread around a city.

DAVID NOWAK: Correct. There’s trees, not only in Central Park and where they’re concentrated and forest stands, but they’re spread out through backyards, along streets, throughout the whole city of New York and other cities. And these trees provide multiple benefits related to cooler air temperatures, removing air pollution, affecting water, affecting our human health as we view that.

So they have multiple benefits and there’s a high diversity of different types of species in different locations throughout cities.

IRA FLATOW: I think a few city dwellers think about their urban forest as having any other benefit besides a nice place to go eat lunch.

DAVID NOWAK: Well, that’s a common one. People appreciate various things. I think they appreciate that, the view, the aesthetics of the forest. I think they can understand cooler air temperatures because, naturally, as the city heats up, we tend to walk in the shade into cooler areas. So we can sense those.

But there’s many other benefits that people may not perceive such as the air being cleaned and water reductions going down, absorption of uv radiation, changes and sound. So just having these leaves out there, the biology of the– and the chemistry of the leaves and the physics of these elements of nature throughout the city affect our lives in many ways.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s talk about how you balance clustering versus spreading trees. Let’s say you have 100 trees. How would you plant them the best way in a city?

DAVID NOWAK: Well, that’s an excellent question. It would depend on, first of all, the space that you have. So to get a greater effect for area, it is best to cluster them if you have the space. So temperatures would probably drop more as you put those 100 trees together so we drop the cooling effect. But then, those 100 trees are limited to just that space that you planted in. So fewer people would probably receive that benefit, but the benefit would be greater at that local scale.

On the other side, if you spread those 100 trees out across the landscape, each individual tree will probably be a lesser impact per tree. But more people might receive those lesser impacts. So it’s a question of, if you have the space, clustering together is good for many reasons. But in many cases, we don’t have the space. So it doesn’t diminish the capacity of the forest to provide services, even if they’re spread apart.

IRA FLATOW: If you plant the trees together, do they sort of help each other out to grow?

DAVID NOWAK: Well, yes and no. In some ways, the services– because they’re planted together– will tend to get greater temperature reduction. But you also tend to block winds more with the greater conglomerations of trees. But on the other side, if you plant them together, they tend to grow slower because trees need light and water to grow. If you have trees in a forest stand, they’re all competing for that limited resource of light and water.

So we tend to have more competition and maybe more mortality, in some ways, in these forested stands. Because it’s hard for a small tree– a seedling that’s established in a forest stand to make it to maturity because it has to compete with not only animals that might eat it, but all the light and water that it needs to grow.

Where singular trees in cities have less competition for light and water. Often people water them. So in some ways, they’re better off and may be healthier– in some cases– being in open growing situations. But often, we put them in narrow pits near roadways, which limits rooting space, which cause problems. There can be vandalism, damage to the trees, pollution. So the other factors that could diminish the health.

There are benefits of having trees together. But there also tends to be a competitive factor of having that forest stand by the trees next to.

IRA FLATOW: I know anybody who goes into a stand of trees knows there’s a cooling benefit that comes with the trees. And it’s more than just shade, right?

DAVID NOWAK: Yeah, it’s definitely more than just shade. There’s a lot of evaporative cooling. So the trees are basically pumping water from the soil then evaporating at the leaf surfaces. And evaporation is a cooling process. You’re feeling two things when you go into the interior stands or stand in the shade of a tree. You’re getting less radiation hitting you. So you’re not heating up as much.

But also, you’re getting that evaporative cooling that’s blowing from the leaves down to you. So you’re getting cooler air temperatures refreshing you as the air passes over you.

IRA FLATOW: So if you took out all the trees in a city or a space, you would radically change the urban feeling there.

DAVID NOWAK: In so many ways you would. Visually, definitely, you would see the change. And that would have a big impact, I think, on people. But the physical environment would change. Temperatures would go up. Wind speeds would go up. It would become– sorry, they would become warmer.

But there’d be more pollution in the atmosphere because the plants are actually absorbing pollution. As it’s transpiring those gases through the leaf surfaces, it’s also taking in air pollution and the gases and removing it at the leaf surface. So many attributes of the environment would change. The acoustics of the environment would change.

There’s so many ways that– again, we maybe not appreciate all them, but once you– you’ll appreciate it once they’re gone.

IRA FLATOW: If you’re an urban planner or a tree specialist, like you are, how do you decide what tree would work best in what city?

DAVID NOWAK: Partly it’s based on local expertise of experience of knowing what trees will survive. But also, we’ve built a tool called iTree. We’re trying to help people match up the trees to not only surviving in their area, but what services they provide. When you plant a tree, you want the tree to survive. So you want the right tree in the right space.

So big trees do better than small trees. Long-lived trees do better than short-lived trees. You have to fit it to the space and the conditions of the soil in the environment around that. Like bigger trees produce more leaves. They’re better at removing air pollution. They’re better at reducing temperatures. Some store carbon better. So when you design your sites, look at what problems you might trying to solve. And then, pick from your palette for which trees do best on that.

We have a series of tools. They can use the tools and do it themselves. That’s the concept of iTree to build this data to let people easily collect data and make their own local assessments and their own local decisions. But in the process of doing this, we like working with the cities to learn what they need to do so we can customize these tools to meet their needs.

IRA FLATOW: So anyone can download this iTree app and figure out the value of their trees.

DAVID NOWAK: It’s for anybody. We try to make it as simple as possible. The myTree app is a single tree app that works on your phone where you can record where you’re at. You put the tree species and size, and it’ll tell you the value of that tree at that location. Very simple tools. We designed that for homeowners and kids. There’s a tool called Design where you can sketch your house and put trees around it. So it’s very site specific for a few trees.

If you start getting into a large number of trees, like the city of New York where we had the sample, anybody could do it. But it tends to be more people that are professionals and managers that want to know about larger systems.

IRA FLATOW: I’m Ira Flatow. This is Science Friday from WNYC studios. We’re talking about the urban forest with David Nowak, a senior scientist and leader of the iTree Team with the Forest Service.

When you say the value of a tree, what is the metric that you’re using to measure the value? In terms of what? What is the value?

DAVID NOWAK: From the structure of the forests locally, we try to assess what the tree does, the services provided. We’ll never know the true value because we’ll never be able to assess all of the true values, such as aesthetics is very difficult. What we focus on is pollution removal, changes in water flows and water quality, air temperatures, carbon storage, effects on building energy use.

And many of those we can quantify. Building energy use, if we quantify how many kilowatt hours are being saved due to the evaporative cooling and shading of buildings, we can use local utility costs to determine what the monetary value of that is.

For things like air pollution, we look at changes in pollution concentration and how many people in the area. Then, we use a program from EPA called BenMAP to look at metrics of how changes in concentration affect human health metrics, such as mortality, asthma, and other things– heart attacks. So we use various methods to try and get out how it affects people or their, say, energy use. And then, put a dollar value on those services.

IRA FLATOW: So you can actually measure how much money a tree saves for a city.

DAVID NOWAK: Yes and no. Saving energy is a direct saving. Saving health effects is indirect. The city doesn’t directly see that. But people will see that through better human health, lower cost to health care because they won’t have to go to the doctor as much.

Some are more direct that you can see out of your pocketbook. Some are more indirect savings. And again, they’re all conservative. So there are many things that we haven’t been able to quantify yet.

IRA FLATOW: Tell me what it’s like being a forestry person working in a city or working with cities. What would you want people to know about their urban forests?

DAVID NOWAK: I think working in cities is one of the best places to work because the trees have a direct impact on the lives because the trees are very local. Where in more rural forest stand, there are a lot of trees and very few people. In the urban forest, there are a lot of trees and a lot of people. So you have a direct interaction day to day with these trees. And many people love the trees and are attached to trees and just enjoy being in the forest or the attributes of the forest such as wildlife.

So it’s exciting to be in cities just because of the interaction with people and their environment around them.

IRA FLATOW: Terrific. Thank you very much for taking time to be with us today.

DAVID NOWAK: Thanks, Ira. Much appreciate it.

IRA FLATOW: Dr. David Nowak is a senior scientist and leader of the iTree Team with the Forest Service, and he is based in Syracuse, New York. Also thanks to reporter Clarissa Diaz for bringing us that story.

Copyright © 2020 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Alexa Lim was a senior producer for Science Friday. Her favorite stories involve space, sound, and strange animal discoveries.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.