Cosmic Questions In Comic Book Form

29:24 minutes

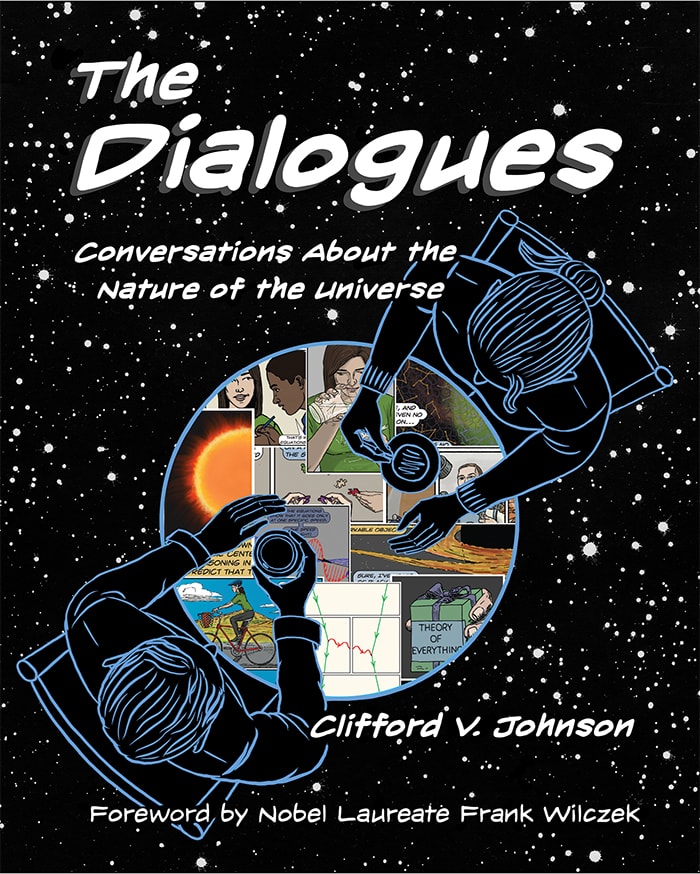

Comic book superheroes use and abuse physics for their supernatural powers. But how many can actually explain the physics behind gravitation or electromagnetism? In The Dialogues, the new graphic novel by physicist Clifford Johnson, the heroes are scientists—and though they have no special powers beyond their scientific abilities, the characters address everything from the mysteries of dark energy to the possibility of immortality.

Comic book superheroes use and abuse physics for their supernatural powers. But how many can actually explain the physics behind gravitation or electromagnetism? In The Dialogues, the new graphic novel by physicist Clifford Johnson, the heroes are scientists—and though they have no special powers beyond their scientific abilities, the characters address everything from the mysteries of dark energy to the possibility of immortality.

[What exactly *is* pancake ice?]

In this interview, black hole physicist Janna Levin joins Clifford Johnson to discuss the quantum questions vexing physicists today—and why black holes might be the perfect place to find the answers.

Clifford Johnson is author of The Dialogues: Conversations about the Nature of the Universe (2017, The MIT Press), a professor of Physics, and Co-Director of the Los Angeles Institute for the Humanities at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, California.

Janna Levin is author of Black Hole Blues and Other Songs from Outer Space (Knopf, 2016) and a physics and astronomy professor at Barnard College in New York, New York.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. A bit later in the hour, the soil is not what you think it is. This is going to be another mind-blower later. But we’ll get to that later. Let’s talk about a another mind-blower here. How much physics can you learn from a comic book?

If you’re talking about the plot points in a regular comic book, probably not much. But there’s a new graphic novel called The Dialogues– Conversations About the Nature of the Universe, where the stars of the comic strips are physicists, debating everything from electromagnetism and the meaning of a multiverse, to the singularities of black holes and the big bang.

This is not your average comic book. In fact, it spelled out for me, different things I had never– you know, were hard to visualize before. I could look at the comic book, watch and listen to the conversations going in there, sit back and think, oh, that’s why that is. It’s a gorgeous– Clifford V. Johnson is the author.

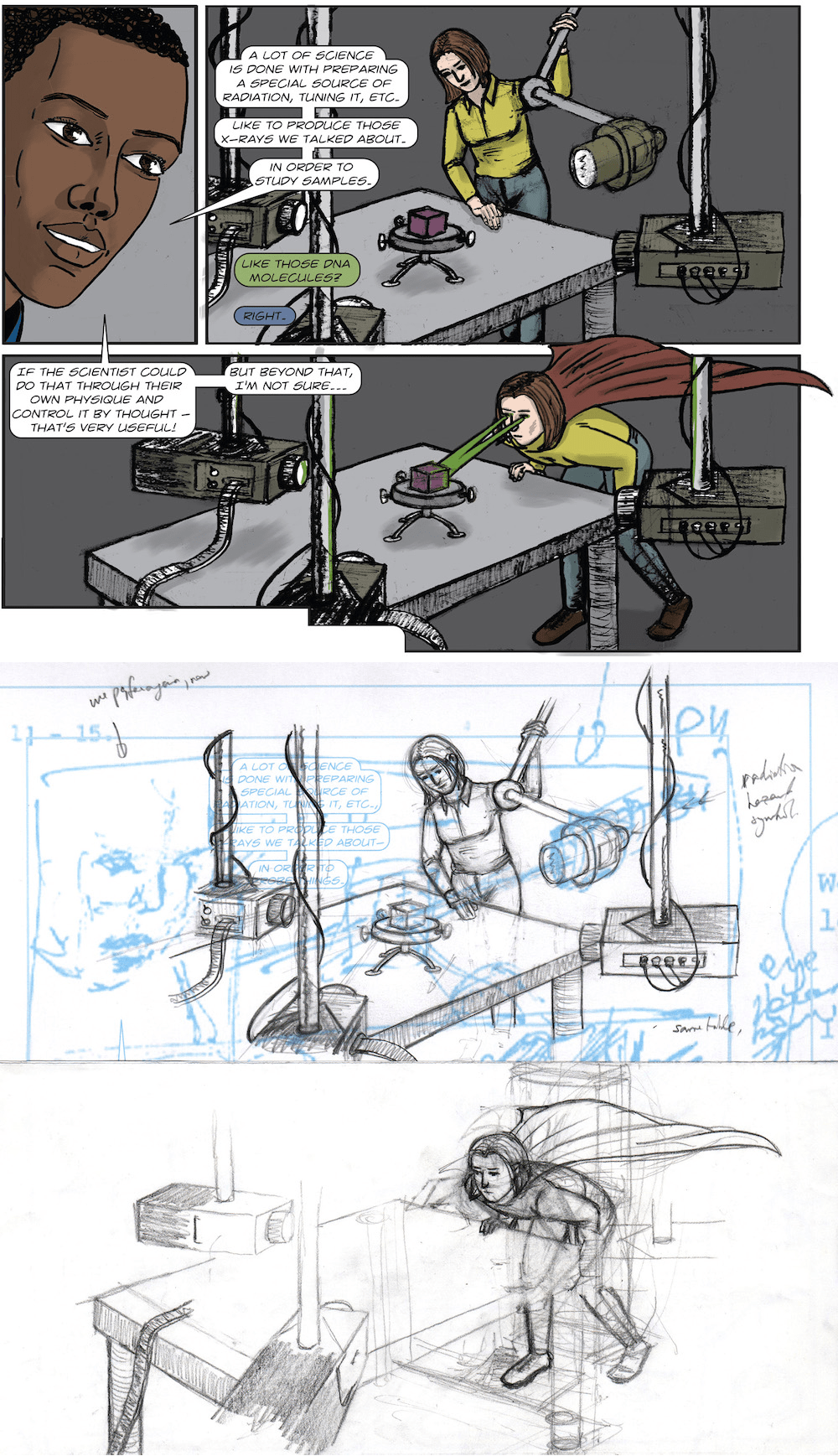

He’s a theoretical physicist himself and he taught himself to draw. That’s amazing. To create this beautiful book, and we have some of his original sketches for the Dialogues up at our website at sciencefriday.com/physics.

Clifford is also a professor of physics at the University of Southern California, co-director of the LA Institute for the Humanities there. Welcome to Science Friday, Dr. Johnson.

CLIFFORD JOHNSON: It’s a pleasure to be here.

IRA FLATOW: You’re a working physicist, but you taught yourself to draw, to make this book. It looks like the work of a comic industry veteran.

CLIFFORD JOHNSON: Oh, that’s very kind of you. Yes, I think it sort of fits with what we do as theoretical physicists, which is we’re interested in probing a particular research area– we need to learn some new techniques, so we just take the time-out and learn the techniques. So that’s what I did.

IRA FLATOW: It’s over 200 pages– all kinds of– must be 1,000 panels, or more, in there. How long did that take to do?

CLIFFORD JOHNSON: Well, bearing in mind I have my professor gig during the day, as it were, I was mostly doing this in my spare time, except for the last semester, where I had a sabbatical semester.

And so, I started drawing on it seriously in around 2010 was when I started trying to figure out whether I could draw for it.

And then, realized that it was possible. And then, over the years during spring break, and between bits of research and what have you, I did it until I finished in 2016.

IRA FLATOW: That’s just amazing. And that the book is called, The Dialogues. And the dialogue and the graphic novel aspects, I think, to me reading it, takes the scary part away from it. And I was trying to come up with an analogy for what the book is like to read, and I came up– I was watching the film of Henry V last night, on TV. It’s one of my favorite Shakespeare plays.

And if I were just to read any Shakespeare, it’s very hard to understand what’s going on in the scene, but if you graphic– make it into a film or video, and watch the actors, they sort of bring to life between the words. And that’s what I see you have done in your book.

Some of these concepts seem to be very scary, but when you create the graphics and the dialogue between the characters in there it loses that scary part, and you say, oh, that’s how that works.

CLIFFORD JOHNSON: Thank you. That’s what I intended and I’m really glad to hear that it works in that way. That’s a really great analogy with bringing the page– the words on the page to life in theater or film. That’s a great analogy. Thank you.

IRA FLATOW: Speaking of bringing to life, I want to bring on Jana Levin, who is author of Black Hole Rules– Blues, I’m sorry– Black Hole Blues, and has a new special on black holes out at NOVA, this week. She’s professor of physics and astronomy at Barnard College of Columbia University. Good to have you back.

JANNA LEVIN: Thanks. I’m here and I am alive.

[LAUGHTER]

It’s true. And it’s good to hear you, Clifford.

CLIFFORD JOHNSON: Hi. Great to hear you.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s talk about one of the ideas Cliffard plays within the book, is this perception in the media and the public, which is string theory– right or wrong? Multiverse– right or wrong? Which sides are you on, and so on. But, in real life physics, it’s not quite as black and white, is it Janna?

JANNA LEVIN: No, I think it’s really important as a scientist not to put a belief system first. The whole point is to explore the unknown. So you don’t want to walk into any field and say, this is what I believe. There has to be a certain agnosticism about everything.

And so, approaching string theory or the multiverse, you may have a strong intuition that it’s right or wrong, but it’s really important– and that might drive you to ask a particular question or pursue a particular calculation– but it’s really important to always be open-minded to the other point of view.

IRA FLATOW: And that’s what is one of the strengths of this book, Clifford, is that you have a dialogue. The book, the cartoons, the novel is based on two people sitting together over a cup of coffee or in a train, and they’re having a dialogue about something, questioning each other’s beliefs, asking them to give them their opinion, and sometimes not agreeing, but then trying to find some common ground of belief there.

CLIFFORD JOHNSON: Yeah. And I was trying to– I was trying really to celebrate that kind of conversation, which no disrespect to some of the wonderful science books that are out there, but it did seem that a lot of them sort of clean up the discussion in a way where you lose that conversational aspect and the messiness of conversation, which can be quite engaging.

So I try to represent that kind of conversation in the book, and really show the various kinds of issues that get people into heated debates.

And then tried also to show that it’s just by no means clear. Research doesn’t work in the very simple way that these sorts of which side are you on debates are often presented.

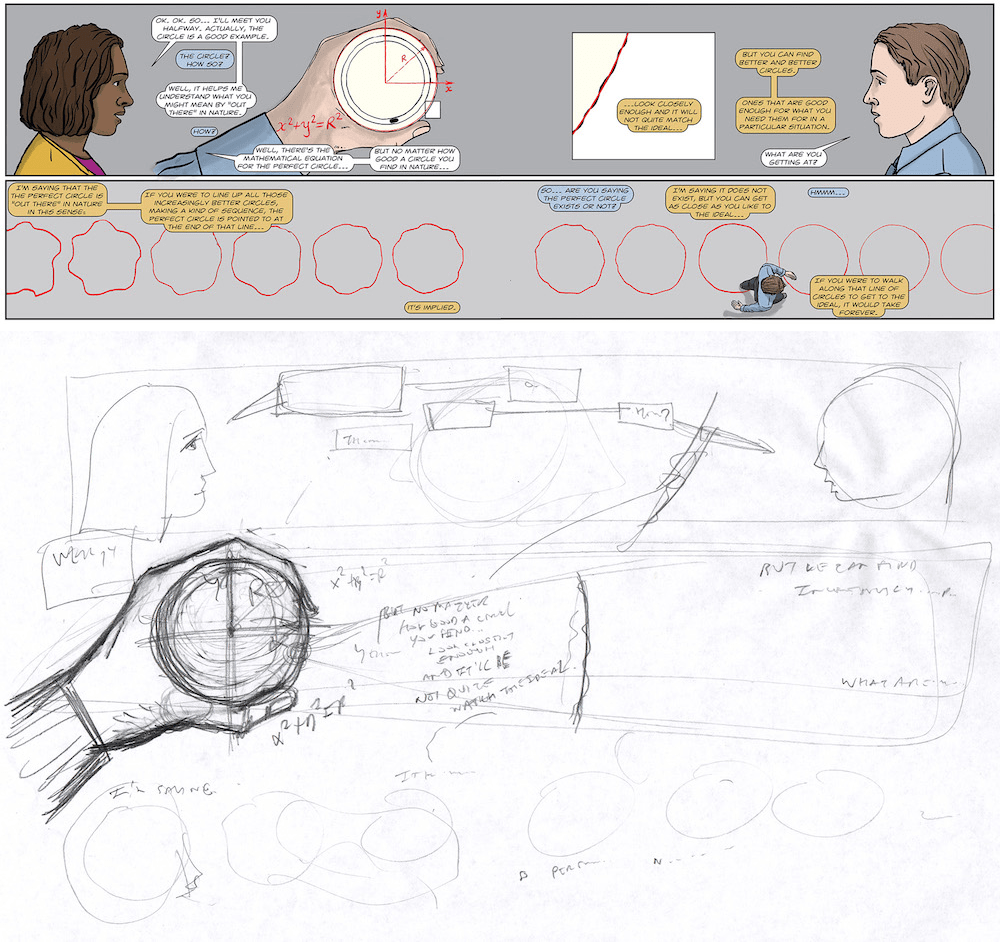

IRA FLATOW: And we have some of the working sketches for the book up on our web site, next to the finished panels. People can find that at sciencefriday.com/physics. But I wonder if that process of refining and revision in art is really all that different from the same process when we’re working on a new physics theory– refining, rewriting, finding the beauty in the equation.

[INTERPOSING VOICES]

CLIFFORD JOHNSON: Go ahead Janna.

JANNA LEVIN: No, I was just going to say I love that aspect of the book. I think that’s so important, exactly what you’re saying, Clifford, that a lot of science books are kind of coming down from the mountain– and again, no disrespect because they’re wonderful– but with the answers.

And really the process of discovery is very, very messy and very exciting. That’s half the thrill. And as Ira’s saying in these sketches, you see this kind of wonderful process of discovery and getting deeper and better and closer to some kind of representation that you’re really looking for.

IRA FLATOW: Did you set, Clifford, did you set out to do it that way or did you wind up saying this is the only way I could do it?

CLIFFORD JOHNSON: Actually, about, I want to say 18 years ago, I first had the core idea for the book, which was to have dialogue. So I really wanted dialogues to be upfront. I wanted it to be more that you’re being invited to be part of, or at least to witness, conversations about science, as opposed to having the news brought to you from on high, as it were. So that was the core idea.

And then, I thought it would be really engaging to maybe see who these people who were who having the conversation. And then later on I thought, hey, it would be fun to see where they’re having the conversation. And then gradually, over a number of years, those elements, those visual elements became more and more important to me.

And it wasn’t until about 2005-2006, when I realized, oh wait, I should just use narrative art for this. And then I realized, oh, this is a nonfiction graphic novel that I should just– I should just make this thing. And so, that was the beginning of the final journey of starting the drawing.

IRA FLATOW: Our number– 844-724-8255. You can also tweet us at scifri. Talking about the dialogues, conversations about the nature of the universe with Clifford V. Johnson. And also Janna Levin– tell us about your NOVA special.

JANNA LEVIN: It aired on Wednesday. It’s called Black Hole Apocalypse, but it’s now– you can stream it from the NOVA website, for the next few weeks. It was a real experiment in also visual representation.

And that’s a different situation, because unlike Clifford’s book, which I really admire, particularly because of the single authorship, drawing it himself– I mean, that just really has my admiration. This is a big collaboration. It’s a big team– a lot of people involved in the writing and the direction and the production. And a lot of scientists interviewed for it, and each giving their side. So it’s a completely– almost the opposite end of that kind of creative experience.

CLIFFORD JOHNSON: It’s great, though, I saw it. It’s wonderful.

JANNA LEVIN: Thanks. Thanks so much. I get to fly around in a spaceship. I mean, who doesn’t want to do that. I fall into a black hole. I mean, you know–

CLIFFORD JOHNSON: Yeah.

IRA FLATOW: Well let’s bring up black holes, because in the book, in the dialogues, it appears that the black hole, if we understand the black hole, we might be able to unite the two un-unitable parts of physics now, which [INAUDIBLE]– which is the [INAUDIBLE] grand unified theory, gravitation, and quantum physics.

Is that– is that– when you set out to write the book, is that a major theme you wanted to show, that we might be able to unite those conflicts there?

CLIFFORD JOHNSON: It wasn’t one of the main things I wanted to talk about, but it did come up a number of times, because black holes tend to draw you in, both physically and narratively, among other things.

And in the field of research of theoretical physics, trying to understand some of these questions, black holes have become central, because they lie at the cusp of the best we know about the classical understanding of space-time which is Einstein’s theory of general relativity, and quantum mechanics.

Somehow, black holes turn out to be this wonderful testbed for any new ideas you have about quantum gravity, how space and time work quantum mechanically, which is one of the big quests.

You have to test it against what black holes are telling you and how black holes behave. And sometimes, it either sinks or swims on how well it behaves in that context. So black holes have become this wonderful laboratory of ideas.

IRA FLATOW: Janna, you agree?

JANNA LEVIN: Yeah, absolutely. We talked a lot, in the show, about black holes– how nature actually makes them. Theoretically, they’re incredibly interesting, but for a long time even Einstein believed nature would protect us from their formation, that, that wouldn’t be possible.

And the fact that nature thought of a way to make black holes, which seems to involve killing off really big stars as a death state, is phenomenal. But what Clifford is saying is absolutely true, that almost more importantly, black holes are a fundamental landscape on which we can act out the most extreme scenarios that involve the clash between the physics on the small scales, quantum mechanics, and the physics on the largest scales, which is the curved space-time.

And it’s really only there, or maybe in the black hole, that we have a way of getting clues and evidence, even theoretically, by pushing the mathematics of what’s next.

IRA FLATOW: Because that’s where they meet, right?

JANNA LEVIN: Yes.

IRA FLATOW: They’re right there– both elements that are seemingly irreconcilable, are reconciled.

JANNA LEVIN: Well they’re not reconciled, but in our minds, yet.

IRA FLATOW: Right. But the black hole was reconciled.

JANNA LEVIN: Yes.

CLIFFORD JOHNSON: Indeed. And so, it goes back– of course, one of the most famous names in this field is Stephen Hawking, and it goes back somewhat to some of the work that was going on at the time, including Hawking’s work, but most famously Hawking radiation, which–

IRA FLATOW: I’m going to tell you to save that thought, because we have to take a break. It’s a good place to go back to– Hawking radiation. Clifford Johnson and Janna Levin. We’ll be right back after this break. Stay with us.

This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. We are talking about physics this hour, and especially about black holes. We’ll get into all kinds of cosmology, here. With me is Clifford Johnson, author of The Dialogue’s– Conversations About the Nature of the Universe. It’s a big comic book. It’s a graphic novel, as the new terminology would call it. It’s just wonderfully done.

CLIFFORD JOHNSON: Thank you.

IRA FLATOW: And also part about it, what I was really struck about, was you had panels in there that had no conversation. There was no dialogue. It’s like, this is where you think. You’re watching the characters just sitting and thinking about what they’ve just said.

CLIFFORD JOHNSON: Yes. I also like to celebrate silence as a breathing space, visually, in comics– I think is a really wonderful thing. There’s always the danger that people will just sort of skip through those bits and look for the speech bubbles.

But I hope that some people will appreciate that– what I’m trying to give you– time for yourself to think and maybe the characters are thinking, or maybe the whole story is sort of working up to this dialogue. And there’s these quiet parts that it’s nice to actually go through slowly, in anticipation of the conversation.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, because it’s good that it’s written, because we can look back on the panels and there are equations in there, some famous equations in there, that I’ve– have new– I’ve found new meaning in them from what you’ve written.

Let’s go to the phones. Let’s go to Martina, in Oakland. Hi there.

MARTINA: Hi there. Can you hear me OK?

IRA FLATOW: I can. Go right ahead.

MARTINA: Thank you. I wanted to– this is seemingly unrelated. I wanted to thank the author. I just took a first glance at your book, and I immediately noticed that your characters are multiethnic. And my daughter, who is black, often doesn’t see herself or find herself in books, and I’m so excited that she will find herself in this one.

It means a lot to parents like me, so thank you.

CLIFFORD JOHNSON: Oh thank you. I’m glad to hear that.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, there are– you look like you have tried to put as much as you can of diversity into the book.

CLIFFORD JOHNSON: Yeah, and it didn’t seem sort of like an add on or a forced thing that I was trying to do. It just– I was designing characters and I really just wanted to show ordinary people out there in the world having conversations about science, because that’s where science belongs– with everyone.

And so, it would have it would have been a big fail had I not ended up with a range of different kinds of people on the page.

IRA FLATOW: One of the scientists, in the book, makes the point that you can have a simple, elegant underlying theory, and yet, still have lots of solutions to the equations that define it, Janna. So it’s not so simple or elegant, if that’s true.

JANNA LEVIN: Yeah. This has happened in string theory where there’s a proliferation of solutions and what one sort of hopes for as a scientist is that there’s a prediction for one– for on being singled out.

And so, we find ourselves in this unusual position where there’s this theory, which may– may be the one that unifies quantum mechanics, and gravity, and explains the black hole, and explains Hawking evaporation, and explains so much, is not singling out a specific solution. And that leads us to ideas like the multiverse. Maybe there are many universes in which there all slightly different permutations of the laws of physics. We’re grappling with that.

IRA FLATOW: And people, in the book– the characters in the book are saying maybe we need new physics.

JANNA LEVIN: Or string theory is wrong and we need new physics– yeah.

IRA FLATOW: And does– and it gets to a question I ask a lot when I– because I can’t understand all the mathematics, and I can’t understand 12 dimensions or whatever, is maybe the math really doesn’t describe reality, even though it works.

JANNA LEVIN: I mean– yeah. It’s an interesting question, because mathematicians are way ahead of us in inventing mathematics that they don’t foresee will have application in physics. The mathematics that Einstein used existed beforehand, and he found an application for it by understanding it could represent curved space-time.

Is it possible that all the mathematics always has a representation in physical reality? I mean, these are profound questions. Or are simple things, like irrational numbers, simply not part of reality?

CLIFFORD JOHNSON: Yes. It is actually– that’s one of the stories starts out with that discussion, which is well do you actually– well, it comes up in the discussion, which is did we invent mathematics or did we discover it? And depending upon which position you take, it does say something about the whole business of research and theoretical physics.

These wonderful things we make up, sometimes they could just end up being wrong or maybe they’ll have applications we just haven’t thought of yet. String theory may turn out to be wrong for the things we started applying it for, but maybe it’ll have applications in some other piece of physics one day, and so on and so forth. It’s very interesting.

IRA FLATOW: Well when does– when does an idea, I mean, lose its validity, if we don’t have a test for it, like string theory. We can’t test– and then you talk about that in the book a little bit. And Janna, let me get–

JANNA LEVIN: Well, I think that, that’s actually something we just have to accept that our tests might not catch up with our ideas in a human lifespan. But that doesn’t mean that the ideas have failed.

When we prove that something can’t be proven, that’s a whole other level. That’s like good old proof that things can’t be proven. We’re nowhere near that. There is absolutely no proof that string theory can’t be proven. And I think that as long as it remains possible, we have to allow for the great ideas to come.

And maybe they won’t come in the next five-10 years, maybe they’ll come in 100. And that’s just something we have to accept.

CLIFFORD JOHNSON: It’s important to remember that physicists are really very pragmatic. And this goes back to the whole business of what side are you on– string theory or anti-string theory? Physicists are very pragmatic.

And the point is, is that string theory, right now, seems to be in best shape for doing what we think we’re trying to do with unifying, you know, quantum mechanics, and gravity, and things like that.

But if something better came along, you would see even the most die-hard string theorists would drop string theory in a flash and work on that other thing. It’s really that– we’re not really religiously wedded to string theory in the way that is often presented. It really is pragmatism. We’re just trying to find the tools that work best for describing nature, because we’re physicists.

IRA FLATOW: You know, and you get the impression because that– from reading the book, because there are so many different subjects and people brought up in the book, and we sort of lose track how many physicists are out there thinking on different ideas we never hear about.

And maybe one of those ideas will bubble up, so to speak, and become acceptable. But there are so many different ideas that they’re kicking about.

JANNA LEVIN: Well, what I think you’re striking on, which is something which is very important, and I’m not sure has as important a place in science today as it ought to, and that is risk taking.

And I really encourage young scientists not to be afraid of making mistakes or taking risks. And there is a real sort of aversion to that, professionally. And I think it’s very important to be willing to be wrong or you’re really not stretching enough or trying on great enough ideas.

IRA FLATOW: And one of the topics that you just touch on in the dialogues, which is now seeming to me as we follow physics on Science Friday, is the lack of the inclusion of entanglement enough in physics theory.

In other words, we now are talking more, we see more people talking about how entanglement is real. But we don’t see it enough in the equations or it’s just now entering into the mainstream. Am I reading that wrong, Clifford?

CLIFFORD JOHNSON: It’s actually becoming, in the last few years– that’s changing rapidly, in a very positive way.

I think there were many times, in various discussions going back decades, where we would touch on some of the more full-on aspects of quantum physics in our discussions of black holes and things like that. But we’d back away. And then, the conversations would come back later on, and we’d, again, sort of back off from the fully quantum description.

This time around, we’re revisiting a lot of these old questions about the nature of space-time and quantum physics and what have you with perhaps better tools and better intuition than we’ve ever had. And those tools include full on descriptions of things like entanglement from quantum theory, and so on and so forth.

To the point now, that there are toy models that people work on, where you actually discover space-time as a sort of approximation to an underlying reality which is much more quantum mechanical, which is much more about entanglement. So space-time emerges as a sort of derived object from an underlying quantum reality.

And those are the sorts of things we’re hoping we can build into a full theory of how the world works, eventually.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s go to the phones– 844-724-8255. Let’s go to Mark, in Lincolnshire, Illinois. Did I get that right, Mark?

MARK: Yes, you did. Thank you very much. Hi. Great show. I listen to it nearly every week whilst I’m traveling. I just go– I mean, both Clifford and Janna, really hit the point of it’s not coming, as Janna said, not coming down from the mountain with the answer. There’s a whole story behind it.

And I’d just like to give one recently, where my father is a permanent citizen in the UK, and he has come up with a– he’s been– was over here, in the US, for a while, and was down in North Carolina looking at a Museum of a sheet of mica. And on those sheets of mica there are tracks. And he worked for 50 years to prove that those tracks were particle tracks.

And eventually, one of the particle tracks he couldn’t explain, and he discovered out of that a new energy form, called quodon. And that’s now gone into– they looked– think they are now pushing that forward even further. And it could be the new– I’m not going to say superconductivity– it’s– called it hyperconductivity. But the story– back to what Janna was saying, it’s a story of 50 years of work and risk-taking as she was saying. So, absolutely right. Really well put. Great show, [INAUDIBLE]. Thank you.

IRA FLATOW: Thanks for the call.

JANNA LEVIN: Yeah. I really often like to emphasize that this is a kind of climbing Mt. Everest endeavor that a lot of scientists take this on for reasons that are hard to understand, and can take their entire lives. And not everyone makes the summit. And there are some amazing stories of success and failure along the way.

IRA FLATOW: But it’s not just the scientists, because somebody has to pay them. Somebody has to fund the research and make the choice, we are going to fund this.

JANNA LEVIN: Absolutely. And if you look at the LIGO story, in particular, the funders were crucial in ensuring that this succeed. And there were many opportunities along the way for them to turn away and let the project fizzle. And so, we also have to thank our country for supporting science and not forget that.

CLIFFORD JOHNSON: Yes.

IRA FLATOW: So going back to one of the main points I made before, because we’re running a little bit– we could talk about this forever, but– let’s talk about the 800 pound gorilla in the room, which is a black hole. A little heavier than that maybe.

Is the black hole going to be the Rosetta Stone for physics?

JANNA LEVIN: Yeah, I mean, I really feel that the black hole is the key to providing us evidence. It’s giving us clues all the time, and as we experiment, even just in pen and paper, on the surface of a black hole, it is nudging us ever closer to some revelation. And I think it may be. What do you think, Clifford? I don’t know.

CLIFFORD JOHNSON: Yeah, I think it, as I said before, it has this pull, both literally and metaphorically, which is interesting in that it’s showing– the concepts of black hole and the mathematics and physics of the black hole leads you to– shows up in so many different areas of theoretical physics, both directly and indirectly, and that’s really interesting to see.

I think there’s an interesting history story that’s going to be told about that. But it’s also instructive physically. You know, astrophysics is the obvious place. Now, a whole new way, because of colliding black holes giving us gravitational waves signals that we can detect, expanding astrophysics in a huge way.

But then, you come to questions of the quantum nature of space, et cetera, and again, black holes seem to be central there. But then, through things like string theory, you find that the properties of black holes, even abstract properties on the page, black holes in strange space-times, if you work out the mathematics, sometimes turn out to be powerful ways of recasting other kinds of physics, which you can actually dress up to look like the physics of black holes, for the sake of doing a useful calculation.

So black holes are becoming this sort of ubiquitous concept and even a toolbox for doing physics, so it is quite a remarkable idea.

IRA FLATOW: I’m Ira Flatow. This is Science Friday from PRI, Public Radio International. In case you’re just joining us, talking with Clifford Johnson, author of The Dialogues– Conversations About the Nature of the Universe. And we’re also talking with Janna Levin, who is– what? You got the NOVA special– is it the same title of your book– Black Hole Blues?

JANNA LEVIN: No, it’s Black Hole Apocalypse.

[LAUGHTER]

[INTERPOSING VOICES]

Yes, well it’s not a black hole utopia, is it? Black Hole Blues is actually so named because Ray Weiss, won the Nobel Prize for the LIGO discovery of the colliding black holes along with Kip Thorne and Barry Barish, that Clifford just mentioned, gave me the title, because he said to me, like a month before the discovery, if we don’t detect black holes, this whole thing’s a failure.

[LAUGHTER]

IRA FLATOW: Well and he was thinking of things we haven’t discovered yet. Is the whole idea of the theory of everything– is that gone? Is there still possible– that’s been talked about for decades.

JANNA LEVIN: Yeah, it’s not gone. It’s really still, in some sense, what Clifford’s referencing when we’re describing what the black hole can do for us. It can drive us towards that theory of everything. It will be interesting, if it turns out– so the theory of everything is supposed to unify the matter forces, which is electro weak and strong, currently, which we think can be unified, and gravity. Gravity is really the outlier.

Now it might be interesting, if, again, as Clifford said, it turns out that it’s only matter forces, and gravity is this illusion that emerges from the quantum phenomenon– that it’s just something that we see on large scales, but doesn’t actually fundamentally exist.

IRA FLATOW: Clifford, do you have a second act to The Dialogue? Is there another book?

CLIFFORD JOHNSON: I– the original book, as originally proposed, was about 400 pages long, so I cut out about enough for almost a second volume. I actually think it would be fun to revisit some of the same characters having other conversations.

But more in terms of the physics, which is really the starring character, I think I would probably delve even more into the quantum aspects, than perhaps I do in this book. I think there’s some wonderful things going on as we’ve already talked about in the context of understanding space-time and entanglements, and things like that, that deserve a visual treatment that they really haven’t been given.

And there’s something about the language of narrative sequential art, comics if you like, that lends itself to physics more than almost any other form. And I think this is just the beginning of what one might be able to do. So as an experiment, I’m curious to get going. It just– it takes a long time.

IRA FLATOW: I can say– I can tell. And it’s beautifully written, beautifully drawn, very well thought out, easy to read, makes you think, and a beautiful book. Great work.

CLIFFORD JOHNSON: Thank you. Thank you very much.

IRA FLATOW: Clifford Johnson, author of The Dialogues– Conversation About the Nature of the Universe. He’s also professor of physics at the University of Southern California and co-director of the LA Institute for Humanities there. We’ll have to talk about that someday.

CLIFFORD JOHNSON: Yeah, let’s.

IRA FLATOW: Janna Levin, author of Black Hole Blues. Her special on black holes out in NOVA this week. And she’s also a professor of physics and astronomy at Barnard. You can see her NOVA series. You can stream it. Good to see you again, Janna.

JANNA LEVIN: Great to see you.

Copyright © 2018 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Christopher Intagliata was Science Friday’s senior producer. He once served as a prop in an optical illusion and speaks passable Ira Flatowese.